Many

diverse trends were at work towards the end of the Vedic period. Gods which had

begun as simple representations of aspects of nature began to acquire

increasingly elaborate mythologies which personalized or anthropomorphized

them. At the same time, each of the gods was considered to encompass certain

activities of others and the divisions between them became blurred.

So

while many claimed to be creators or to exercise dominion over the universe,

none really emerged as supreme lord. One of the great preoccupations of the

Brahmanic age, or the period in which early Hinduism evolved roughly 900-550

B.C., was the search for the identity of the Supreme Being or universal spirit

which suffused all creation and all the other gods. There was much speculation about

the hierarchy and about whether one of the Vedic gods shod occupy the supreme

position and whether a new deity, Brahma, should be considered a manifestation

of o of the old gods or whether he was truly a new figure.

This

whole controversy was complicated by a further factor through the course of the

Vedic age a perhaps because of the greatly co fused hierarchy the power of the

priests, Brahmins, grew stronger and their essential function, the performance

of sacrifice, developed accordingly. In the Brahmanic age the situation

developed so far that sacrifice itself became the object of religious ritual,

for sacrifice represented not so much reverence to the gods as the creation of

powers which ensured the continuance of the universal cycles of time, which in

turn regulated the existence of the gods within the universe and their death

and rebirth.

According

to beliefs evolved during the Brahmanic period, universal time is a never

ending cycle of both creation and destruction, each complete cycle, being

represented by one hundred years in the life of Brahma. At the end of this

period the entire universe, Brahma himself, gods, sages, demons, humans,

animals and matter are dissolved in the Great Cataclysm, Mahapralaya. This is

followed by one hundred years of chaos, after which another Brahma is born and

the cycle begins anew. Within this system are many divisions and sub-cycles.

The most important of these is the Kalpa, one mere day in the life of Brahma

hut equivalent to 4,320 million years on earth. When Brahma wakes, the three

worlds (heavens, middle and lower regions) are created, and when he sleeps they

are reduced to chaos; all beings who have not obtained liberation are judged

and must prepare for rebirth according to their deserts when Brahma wakes on the new day. The Kalpa is divided

into one thousand Great Ages (Mahayugas), and each of these is further divided

into four ages or Yugas, called Krita, Treta, Dwapara and Kali.

The

Kritayuga is a golden age lasting 1,728,000 years, in which Dharma, god of

justice and duty, is said to walk on four legs. People are contented, healthy

and virtuous and worship one god, who is white.

The

Tretayuga, which lasts 1,296,000 years, is a less happy age in which virtue falls

short by one-quarter and in which Dharma is three legged. In general people

follow their duty, though they sometimes act from ulterior motives and are

quarrelsome. Brahmins are more numerous than wrongdoers, and the deity is red

in color.

In

the Dwaparayuga virtue is only half present and Dharma stands on only two legs.

During this age, which lasts for 864,000 years, the deity is yellow and

discontent, lying and quarrels abound. Nevertheless many tread the right path

and Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaisyas are careful to perform their duties.

The

Kaliyuga, or age of degeneration, is the one through which we are now passing.

Dharma is one legged and helpless, and all but one quarter of virtue has

vanished. In this age, lasting 432,000 years, during which the deity is black,

the majority of men are Sudras, or slaves. They are wicked, quarrelsome and

beggar like and they are unlucky because they deserve no luck. They value what

is degraded, eat voraciously and indiscriminately, and live in cities filled

with thieves. They are dominated by their womenfolk, who are shallow, garrulous

and lascivious, bearing too many children. They are oppressed by their kings

and by the ravages of nature, famines and wars. Their miseries can only end

with the coming of Kalki, the destroyer.

Destruction

is preceded by the most terrible portents. After a drought lasting one hundred

years, seven suns appear in the skies and drink up all the remaining water.

Fire, swept by the wind, consumes the earth and then the underworld. Clouds

looking like elephants garlanded with lightning then appear and, bursting

suddenly, release rain that falls continuously for twelve years, sub-merging

the whole world. Then Brahma, contained within a lotus floating on the waters,

absorbs the winds and goes to sleep, until the time comes for his awakening and

renewed creation. During this time gods and mortals are temporarily reabsorbed

into Brahman, the universal spirit. The creation to come will consist of a

redeployment of the same elements. Geographically, the mythical world seems to

change little. Our earth is shaped like a wheel and is the innermost of seven

concentric continents. In the centre of the world is Mount Meru, whose summit,

84,000 leagues high, is the site of Brahma's heaven, which is encircled by the

River Ganges and surrounded by the cities of Indra and other deities. The

foothills of Mount Meru are the home of benevolent spirits such as Gandharvas,

while the valleys are peopled by the demons. The whole world is supported by

the hood of the great serpent Shesha, who is sometimes himself coiled upon the

back of a tortoise floating on the primal waters or the world is supported by

four elephants or is held up by four giants, who cause earthquakes by shifting

their burden from one shoulder to the other.

