Not

all the dead were permitted to remain in Yama's heaven. As a form of Mitra, and

associated with Varuna, Yama was a judge of the dead, known as Dharmaraja.

Dharma, truth or righteousness, by which Yama judged mortals who approached his

heaven, was a development of Varuna's rta, the inscrutable law. As Varuna

formerly bound the guilty with their sins against rta, so Yatna consigned the

wicked or unbelievers either to annihilation or to a realm of darkness called

Put. He was assisted in the task of judgment by Varuna, who sat with him

beneath a tree in the land of the fathers. Like a shepherd, Yama played his

flute and drank soma with the other gods. As the dead approached him he gave

the faithful draughts of the soma, thereby making them immortal. He was helped

in this task by his messengers, a pigeon and an owl, as well as two brindled

watch dogs, each with four eyes. In later times his assistant was said to be

Chitragupta, and he had other 'court recorders'.

At

first the emphasis was on the pleasures of Yama's heaven, a realm of light

where life had no sorrows, nature was sweet and the air full of laughter and

celestial music. The splendors of Yama's assembly house, built by Tvashtri from

burnished gold, were equal to those of the sun. There Yama, as Pitripati (king

of the fathers), was waited upon by servants who measured out the life span of

mortals, and was surrounded and worshipped by rishis and Pitris, clad in white

and decked with golden ornaments. The assembly house was filled with sweet

sounds, perfumes and brilliant flowers.

Yama's

heaven was not without rivals, and in particular it was challenged by the

splendors and delights of the heavens of Varuna and Indra. Varuna in his heaven

was no longer judge of the dead, as he had been when seated beside Yama; he was

already lord of the ocean. The heaven, which was constructed within the sea by

Tvashtri or Visvakarma, had walls and arches of pure white, surrounded by

celestial trees made of brilliant jewels which always bore blossom and fruit

birds sang everywhere. In the white assembly house Varuna sat enthroned with

his queen, both decked with jewels, ornaments of gold, and flowers. They were

attended by the minor deities the Adityas, the Nagas (serpents), the Daityas

and Danavas (ocean demons), the spirits of the rivers, seas and other waters,

and the personified forms of the cardinal points and the mountains.

Yama's

heaven was not without rivals, and in particular it was challenged by the

splendors and delights of the heavens of Varuna and Indra. Varuna in his heaven

was no longer judge of the dead, as he had been when seated beside Yama; he was

already lord of the ocean. The heaven, which was constructed within the sea by

Tvashtri or Visvakarma, had walls and arches of pure white, surrounded by

celestial trees made of brilliant jewels which always bore blossom and fruit

birds sang everywhere. In the white assembly house Varuna sat enthroned with

his queen, both decked with jewels, ornaments of gold, and flowers. They were

attended by the minor deities the Adityas, the Nagas (serpents), the Daityas

and Danavas (ocean demons), the spirits of the rivers, seas and other waters,

and the personified forms of the cardinal points and the mountains.

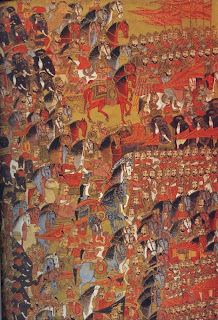

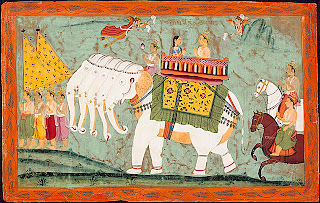

Indra's

heaven, also built by Tvashtri, was called Swarga and was situated on Mount

Meru, but could be moved anywhere like a chariot. Like the other heavens it was

adorned with celestial trees and filled with birdsong and the scent of flowers.

