The

Hindi poets of the 16th and 17th centuries were keen observers of human nature.

Their classification of women according to age, experience, physical and mental

traits, situation, moods and sentiments provided themes for the Kangra

painters. The most important of these was Keshav Das, a Brahmin from Orchha in

Bundelkhand. He was the court poet of Indrajit Shah of Orchha and he wrote his

famous love poem Rasikapriya in A.D. 1591. A number of Nayika paintings from

Kangra are inscribed with texts from the Rasikapriya.

The

Rasikapriya is written in vivid style. The language is musical and the

expression frank and forthright. The sentiment of love is at the same time

expressive of a passionate, sincere religion. "The soul's devotion to the

deity is pictured by Radha's self-abandonment to her beloved Krishna and all

the hot blood of Oriental passion is encouraged to pour forth one mighty flood

of praise and prayer to the Infinite Creator, who waits with loving,

out-stretched arms to receive the worshipper into His bosom, and to convey him

safely to eternal rest across the seemingly shoreless Ocean of Existence."

These

Hindi love poems are noted for their bright and compact style. Neat little

pictures are painted in a few words particularly in the dohas or couplets.

These lend themselves particularly to painting and in fact the Kangra

miniatures are really poems dressed in line and colour.

According

to Keshav Das, women are classified into four types: the Lotus (Padmini), the

Variegated (Chitrini), the Conch-like (Sankhini) and Elephant-like (Hastini).

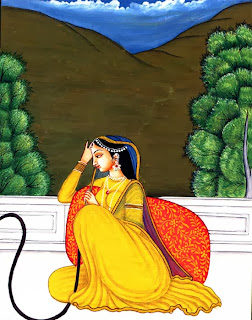

Padmini

is a beautiful nayika, emitting the fragrance of the lotus from her body,

modest, affectionate and generous, slim, free from anger, and with no great

fondness for love-sports. Bashful, intelligent, cheerful, clean and

soft-skinned, she loves clean and beautiful clothes. She has a golden

complexion.

"Shedding

flowers from her smile, she is sensitive to tender emotions and knows well the

art of love. She is to be preferred to all Pannagis, Nagis, Asuris and Suris.

All the affection which the people of Vraja bestow on her is in fact too

meagre. Thousands of fond desires hover round her like bees. Such indeed is

Radha, that unique divine champaka bud fashioned by the Creator."

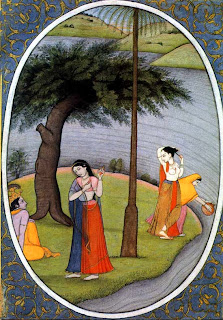

This

lovely painting is from Nurpur front the collection of the Wazir family, and

illustrates the beauty of a "lotus" woman.

The nayikas

are further classified as one's own (svakiya), another's (parakiya) and

anybody's (samanya).

The

svakiya heroines are classified into eight broad types (hence the name astanayika,

eight heroines). It may be mentioned that the terms "lover" and

"husband" are almost synonymous in it India, for unlike in the West,

free love among the sexes is, to all intents and purposes, unknown. The eight Nayikas

are as follows:

Svadhinapatika

Utka,

or Utkanthita Vasakasayya, or Vasakasajja

Abhisandhita

Khandita

Prositapatika

or Prosita-Preyasi

Vipralabdha

Abhisarika

Svadhinapatika

is the heroine to whose virtues her Lord is devoted and to whom he is bound in

love and is perpetually a companion.

The

heroine is represented in Kangra painting as Radha seated on a chauki, while

Krishna washes or presses her feet and legs. He is also shown applying lac dye

to her feet. She looks with pride and self-confidence at the completely subdued

and docile Krishna.

In

literature, the heroine is described thus by the sakhi: "O Radha, Krishna

is the life-giver of Vraja and a darling of Brahma; and the goddesses,

demon-women, Surya and Lakshmi, are never tired of singing his praise. And you,

only a mean little shepherdess, have your feet cleaned by him and he, the Lord

of the Universe, is constantly clinging to you like your shadow. He takes care

of your pettiest affairs and resides in you as the image dwells in the mirror,

no matter if the angels sound trumpets in his praise. He runs after the chariot

of your desires like the water of the Ganges of yore which followed in a

winding trail the chariot of Bhagiratha. Your words are like the Scriptures to

him. It is, therefore, absurd to try to dissuade him from doing all this even

for the sake of saving him from calumny."

Utka

is the anxious heroine whose lover has failed to keep his appointment at the

promised hour.

She

is represented as standing on a bed of leaves covered with jasmine flowers

under a tree beside a stream. She has adorned the trunk of the tree with

garlands of jasmine. A pair of love-birds are perched on the tree. The heavy

dark clouds are lit up by a flash of lightning. The heroine who is like the

dryad of some enchanted forest eagerly awaits the arrival of her lover. At

times deer are shown near the trysting place, sniffing at the wind or drinking

water from a lotus lake.

The utka

soliloquizes thus: "Is he detained at home on business or by company, or

is it an auspicious day of fasting? Is it a quarrel, or the dawning of divine

wisdom which keeps him away from me? Is he in pain, or is it some treachery

that keeps him from meeting me, or the impeding waters, or the terrifying

darkness of the night? Or is he testing my fidelity? O my poor heart! You will

never know the cause of this delay."

The

vasakasayya being desirous of union with her Lord waits for me on the doorstep.

Her body, white like the sandal tree, glows like a lamp, and her garments, blue

as the clove-vine creepers, flutter round her fair soft limbs. She is startled

at the slightest sound of birds or animals. She speaks softly and relates her

heart's desires to her confidant as she casts the spell of her enchantment.

