Three Faces of Cosmos

The

cosmos revolved around Mount Mandara. On its peak sat Shiva in serene

meditation, unconcerned with the world, transcending samsara.

In

his hand was Brahma's skull, serving as his drinking-bowl. With it he

confronted the world, the body and the mind, with its mortality. He was

Kapalin, the skull-bearer.

Shiva

was glad to be out of the cycle of life.

Brahma

was not.

"If every creature on earth renounces the

world like Shiva, the universe will cease to exist. This must be stopped. But

how? " Brahma turned to Vishnu, the cosmic savior, for help.

"We

must get him a wife," replied Vishnu, "One who will bring him back

into the ways of the world.

"For

the survival of society the quest for moksha, spiritual liberation, must be

supplemented with the fulfillment of dharma, material duty.

"The

path of restraint, yoga must be balanced with the delights of pleasure, bhoga.

Together, Shiva with his consort will generate the middle path between

participation, bhukti and renunciation, mukti."

Brahma

agreed.

Suddenly

the antagonism between Brahma and Shiva became clear to the gods Brahma was

rajasic, active and energetic while Shiva was tamasic, passive and inert. What

Brahma created srishthi, Shiva destroyed, samhara what Shiva destroyed, Brahma

recreated. The two justified each other's existence. While Brahma was

passionately involved in the creation of the world, Shiva was equally

dispassionate about it, preferring to transcend its wiles and become an

ascetic. Now that he had, it was time to recreate the cosmic tension by

seducing him back into the ways of the world.

Suddenly

the antagonism between Brahma and Shiva became clear to the gods Brahma was

rajasic, active and energetic while Shiva was tamasic, passive and inert. What

Brahma created srishthi, Shiva destroyed, samhara what Shiva destroyed, Brahma

recreated. The two justified each other's existence. While Brahma was

passionately involved in the creation of the world, Shiva was equally

dispassionate about it, preferring to transcend its wiles and become an

ascetic. Now that he had, it was time to recreate the cosmic tension by

seducing him back into the ways of the world.

Between

Shiva and Brahma stood Vishnu, the cosmic savior, always ensuring survival of

the prevailing order, sthithi. He was totally sattvic, constantly trying to

create a balance between the aggressiveness of the creator and the aggressiveness

of the destroyer.

"But

where will we find a woman who will match Shiva in spirit and strength?"

wondered Brahma. "I have already found one the mother-goddess

herself," said Vishnu.

"Yes,

yes. Who better than her! She is the personification of prakriti, embodiment of

Nature's elements and energies. But will she agree?"

"She

already has ... look, she has already taken birth in the house of the prajapati

Daksha as his youngest daughter, Sati."

Daksha's Daughter

Daksha,

the prajapati, was the master of civilization, samaj. He formulated the rules

of society and ensured the survival of the traditional order. His daughters were

wives of the gods and their children had gone on to populate the whole world.

Daksha,

the prajapati, was the master of civilization, samaj. He formulated the rules

of society and ensured the survival of the traditional order. His daughters were

wives of the gods and their children had gone on to populate the whole world.

His

youngest child, Sati, was something very special, a manifestation of the

mother-goddess herself. She would make the perfect wife for Shiva, thought

Vishnu. Brahma agreed.

But

there was one problem Daksha himself.

Prajapati

Daksha never liked Shiva. Shiva was Ekavratya, an unorthodox hermit, who lived

by his own rules, not always acceptable to traditional society. He refused to

conform to the ways of the world. As guardian of civilization, Daksha found

that subversive.

"Shiva

wanders in cremation grounds with a rowdy bunch of renegades consuming

intoxicants that are forbidden in decent society. He sings and dances wherever

he wants to, with little heed to decorum and protocol. He has no home, no

possessions, no family, no vocation; he is a no good drifter, ritually impure,

unsuitable for any of my daughters, especially Sati," he said.

These

were of course excuses. There was a very simple reason why Daksha couldn't

stand Shiva: Shiva refused to indulge Daksha's ego.

Daksha

made the laws, defined codes of conduct, formulated the rules of society. He

naturally considered himself to be someone special, someone more important than

others. He expected everyone to bow before him. Shiva refused. He refused to

indulge any social rules that promoted pomposity in the name of respect.

Above

the bowed heads of the gods, Daksha saw Shiva. "He does not respect me;

nor does he disrespect me. It is as if I don't exist, that I don't

matter!" thought Daksha.

Daksha Curses the Moon

Once,

Shiva saved the moon. By doing so, he incurred Daksha's wrath.

Once,

Shiva saved the moon. By doing so, he incurred Daksha's wrath.

Chandra,

the moon-god, had married twenty seven of Daksha's daughters the nakshatras,

lunar asterisms. But he preferred only one of them, the charming Rohini. He

ignored the rest, angering Daksha who cursed him, "May your radiant body,

of which you are so proud, wither away and disappear."