Indra enthroned in glory in the assembly house, wearing white robes, garlanded

with flowers and wearing gleaming bracelets and his crown. He was accompanied

by his queen, and attended by the Maruts, by the major gods and by sages and

saints, whole pure souls without sin were resplendent as fire. This concept of

lndra’s heaven is the one still held today. In it there is no sorrow, suffering

or fear for it is inhabited by the spirits of prosperity, religion, joy, faith

and intelligence. Also in lndra's heaven are found the spirits of the natural

world wind, thunder, fire, water clouds, plants, stars and planets. Recreation

is provided by the singing and dancing of the Apsaras and Gandharvas, celestial

spirits; heroes or divine warriors perform feats of skill and holy rites are

performed. Divine messengers pass to and fro in their celestial chariots. The

heaven presided over by the warrior god was thought to be especially the abode,

permanent or temporary, of warriors. Thus in the Mahabharata Indra receives his

son Arjuna, who is exceptionally skilled in military arts, and keeps him for

several years on Mount Meru and he welcomes the fallen heroes both sides to his

heaven, all those who have performed their warrior’s duty being admitted. Some

of those who enter receive special privileges, such as Bhishma, who resumed his

place as one of the Vasus, Indra’s advisers.

Yama's

role changed with the growth of these other heavens and the idea that heaven

was the reward for virtue, rather than a place where most of the dead were

received unless they had the misfortune of having no children to perform the

proper sacrifices for them. At first the idea of going to the abode of the

fathers was simply less desirable than that of being received with special honors

by the gods later this developed into the notion that Yama's kingdom was not

heaven but hell, where the tortures were pictured with growing elaboration, and

Yama himself became a figure of terror. Opinions differ as to how many hells

there are in his abode some say hundreds of thousands others say twenty-eight,

or only seven. The tortures meted out are peculiarly suited to the sinner's

offence. Thus cruel men are boiled in oil those who are unnecessarily cruel to

animals are consigned to a place where a monster tears them to pieces without

ever killing them those who kill Brahmins to a hell where the bottom is a

furnace and the top a frying pan oppressive kings are crushed between two

rollers; those who kill mosquitoes are tortured by sleeplessness the

inhospitable are turned into worms and cast into a hell where they eat each

other those who marry out-side their caste are forced to embrace red hot human

forms rulers and ministers who provoke religious dissension are thrown into a

river full of the most horrible impurities where they are boiled and fed upon

by aquatic animals.

Just

as the vulgar had personalized the concept of Brahma as creator, so they

misunderstood the Brahmanic philosophers' growing belief in metempsychosis or

transmigration of souls, samsara, and the possibility of ultimate release from

the eternal cycle of rebirths by identification of the individual soul with the

universal spirit.

The

common belief was that the wicked went south to one of Yama's hells, or were

reborn as worms, moths or biting serpents, while the good were sent either to

the abode of the fathers on a path which passed south-east through the moon, or

they went north-west, in the direction of the gods, to the sun. But

distinctions were made between different sorts of the virtuous just as they

were made among the wicked. Yama ceased to preside over the abode of the

fathers and the gods no longer inhabited that region, having moved to one of

the various heavens. Those who now followed the path to the abode of the

fathers had dutifully obeyed their dharma they had offered sacrifices, given

alms generously and performed austerities in other words they had followed

tradition. Such ones pass first into smoke, then into night, then arrive at the

abode of the fathers, and finally pass on to the moon. There (by association of

Soma, moon, and soma, ambrosia) they become the food of the gods but they are

given out from the gods into space, and from air pass successively into clouds,

into rain, and so return to earth where, becoming food, they give rise to the

principle of life in man and woman and so emerge into the world again. Akin to

these beliefs were those that the stars were the souls of the dead

(particularly of saints and heroes) or else that they were the souls of dead

women.

The

common belief was that the wicked went south to one of Yama's hells, or were

reborn as worms, moths or biting serpents, while the good were sent either to

the abode of the fathers on a path which passed south-east through the moon, or

they went north-west, in the direction of the gods, to the sun. But

distinctions were made between different sorts of the virtuous just as they

were made among the wicked. Yama ceased to preside over the abode of the

fathers and the gods no longer inhabited that region, having moved to one of

the various heavens. Those who now followed the path to the abode of the

fathers had dutifully obeyed their dharma they had offered sacrifices, given

alms generously and performed austerities in other words they had followed

tradition. Such ones pass first into smoke, then into night, then arrive at the

abode of the fathers, and finally pass on to the moon. There (by association of

Soma, moon, and soma, ambrosia) they become the food of the gods but they are

given out from the gods into space, and from air pass successively into clouds,

into rain, and so return to earth where, becoming food, they give rise to the

principle of life in man and woman and so emerge into the world again. Akin to

these beliefs were those that the stars were the souls of the dead

(particularly of saints and heroes) or else that they were the souls of dead

women.

