The Epics

The Epics

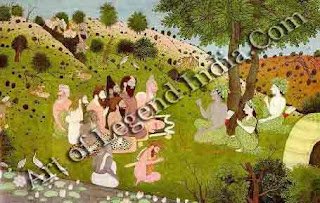

However,

since the ordinary people do not have the erudition to read and understand

these books, there are a third set of books, the Itihasas or Epics, which serve

the purpose. The profound philosophy of the Upanishads is presented in the form

of parables and stories in these epics for the guidance of the common people.

The

great epics of Hinduism are the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Yogavasishta and

the Harivamsa. They are also called the Suhrit Samhitas or friendly

compositions, as they teach the greatest of truths in an easy, friendly way

without taxing the mind, as the language is simple and the contents easily

understood.

Of

these the Ramayana and the Mahabharata are known even to the most illiterate of

Hindus as they have come down through the ages by word of mouth. They teach the

ideals of Hinduism in a most understandable form and it is because of these

books that the most illiterate of our peasants is not ignorant. On the other

hand he carries within him the wisdom of the Upanishads which has been conveyed

to him by these two major epics in story, ballad or dance form.

The

more popular of these two epics is the Ramayana. Also known as the Adi Kavya or

the first poetic composition of the world, it was written by the great sage,

Rishi Valmiki. In this epic is given the story of Rama, believed to be an

incarnation of Lord Vishnu, born on earth to show the path of righteousness.

Dasaratha,

king of Ayodhya, had four sons, Rama, born of his first queen, Kausalya.

Lakshmana and Shatrughna, born of his second queen, Sumitra and Bharata, born

of his favourite queen, Kaikeyi.

Dasaratha,

king of Ayodhya, had four sons, Rama, born of his first queen, Kausalya.

Lakshmana and Shatrughna, born of his second queen, Sumitra and Bharata, born

of his favourite queen, Kaikeyi.

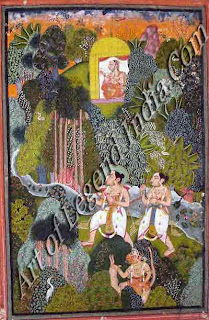

Rama

was banished to the forest for 14 years at the behest of his step-mother,

Kaikeyi, and left with his wife, Seeta, and brother, Lakshmana. In the forest

Seeta was abducted by the demon-king, Ravana of Lanka. Rama, helped by an army

of monkeys, and by Hanuman, the most loyal of them all, fought and destroyed

Ravana and brought back Seeta. He was then crowned king and ruled over Ayodhya.

Rama

Rajya, the reign of Rama, was one of idealism and 12 perfection, when no tear

was shed nor sorrow experienced. It was a time of peace and joy, an idyllic era

for all good people. Ayodhya became a land where tolerance and understanding

governed the actions of everyone and even the King's actions were subject to

the will of the people. Ideal behaviour of the rulers and ruled, of men and

women, were shown by the actions of the characters in this epic, thereby

teaching the people, subtly yet effectively, what ideal behaviour should be.

For

example, to show the qualities of ideal queens, we have Dasaratha's queens,

Kausalya and Sumitra, soft-spoken but strong, who placed the prestige of the

king and the kingdom above their love of their sons. Dasaratha had earlier

given two boons to Kaikeyi and she asked that Rama be sent to the forest for 14

years and her own son, Bharata, be crowned king. Rama, the ideal son, readily

agreed to go and Lakshmana accompanied him. Their mothers, Kausalya and

Sumitra, sent away their beloved sons to the forest so that king Dasaratha

could keep his word. A second lesson learnt from this was the importance of the

spoken word, especially the promises made by a ruler.

Also,

the sacrifices of which Hindu women were capable were depicted by several such

instances.

To

delineate the qualities of a high-principled man, we have Bharata who, on his

return from a visit to his uncle, found his brother banished to the forest by

his mother and the kingdom his to be ruled, as his father had died of grief

meanwhile. However he would not take over as king and, when Rama refused to

come back till all 14 years of exile promised by him to his late father and

step-mother were over, Bharata took his brother's paduka or wooden slippers,

placed them on the throne and ruled as regent till his brother's return.

The

qualities of the ideal man, prince and king are learnt by the ordinary people

to this day from the character of Rama, of the ideal woman and wife from the

strong but gentle character embodied in Seeta, and of the qualities of ideal

brothers from the behaviour of Bharata, Lakshmana and Shatrughna.

The

ideal qualities of loyalty, unstinted devotion and love are depicted in the

character of Hanuman, the monkey, who helped Rama cross over to Lanka and

defeat Ravana. When Lakshmana was hit by a poison arrow and needed medicinal

herbs from the Oshadhi Mountain in the Himalayas, Hanuman flew north all the

way but found, on reaching there, that he could not identify the particular

herb asked for. Knowing that his beloved Rama may not live if Lakshmana was not

revived, he lifted the whole mountain and carried it all the way back to Lanka.