As

the curse took effect, Chandra became weak and dim. With each passing day his

lustre waned. Terrified, he went to the gods seeking a cure. But there was none

forthcoming. Vishnu suggested, "Go to Shiva. He is Somnath, keeper of the

sacred herb soma that might cure you."

Sure

enough Vaidyanath, the supreme physician, helped restore his lustre.

But

in time Daksha's accursed disease returned, once again gnawing into Chandra's

flesh. The moon-god ran to Shiva for help and again sought the magical soma.

Even this cure was followed by a relapse. This went on for some time curse

followed by cure followed by curse. Daksha's terrible malady wouldn't go away.

Finally Shiva said, "Come and stay within the locks of my hair. Here you

will find all the soma you need. Each time the disease troubles you, you can

rejuvenate yourself with my grace."

Shiva's

blessing went against Daksha's curse. While Daksha caused the moon to wane,

Shiva by placing the moon on his head helped it to wax again. Shiva, the

saviour of the moon, came to be known as Chandrashekhara. Thanks to him,

moonlight came to be filled with the magic of soma and the moon came to be

known as Soma.

Daksha

considered Shiva's action an insult to his authority. He definitely did not

want this maverick for a son-in-law.

Daksha

considered Shiva's action an insult to his authority. He definitely did not

want this maverick for a son-in-law.

But

the matter was out of his hands. Sati was already in love with Shiva and had

made up her mind to marry him.

Shiva and Sati

"How

can I marry her?" cried Shiva, when Vishnu made the suggestion. "I

have renounced the world," he said. But he could not ignore the intensity

of Sati's love for him.

The

prajapati's daughter had abandoned the pleasures of society to be with him. She

lived like a hermit, alone, deep in the forest, surviving on fruits and roots,

performing terrible austerities, tapas, demanding an audience with the

hermit-lord.

"Why

do you want to marry me?" Shiva asked her.

"Because

you are incomplete without me and I am incomplete without you."

"But

I have nothing to offer you?"

"I

do not ask for anything, but you."

"I

have neither property nor a lineage, kula, nor do I desire any."

"I

accept you for what you are, not for what you have."

"I

only observe society; I do not participate in it."

"I

would like to observe it with you."

Sati's

determination impressed Shiva. He accepted her as his wife.

Brahma

and Vishnu rejoiced. The circle of life was complete as Shiva became yet

another cog in the wheel of existence.

Brahma

and Vishnu rejoiced. The circle of life was complete as Shiva became yet

another cog in the wheel of existence.

Only

Daksha was unhappy.

Daksha's Great Sacrifice

Sati

walked out of Daksha's palace. She followed Shiva wherever he went: over lonely

hills, across desolate plains and dense forests, through cremation grounds. In

Shiva's company she did not miss her father or his home or his society.

Shiva

at first ignored Sati. He barely acknowledged her presence. Sati didn't mind.

She followed him selflessly, content to be by his side. Her fortitude and

patience, her serene determination to be his consort, her giving nature and

radiant personality everything about her pleased Shiva. He fell in love.

Daksha

meanwhile organized a great yagna.

Everyone

was invited except Shiva.

"I

think it is an oversight. Let's go anyway," said Sati.

"No

Sati, don't be an uninvited guest."

Sati Kills Herself

"I

will go to my father's house, with or without you, whether you like it or

not," said Sati firmly.

"I

will go to my father's house, with or without you, whether you like it or

not," said Sati firmly.

Dressed

in her finest robes with a garland of lotuses round her neck, Shiva's

headstrong wife went to Daksha's yagna. She walked right into the sacrificial

hall. Around the sacred fire sat all the gods, the sages, deities from every

plane of existence. None rose to greet her. To her surprise, even her father

did not seem particularly pleased to see her.

"You

weren't invited. Why did you come? Have you had enough of your vagabond

husband?" Daksha asked. His words hit Sati like poisoned barbs. The

assembled gods and sages chose to ignore Daksha's remarks. Unlike them, Sati

stood up for Shiva. "My husband is no vagabond. He is a yogi, aware of the

ways of the cosmos."

Surprised

by his daughter's retort, Daksha said, "If he is such a wise man, how come

he does not know the basic rules of society. Look at the way he lives, the

clothes he wears, the company he keeps."

"Society

is an artificial creation of man. My lord is one with Nature, he is lord of the

plants, lord of the beasts."

"Society

is an artificial creation of man. My lord is one with Nature, he is lord of the

plants, lord of the beasts."

"Lord

of the beasts! He is a beast himself: no home, no family, no decency, no decorum.

I am ashamed to introduce him as my daughter's husband." The gods laughed.

Sati wept.