Those

virtuous deceased who were allowed to follow the 'path of the gods' were those

who in their lifetime had faith who, in other words, had attained fusion with

the universal spirit and so won release from samsara. The stages of their

journey into the after-life are as follows: the fire of their funeral pyre purifies

their earthly natures, which then become flames themselves they pass next into

day, into the world of the gods and into lightning. They are then con-ducted by

the Supreme Being into the realm of Brahman, the universal divine spirit which

is without beginning or end and is without decay. From this realm there is no

return, and here they achieve immortal bliss.

Among

people clinging to ideas of an after-life spent in the presence of the Vedic

gods, the so-called 'path of the gods' was easily misunderstood. Despite the

general acceptance of the idea of metempsychosis, or rebirth according to karma

(destiny created by actions in former lives), the older beliefs still crept in.

Thus it was held that those who had led virtuous lives were permitted a break

in the cycle of their rebirths by staying some time in lndra's heaven. Some

still held to the old view that they were allowed to reap the benefit of their

good action in Indra's heaven before serving their allotted time in hell.

Alternatively like Yudhisthira in the Mahabharata and like all kings who by

nature of their calling cannot fail to commit some injustice they suffer a vision

of hell before being led to heaven.

Among

people clinging to ideas of an after-life spent in the presence of the Vedic

gods, the so-called 'path of the gods' was easily misunderstood. Despite the

general acceptance of the idea of metempsychosis, or rebirth according to karma

(destiny created by actions in former lives), the older beliefs still crept in.

Thus it was held that those who had led virtuous lives were permitted a break

in the cycle of their rebirths by staying some time in lndra's heaven. Some

still held to the old view that they were allowed to reap the benefit of their

good action in Indra's heaven before serving their allotted time in hell.

Alternatively like Yudhisthira in the Mahabharata and like all kings who by

nature of their calling cannot fail to commit some injustice they suffer a vision

of hell before being led to heaven.

Pantheism and Polytheism

Paradoxically

in an age preoccupied with systematizing beliefs, the Brahmanic period and its

aftermath was a time of religious confusion. New systems were constantly evolved

while the old were retained, and myths had to be elaborated to explain both the

trend to pantheism spearheaded by the priesthood's abstractions and the struggles

for supremacy within the old Vedic pantheon of deities such as Vanilla, Indra,

Mitra, Agni and Soma. As a compromise between these trends Varuna was most

often given the role of a pantheistic god, though Brahma was considered to be

the All-god or universal spirit behind him. Thus Brahma the creator had become

identical with Brahman the world spirit. Other deities were subdivided and

given special names for each of their functions, a process aided by the

converse trend of absorption of lesser deities by the greater ones. For

example, Surya was given supplementary names meaning `nourisher' (Savitri),

'the brilliant' (Vivasvat), 'light-maker', 'day-maker', 'lord of day', 'eye of

the world', 'witness of the deeds of men', 'king of the constellations',

'possessed of rays', 'having a thousand rays', 'shorn of his beams' (a

reference to a myth involving Visvakarma).

