It

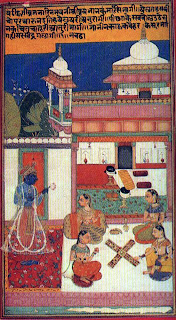

is just a late version of an early story repeated. Kushana sculpture in the

Yamuna-Ganga doab is the indigenous type, with only an occasional flash of

foreign influence, while the Kushana art in the Gandhara region imbibes more

from the West, though both these schools were patronised in the same empire and

almost by the same kings. Similarly, under the Mughal empire, art in the hills

and the desert, that continued the early tradition in sequestered spots,

undisturbed by Mughal magnificence, developed the Indian traditions untainted,

while contemporary Mughal art at court imbibed quite a bit of the Persian

tradition, though under the catholic spirit of Akbar and the liberal

connoisseurship of Jehangir, the art flowered into a peculiarly charming new

school having an essentially Indian flavour with a strong Persian bias. The

Hindu spirit of religious fervour and dedication is best seen in the series of

Rajasthani and Pahari miniatures illustrating the sports of baby Krishna, the

episodes from Rama's life, the complex epic of the Mahabharata, the loves of

Nala and Damayanti, the triumph of Chandi or Durga, the musical modes the main

and subsidiary ragas and raginis, personified in picturesque fashion, the

emotions, the longing of the separated wife, Proshitabhartrika, the pride of

the wronged wife, Khandita, the eager expectant wife, Vasakasajjika, the damsel

hurrying to the place of tryst, Abhisarika, the shy coy bride, Mugdha, and so

forth. The Baramasa scenes with magnificent representations of the rains and

spring, the former dark with rain-laden clouds and the latter bright with

gardens and woods lit up with flowers in bloom, are all typical of the genius

and outlook of the Rajasthani painter, who continued the tradition of the past,

pleasing himself in this presentation of a maze of themes already executed by

numerous predecessors but nevertheless still as fresh as ever in their charm

and inviting depiction over and over again. It was very rarely that the artist

individualized himself and put his stamp by inscribing his name. The themes

survived. The glory of depiction is there but the artist effaced himself. As

Anandavardhana would put it for literature, the same Mayas of the greatest

poets like Valmiki, Vyasa and Kalidasa could yet be repeated by other poets

drawing from the same sweet source-garden and portrayed to appear as fresh and

lovely and glorious as in the originals by an artistic turn given individually

by every great poet who utilized them. The Rajasthani and Pahari artists

exactly followed this procedure and produced some of the loveliest creations

with the brush.