The

heroine is represented in Kangra painting as a woman standing at her bedroom

door, happy and anxious for her lover's expected arrival. Brisk preparations

for his reception are being made in the household; a woman sweeps the

courtyard, another empties stale water from a flask, and the bedroom is tidied

up. The lover sits in a ferry-boat on the other side of the river, close to a

pair of sarus cranes.

Abhisandhita

is the heroine who disregards her lover's devotion, but is full of remorse in

his absence, for she feels the pangs of separation all the more. In the

paintings on the subject, the lovers are shown as having quarrelled. Krishna

clad in yellow with a peacock's feather in his turban is about to leave. There

is intense sorrow and gloom on Radha's face. Krishna has tried to assuage her

anger, but she will not relent and repulses him in anger. But as Krishna turns

his back and is about to depart, she regrets her harsh words.

"How

foolish of me", she thinks, "not to have responded when he spoke to

me repeatedly! I was adamant and would not yield when he fell at my feet, but

now my limbs seem to melt like butter. Woe

to me! I am helpless and beyond all cure! When my dearest Lord tried to

propitiate me, I would not listen, unfortunately I didn't relent; and my soul

is filled with the bitterest mortification and re-pentance." Radha's

fingers are gracefully drawn and her black tresses are visible beneath the

transparent dupatta. The curves of her delicate body and her mood of mixed

resentment and sorrow are well portrayed.

Khandita

is the heroine whose lover fails to keep his appointment at night, but comes

the next morning after spending the night with another girl. The heroine

upbraids her lover.

"What

the ears have never heard, eyes have actually seen. Such are the praises sung

in your honour all over the place! Unmindful of your family honour, you have

been feasting yourself like a crow on discarded crumbs; and your vile appetite

grows rapacious. Unable to discriminate between good and evil, you fall upon

the feet of those who denounce you. Tell me, O Ghanasyama, after seducing whose

honour have you come here this morning to my house to hide like an owl your

ominous face?”

In

the pictures of the khandita nayika, an angry and offended heroine is shown

upbraiding the lover who has entered her courtyard, abashed and with a guilty

face.

Prositapatika

is the heroine whose husband is away for some time on business.

In a

painting from Guler, the heroine on hearing the rumble of the clouds goes up to

the balcony. She wears a spotted dupatta, and looks eagerly at the flying sarus

cranes, while a peacock, symbol of the absent lover, raises his head in

exultation. It is about to rain, and the lady prays to the passing clouds for

the safe return of her lover. The painting could well be an illustration of the

following verse:

When she hears the thundering of the autumn clouds, the

moon-face bids her sakhis not to go upon the roof,

And seeing that the ground was full of drops of rain, the

friendly nayikas gave her unto the (pleasant) crying of the peacocks and the chatakas,

The fawn-eyed lady wears a spotted veil that's bright of hue,

and sirisa flowers are deftly woven in her tresses,

With waning pride she stands and looks, and prays to the

lightning and the leaden clouds, 'Give me news of my dear Dark One.'

Vipralabdha

is the disappointed heroine who has waited in vain for her lover throughout the

night. She is shown standing under a tree on the edge of a bed of leaves,

tearing off her ornaments in disgust and flinging them on the ground. The empty

space in the background symbolises her loneliness, frustration and deep

distress. Her feelings are described thus:

Flowers are like arrows, fragrance becomes ill-odour, and

pleasant bowers like fiery furnaces,

Gardens are like the wild woods, Ah Kesava! the moon-rays burn

her body as though with fever,

Love like a tiger holds her heart, no watch of the night

brings any gladness,

Songs have the sound of abuse, pan has the taste of poison and

every jewel burns her like a firebrand.

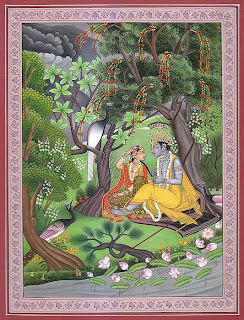

Abhisarika

is the heroine who goes out to meet her lover. She is classified under various

heads by different poets, and is a favourite theme with Kangra artists. The krsnabhisarika

and suklabhisarika are the heroines who fare forth to meet their lovers during

dark and bright nights, respectively.

In a

charming picture of krsnabhisarika, the lady wearing a blue veil goes out to

seek her lover. It is a dark night with black clouds and there are intermittent

flashes of lightning. The forest is infested with snakes and haunted by

churails. Undeterred by the terrors of the jungle, the storm, the snakes, the

goblins and the darkness, the heroine, filled with passion for her lover, goes

to seek him.

According

to Kamasutra, desire in the heart of woman waxes and wanes with the moon. When

the moon is full, the woman’s desires are particularly ardent. In paintings of

suklabhisarika, she is shown going forth in search of her lover. The full moon

in the sky fills the atmosphere with its silvery beams, and its pale cool light

is painted with remarkable skill. The Drapery of the woman and her delicate

feature are suffused with the mellow light.

Guru

Gobind Singh, in his Dasama Grantha, describe Radha, the suklabhisarika, thus: “Radhika

went out in the light of the white soft moon, wearing a white robe to meet her Lord.

It was white everywhere and hidden in it, she appeared like the Light itself in

search of Him.