A

revival of early trends in the growth of Indian beliefs further complicated the

pattern. Thus the early Aryan influences were brought to the fore, as is shown

by the attention paid to Agni (though he was probably of Indian origin), and to

the Sun and the Moon, as well as the significance attached to the opposition of

light and dark, which symbolize gods and demons, heaven and hell. Dravidian

trends can be discerned in the rise to importance of female deities as powers

in their own right rather than as passive consorts to their divine husbands and

behind this the growing concern with sacrifice and fertility cults. Most

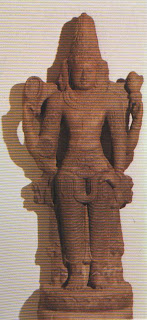

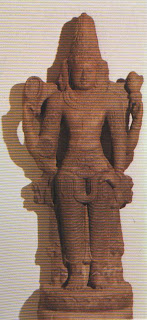

important of all was the appearance of Shiva and the rise of Vishnu. While

Shiva is partly a development from Rudra, he is equally reminiscent of the

pre-Aryan, yogic Lord of the Beasts deity, while his consorts resemble the

sacrifice-exacting mother-goddesses of the same r period. Vishnu is less like

his Vedic namesake than like another deity of non-Aryan origin, Varuna.

A

revival of early trends in the growth of Indian beliefs further complicated the

pattern. Thus the early Aryan influences were brought to the fore, as is shown

by the attention paid to Agni (though he was probably of Indian origin), and to

the Sun and the Moon, as well as the significance attached to the opposition of

light and dark, which symbolize gods and demons, heaven and hell. Dravidian

trends can be discerned in the rise to importance of female deities as powers

in their own right rather than as passive consorts to their divine husbands and

behind this the growing concern with sacrifice and fertility cults. Most

important of all was the appearance of Shiva and the rise of Vishnu. While

Shiva is partly a development from Rudra, he is equally reminiscent of the

pre-Aryan, yogic Lord of the Beasts deity, while his consorts resemble the

sacrifice-exacting mother-goddesses of the same r period. Vishnu is less like

his Vedic namesake than like another deity of non-Aryan origin, Varuna.

Popular

and priestly ideas on all these deities differed widely. Confusion fostered the

rampant growth of explanatory mythology, some of which seems to be scholarly

and philosophical, though much of it must have sprung from the popular

imagination.

Meanwhile

the priests continued to enhance their status by the development of new ideas

on the subject of sacrifice. Sacrifices, usually in the form of offerings of

soma or, later, of milk or curds, were held to be essential for the maintenance

of the gods' strength and for the continued progression of the universe on its

appointed cycle. The priests therefore gained ascendancy over the gods, who

depended upon them for their sustenance, and while they grew relatively weaker

the priests grew in power until, finally, they were openly said to have greater

eminence than the gods they served.

So

the priests, with their mastery of sacrifice, were the first to emancipate

themselves from the dominion of the gods. The sages carried this trend one

stage further, for by austerities and the acquisition of knowledge they could

become identified with the world soul even before death and, as we have seen

with Manu, could survive even the periodic cataclysms and act as creator, thus

surpassing even the reward of release from the pattern of rebirth.

So

the priests, with their mastery of sacrifice, were the first to emancipate

themselves from the dominion of the gods. The sages carried this trend one

stage further, for by austerities and the acquisition of knowledge they could

become identified with the world soul even before death and, as we have seen

with Manu, could survive even the periodic cataclysms and act as creator, thus

surpassing even the reward of release from the pattern of rebirth.

The

priests reconciled the two approaches by declaring that worship of deities and

ritual sacrifice were appropriate for the active stages of a man's life, while

the attempt to loosen the bonds of worldly illusion through detachment and

self-enlightenment might be made at the end of life. The inconsistency between

priestly cults and the mystical beliefs of the Upanishadic philosophers was one

of the factors leading to the growth of many heresies.

Among

these were the Jain movement, with its concentration on personal salvation

through austerities and ahimsa (harmlessness), its belief that the gods of the

old pantheon were unable to reach the spiritual heights attainable by holy men,

and its rejection of the idea of a supreme deity in favour of an Absolute consisting

of a plurality of souls.

Buddhism,

another heretical movement of the fifth century B.C., similarly rejected the priesthood

(Buddha was a member of the warrior caste, a Kshatriya, like Mahavira), and

caste in general. Buddhism, like the cults of the Hindu revival, is rooted in

earlier beliefs, for example the mythology of light and dark (Buddha's was the

dynasty of the Sun), and certain pre-Aryan beliefs about rebirth through death

(fertility through sacrifice) and about detachment. Buddhism became the

dominant religion for almost a millennium among the ruling classes, and in a

popularized form which later supplied it with a mythology was commonly

practised by the masses.