At

the beginning of each cycle of creation the waters of the cataclysmic flood

cover the universe. There are many myths to explain the sequence of the new

creation. One of the most favored Vedic versions relates that the golden cosmic

egg, symbol of fire, was floating on the waters for a thousand years. At the

end of this period the egg burst open to reveal the Lord of the Universe, who

took the form of the first, eternal man, whose soul is identical with that of

the universal spirit and who, because he was the first to destroy all sins by

fire, was called Purusha. Though he had been entirely alone, communing with

himself for so long, when he emerged from the egg and cast his eyes about him

on the empty waters he felt afraid and this is why men feel afraid when they

are alone. But he comforted himself with the thought that as he was the only

being in the universe, he need feel no fear. On the other hand, he felt no

delight and this is why no one feels delight when alone. Then he felt desire for

another, and so divided himself into two, one half male and the other female

but then he felt himself to be disunited, so he joined with his other half,

Amvika or Viraj, who thus became his wife and bore offspring, mankind.

Thereafter Purusha and Viraj assumed the forms of pairs of cattle, horses,

asses, goats, sheep and all other creatures’ right down to ants, and each pair

produced offspring.

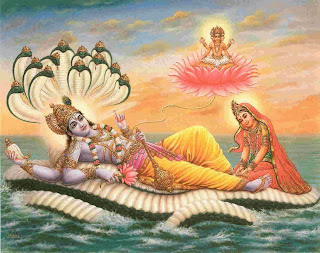

Another

one of these myths states that the creator was Narayana, who in some versions

appears to be an aspect of Brahma and in others an aspect of Vishnu. Narayana

lay for long ages on the primeval waters, Nara, floating on a banyan leaf while

sucking his toe a position symbolizing eternity. After this self communion, the

universe was formed by his will to create. Speech was born from his mouth, the

Vedas from the humors of his body, amrita from his tongue the very firmament

rose from his nose, heaven and the sun from the pupils of his eyes, places of

pilgrimage from his ears, clouds and rain from his hair, flashes of lightning

from his beard, rocks from his nails, mountains from his bones.

An

early myth, which originated about the time when sacrifice, and in particular

human sacrifice, attained great importance, was perpetuated with some

modification into modern times. This myth dispenses with the primal waters and

thus is intermediate between myths which take the great cataclysm into account

and those earlier ones which, without explanations, state that lndra, or

Varuna, or Indra, Agni and the Maruts created the universe (though it should be

noted that these early creations also appear to be more rearrangements of

existing matter than creations ex nihilo). According to this, the gods

performed a sacrifice with Purusha, the universal spirit which took the form of

a giant and was the first man. Spring was the butter of this sacrifice, summer

was its fuel, and autumn was its accompanying offering. From Purusha's head

rose the sky, from his navel the air, and from his feet the earth. From his

mind sprang the moon, from his eye the sun, from his ears the four quarters,

from his mouth Indra and Agni, and from his breath Vayu. The four castes, whose

symbolic colors are related to the colors of the four deities of the Yugas,

also sprang from Purusha: the Brahmins from his mouth, the Kshatriyas from his

arms, the Vaisyas from his thighs, and the Sudras from his feet.

The

myth was later adapted to Brahma, who was substituted for Purusha after

becoming established as the one universal spirit. In this way Brahma too,

though originally a philosophical, abstract conception the world spirit,

identification with which was the key to salvation or release became a

personalized deity. In later times Brahma was regarded as the fount and

justification of caste.

The

later myths all refer in some way to Brahma as creator. Thus one relates that

the lord of the universe brooded over the cosmic egg as it lay on the surface

of the ocean for a thousand years. As he lay there in self-communion a lotus,

bright as a thousand suns, rose from his navel and spread until it seemed as if

it could contain the whole world. From this lotus sprang Brahma, self-created,

but imbued with the powers of the lord of the universe. He set about his work

of creation but he was not omniscient, and made several mistakes. At his first

attempt he created ignorance, and threw her away but she survived and became

Night and from her is-sued the Beings of Darkness. Brahma had still not

succeeded in creating anything else, and these creatures in their hunger made

to devour him. He defended himself, appealing to them not to eat their own

father. But some of them would not listen to this appeal and wanted to eat him

any-way; these became the rakshasas, enemies of the human race, while their

less bloodthirsty brothers be-came the yakshas, who are sometimes hostile but

mostly friendly. Brahma learnt from this experience, and thereafter he created

a series of immortal beings and celestials. He also created the asuras from his

hip, the earth from his feet, and all the other components of the world from

other parts of his body.

Yet

another version ends the story differently. According to this, Brahma became

discouraged with his failures and created four sages or Mullis to carry out the

work for him. These sages were, however, less interested in the task of

creation that in the worship of Vasudeva (the universal spirit, later a name of

Krishna). Brahma became very angry at seeing the sages engaged in austerities

instead of fulfilling the purpose for which they had been created, and from his

anger sprang forth Itudra, who proceeded with and completed the work.