Writer Name: M.S. Randhawa

"Every

work of art is fragrant of its time," says Laurence Binyon. The religion

of Vaishnavism and particularly, the Radha-Krishna cult provided Kangra

painters with inspiration while in Sansar Chand they found a patron who

honoured and encouraged them. It was in such happy circumstances that these

artists created a style which combines elegance with nervous grace. There is

delicacy and sensitivity in the line, combined with rare beauty of colour. For

almost forty years these artists were aglow with inspiration and they created

these memorable paintings which communicate spiritual concepts of the Krishna

cult so vividly. It is not a spiritual art in the Western Christian sense,

where spirit and body are regarded as two separate entities. It is not gloomy, cold

and forbidding, but is an art which is a happy blend of the sensuous and the

spiritual. The spirituality is not chilled by an asceticism which is disdainful

of female loveliness and the delights of love. In fact, its spirituality is

very much based on flesh and blood. It is an art which glorifies female beauty

and revels in the loveliness of the female form.

This

art is an interpretation of the religious creed of Vaishnavism, the religion of

love, which inspired the poetry of Keshav Das, Sur Das, and Bihari. No doubt,

the verses of these poets inspired whole cycles of painting in Rajasthan, but

the manner in which Khushala, the Kangra artist, matched his imagination with

the poet Bihari's is unique indeed. With what depth of feeling, and sincerity

he has painted the love poems of Bihari! As in the art of China and Japan,

there is a close association of poetry and painting in the art of Kangra. The

aim of the artist was to embody in the picture the emotion caused by reading

the poem. In this he achieved unique success, and in the process of translating

poetry into painting, he also evolved an art which has lyrical quality. This

explains the emotive power of these paintings, which are really love lyrics

translated into line and colour. In no other art does one see such a successful

and harmonious association of literary and plastic ideas.

The

aesthetics of an age grows out of its environment, physical, cultural,

spiritual, technological and economic. We have already mentioned the cultural

and spiritual background of Kangra painting in the religion and poetry of the

Vaishnavas. We will now explain the influence of physical environment on Kangra

art. 'I do not want to exaggerate the importance of climatic factors,' says

Herbert Read, 'but the fact remains that when-ever an ideological movement whether

merely stylistic or profoundly religious and spiritual is transplanted into a

region of different climatic and material conditions, that movement is

completely transformed. It adapts itself to the prevailing ethos that emanation

of the soil and the weather which is the characteristic spirit of a

community.'" This is what happened to Mughal styles of painting when they

reached the Punjab hills. Mughal painting had already achieved excellence in

portraiture and scenes of the zenana. The fluid line and delicate colouring of

some of the Mughal paintings is truly admirable. It is the religious paintings,

however, in which princes and emperors are shown in conversation with saints,

which are the most inspired products of the Mughal school, and have a rare

mystic quality which is the hall-mark of great art. Such paintings are,

however, few and the main preoccupations of the Mughal artists were durbar and

hunting scenes, and portraiture. It is only when the later Mughal style reached

the valley of Kangra and absorbed the elements of a new environment that it

blended beauty and lyrical quality with exquisite flow of line. Mughal

paintings were usually painted against the background of the drab and

monotonous plains of northern India. When the artists introduced the gently

undulating hills, rivulets and the characteristic vegetation of the Shivaliks,

painting in the Kangra valley acquired grace and loveliness. In fact, it is the

passionate love of hill scenery which dominates Kangra painting and lends it

charm. The sophistication of the court, its dullness, and regimentation were

forgotten. And instead the atmosphere of the hill village, with its joy,

freedom, contact with nature, and serenity, makes its appearance. Take away the

hills, the rivers, and the groves of trees from these paintings, and see how

much they lose in beauty!

The

aesthetics of an age grows out of its environment, physical, cultural,

spiritual, technological and economic. We have already mentioned the cultural

and spiritual background of Kangra painting in the religion and poetry of the

Vaishnavas. We will now explain the influence of physical environment on Kangra

art. 'I do not want to exaggerate the importance of climatic factors,' says

Herbert Read, 'but the fact remains that when-ever an ideological movement whether

merely stylistic or profoundly religious and spiritual is transplanted into a

region of different climatic and material conditions, that movement is

completely transformed. It adapts itself to the prevailing ethos that emanation

of the soil and the weather which is the characteristic spirit of a

community.'" This is what happened to Mughal styles of painting when they

reached the Punjab hills. Mughal painting had already achieved excellence in

portraiture and scenes of the zenana. The fluid line and delicate colouring of

some of the Mughal paintings is truly admirable. It is the religious paintings,

however, in which princes and emperors are shown in conversation with saints,

which are the most inspired products of the Mughal school, and have a rare

mystic quality which is the hall-mark of great art. Such paintings are,

however, few and the main preoccupations of the Mughal artists were durbar and

hunting scenes, and portraiture. It is only when the later Mughal style reached

the valley of Kangra and absorbed the elements of a new environment that it

blended beauty and lyrical quality with exquisite flow of line. Mughal

paintings were usually painted against the background of the drab and

monotonous plains of northern India. When the artists introduced the gently

undulating hills, rivulets and the characteristic vegetation of the Shivaliks,

painting in the Kangra valley acquired grace and loveliness. In fact, it is the

passionate love of hill scenery which dominates Kangra painting and lends it

charm. The sophistication of the court, its dullness, and regimentation were

forgotten. And instead the atmosphere of the hill village, with its joy,

freedom, contact with nature, and serenity, makes its appearance. Take away the

hills, the rivers, and the groves of trees from these paintings, and see how

much they lose in beauty!