But

Vedic deities or their derivatives continued to be worshipped, and fire and

soma cults were widespread Their priests could offer the further attraction of

rites of passage for the important junctures of human life such as birth,

marriage and death lacking in Buddhism. The substratum of continuing belief in

the old gods was the foundation on which the Hindu revival of the fifth century

A.D. was built.

The

new cults offered the more readily acceptable idea of incarnational deities and

used ancient myths as the core of the religion. But they also incorporated in

their teaching many of the philosophical ideas from the earlier Upanishads of

the fifth century B.C., which were the point of departure for Buddha. Hinduism thus

became an all-embracing faith, able to claim even that Buddha was merely a

manifestation or avatar of its own supreme deity. Where the Brahmanic age

postulated a father god or creator, and Upanishadic teaching suggested that beyond

the creator god there was a universal spirit or supreme deity with which the

spiritually gifted might become united by the path of meditation with or without

austerities, Hindu belief identified the gods of the supreme triad with the universal

spirit, but suggested that they not only embraced within their natures the gods

of the old pantheon but also, through the notion of avatars, that they might

become incarnate in the form of heroes on earth.

The

new cults offered the more readily acceptable idea of incarnational deities and

used ancient myths as the core of the religion. But they also incorporated in

their teaching many of the philosophical ideas from the earlier Upanishads of

the fifth century B.C., which were the point of departure for Buddha. Hinduism thus

became an all-embracing faith, able to claim even that Buddha was merely a

manifestation or avatar of its own supreme deity. Where the Brahmanic age

postulated a father god or creator, and Upanishadic teaching suggested that beyond

the creator god there was a universal spirit or supreme deity with which the

spiritually gifted might become united by the path of meditation with or without

austerities, Hindu belief identified the gods of the supreme triad with the universal

spirit, but suggested that they not only embraced within their natures the gods

of the old pantheon but also, through the notion of avatars, that they might

become incarnate in the form of heroes on earth.

Hinduism's

essential difference from Buddhism lies in this concern with events on earth

and in the way in which it developed the Brahmanic innovation of dharma. Dharma

became righteousness and justice embodied in social, caste obligations. To

follow dharma was now the path to salvation rather than the mere performance of

sacrifices. `Worldliness.' had another consequence. More rigorous sages taught

physical asceticism, instead of the debased sacrificial cult to attain

spiritual disengagement and thus fusion with the universal spirit. But just as

in the popular mind the yogi was admired for his physical prowess rather than

for his spiritual achievement, so the new cults of Vishnu and Shiva, originally

conceived as a spiritual counter to Buddhist abstractions, came in many cases

to foster grosser polytheism and a return to pre-Vedic beliefs. The reversion

to these is clearly seen in the great epics. Though the Mahabharata received

its final form about the first century B.C., was written down in the fifth

century A.D. and continues to be considered scriptural to the present day, it

was a collection of the myths current from about 8oo B.C. onwards.

Writer – Veronica Ions

Read Also:

Yama's

heaven was not without rivals, and in particular it was challenged by the

splendors and delights of the heavens of Varuna and Indra. Varuna in his heaven

was no longer judge of the dead, as he had been when seated beside Yama; he was

already lord of the ocean. The heaven, which was constructed within the sea by

Tvashtri or Visvakarma, had walls and arches of pure white, surrounded by

celestial trees made of brilliant jewels which always bore blossom and fruit

birds sang everywhere. In the white assembly house Varuna sat enthroned with

his queen, both decked with jewels, ornaments of gold, and flowers. They were

attended by the minor deities the Adityas, the Nagas (serpents), the Daityas

and Danavas (ocean demons), the spirits of the rivers, seas and other waters,

and the personified forms of the cardinal points and the mountains.