It

is just a late version of an early story repeated. Kushana sculpture in the

Yamuna-Ganga doab is the indigenous type, with only an occasional flash of

foreign influence, while the Kushana art in the Gandhara region imbibes more

from the West, though both these schools were patronised in the same empire and

almost by the same kings. Similarly, under the Mughal empire, art in the hills

and the desert, that continued the early tradition in sequestered spots,

undisturbed by Mughal magnificence, developed the Indian traditions untainted,

while contemporary Mughal art at court imbibed quite a bit of the Persian

tradition, though under the catholic spirit of Akbar and the liberal

connoisseurship of Jehangir, the art flowered into a peculiarly charming new

school having an essentially Indian flavour with a strong Persian bias. The

Hindu spirit of religious fervour and dedication is best seen in the series of

Rajasthani and Pahari miniatures illustrating the sports of baby Krishna, the

episodes from Rama's life, the complex epic of the Mahabharata, the loves of

Nala and Damayanti, the triumph of Chandi or Durga, the musical modes the main

and subsidiary ragas and raginis, personified in picturesque fashion, the

emotions, the longing of the separated wife, Proshitabhartrika, the pride of

the wronged wife, Khandita, the eager expectant wife, Vasakasajjika, the damsel

hurrying to the place of tryst, Abhisarika, the shy coy bride, Mugdha, and so

forth. The Baramasa scenes with magnificent representations of the rains and

spring, the former dark with rain-laden clouds and the latter bright with

gardens and woods lit up with flowers in bloom, are all typical of the genius

and outlook of the Rajasthani painter, who continued the tradition of the past,

pleasing himself in this presentation of a maze of themes already executed by

numerous predecessors but nevertheless still as fresh as ever in their charm

and inviting depiction over and over again. It was very rarely that the artist

individualized himself and put his stamp by inscribing his name. The themes

survived. The glory of depiction is there but the artist effaced himself. As

Anandavardhana would put it for literature, the same Mayas of the greatest

poets like Valmiki, Vyasa and Kalidasa could yet be repeated by other poets

drawing from the same sweet source-garden and portrayed to appear as fresh and

lovely and glorious as in the originals by an artistic turn given individually

by every great poet who utilized them. The Rajasthani and Pahari artists

exactly followed this procedure and produced some of the loveliest creations

with the brush.

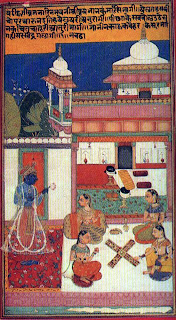

The

Rajasthani School of Art is a natural outcome of a long sequence of art

tradition. The miniatures that comprise the Rajasthani School, found in such

profusion in several art galleries of India and the world, did not, strangely

enough, originate as miniatures. There are several large-size drawings and

cartoons which show that this was primarily a mural art. In the palaces at

Jaipur and Udaipur, there are wall paintings which show how wonderfully the

painter of this school produced large murals. The Rasalila and the love of

Radha and Krishna form a happy theme. Mention in the Naradapancharatra,

ascribed to the sixteenth century, of the palace of Siva at Kailasa, decorated

with pictures of Krishnalila, indicates, as Coomaraswamy rightly observes, that

such pictures "were commonly to be seen at the gates and on the walls of

lovely palaces".

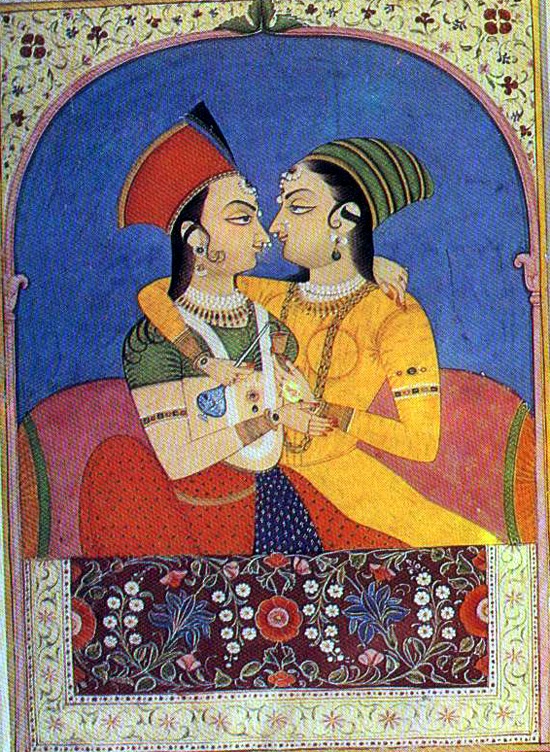

With

a long heredity, Rajasthani painting continued a tradition and the conservative

fashion remained practically unaffected except for a slight inevitable Mughal

influence at a later stage. But the Mughal paintings which were essentially

rich in Persian traditions soon imbibed the charm of Indian tradition. While

the Mughal paintings were aristocratic, individualistic, strong in their

character of portraiture, being fostered and appreciated only by royalty and

noblemen at court, as they were reflections of their personal glory and vanity,

the Rajput paintings were more in tune with the throbbing life around, simple,

with a direct appeal to the peasant and the common folk, sublime in theme,

universal in appeal, deeply religious and mystic, true interpreters of phases

of nature in her moods in spring and in rain and emotions in man, bird and

beast with a universal love for both the animate and the inanimate, the deer,

the dove, the peacock, the monkey, cows and calves, trees and creepers, lovely

brooks, shady bowers, moisture-laden clouds showering rain-drops with circling

cranes, the melodies personified attracting even the beasts and reptiles to listen

to the songs, or the lovers in separation or in union; in short, themes whose

appeal goes direct to the heart of peasant and nobleman alike. As has already

been remarked, Rajasthani painting and painting from the hilly region, Pahari,

closely knit by affinities that make them almost a single major school, show

the least trace of foreign admixture, while Mughal art betrays it most.

