"Every

work of art is fragrant of its time," says Laurence Binyon. The religion

of Vaishnavism and particularly, the Radha-Krishna cult provided Kangra

painters with inspiration while in Sansar Chand they found a patron who

honoured and encouraged them. It was in such happy circumstances that these

artists created a style which combines elegance with nervous grace. There is

delicacy and sensitivity in the line, combined with rare beauty of colour. For

almost forty years these artists were aglow with inspiration and they created

these memorable paintings which communicate spiritual concepts of the Krishna

cult so vividly. It is not a spiritual art in the Western Christian sense,

where spirit and body are regarded as two separate entities. It is not gloomy, cold

and forbidding, but is an art which is a happy blend of the sensuous and the

spiritual. The spirituality is not chilled by an asceticism which is disdainful

of female loveliness and the delights of love. In fact, its spirituality is

very much based on flesh and blood. It is an art which glorifies female beauty

and revels in the loveliness of the female form.

This

art is an interpretation of the religious creed of Vaishnavism, the religion of

love, which inspired the poetry of Keshav Das, Sur Das, and Bihari. No doubt,

the verses of these poets inspired whole cycles of painting in Rajasthan, but

the manner in which Khushala, the Kangra artist, matched his imagination with

the poet Bihari's is unique indeed. With what depth of feeling, and sincerity

he has painted the love poems of Bihari! As in the art of China and Japan,

there is a close association of poetry and painting in the art of Kangra. The

aim of the artist was to embody in the picture the emotion caused by reading

the poem. In this he achieved unique success, and in the process of translating

poetry into painting, he also evolved an art which has lyrical quality. This

explains the emotive power of these paintings, which are really love lyrics

translated into line and colour. In no other art does one see such a successful

and harmonious association of literary and plastic ideas.

The

aesthetics of an age grows out of its environment, physical, cultural,

spiritual, technological and economic. We have already mentioned the cultural

and spiritual background of Kangra painting in the religion and poetry of the

Vaishnavas. We will now explain the influence of physical environment on Kangra

art. 'I do not want to exaggerate the importance of climatic factors,' says

Herbert Read, 'but the fact remains that when-ever an ideological movement whether

merely stylistic or profoundly religious and spiritual is transplanted into a

region of different climatic and material conditions, that movement is

completely transformed. It adapts itself to the prevailing ethos that emanation

of the soil and the weather which is the characteristic spirit of a

community.'" This is what happened to Mughal styles of painting when they

reached the Punjab hills. Mughal painting had already achieved excellence in

portraiture and scenes of the zenana. The fluid line and delicate colouring of

some of the Mughal paintings is truly admirable. It is the religious paintings,

however, in which princes and emperors are shown in conversation with saints,

which are the most inspired products of the Mughal school, and have a rare

mystic quality which is the hall-mark of great art. Such paintings are,

however, few and the main preoccupations of the Mughal artists were durbar and

hunting scenes, and portraiture. It is only when the later Mughal style reached

the valley of Kangra and absorbed the elements of a new environment that it

blended beauty and lyrical quality with exquisite flow of line. Mughal

paintings were usually painted against the background of the drab and

monotonous plains of northern India. When the artists introduced the gently

undulating hills, rivulets and the characteristic vegetation of the Shivaliks,

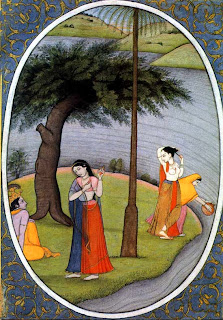

painting in the Kangra valley acquired grace and loveliness. In fact, it is the

passionate love of hill scenery which dominates Kangra painting and lends it

charm. The sophistication of the court, its dullness, and regimentation were

forgotten. And instead the atmosphere of the hill village, with its joy,

freedom, contact with nature, and serenity, makes its appearance. Take away the

hills, the rivers, and the groves of trees from these paintings, and see how

much they lose in beauty!