Suddenly

it all became clear; Sati realized that the sacrifice was an elaborate ritual

aimed at insulting her lord. The humiliation was too much to bear. Death seemed

a better alternative to the shame.

Sati

sat on the ground, her mind fixed on Shiva. She controlled her breath and

stoked her inner fire, prana-agni, until it consumed her.

The

fire she created is the dreaded Jwala-mukhi that is now found in Himachal Pradesh.

Shiva loses his Temper

News

of Sati's death shocked Shiva. Then came the pain.

Shiva

experienced the pangs of separation viraha, the anguish of loneliness. From

that suffering, dukkha, came anger, krodha. With the anger came the monsters of

fever: the germs that inflame the body and fill it with purulent fluids. Shiva

became Jvareshvara, lord of fevers. His indignation contorted his features and

turned him into the savage Virupaksha, the malignant-eyed.

Shiva

experienced the pangs of separation viraha, the anguish of loneliness. From

that suffering, dukkha, came anger, krodha. With the anger came the monsters of

fever: the germs that inflame the body and fill it with purulent fluids. Shiva

became Jvareshvara, lord of fevers. His indignation contorted his features and

turned him into the savage Virupaksha, the malignant-eyed.

Shiva

plucked out his hair and lashed it on the ground to create the grim Virabhadra

and the fierce Bhadrakali. "Go ravish the sacrifice violate the fire,

poison the waters, pollute the air and kill the gods. They deprived me of Sati,

let them be deprived of their lives," ordered Shiva.

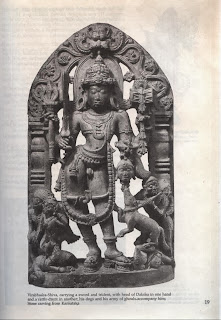

Virabhadra

picked up his trident and summoned an army, a cackling horde of ghosts,

goblins, ghouls, genii, monsters, demons, dragons, freaks, fiends and spirits the

ganas of Shiva. They marched towards Daksha's sacrificial halls cheered by the

shrill cries of Bhadrakali.

Evil

omens had begun to appear at Daksha's palace. Vultures circled above the

sacrificial altar, wolves howled.

Fear

arose in the very heart of the cosmos.

Destruction of the Sacrifice

A

hundred thousand rabid dogs rushed into Daksha's precinct carrying on their

backs the monsters of fever. These fiends leapt on the gods and struck them

with such fury that they all began to convulse and vomit blood.

Then

with a virulent war-cry Virabhadra and his savage entourage descended on the

scene. They wrecked the place: sacred vessels were kicked, tapestries were

ripped and pavilions burnt.

As

the gods took flight, the demons seized and massacred them all... Bhadrakali

drank their blood.

The

sage Bhrigu used his magical powers and tried to conjure up spirits who would

save the

sacrifice. But the spirits refused to emerge when they heard

Bhadrakali howl. Those that did were dismembered by Shiva's gams.

Finally

Bhadrakali dragged Daksha by his feet towards the fire-altar. Virabhadra raised

his axe and beheaded the prajapati. The severed head was tossed into the

flames.

Then,

Virabhadra laughed and Bhadrakali danced. She used the heads of the gods as

beads for her garland while he decorated his body with their entrails. The

ganas joined in the gory revelry. The sacrificial hall was now claimed by

Shiva. He became known as Hara, the ravisher.

With

that, Shiva's fury subsided. Only the sorrow remained.

Shiva forgives Daksha

Shiva

walked into Daksha's sacrificial hall and was confronted with the aftermath of

the bloodbath a feast for wolves, vultures and vampires. He was filled with

pity, karuna.

The

survivors of the carnage fell at his feet and begged for mercy. He smiled.

Instantly a fragrant breeze swept across the scene. The fevers subsided. The

dead gods arose as if waking from a deep slumber. Their wounds had healed, the

broken bones had been mended, the missing limbs restored.

Shiva

found Daksha's headless body and brought it back to life, replacing his head

with that of a goat.

Shiva

then gave him the city of Bhogya, "This is a city of uninhibited pleasure.

I created it for Sati. Here I indulged in every pleasure imaginable and became

a bhogi. But now Sati is no more. I have no use for Bhogya. I gift it to

you."

Daksha

was overwhelmed by Shiva's generosity. The goat headed prajapati began to sing

Shiva's praises. "You are Shankar, the benevolent one, a kind god,"

he said. Daksha completed his sacrifice. This time he gave Shiva his rightful

share. Shiva ceased being a rejected god, an outsider. He was accepted, adored,

held in awe. He became part of the celestial pantheon.

Only

Sati was dead.

Sati's Corpse is Destroyed

Shiva

picked up Sati's lifeless body and walked out of the sacrificial hall. He could

not bring himself to cremate it. The body was all that he had to remind him of

his beloved. He refused to part with it.