It

is just a late version of an early story repeated. Kushana sculpture in the

Yamuna-Ganga doab is the indigenous type, with only an occasional flash of

foreign influence, while the Kushana art in the Gandhara region imbibes more

from the West, though both these schools were patronised in the same empire and

almost by the same kings. Similarly, under the Mughal empire, art in the hills

and the desert, that continued the early tradition in sequestered spots,

undisturbed by Mughal magnificence, developed the Indian traditions untainted,

while contemporary Mughal art at court imbibed quite a bit of the Persian

tradition, though under the catholic spirit of Akbar and the liberal

connoisseurship of Jehangir, the art flowered into a peculiarly charming new

school having an essentially Indian flavour with a strong Persian bias. The

Hindu spirit of religious fervour and dedication is best seen in the series of

Rajasthani and Pahari miniatures illustrating the sports of baby Krishna, the

episodes from Rama's life, the complex epic of the Mahabharata, the loves of

Nala and Damayanti, the triumph of Chandi or Durga, the musical modes the main

and subsidiary ragas and raginis, personified in picturesque fashion, the

emotions, the longing of the separated wife, Proshitabhartrika, the pride of

the wronged wife, Khandita, the eager expectant wife, Vasakasajjika, the damsel

hurrying to the place of tryst, Abhisarika, the shy coy bride, Mugdha, and so

forth. The Baramasa scenes with magnificent representations of the rains and

spring, the former dark with rain-laden clouds and the latter bright with

gardens and woods lit up with flowers in bloom, are all typical of the genius

and outlook of the Rajasthani painter, who continued the tradition of the past,

pleasing himself in this presentation of a maze of themes already executed by

numerous predecessors but nevertheless still as fresh as ever in their charm

and inviting depiction over and over again. It was very rarely that the artist

individualized himself and put his stamp by inscribing his name. The themes

survived. The glory of depiction is there but the artist effaced himself. As

Anandavardhana would put it for literature, the same Mayas of the greatest

poets like Valmiki, Vyasa and Kalidasa could yet be repeated by other poets

drawing from the same sweet source-garden and portrayed to appear as fresh and

lovely and glorious as in the originals by an artistic turn given individually

by every great poet who utilized them. The Rajasthani and Pahari artists

exactly followed this procedure and produced some of the loveliest creations

with the brush.