The

aesthetics of an age grows out of its environment, physical, cultural,

spiritual, technological and economic. We have already mentioned the cultural

and spiritual background of Kangra painting in the religion and poetry of the

Vaishnavas. We will now explain the influence of physical environment on Kangra

art. 'I do not want to exaggerate the importance of climatic factors,' says

Herbert Read, 'but the fact remains that when-ever an ideological movement whether

merely stylistic or profoundly religious and spiritual is transplanted into a

region of different climatic and material conditions, that movement is

completely transformed. It adapts itself to the prevailing ethos that emanation

of the soil and the weather which is the characteristic spirit of a

community.'" This is what happened to Mughal styles of painting when they

reached the Punjab hills. Mughal painting had already achieved excellence in

portraiture and scenes of the zenana. The fluid line and delicate colouring of

some of the Mughal paintings is truly admirable. It is the religious paintings,

however, in which princes and emperors are shown in conversation with saints,

which are the most inspired products of the Mughal school, and have a rare

mystic quality which is the hall-mark of great art. Such paintings are,

however, few and the main preoccupations of the Mughal artists were durbar and

hunting scenes, and portraiture. It is only when the later Mughal style reached

the valley of Kangra and absorbed the elements of a new environment that it

blended beauty and lyrical quality with exquisite flow of line. Mughal

paintings were usually painted against the background of the drab and

monotonous plains of northern India. When the artists introduced the gently

undulating hills, rivulets and the characteristic vegetation of the Shivaliks,

painting in the Kangra valley acquired grace and loveliness. In fact, it is the

passionate love of hill scenery which dominates Kangra painting and lends it

charm. The sophistication of the court, its dullness, and regimentation were

forgotten. And instead the atmosphere of the hill village, with its joy,

freedom, contact with nature, and serenity, makes its appearance. Take away the

hills, the rivers, and the groves of trees from these paintings, and see how

much they lose in beauty!

The

Kangra valley is undoubtedly one of the beauty spots of the world, and people

who are sensitive to beauty of nature, when they happen to visit it, come back

full of praise for it. On the one side is a snow-covered mountain range

towering to an altitude of 16,000 feet above sea-level. Below it is a green,

sloping valley, at an altitude ranging from 3,000 to 4,000 feet, strewn with

enormous lichen-stained boulders. Tropical mangoes and plantains jostle with

temperate cherries, crab apples, medlars and rambling roses. No scenery

presents such sublime and delightful contrasts. Carefully terraced fields,

irrigated by streams which descend from perennial snows, present a picture of

rural loveliness and repose which cannot be seen elsewhere in India. The

terraces sparkle like mosaics of mirrors when they are flooded with water in

the month of June. Then follows the velvet green paddy crop. Green is a

soothing colour but it is hard to match the rich shade of paddy plants which

shine like emeralds in the sun. Nowhere in the vegetable kingdom can we see

such an exquisite shade of green, so comforting and so pleasant. Spread all

over are homesteads of farmers, buried in groves of mangoes, bamboos,

plan-tains and kachnar. Unlike most hillmen, the people of Kangra are conscious

of the beauty of their land. In one of their folk songs, they thus pay homage

to their native hills:

Oh mother Dhauladhar, you have made Kangra a paradise.

Green, green hills, and deep, deep gorges with rivers flowing.

Lithe and handsome young men, and lovely women who speak so

gently.

Oh, my dear land of Kangra, you are unique.

If

common people could feel the beauty of the valley, sensitive artists could not

remain immune to it. In fact, they responded enthusiastically to the charm of

gentle hills and rolling valleys.

If

common people could feel the beauty of the valley, sensitive artists could not

remain immune to it. In fact, they responded enthusiastically to the charm of

gentle hills and rolling valleys.

It

is, however, surprising that though the artists were living and working in a

valley, where the snow-covered mountain range of the Dhauladhar is constantly

in sight, in none of the paintings do we find the snows painted. The Dhauladhar

is perhaps too domineering, cold and forbidding. That is why it seems the

artists preferred painting the gently undulating Shivalik hills among which

they lived.