The

Kangra valley is undoubtedly one of the beauty spots of the world, and people

who are sensitive to beauty of nature, when they happen to visit it, come back

full of praise for it. On the one side is a snow-covered mountain range

towering to an altitude of 16,000 feet above sea-level. Below it is a green,

sloping valley, at an altitude ranging from 3,000 to 4,000 feet, strewn with

enormous lichen-stained boulders. Tropical mangoes and plantains jostle with

temperate cherries, crab apples, medlars and rambling roses. No scenery

presents such sublime and delightful contrasts. Carefully terraced fields,

irrigated by streams which descend from perennial snows, present a picture of

rural loveliness and repose which cannot be seen elsewhere in India. The

terraces sparkle like mosaics of mirrors when they are flooded with water in

the month of June. Then follows the velvet green paddy crop. Green is a

soothing colour but it is hard to match the rich shade of paddy plants which

shine like emeralds in the sun. Nowhere in the vegetable kingdom can we see

such an exquisite shade of green, so comforting and so pleasant. Spread all

over are homesteads of farmers, buried in groves of mangoes, bamboos,

plan-tains and kachnar. Unlike most hillmen, the people of Kangra are conscious

of the beauty of their land. In one of their folk songs, they thus pay homage

to their native hills:

Oh mother Dhauladhar, you have made Kangra a paradise.

Green, green hills, and deep, deep gorges with rivers flowing.

Lithe and handsome young men, and lovely women who speak so

gently.

Oh, my dear land of Kangra, you are unique.

If

common people could feel the beauty of the valley, sensitive artists could not

remain immune to it. In fact, they responded enthusiastically to the charm of

gentle hills and rolling valleys.

If

common people could feel the beauty of the valley, sensitive artists could not

remain immune to it. In fact, they responded enthusiastically to the charm of

gentle hills and rolling valleys.

It

is, however, surprising that though the artists were living and working in a

valley, where the snow-covered mountain range of the Dhauladhar is constantly

in sight, in none of the paintings do we find the snows painted. The Dhauladhar

is perhaps too domineering, cold and forbidding. That is why it seems the

artists preferred painting the gently undulating Shivalik hills among which

they lived.

The

Kangra artists were hereditary painters who worked in the quiet of their

cottages in the sylvan retreats of the Kangra valley. Sons and nephews were

usually accepted as pupils and they served the master artists by carefully

grinding mineral colours, a work requiring skill and patience. It is thus they

were initiated into the art and technique of painting. Life was simple, and the

Rajas provided foodgrains and a cow for milk to the artists. Whenever they

presented a beautiful painting to the Raja, they were handsomely rewarded. Thus

their economic needs were taken care of by their patrons, and they were free to

devote their entire time to painting. Miniature painting requires infinite

patience and care, and it is a type of art which could flourish only in an age

of leisure, under a benevolent feudalistic system. At the close of the

nineteenth century, art also languished because of the lack of patronage. Apart

from this, the inspiration was gone, and the generation of geniuses, who

painted the well-known masterpieces, had also passed away. Why, in particular

periods, certain countries reach a high level of creativeness, is one of the

unsolved riddles of history. The spell of creative enthusiasm which gripped the

Kangra valley for a century and then ebbed away likewise remains only partially

explained.

Here

is an art which celebrates life and love. And with what delicacy the ecstasies

of love are depicted! This art is truly a record of human joy. The eyes of

lovers meet and a world of feeling and tenderness is revealed in them. There

are chance encounters in the courtyard, and Radha who is keeping her secret

from the prying and inquisitive sakhis, conveys her message in the language

which the lovers alone mutually understand. Radha meets Krishna suddenly near

the entrance door of her house. While he looks at her with hungry eyes, she

stands veiled, with her face bent down, and she looks like a painted image, a

picture of innocence, swayed by the crosscurrents of youthful passion and

virgin modesty. We find her gazing at Krishna from the terrace, the windows and

balconies of her home. With what elegance the artist has depicted the

restlessness of love!

Here

is an art which celebrates life and love. And with what delicacy the ecstasies

of love are depicted! This art is truly a record of human joy. The eyes of

lovers meet and a world of feeling and tenderness is revealed in them. There

are chance encounters in the courtyard, and Radha who is keeping her secret

from the prying and inquisitive sakhis, conveys her message in the language

which the lovers alone mutually understand. Radha meets Krishna suddenly near

the entrance door of her house. While he looks at her with hungry eyes, she

stands veiled, with her face bent down, and she looks like a painted image, a

picture of innocence, swayed by the crosscurrents of youthful passion and

virgin modesty. We find her gazing at Krishna from the terrace, the windows and

balconies of her home. With what elegance the artist has depicted the

restlessness of love!

Clad

in a white sari, the lovely girl is cooking. The beauty of her face, and the

charm of her personality have brightened the kitchen.

Another

characteristic of these paintings is the manner in which dramatic relations and

expectancy are expressed through design, as well as expression, on the faces of

the lovers.

Others

are present, and, due to modesty, physical contact is not possible. She glances

at Krishna with loving eyes through her veil, and on some pretext she moves

away brushing her shadow with his shadow.

The

lovers are standing in the balconies of their houses facing each other. Their

fixed gaze has provided a rope on which their hearts travel fearlessly like

rope-dancers.

Demonstrates

the strength, as well as the weakness, of this form of art. While the delicate

profile of the Nayika is so fascinating, the full face of her companion is

positively repulsive. When these artists make an attempt to paint the full face

they fail.

Demonstrates

the strength, as well as the weakness, of this form of art. While the delicate

profile of the Nayika is so fascinating, the full face of her companion is

positively repulsive. When these artists make an attempt to paint the full face

they fail.

Clad

in white, the lady has gone into the moon-light to meet her lover. It is white

everywhere and hidden in it only the fragrance of the body enables her sakhi to

follow her. The white radiance of the moon and its pale silvery light has been

marvellously evoked by the artist.