It

is just a late version of an early story repeated. Kushana sculpture in the

Yamuna-Ganga doab is the indigenous type, with only an occasional flash of

foreign influence, while the Kushana art in the Gandhara region imbibes more

from the West, though both these schools were patronised in the same empire and

almost by the same kings. Similarly, under the Mughal empire, art in the hills

and the desert, that continued the early tradition in sequestered spots,

undisturbed by Mughal magnificence, developed the Indian traditions untainted,

while contemporary Mughal art at court imbibed quite a bit of the Persian

tradition, though under the catholic spirit of Akbar and the liberal

connoisseurship of Jehangir, the art flowered into a peculiarly charming new

school having an essentially Indian flavour with a strong Persian bias. The

Hindu spirit of religious fervour and dedication is best seen in the series of

Rajasthani and Pahari miniatures illustrating the sports of baby Krishna, the

episodes from Rama's life, the complex epic of the Mahabharata, the loves of

Nala and Damayanti, the triumph of Chandi or Durga, the musical modes the main

and subsidiary ragas and raginis, personified in picturesque fashion, the

emotions, the longing of the separated wife, Proshitabhartrika, the pride of

the wronged wife, Khandita, the eager expectant wife, Vasakasajjika, the damsel

hurrying to the place of tryst, Abhisarika, the shy coy bride, Mugdha, and so

forth. The Baramasa scenes with magnificent representations of the rains and

spring, the former dark with rain-laden clouds and the latter bright with

gardens and woods lit up with flowers in bloom, are all typical of the genius

and outlook of the Rajasthani painter, who continued the tradition of the past,

pleasing himself in this presentation of a maze of themes already executed by

numerous predecessors but nevertheless still as fresh as ever in their charm

and inviting depiction over and over again. It was very rarely that the artist

individualized himself and put his stamp by inscribing his name. The themes

survived. The glory of depiction is there but the artist effaced himself. As

Anandavardhana would put it for literature, the same Mayas of the greatest

poets like Valmiki, Vyasa and Kalidasa could yet be repeated by other poets

drawing from the same sweet source-garden and portrayed to appear as fresh and

lovely and glorious as in the originals by an artistic turn given individually

by every great poet who utilized them. The Rajasthani and Pahari artists

exactly followed this procedure and produced some of the loveliest creations

with the brush.

Mughal

art, on the other hand, being individualistic, glorified particular themes,

specified aristocracy, peeped into the inner revelry of the harem, the

magnificence of the court, the delightful wild bouts, depicted elephant and

camel fights that appealed to the emperor, scenes of hunting, toilet, dress and

decoration of coquettish damsels; and the very spirit of emulation in the court

and the patronage of the emperors and the nobles drew out the stamp of the

personality of each artist, which accounts for the signed examples of painting

so profusely met with in the Mughal series.

The

Rajput rulers from Delhi, Mahoba, Ajmer and other places driven from their

strongholds during Mohammedan inroads, but who would not easily yield, found

resorts in the fastnesses of the comparatively neglected and to the Mohammedan

invader unimpressive Pahari hills and the desert regions of Rajasthan. With

their strong conservative views, hatred for everything foreign, and love and

reverence for hoary traditions they encouraged the continuance of the age-old

tradition of the art of painting on the walls, the old and beloved themes of

Krishna, the lord of love, Rama, the righteous and mighty king, noblest friend

and worthy foe and to his sweetheart most beloved, and a thousand other scenes

of emotion and nature sublimated. In the Pahari hills, the artist conceived not

a Rama or a Krishna clad in a form of great antiquity unknown and elusive to

him, but these gods were to him almost his companions on earth living and

moving exactly like those around him. It is this simple true-to-life type of

delineation that makes the examples of this school such a valuable

treasure-house for a study of the culture and civilization of the area during

the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.

The

various sub-schools of the Rajasthani School can be distinguished by their

peculiar characteristics such as the Mewar, Bundi, Jaipur, Bikaner and Jodhpur with

close affinities to the Central Indian Mandu (Malwa) School, which in turn owes

much to the Jain School of Gujarat. The Mewar School presents an early

untainted phase of Rajasthani mode unlike schools like Bikaner and Bundi that

absorbed Mughal influence. The pointed nose, large eyes and angular features of

figures, the general arrangement of browns and reds, and the wavy skyline in

the Mewar paintings recall influence from Gujarat manuscripts and from the very

early Rajasthani School of which the illustrations of Chaurapanchasika from the

N.C. Mehta collection are an excellent example. The Kishengarh School with

peculiarly long and mango-shaped oblique like Radha and Krishna is another

distinct school from the Rajasthan area. A peculiarly religious and almost

repetitive school is noticed from Nathadvara.

The

Pahari branch has its most graceful paintings in the Kangra, Guler, Chamba,

Nurpur, Garhwal and Jammu Schools and a strong folk element is seen in the Kulu

and Basohli Schools. This was a period of great renaissance of

vernacular literature when the influence of Kabir, Vidyapati, Umapati,

Chandidas, Tulsidas, Kesavadasa and even late writers like Bihari Lal and

Jaswant Singh had probably a greater hold than the more difficult and not so

easily accessible Sanskrit poets. Thus, the Ramayana of Tulsidas and the

Rasikapriya of Kesavadasa had probably a greater appeal and are actually the

source of the themes of this unsophisticated sweet utterance of folk-art, a

prakrita vernacular art to be distinguished from a classical samskrita art that

went in handy with classical Sanskrit literature of an earlier period.

Writer Name: C. Sivaramamurti

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Rajasthani and Pahari"

Post a Comment