The

Kangra artists were hereditary painters who worked in the quiet of their

cottages in the sylvan retreats of the Kangra valley. Sons and nephews were

usually accepted as pupils and they served the master artists by carefully

grinding mineral colours, a work requiring skill and patience. It is thus they

were initiated into the art and technique of painting. Life was simple, and the

Rajas provided foodgrains and a cow for milk to the artists. Whenever they

presented a beautiful painting to the Raja, they were handsomely rewarded. Thus

their economic needs were taken care of by their patrons, and they were free to

devote their entire time to painting. Miniature painting requires infinite

patience and care, and it is a type of art which could flourish only in an age

of leisure, under a benevolent feudalistic system. At the close of the

nineteenth century, art also languished because of the lack of patronage. Apart

from this, the inspiration was gone, and the generation of geniuses, who

painted the well-known masterpieces, had also passed away. Why, in particular

periods, certain countries reach a high level of creativeness, is one of the

unsolved riddles of history. The spell of creative enthusiasm which gripped the

Kangra valley for a century and then ebbed away likewise remains only partially

explained.

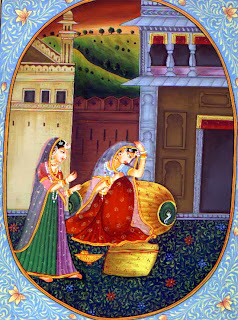

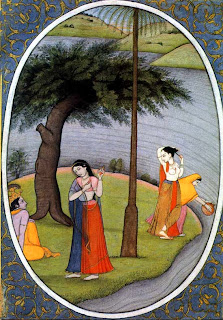

Here

is an art which celebrates life and love. And with what delicacy the ecstasies

of love are depicted! This art is truly a record of human joy. The eyes of

lovers meet and a world of feeling and tenderness is revealed in them. There

are chance encounters in the courtyard, and Radha who is keeping her secret

from the prying and inquisitive sakhis, conveys her message in the language

which the lovers alone mutually understand. Radha meets Krishna suddenly near

the entrance door of her house. While he looks at her with hungry eyes, she

stands veiled, with her face bent down, and she looks like a painted image, a

picture of innocence, swayed by the crosscurrents of youthful passion and

virgin modesty. We find her gazing at Krishna from the terrace, the windows and

balconies of her home. With what elegance the artist has depicted the

restlessness of love!

Here

is an art which celebrates life and love. And with what delicacy the ecstasies

of love are depicted! This art is truly a record of human joy. The eyes of

lovers meet and a world of feeling and tenderness is revealed in them. There

are chance encounters in the courtyard, and Radha who is keeping her secret

from the prying and inquisitive sakhis, conveys her message in the language

which the lovers alone mutually understand. Radha meets Krishna suddenly near

the entrance door of her house. While he looks at her with hungry eyes, she

stands veiled, with her face bent down, and she looks like a painted image, a

picture of innocence, swayed by the crosscurrents of youthful passion and

virgin modesty. We find her gazing at Krishna from the terrace, the windows and

balconies of her home. With what elegance the artist has depicted the

restlessness of love!

Clad

in a white sari, the lovely girl is cooking. The beauty of her face, and the

charm of her personality have brightened the kitchen.

Another

characteristic of these paintings is the manner in which dramatic relations and

expectancy are expressed through design, as well as expression, on the faces of

the lovers.

Others

are present, and, due to modesty, physical contact is not possible. She glances

at Krishna with loving eyes through her veil, and on some pretext she moves

away brushing her shadow with his shadow.

The

lovers are standing in the balconies of their houses facing each other. Their

fixed gaze has provided a rope on which their hearts travel fearlessly like

rope-dancers.

Demonstrates

the strength, as well as the weakness, of this form of art. While the delicate

profile of the Nayika is so fascinating, the full face of her companion is

positively repulsive. When these artists make an attempt to paint the full face

they fail.