The

artist has shown considerable skill in painting night scenes. The night is

pitch-dark and the lane is narrow. The lovers coming from opposite directions

brush against each other, and only the light touch of their bodies enables them

to recognize each other. How brilliantly the artist has painted the inky sky,

resplendent with stars!

Against

the background of a paddy field and her home stands the demure village beauty.

Wearing a fillet, and holding a stick, stands she of the slender waist, with

eyes downcast, unconscious of her innocent charm and beauty. A garland

decorates her round breasts.

Excepting

two, all the paintings of the Sat Sal are designed in an oval with an arabesque

in the border.

Apart

from forty paintings, out of which twenty-seven have been reproduced in this

book, there are about twenty drawings or unfinished paintings. This suggests

that the artist who had taken up the project of illustrating the seven hundred

verses of Bihari may have died, leaving his work unfinished. It seems that the

inscriptions on the back of the paintings were written later on. Out of the

paintings reproduced in this book hardly ten bear correct inscriptions. The

remainder have no inscriptions or have wrong ones, the situation shown in the

painting being entirely different from that described in the poem. Out of the

drawings ten are reproduced in this chapter.

The

Nayika sits under a leafless tree, immersed in grief, while her companions show

deep concern. The love-sick Nayika is sitting in the courtyard reclining

against a pillow. Her sakhi thus addresses her: "O deceitful girl! you

cannot conceal your feeling of love, even if you make a million efforts. Your

simulated indifference is itself disclosing that your heart is saturated with

love."

In the

Nayika is sitting behind the trellis and is looking at Krishna, who is standing

below. The poet says, "Although slanderous talk surrounds them, the lovers

do not give up the joy of exchanged glances." The anxiety of the Nayika to

have a glimpse of Krishna is great. The sakhis are standing on the stairs.

Commenting on the eagerness of the Nayika, one says to the other, "Look

hither a while, if you wish to see a marvel. Having torn the fence with her

fingers, she has been looking at him with unblinking eyes for a long

time."

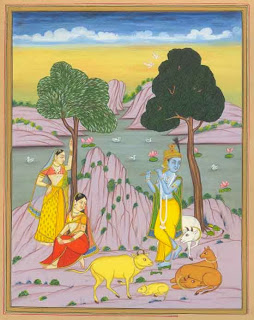

Both

the poetry and painting have a spirit of closeness to life, and in Radha,

Krishna and their friends and playmates, we find farmers and herdsmen of the

Kangra Valley, in their familiar surroundings of thatched cottages, nestling on

the spurs of mountains, against the background of lakes and rivers.

Though

it depicts the life of the rustics in the villages of the valley, Kangra

painting is not a folk art. It is essentially an aristocratic art, the patrons

of which were the Rajas who had fine sensibility and good taste. Thus, like the

best art of Europe, Kangra painting is the art of an elite.

The

Gita Govinda is a forest idyll, and in its Kangra paintings, the drama of the

loves of Radha and Krishna is played in the forest, or along the river-bank. In

the paintings of the Bhagavata Purana, the incidents in the life of the boy

Krishna are depicted against the background of the forests of Vrindavana and

the river Yamuna. It is the trees of the forest, and the current of the river

which are most prominent in these paintings. On the other hand, in the

paintings of the Sat Sal-the background of architecture provides the setting

for the love drama of Radha and Krishna. It is against the background of

straight lines of walls, windows and balconies that the games of love are

carried on by Radha and Krishna, watched by the sakhis.

The

parallel straight lines and right angles create a compositional pattern of

restfulness and calm, illustrating Kafka's observation that 'closed areas are

more stable.' Here we find the beauty of geometry in harmony with the beauty of

the female form. Against the repose of the static architectural compositions,

we feel the restlessness of love. While the architectural setting has

precision, the human figures have a fluid grace matching the elegance of a

waterfall against the straight vertical lines of a mountain. With what gliding

grace lovely female forms flit across courtyards! And always there is a pair of

confidantes discussing the course of love of the divine couple. They are

unhappy and have an expression of serious concern on their faces, when there is

dissension or misunderstanding among the lovers, and they are never tired of

coaxing, cajoling, or giving advice. When the course of love runs smoothly,

they are unrestrainedly happy.

The

knitting together of form and colour into a coordinated harmony is the essential

of great art. In these Kangra paintings, form and colour are so blended that

the effect is musical. To achieve such a harmony, the artist made use of both

line and colour in these paintings. The line which he used is the musical,

rhythmical line, which expresses both movement and mass. The type of line which

Blake admired, and regarded as the golden rule of art as well as life, is this:

"The more distinct, sharp and wiry the bounding line, the more perfect the

work of art, and the less keen and sharp, the greater is the evidence of weak

imagination." And what a rhythm the dancing line creates, a pure limpid

harmony! That is why these pictures are so comforting and so soothing, like the

concertos of great Western composers of music such as Bach and Mozart. This

line was effectively supplemented by colours the blues, yellows, greens, and

reds, the pure colours of earth and minerals, which shine like jewels and have

not been dimmed by the passage of time. The combination of fluid line and

glowing colours ultimately produced an art which combines the beauty of figure

with dignity of pose, set against the calm of the hills.