Yama's

heaven was not without rivals, and in particular it was challenged by the

splendors and delights of the heavens of Varuna and Indra. Varuna in his heaven

was no longer judge of the dead, as he had been when seated beside Yama; he was

already lord of the ocean. The heaven, which was constructed within the sea by

Tvashtri or Visvakarma, had walls and arches of pure white, surrounded by

celestial trees made of brilliant jewels which always bore blossom and fruit

birds sang everywhere. In the white assembly house Varuna sat enthroned with

his queen, both decked with jewels, ornaments of gold, and flowers. They were

attended by the minor deities the Adityas, the Nagas (serpents), the Daityas

and Danavas (ocean demons), the spirits of the rivers, seas and other waters,

and the personified forms of the cardinal points and the mountains.  The

common belief was that the wicked went south to one of Yama's hells, or were

reborn as worms, moths or biting serpents, while the good were sent either to

the abode of the fathers on a path which passed south-east through the moon, or

they went north-west, in the direction of the gods, to the sun. But

distinctions were made between different sorts of the virtuous just as they

were made among the wicked. Yama ceased to preside over the abode of the

fathers and the gods no longer inhabited that region, having moved to one of

the various heavens. Those who now followed the path to the abode of the

fathers had dutifully obeyed their dharma they had offered sacrifices, given

alms generously and performed austerities in other words they had followed

tradition. Such ones pass first into smoke, then into night, then arrive at the

abode of the fathers, and finally pass on to the moon. There (by association of

Soma, moon, and soma, ambrosia) they become the food of the gods but they are

given out from the gods into space, and from air pass successively into clouds,

into rain, and so return to earth where, becoming food, they give rise to the

principle of life in man and woman and so emerge into the world again. Akin to

these beliefs were those that the stars were the souls of the dead

(particularly of saints and heroes) or else that they were the souls of dead

women.

The

common belief was that the wicked went south to one of Yama's hells, or were

reborn as worms, moths or biting serpents, while the good were sent either to

the abode of the fathers on a path which passed south-east through the moon, or

they went north-west, in the direction of the gods, to the sun. But

distinctions were made between different sorts of the virtuous just as they

were made among the wicked. Yama ceased to preside over the abode of the

fathers and the gods no longer inhabited that region, having moved to one of

the various heavens. Those who now followed the path to the abode of the

fathers had dutifully obeyed their dharma they had offered sacrifices, given

alms generously and performed austerities in other words they had followed

tradition. Such ones pass first into smoke, then into night, then arrive at the

abode of the fathers, and finally pass on to the moon. There (by association of

Soma, moon, and soma, ambrosia) they become the food of the gods but they are

given out from the gods into space, and from air pass successively into clouds,

into rain, and so return to earth where, becoming food, they give rise to the

principle of life in man and woman and so emerge into the world again. Akin to

these beliefs were those that the stars were the souls of the dead

(particularly of saints and heroes) or else that they were the souls of dead

women.  Among

people clinging to ideas of an after-life spent in the presence of the Vedic

gods, the so-called 'path of the gods' was easily misunderstood. Despite the

general acceptance of the idea of metempsychosis, or rebirth according to karma

(destiny created by actions in former lives), the older beliefs still crept in.

Thus it was held that those who had led virtuous lives were permitted a break

in the cycle of their rebirths by staying some time in lndra's heaven. Some

still held to the old view that they were allowed to reap the benefit of their

good action in Indra's heaven before serving their allotted time in hell.

Alternatively like Yudhisthira in the Mahabharata and like all kings who by

nature of their calling cannot fail to commit some injustice they suffer a vision

of hell before being led to heaven.

Among

people clinging to ideas of an after-life spent in the presence of the Vedic

gods, the so-called 'path of the gods' was easily misunderstood. Despite the

general acceptance of the idea of metempsychosis, or rebirth according to karma

(destiny created by actions in former lives), the older beliefs still crept in.

Thus it was held that those who had led virtuous lives were permitted a break

in the cycle of their rebirths by staying some time in lndra's heaven. Some

still held to the old view that they were allowed to reap the benefit of their

good action in Indra's heaven before serving their allotted time in hell.