Demonstrates

the strength, as well as the weakness, of this form of art. While the delicate

profile of the Nayika is so fascinating, the full face of her companion is

positively repulsive. When these artists make an attempt to paint the full face

they fail.

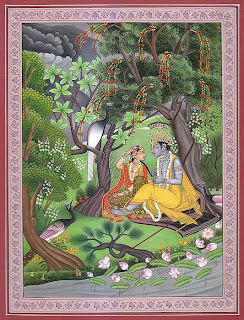

Clad

in white, the lady has gone into the moon-light to meet her lover. It is white

everywhere and hidden in it only the fragrance of the body enables her sakhi to

follow her. The white radiance of the moon and its pale silvery light has been

marvellously evoked by the artist.

The

artist has shown considerable skill in painting night scenes. The night is

pitch-dark and the lane is narrow. The lovers coming from opposite directions

brush against each other, and only the light touch of their bodies enables them

to recognize each other. How brilliantly the artist has painted the inky sky,

resplendent with stars!

Against

the background of a paddy field and her home stands the demure village beauty.

Wearing a fillet, and holding a stick, stands she of the slender waist, with

eyes downcast, unconscious of her innocent charm and beauty. A garland

decorates her round breasts.

Excepting

two, all the paintings of the Sat Sal are designed in an oval with an arabesque

in the border.

Apart

from forty paintings, out of which twenty-seven have been reproduced in this

book, there are about twenty drawings or unfinished paintings. This suggests

that the artist who had taken up the project of illustrating the seven hundred

verses of Bihari may have died, leaving his work unfinished. It seems that the

inscriptions on the back of the paintings were written later on. Out of the

paintings reproduced in this book hardly ten bear correct inscriptions. The

remainder have no inscriptions or have wrong ones, the situation shown in the

painting being entirely different from that described in the poem. Out of the

drawings ten are reproduced in this chapter.

The

Nayika sits under a leafless tree, immersed in grief, while her companions show

deep concern. The love-sick Nayika is sitting in the courtyard reclining

against a pillow. Her sakhi thus addresses her: "O deceitful girl! you

cannot conceal your feeling of love, even if you make a million efforts. Your

simulated indifference is itself disclosing that your heart is saturated with

love."

In the

Nayika is sitting behind the trellis and is looking at Krishna, who is standing

below. The poet says, "Although slanderous talk surrounds them, the lovers

do not give up the joy of exchanged glances." The anxiety of the Nayika to

have a glimpse of Krishna is great. The sakhis are standing on the stairs.

Commenting on the eagerness of the Nayika, one says to the other, "Look

hither a while, if you wish to see a marvel. Having torn the fence with her

fingers, she has been looking at him with unblinking eyes for a long

time."

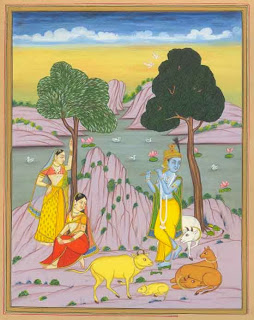

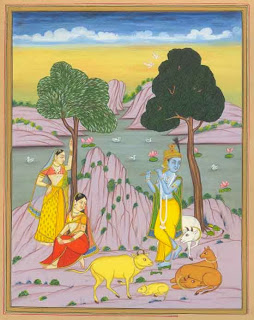

Both

the poetry and painting have a spirit of closeness to life, and in Radha,

Krishna and their friends and playmates, we find farmers and herdsmen of the

Kangra Valley, in their familiar surroundings of thatched cottages, nestling on

the spurs of mountains, against the background of lakes and rivers.

Though

it depicts the life of the rustics in the villages of the valley, Kangra

painting is not a folk art. It is essentially an aristocratic art, the patrons

of which were the Rajas who had fine sensibility and good taste. Thus, like the

best art of Europe, Kangra painting is the art of an elite.