The

knitting together of form and colour into a coordinated harmony is the essential

of great art. In these Kangra paintings, form and colour are so blended that

the effect is musical. To achieve such a harmony, the artist made use of both

line and colour in these paintings. The line which he used is the musical,

rhythmical line, which expresses both movement and mass. The type of line which

Blake admired, and regarded as the golden rule of art as well as life, is this:

"The more distinct, sharp and wiry the bounding line, the more perfect the

work of art, and the less keen and sharp, the greater is the evidence of weak

imagination." And what a rhythm the dancing line creates, a pure limpid

harmony! That is why these pictures are so comforting and so soothing, like the

concertos of great Western composers of music such as Bach and Mozart. This

line was effectively supplemented by colours the blues, yellows, greens, and

reds, the pure colours of earth and minerals, which shine like jewels and have

not been dimmed by the passage of time. The combination of fluid line and

glowing colours ultimately produced an art which combines the beauty of figure

with dignity of pose, set against the calm of the hills.

Writer Name: M.S. Randhawa

Cosmic Couple

Kama,

lord of desire, catalyst of all creative processes, was reborn the moment

Parvati embraced Shiva. She softened the stern hermit with sweet words; her

smile stirred love in his austere heart. The twang of the love-god's bow and

the fragrance of spring filled the air. Everyone cheered this divine union.

Parvati

made Kailas her home, close to lake Manasarovar. Its snowy peaks served as her

courtyard, its caves became her mansion. There she domesticated Shiva, turned

him into a householder, much to the satisfaction of the gods. In the chilly

waters of Manasarovar, amidst the blooming lotuses and the beautiful swans, she

sported with him. On its shores they danced and sang, captivating the attention

of forest spirits and divine beings. The two complemented each other perfectly.

She was gentle and graceful; he was wild and forceful. Her subtle lasya

tempered his energetic tandav and created perfect harmony, encapsulating the

vibrations of the universe, capturing the music of the spheres.

On

the hill slopes she conversed with Shiva. She asked him questions about the

cosmos, about Nature, about society, life and marriage. Each time he replied,

she asked him a thousand other questions. Skillfully Parvati enticed Shiva into

the ways of the world, arousing his concern for society. Thus his great wisdom,

acquired through aeons of meditating and brooding, was revealed for the good of

the cosmos.

Parvati

was the perfect student, Shiva the perfect teacher. Ultimately the world was

enriched by these sacred conversations; through them was revealed the secrets

of the Vedas, the splendours of the Shaastras and the mysteries of the Tantras.

With

Parvati by his side, Shiva made a declaration: "Let it be known, no

worship or sacrifice will be accepted by the gods until a man has his wife by

his side." And so it is that no yagna or puja is conducted without the

wife sitting to the left of the husband. Since then the wife is called vamangi,

she-who-sits-to-the-left.

With

Parvati by his side, Shiva made a declaration: "Let it be known, no

worship or sacrifice will be accepted by the gods until a man has his wife by

his side." And so it is that no yagna or puja is conducted without the

wife sitting to the left of the husband. Since then the wife is called vamangi,

she-who-sits-to-the-left.

He

said, "He who escapes from life's joys and sorrows, rather than dealing

with them, is a fool. He is running away from the Truth."

She

said, "He who is obsessed with the pleasures and pains of life, unable to

look at the serenity beyond them, is a fool. Even he is running away from the

Truth."

They

said, "Truth lies in harmony, harmony between matter and spirit, between

the body, mind and soul, between the individual and society, between society

and Nature, in purusha and prakriti."

Above the Clouds

Shiva

and Parvati travelled across the cosmos on the bull Nandi. In winter, they

wrapped themselves with soft tiger skins to keep out the cold. In summer, they

sought refuge from the harsh glare of the sun in the shade of trees. And when

dark rain-bearing clouds made their way towards the mountains, Shiva took

Parvati in his arms and carried her above the clouds, above the rain.

Parvati

was pleased with Shiva. She gave him a new name, jimutavahana,

he-who-rides-the-clouds.

Shiva's Dance

Parvati's

beauty inspired Shiva to create music and dance. From his melodious voice came

the musical notes and tunes that enchanted the entire cosmos. He created the

various dance elements gait, gestures, expression and posture that best

expressed human emotion. Shiva became lord of the arts, Kaleshvar.

Parvati's

beauty inspired Shiva to create music and dance. From his melodious voice came

the musical notes and tunes that enchanted the entire cosmos. He created the

various dance elements gait, gestures, expression and posture that best

expressed human emotion. Shiva became lord of the arts, Kaleshvar.

One

day, as Shiva danced, Parvati said, "Whatever he can do, I can do

beter." She imitated all his movements and her performance won the praise

of the gods. But then Shiva raised one of his legs and took the pose known as

urdhva-nataraja. Parvati refused to take this stance which she felt outraged

feminine modesty.

Shiva

brust out laughing and Parvati realised that he was just teasing her.

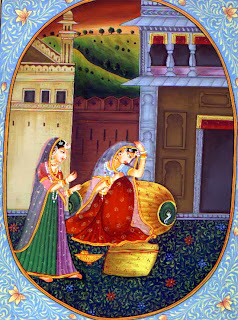

Game of Dice

Shiva

and Parvati often played dice atop Mount Kailas.

Once,

to make the game more exciting, Shiva offered to wager his trident, if Parvati

wagered her jewels. She did, but he lost. Then Shiva wagered his serpent, he

lost that too. Soon he had lost everything he possessed: his skull-bowl, his

rudraksha beads, his ash, his drum, his smoking pipe . . . and finally even his

loin cloth.

Humiliated

by this defeat, Shiva went into the deodar forest. Vishnu, feeling sorry for

Shiva, offered to help him out. "Play another game. This time I promise

you will win," he told Shiva.

And

that was exactly what happened. Shiva won back all that he had lost in earlier

games, even the loin cloth.