The

version of creation given in the Laws of Manu composed in the second century

A.D. combines many elements from the myths already discussed, but it introduces

a new feature Manu is a human being, a sage, who survives the destruction of

one Mahayuga (Great Age) and lives to play a leading part in the creation of

the next. This creation myth, imparted by Manu himself, hinges on the notion

which became current in the Brahmanic period that sages, strengthened by

knowledge and austerities, could acquire powers superior to those of the gods

themselves, for they could become absorbed into the universal world spirit.

Mann recounts that the self existent spirit felt desire (this is at times

personified as Kama, god of de. sire, who thus becomes the creative force). He

wished to create all the living things from his own body, so he first created

the waters, Nara, and threw a seed into them. From the seed grew a golden egg,

bright as the sun. The self-existent spirit, who became known as Narayana after

Nara, first dwelling place, developed with': the egg as Brahma, sometimes also

called Purusha, the Male. After a year's contemplation in the egg, Brahma

divided his body into two parts, one half male and the other female. Within the

female part he implanted Viraj (a male), and Viraj in turn created Manu, who

then created the world. Sometimes each age is said to have its own Mann, and it

is not clear whether all the Manus are really one. The following elaboration of

the myth suggests that the selfsame Manu existed in at least two ages.

According to the sage Markandeya, Manu, who was a great rishi or sage, himself

escaped destruction in the general cataclysm at the end of the last age.

Manu

had performed ten thousand years of austerities and had become equal to Brahma

himself in glory. As he was meditating one day beside a stream a fish spoke to

him from the water and besought his protection against another fish, which was

chasing it. Manu took the fish and put it into a jar. But the fish grew too big

for the jar, and asked to be taken to the Ganges. It outgrew the Ganges, and

Mann had to take it to the ocean. There at last the fish was content and

revealed to Mann that it was none other than Brahma himself. It further warned

Mann of the approaching destruction of the world by flood, and instructed him

to build an ark and to place in it the seven rishis and the seeds of everything

recognized by the Brahmins.

When

Manu had done this the deluge began and gradually submerged everything but the

ark which, tossed upon the surface of the waters, was drawn along by cables

attached to the horns of the fish, until it came to rest upon the highest peak

of the Himalayas, where Mann moored it to a tree. After many years the flood waters

began to recede, and Mann and his ark slowly descended into the valleys, where

the sage took up the work of creation for the next age.

After

worshipping the fish and engaging in austerities, Mann per-formed a sacrifice

in which he offered up milk, clarified butter, curds and whey. After a year

these offerings grew into a beautiful woman, who came to Manu and told him that

she was his daughter and advised him that with her help at a sacrifice he would

become rich in children and cattle and would obtain any blessing he desired. So

Manu did as she instructed and they performed many austerities in due time Mann

begot the human race and received many other blessings.

As

Indian philosophy became more detached from worldly preoccupations and came to

regard life with its series of incarnations as a source of misery, its

influence affected the creation myth. Typical of this pessimistic school of

thought is the story of Prajapati, or Brahma Prajapati, who himself was created

by mind. When Prajapati arose from the primordial waters he looked about him

and wept. From the tears that he wiped away rose the air from the tears that

fell into the waters arose the earth and those tears which he wiped up-wards

became the sky. Then, by casting off the shells of his body, Prajapati created

in turn the asuras, and darkness humans, and moon light the seasons, and

twilight the gods, and day and finally, death.

Yama

and his twin sister Yami are said to be the first man and woman. They were the

children of Vivasvat, the rising sun, and Saranyu, daughter of Tvashtri. At the

entreaty of Yami, they founded the human race, despite Yama's doubts as to

whether Varuna and Mitra really intended that they should be husband and wife.

When the human race had been established Yama became its pathfinder he was the

first to explore the hidden regions and discovered the road which became known

as the 'path of the fathers' this was the route which led the dead to heaven

Yama, having discovered it, not only became the first man to die but also

became established as King of the Dead.

At

first, like Yama, the dead had to walk along this route, but later the path of

the fathers (Manes or Pitris) was presided over by Agni, for when the dead were

cremated his fire distinguished between the good and the evil in them. The

ashes that remained on earth represented all that was evil and imperfect, while

the fire carried aloft, intact, the skin and limbs of the deceased. There,

brilliant like the gods and borne on wings or in a chariot, the purified soul

rejoined its glorified body and was greeted by the forefathers, who lived a

life of festivity in the kingdom of Yama. The afterlife was thus passed in a

delectable abode, and was perfect in every way all desires were fulfilled here,

in the presence of the gods, and eternal time was spent in the pursuit of

pleasure. Sometimes the abode of the gods was distinguished from that of the

fathers, the kingdom of Yama but the paths to both heavens were smoothed by

Again, their earthly entrances being the sacrificial fire and the funeral pyre.

Writer – Veronica Ions

Read Also:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Developments of the Brahmanic Age "

Post a Comment