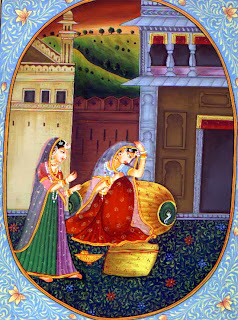

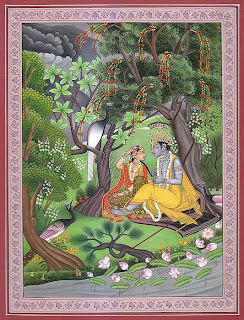

The

Gita Govinda is a forest idyll, and in its Kangra paintings, the drama of the

loves of Radha and Krishna is played in the forest, or along the river-bank. In

the paintings of the Bhagavata Purana, the incidents in the life of the boy

Krishna are depicted against the background of the forests of Vrindavana and

the river Yamuna. It is the trees of the forest, and the current of the river

which are most prominent in these paintings. On the other hand, in the

paintings of the Sat Sal-the background of architecture provides the setting

for the love drama of Radha and Krishna. It is against the background of

straight lines of walls, windows and balconies that the games of love are

carried on by Radha and Krishna, watched by the sakhis.

The

parallel straight lines and right angles create a compositional pattern of

restfulness and calm, illustrating Kafka's observation that 'closed areas are

more stable.' Here we find the beauty of geometry in harmony with the beauty of

the female form. Against the repose of the static architectural compositions,

we feel the restlessness of love. While the architectural setting has

precision, the human figures have a fluid grace matching the elegance of a

waterfall against the straight vertical lines of a mountain. With what gliding

grace lovely female forms flit across courtyards! And always there is a pair of

confidantes discussing the course of love of the divine couple. They are

unhappy and have an expression of serious concern on their faces, when there is

dissension or misunderstanding among the lovers, and they are never tired of

coaxing, cajoling, or giving advice. When the course of love runs smoothly,

they are unrestrainedly happy.

The

knitting together of form and colour into a coordinated harmony is the essential

of great art. In these Kangra paintings, form and colour are so blended that

the effect is musical. To achieve such a harmony, the artist made use of both

line and colour in these paintings. The line which he used is the musical,

rhythmical line, which expresses both movement and mass. The type of line which

Blake admired, and regarded as the golden rule of art as well as life, is this:

"The more distinct, sharp and wiry the bounding line, the more perfect the

work of art, and the less keen and sharp, the greater is the evidence of weak

imagination." And what a rhythm the dancing line creates, a pure limpid

harmony! That is why these pictures are so comforting and so soothing, like the

concertos of great Western composers of music such as Bach and Mozart. This

line was effectively supplemented by colours the blues, yellows, greens, and

reds, the pure colours of earth and minerals, which shine like jewels and have

not been dimmed by the passage of time. The combination of fluid line and

glowing colours ultimately produced an art which combines the beauty of figure

with dignity of pose, set against the calm of the hills.

The

knitting together of form and colour into a coordinated harmony is the essential

of great art. In these Kangra paintings, form and colour are so blended that

the effect is musical. To achieve such a harmony, the artist made use of both

line and colour in these paintings. The line which he used is the musical,

rhythmical line, which expresses both movement and mass. The type of line which

Blake admired, and regarded as the golden rule of art as well as life, is this:

"The more distinct, sharp and wiry the bounding line, the more perfect the

work of art, and the less keen and sharp, the greater is the evidence of weak

imagination." And what a rhythm the dancing line creates, a pure limpid

harmony! That is why these pictures are so comforting and so soothing, like the

concertos of great Western composers of music such as Bach and Mozart. This

line was effectively supplemented by colours the blues, yellows, greens, and

reds, the pure colours of earth and minerals, which shine like jewels and have

not been dimmed by the passage of time. The combination of fluid line and

glowing colours ultimately produced an art which combines the beauty of figure

with dignity of pose, set against the calm of the hills.