Parvati,

suspicious of Shiva's sudden success, called him a cheat. Shiva, outraged by

the accusation, demanded an apology. Words were exchanged, insults were hurled

. . .

Parvati,

suspicious of Shiva's sudden success, called him a cheat. Shiva, outraged by

the accusation, demanded an apology. Words were exchanged, insults were hurled

. . .

To

pacify them both, Vishnu appeared on the scene and revealed to Parvati the

secret of Shiva's victories. "My spirit entered the die. The dice moved

not according to your moves but according to my wish. So neither has Shiva

really won nor have you really lost. The game was an illusion; your quarrel a

product of delusion."

On

hearing Vishnu, Parvati and Shiva realised that life was like their game of

dice totally unpredictable and beyond control. They said, "Let the gods

bless all those who play dice on this day and realise this cosmic truth."

That day is Diwali, the festival of lights.

Annapoorna

Shiva

once told Parvati, "The world is an illusion. Nature is an illusion.

Matter is just a mirage, here one moment, gone the next. Even food is just

maya."

Parvati,

mother of all material things including food, lost her temper. "If I am

just an illusion, let's see how you and the rest of the world get along without

me," she said and disappeared from the world.

The

disappearance of Parvati caused havoc in the cosmos. Time stood still, seasons

did not change, the earth became barren ... there was a terrible drought. There

was no food to be found anywhere in the three worlds. Gods, demons and humans

suffered the pangs of hunger. They wept like children who seek their mothers.

"Salvation makes no sense to an empty stomach," cried the sages.

News

reached Shiva that Parvati had reappeared at Kashi and had set up a kitchen

there for the benefit of the world. He ran there as fast as he could, along

with every other hungry creature in the world. As he presented his bowl to her

he said, "Now I realise that the material world, like the spirit, cannot

be dismissed as an illusion."

News

reached Shiva that Parvati had reappeared at Kashi and had set up a kitchen

there for the benefit of the world. He ran there as fast as he could, along

with every other hungry creature in the world. As he presented his bowl to her

he said, "Now I realise that the material world, like the spirit, cannot

be dismissed as an illusion."

Parvati

smiled and fed Shiva with her own hands.

Since

then Parvati has come to be known as Annapoorna, the goddess of food. The image

of her serving food to her hermit-husband Train worshipped at Kashi, Varanasi,

in Uttar Pradesh. It is said she does not eat a morsel unless all her devotees

have been fed.

The Tribal Woman

Shiva

once got bored of married life. He went into the deodar forest to resume his

austerities. Unable to bear this separation, Parvati followed him there. But

Shiva took no notice of her.

"What

do I do now?" wondered Parvati. Vishnu whispered a solution in her ears.

Accordingly Parvati dressed up like a tribal-woman, bright beads round her

neck, peacock feathers in her hair. She sang and danced until Shiva could no

more ignore her.

"What

do I do now?" wondered Parvati. Vishnu whispered a solution in her ears.

Accordingly Parvati dressed up like a tribal-woman, bright beads round her

neck, peacock feathers in her hair. She sang and danced until Shiva could no

more ignore her.

Distracted,

he followed Parvati back to the romantic shores of lake Manasarovar. There,

inspired by Parvati's beauty, he picked up his lute, the rudra-vina and created

the most enchanting tunes ever heard in the cosmos.

Kali or Gauri

Once,

as sunlight streamed into their cave, Shiva looked at Parvati and laughed.

"You are so dark. You are Kali, the black one, black as coal, black as the

night sky, black as a crow, black as the pit of death."

Hurt

by Shiva's cruel words Parvati walked out of Kailas and moved into the deodar

forest. There she performed rigorous tapas. By the strength of her austerities

she shed her dark colour, which it is said percolated into the river Kalindi.

She became the radiant Gauri, as bright as a full moon and returned to Kailas.

Parvati,

as mother of the world and source of life, is called Gauri, bright and radiant,

full of hope. But when she becomes death, the final devourer of all things, she

is called Kali, the dark one from whom there is no escape.

Adi's Embrace

Shiva

never brought any gifts or food for Parvati. Sometimes he smoked narcotic drugs

in his chilum and ignored her for days on end. Once, tired of his callous

attitude, she ran into the deodar forest.

Shiva

never brought any gifts or food for Parvati. Sometimes he smoked narcotic drugs

in his chilum and ignored her for days on end. Once, tired of his callous

attitude, she ran into the deodar forest.

Taking

advantage of her absence, a demon called Adi entered Kailas and walked right

into Shiva's cave. The ganas did not stop him for he looked just like Parvati.

The demon had used his magic powers to bring about this transformation.

Adi

wanted to dupe Shiva. He was envious of the cosmic couple; he wanted to make a

fool of the great lord, humiliate him, mock his love for Parvati, and perhaps

even kill him at a vulnerable moment.

When

Shiva saw his beloved entering the cave he was delighted. He rushed to greet

her. But he soon divined the true identity and intention of this 'Parvati'.

Infuriated

by this deception Shiva became Ashani, the thunderbolt. His love turned into

rage, more terrible than lightning. He caught hold of Adi and sapped the

demon's life with his embrace. The gods cheered the destruction of the demon.

Days

passed. Parvati showed no sign of returning to Kailas. Her absence drove Shiva

mad. He began to dance wildly. The heavens trembled and the earth shook. Cracks

appeared on the foundations of the seas. Fearing the worst, the gods begged

Parvati to restrain her husband. Only she had the power to do that.

Parvati

returned to Kailas. As she walked up the hill singing songs of love, Shiva's

dance of sorrow turned into the dance of joy.