Shiva

picked up Sati's lifeless body and walked out of the sacrificial hall. He could

not bring himself to cremate it. The body was all that he had to remind him of

his beloved. He refused to part with it.

Distraught,

he wandered across the cosmos with Sati's corpse in his arms, tears rolling

down his cheeks. His ganas followed him silently, not knowing how to console

their lord. His mournful cry rent the galaxies and stunned the gods. "This

must stop," said Brahma, "Otherwise the whole cosmos will be

submerged by Shiva's agony."

Vishnu

raised his finger to spin his mighty discus, sudarshan chakra, and let it fly.

Its sharp edges ripped Sati's corpse into 108 pieces. These fell in different

parts of Jambudvipa, the rose apple continent of India, and became

shaktipithas, the shrines of Sati.

With

the body gone, there was nothing left to remind Shiva of Sati, except memories.

And memories fade.

Sati

had taught Shiva all about pleasure, Kama. Her departure had taught him about

anger, krodha. Together Kama-krodha trap man in samsara.

Shiva

had had enough of life. He isolated himself in the icy caves of the Himalayas.

He became a recluse once more.

The

mother-goddess, embodiment of all matter, is never stable. She is constantly in

a state of flux. Her death was just a transformation; Sati would return in

another form. The gods knew that. Shiva did too.

Writer Name:- Devdutt Pattanaik

Read Also:

Suddenly

the antagonism between Brahma and Shiva became clear to the gods Brahma was

rajasic, active and energetic while Shiva was tamasic, passive and inert. What

Brahma created srishthi, Shiva destroyed, samhara what Shiva destroyed, Brahma

recreated. The two justified each other's existence. While Brahma was

passionately involved in the creation of the world, Shiva was equally

dispassionate about it, preferring to transcend its wiles and become an

ascetic. Now that he had, it was time to recreate the cosmic tension by

seducing him back into the ways of the world.

Suddenly

the antagonism between Brahma and Shiva became clear to the gods Brahma was

rajasic, active and energetic while Shiva was tamasic, passive and inert. What

Brahma created srishthi, Shiva destroyed, samhara what Shiva destroyed, Brahma

recreated. The two justified each other's existence. While Brahma was

passionately involved in the creation of the world, Shiva was equally

dispassionate about it, preferring to transcend its wiles and become an

ascetic. Now that he had, it was time to recreate the cosmic tension by

seducing him back into the ways of the world.  Daksha,

the prajapati, was the master of civilization, samaj. He formulated the rules

of society and ensured the survival of the traditional order. His daughters were

wives of the gods and their children had gone on to populate the whole world.

Daksha,

the prajapati, was the master of civilization, samaj. He formulated the rules

of society and ensured the survival of the traditional order. His daughters were

wives of the gods and their children had gone on to populate the whole world.  Daksha

considered Shiva's action an insult to his authority. He definitely did not

want this maverick for a son-in-law.

Daksha

considered Shiva's action an insult to his authority. He definitely did not

want this maverick for a son-in-law.  Brahma

and Vishnu rejoiced. The circle of life was complete as Shiva became yet

another cog in the wheel of existence.

Brahma

and Vishnu rejoiced. The circle of life was complete as Shiva became yet

another cog in the wheel of existence.  "I

will go to my father's house, with or without you, whether you like it or

not," said Sati firmly.

"I

will go to my father's house, with or without you, whether you like it or

not," said Sati firmly.  "Society

is an artificial creation of man. My lord is one with Nature, he is lord of the

plants, lord of the beasts."

"Society

is an artificial creation of man. My lord is one with Nature, he is lord of the

plants, lord of the beasts."  Shiva

experienced the pangs of separation viraha, the anguish of loneliness. From

that suffering, dukkha, came anger, krodha. With the anger came the monsters of

fever: the germs that inflame the body and fill it with purulent fluids. Shiva

became Jvareshvara, lord of fevers. His indignation contorted his features and

turned him into the savage Virupaksha, the malignant-eyed.

Shiva

experienced the pangs of separation viraha, the anguish of loneliness. From

that suffering, dukkha, came anger, krodha. With the anger came the monsters of

fever: the germs that inflame the body and fill it with purulent fluids. Shiva

became Jvareshvara, lord of fevers. His indignation contorted his features and

turned him into the savage Virupaksha, the malignant-eyed.  Shiva

picked up Sati's lifeless body and walked out of the sacrificial hall. He could

not bring himself to cremate it. The body was all that he had to remind him of

his beloved. He refused to part with it.

Shiva

picked up Sati's lifeless body and walked out of the sacrificial hall. He could

not bring himself to cremate it. The body was all that he had to remind him of

his beloved. He refused to part with it.

0 Response to "Marriage of Shiva "

Post a Comment