Writer Name: M.S. Randhawa

The

aesthetics of an age grows out of its environment, physical, cultural,

spiritual, technological and economic. We have already mentioned the cultural

and spiritual background of Kangra painting in the religion and poetry of the

Vaishnavas. We will now explain the influence of physical environment on Kangra

art. 'I do not want to exaggerate the importance of climatic factors,' says

Herbert Read, 'but the fact remains that when-ever an ideological movement whether

merely stylistic or profoundly religious and spiritual is transplanted into a

region of different climatic and material conditions, that movement is

completely transformed. It adapts itself to the prevailing ethos that emanation

of the soil and the weather which is the characteristic spirit of a

community.'" This is what happened to Mughal styles of painting when they

reached the Punjab hills. Mughal painting had already achieved excellence in

portraiture and scenes of the zenana. The fluid line and delicate colouring of

some of the Mughal paintings is truly admirable. It is the religious paintings,

however, in which princes and emperors are shown in conversation with saints,

which are the most inspired products of the Mughal school, and have a rare

mystic quality which is the hall-mark of great art. Such paintings are,

however, few and the main preoccupations of the Mughal artists were durbar and

hunting scenes, and portraiture. It is only when the later Mughal style reached

the valley of Kangra and absorbed the elements of a new environment that it

blended beauty and lyrical quality with exquisite flow of line. Mughal

paintings were usually painted against the background of the drab and

monotonous plains of northern India. When the artists introduced the gently

undulating hills, rivulets and the characteristic vegetation of the Shivaliks,

painting in the Kangra valley acquired grace and loveliness. In fact, it is the

passionate love of hill scenery which dominates Kangra painting and lends it

charm. The sophistication of the court, its dullness, and regimentation were

forgotten. And instead the atmosphere of the hill village, with its joy,

freedom, contact with nature, and serenity, makes its appearance. Take away the

hills, the rivers, and the groves of trees from these paintings, and see how

much they lose in beauty!

The

aesthetics of an age grows out of its environment, physical, cultural,

spiritual, technological and economic. We have already mentioned the cultural

and spiritual background of Kangra painting in the religion and poetry of the

Vaishnavas. We will now explain the influence of physical environment on Kangra

art. 'I do not want to exaggerate the importance of climatic factors,' says

Herbert Read, 'but the fact remains that when-ever an ideological movement whether

merely stylistic or profoundly religious and spiritual is transplanted into a

region of different climatic and material conditions, that movement is

completely transformed. It adapts itself to the prevailing ethos that emanation

of the soil and the weather which is the characteristic spirit of a

community.'" This is what happened to Mughal styles of painting when they

reached the Punjab hills. Mughal painting had already achieved excellence in

portraiture and scenes of the zenana. The fluid line and delicate colouring of

some of the Mughal paintings is truly admirable. It is the religious paintings,

however, in which princes and emperors are shown in conversation with saints,

which are the most inspired products of the Mughal school, and have a rare

mystic quality which is the hall-mark of great art. Such paintings are,

however, few and the main preoccupations of the Mughal artists were durbar and

hunting scenes, and portraiture. It is only when the later Mughal style reached

the valley of Kangra and absorbed the elements of a new environment that it

blended beauty and lyrical quality with exquisite flow of line. Mughal

paintings were usually painted against the background of the drab and

monotonous plains of northern India. When the artists introduced the gently

undulating hills, rivulets and the characteristic vegetation of the Shivaliks,

painting in the Kangra valley acquired grace and loveliness. In fact, it is the

passionate love of hill scenery which dominates Kangra painting and lends it

charm. The sophistication of the court, its dullness, and regimentation were

forgotten. And instead the atmosphere of the hill village, with its joy,

freedom, contact with nature, and serenity, makes its appearance. Take away the

hills, the rivers, and the groves of trees from these paintings, and see how

much they lose in beauty!  If

common people could feel the beauty of the valley, sensitive artists could not

remain immune to it. In fact, they responded enthusiastically to the charm of

gentle hills and rolling valleys.