The

cosmos regained its balance, the world was safe and the gods were happy.

Parvati becomes a Fisherwoman

Shiva

and Parvati often discussed the secrets of the universe. Together they explored

the wonders of the cosmos.

Shiva

and Parvati often discussed the secrets of the universe. Together they explored

the wonders of the cosmos.

But

one day, as Shiva spoke to Parvati, he found her attention wavering. She was

looking at the fish swimming in the lake Manasarovar. "If fish is more

interesting than my words, I would rather you become a fisherwoman."

Parvati

obeyed Shiva and instantly took birth as a fisherman's daughter. She grew up to

be a strong and beautiful maiden. She oared her father's boat, mended his nets

and cleaned all the fish he caught. He was proud of her; his only worry was to

find a husband good enough for her.

Shiva

meanwhile, regretted his harsh words. From Kailas he looked at Parvati running

along the seashore and wondered how he could win her back. Manibhadra, Shiva's

faithful gana, saw his master's plight. He decided to do something to reunite

the lord with his beloved.

Taking

the form of a huge shark, Manibhadra began terrorising the sea coast near

Parvati's village. The fishermen didn't dare venture out into the sea. "It

broke our boats and tore up our nets. We are lucky to return alive," said

the men who survived its many attacks.

"He

who captures the shark will marry my daughter," declared Parvati's

fisherman father. Shiva immediately disguised himself as a young fisherman. Net

in hand, he sailed into the sea and captured the shark with ease.

Shiva

and Parvati were reunited. The fisherfolk celebrated their wedding in pomp and

style.

Parvati and Shiva isolate themselves

"I

don't understand," said Brahma looking at Shiva and Parvati, "At

times they are the loving couple, locked in embrace for seveal aeons, happy to

be with each other. Then, they fight, for as long and with the same intensity.

What is this great mystery?"

Vishnu

smiled. "You see the quarrels and the reconciliations between husband and

wife. I see the interactions between the cosmic spirit, purusha, and the cosmic

substance, prakriti. The relations of that divine couple reflect the ways of

the world; it oscillates the universe into life."

Once

Shiva and Parvati did not step out of their cave for a thousand years.

Impatient to meet their lord, the seven cosmic sages, the sapta rishis, walked

in without announcing themselves.

Parvati,

who was caught unawares, was so embarrassed that she picked up a lotus and

covered her face. The image of Parvati with a lotus over her face came to be

known as Lajjagauri, the-shy-Parvati.

Irritated

by this intrusion, Shiva and Parvati decided to isolate themselves. They moved

far into the inaccessible caves of the Himalayas. Some say, it was the cave at

Amarnath, Kashmir.

Here,

away from all interruptions and distractions, they explored the limits of

ecstasy. For the first time sensual pleasure, bhukti, became the tool of

spiritual emancipation, mukti.

Arousal of Kundalini

In

isolation, Shiva and Parvati let loose their full potential. Shiva stood on the

right as the fiery pingala. Parvati lay on the left as the frigid ida. By

various physical postures, asanas, mental exercises, dhyana and breath control,

pranayama, they balanced each other's energy until they were both in perfect

harmony, in a state of sushumna.

In

isolation, Shiva and Parvati let loose their full potential. Shiva stood on the

right as the fiery pingala. Parvati lay on the left as the frigid ida. By

various physical postures, asanas, mental exercises, dhyana and breath control,

pranayama, they balanced each other's energy until they were both in perfect

harmony, in a state of sushumna.

Parvati

was like a coiled serpent, kundalini, forming the base of the sushumna passage,

seeking union with Shiva. To that end, she began arousing herself with the five

makara tools: Bold diagrams, mandalas, appeared before her eyes. The sound of

chants, mantras, filled her ears. On her tongue was the rich taste of spiced

meat, mansa. Her nose was filled with the overwhelming scent of perfumes and alcohol,

madya. Her skin was stretched and awakened by many positions, mudra. She was

soon ready to rise.

Shiva

waited for her at the other end of the cosmos, at the complementary pole of

existence. While her senses were being excited, he stood beyond sensual

stimulations.

They

were two extremes of the cosmos she was water, he was fire; she was matter, he

was the spirit; she was the flesh, he was the soul; she was the senses, he was

the consciousness. She was in a state of agitation, he was calm; she was

Shakti, all the manifestations of energy, he was Shiva, pure, unadulterated by

any form or shape.

He

was Bhava, the eternal being; she was Bhavani, the eternal transformation. They

were ready to become one.

Parvati

uncoiled herself and rose through the sushumna, the very axis of existence. She

was like a dart, let loose by a strong bow. Her rise was spectacular: she

pierced six great cosmic nodes to reach her lord, it was the great

shat-chakra-bheda. She pierced the centres of fear, desire, hunger, emotion,

communication, introspection located in the body. These were the six chakras

which govern life: Muladhar, Svadhistana, Manipur, Anahata, Vishuddha and Ajna.

As

she pierced them, they bloomed like flowers, reaching their full potential. She

rose beyond the needs and demands of her physical existence. She crossed every

level of being and then joined her lord, the pure cosmic consciousness, in the

form of the thousand petaled lotus, the Saharsrapadma. He was the seed, the

jewel, mani, that she enclosed within her petals, padma.

Together

they returned to the time between creation, Om, and destruction, Hum. In that

state of dissolution, laya, beyond all opposites, there was just perfect bliss.

Man and woman became one, ardhanaranari, as the lotus of matter enclosed the

seed of the spirit.

Om

Mani Padamane Hum

Writer Name: Devdutt Pattanaik