Alternatively like Yudhisthira in the Mahabharata and like all kings who by

nature of their calling cannot fail to commit some injustice they suffer a vision

of hell before being led to heaven.  A

revival of early trends in the growth of Indian beliefs further complicated the

pattern. Thus the early Aryan influences were brought to the fore, as is shown

by the attention paid to Agni (though he was probably of Indian origin), and to

the Sun and the Moon, as well as the significance attached to the opposition of

light and dark, which symbolize gods and demons, heaven and hell. Dravidian

trends can be discerned in the rise to importance of female deities as powers

in their own right rather than as passive consorts to their divine husbands and

behind this the growing concern with sacrifice and fertility cults. Most

important of all was the appearance of Shiva and the rise of Vishnu. While

Shiva is partly a development from Rudra, he is equally reminiscent of the

pre-Aryan, yogic Lord of the Beasts deity, while his consorts resemble the

sacrifice-exacting mother-goddesses of the same r period. Vishnu is less like

his Vedic namesake than like another deity of non-Aryan origin, Varuna.

A

revival of early trends in the growth of Indian beliefs further complicated the

pattern. Thus the early Aryan influences were brought to the fore, as is shown

by the attention paid to Agni (though he was probably of Indian origin), and to

the Sun and the Moon, as well as the significance attached to the opposition of

light and dark, which symbolize gods and demons, heaven and hell. Dravidian

trends can be discerned in the rise to importance of female deities as powers

in their own right rather than as passive consorts to their divine husbands and

behind this the growing concern with sacrifice and fertility cults. Most

important of all was the appearance of Shiva and the rise of Vishnu. While

Shiva is partly a development from Rudra, he is equally reminiscent of the

pre-Aryan, yogic Lord of the Beasts deity, while his consorts resemble the

sacrifice-exacting mother-goddesses of the same r period. Vishnu is less like

his Vedic namesake than like another deity of non-Aryan origin, Varuna.  So

the priests, with their mastery of sacrifice, were the first to emancipate

themselves from the dominion of the gods. The sages carried this trend one

stage further, for by austerities and the acquisition of knowledge they could

become identified with the world soul even before death and, as we have seen

with Manu, could survive even the periodic cataclysms and act as creator, thus

surpassing even the reward of release from the pattern of rebirth.

So

the priests, with their mastery of sacrifice, were the first to emancipate

themselves from the dominion of the gods. The sages carried this trend one

stage further, for by austerities and the acquisition of knowledge they could

become identified with the world soul even before death and, as we have seen

with Manu, could survive even the periodic cataclysms and act as creator, thus

surpassing even the reward of release from the pattern of rebirth.  The

new cults offered the more readily acceptable idea of incarnational deities and

used ancient myths as the core of the religion. But they also incorporated in

their teaching many of the philosophical ideas from the earlier Upanishads of

the fifth century B.C., which were the point of departure for Buddha. Hinduism thus

became an all-embracing faith, able to claim even that Buddha was merely a

manifestation or avatar of its own supreme deity. Where the Brahmanic age

postulated a father god or creator, and Upanishadic teaching suggested that beyond

the creator god there was a universal spirit or supreme deity with which the

spiritually gifted might become united by the path of meditation with or without

austerities, Hindu belief identified the gods of the supreme triad with the universal

spirit, but suggested that they not only embraced within their natures the gods

of the old pantheon but also, through the notion of avatars, that they might

become incarnate in the form of heroes on earth.

The

new cults offered the more readily acceptable idea of incarnational deities and

used ancient myths as the core of the religion. But they also incorporated in

their teaching many of the philosophical ideas from the earlier Upanishads of

the fifth century B.C., which were the point of departure for Buddha. Hinduism thus

became an all-embracing faith, able to claim even that Buddha was merely a

manifestation or avatar of its own supreme deity. Where the Brahmanic age

postulated a father god or creator, and Upanishadic teaching suggested that beyond

the creator god there was a universal spirit or supreme deity with which the

spiritually gifted might become united by the path of meditation with or without

austerities, Hindu belief identified the gods of the supreme triad with the universal

spirit, but suggested that they not only embraced within their natures the gods

of the old pantheon but also, through the notion of avatars, that they might

become incarnate in the form of heroes on earth.

0 Response to "About Developments of the Brahmanic Age "

Post a Comment