If

common people could feel the beauty of the valley, sensitive artists could not

remain immune to it. In fact, they responded enthusiastically to the charm of

gentle hills and rolling valleys.  Here

is an art which celebrates life and love. And with what delicacy the ecstasies

of love are depicted! This art is truly a record of human joy. The eyes of

lovers meet and a world of feeling and tenderness is revealed in them. There

are chance encounters in the courtyard, and Radha who is keeping her secret

from the prying and inquisitive sakhis, conveys her message in the language

which the lovers alone mutually understand. Radha meets Krishna suddenly near

the entrance door of her house. While he looks at her with hungry eyes, she

stands veiled, with her face bent down, and she looks like a painted image, a

picture of innocence, swayed by the crosscurrents of youthful passion and

virgin modesty. We find her gazing at Krishna from the terrace, the windows and

balconies of her home. With what elegance the artist has depicted the

restlessness of love!

Here

is an art which celebrates life and love. And with what delicacy the ecstasies

of love are depicted! This art is truly a record of human joy. The eyes of

lovers meet and a world of feeling and tenderness is revealed in them. There

are chance encounters in the courtyard, and Radha who is keeping her secret

from the prying and inquisitive sakhis, conveys her message in the language

which the lovers alone mutually understand. Radha meets Krishna suddenly near

the entrance door of her house. While he looks at her with hungry eyes, she

stands veiled, with her face bent down, and she looks like a painted image, a

picture of innocence, swayed by the crosscurrents of youthful passion and

virgin modesty. We find her gazing at Krishna from the terrace, the windows and

balconies of her home. With what elegance the artist has depicted the

restlessness of love!  Demonstrates

the strength, as well as the weakness, of this form of art. While the delicate

profile of the Nayika is so fascinating, the full face of her companion is

positively repulsive. When these artists make an attempt to paint the full face

they fail.

Demonstrates

the strength, as well as the weakness, of this form of art. While the delicate

profile of the Nayika is so fascinating, the full face of her companion is

positively repulsive. When these artists make an attempt to paint the full face

they fail.  The

knitting together of form and colour into a coordinated harmony is the essential

of great art. In these Kangra paintings, form and colour are so blended that

the effect is musical. To achieve such a harmony, the artist made use of both

line and colour in these paintings. The line which he used is the musical,

rhythmical line, which expresses both movement and mass. The type of line which

Blake admired, and regarded as the golden rule of art as well as life, is this:

"The more distinct, sharp and wiry the bounding line, the more perfect the

work of art, and the less keen and sharp, the greater is the evidence of weak

imagination." And what a rhythm the dancing line creates, a pure limpid

harmony! That is why these pictures are so comforting and so soothing, like the

concertos of great Western composers of music such as Bach and Mozart. This

line was effectively supplemented by colours the blues, yellows, greens, and

reds, the pure colours of earth and minerals, which shine like jewels and have

not been dimmed by the passage of time. The combination of fluid line and

glowing colours ultimately produced an art which combines the beauty of figure

with dignity of pose, set against the calm of the hills.

The

knitting together of form and colour into a coordinated harmony is the essential

of great art. In these Kangra paintings, form and colour are so blended that

the effect is musical. To achieve such a harmony, the artist made use of both

line and colour in these paintings. The line which he used is the musical,

rhythmical line, which expresses both movement and mass. The type of line which

Blake admired, and regarded as the golden rule of art as well as life, is this:

"The more distinct, sharp and wiry the bounding line, the more perfect the

work of art, and the less keen and sharp, the greater is the evidence of weak

imagination." And what a rhythm the dancing line creates, a pure limpid

harmony! That is why these pictures are so comforting and so soothing, like the

concertos of great Western composers of music such as Bach and Mozart. This

line was effectively supplemented by colours the blues, yellows, greens, and

reds, the pure colours of earth and minerals, which shine like jewels and have

not been dimmed by the passage of time. The combination of fluid line and

glowing colours ultimately produced an art which combines the beauty of figure

with dignity of pose, set against the calm of the hills.

0 Response to "Kangra Paintings Of The Sat Sai "

Post a Comment