The

potential for good and evil in all beings is brought out again and again. The

destruction of evil by good either by oneself or by divine intervention is a

constant theme of Hinduism.

Even

the demons were not all bad and wicked and are shown as having good qualities

also. Ravana, the demon-king of Lanka, was a great scholar. Even though he

abducted Seeta to make her his queen, he treated her with respect and regard

and never molested or harmed her but awaited her consent to marry her. Hanuman,

in his attempt to locate Seeta, visits Lanka, and is greatly struck by Ravana

and says, "What courage! What strength! What a combination of great

qualities is Ravana!"

Even

the demons were not all bad and wicked and are shown as having good qualities

also. Ravana, the demon-king of Lanka, was a great scholar. Even though he

abducted Seeta to make her his queen, he treated her with respect and regard

and never molested or harmed her but awaited her consent to marry her. Hanuman,

in his attempt to locate Seeta, visits Lanka, and is greatly struck by Ravana

and says, "What courage! What strength! What a combination of great

qualities is Ravana!"

Ravana's

brother, the demon Kumbhakarna, disapproved strongly of the abduction of Seeta.

Yet because he had prospered under Ravana's patronage, and "eaten his

salt", he refused to desert his brother in his hour of peril.

The

great virtue of loyalty, even for a lost cause, was brought out by such

instances.

Through

the stories from the Ramayana which are recited to them, the ordinary people

learn the difference between right and wrong, develop a high sense of values

and understand what ideal behaviour is. The tremendous cultural heritage of the

Vedas and Upanishads has reached and permeated to the most illiterate of our

people through Sage Valmiki's priceless epic, the Ramayana. This is why our

peasants, even those living in remote villages, know to this day what they can

expect from the laws of the land and are not ignorant of their rights nor of

what is due to the ruled by the rulers. The illiterate peasant trusts his

rulers implicitly, expecting another Rama Rajya, and today uses the modern tool

of the vote to express his feelings towards his rulers. The illiterate villager

is therefore not ignorant as the city educated think him to be.

The

second great epic of the Hindus, the Mahabharata, was compiled by Sage Vyasa

and revolves around the Great War between two princely families, the righteous

five Pandava brothers and their evil cousins, the hundred Kauravas. The central

character of the epic is Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu on earth, a man

of action and statesman.

The

second great epic of the Hindus, the Mahabharata, was compiled by Sage Vyasa

and revolves around the Great War between two princely families, the righteous

five Pandava brothers and their evil cousins, the hundred Kauravas. The central

character of the epic is Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu on earth, a man

of action and statesman.

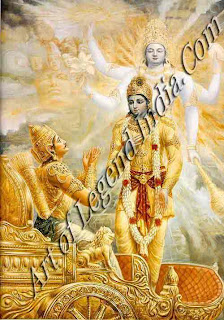

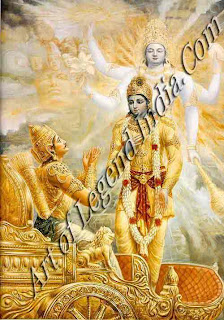

When

poised on the battlefield ready for battle, Arjuna, the great warrior and one

of the Pandava brothers, sees that the enemies that are arrayed before him are

his close relations, cousins, uncles and grand-uncles, and refuses to fight or

destroy them. Krishna, who acts as his charioteer, advises him on the

importance of his dharma or duty as a warrior to fight for righteousness. The

Kauravas, representing evil, have to be destroyed to restore Dharma or

righteousness in the land.

Swami

Vivekananda compares the Kurukshetra battlefield to the world we live in. The

five Pandava brothers represent righteousness and the hundred Kauravas the

myriad worldly attachments we have to fight against. Arjuna, the soul awakened

by the teachings of Krishna, is the general who leads in this battle.

The

teachings of Lord Krishna called the Bhagavad Gita, or the Song of the Lord,

are part of the discourse between Lord Krishna and Arjuna at Kurukshetra during

the great Mahabharata War. In this priceless scripture, Lord Krishna places

emphasis on Nishkama Karma or action without desire or passion and without any

worry about the fruits or results of one's actions. Through such scriptures the

duties of the ideal man were laid down, showing him to be a Yogi, or one

unattached to worldly desires, as far as his heart and mind are concerned, but

also as a man of action setting right the wrongs of society.

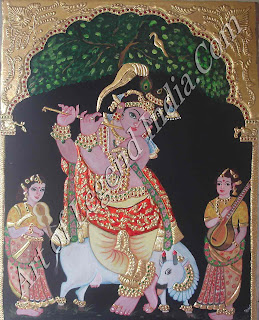

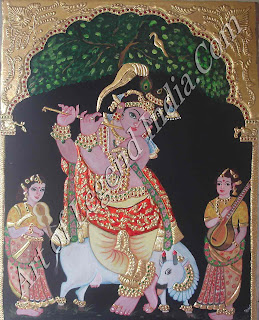

An

interesting allegory is the comparison of the Upanishads to a cow, the Bhagavad

Gita to milk, Krishna to a cowherd and Arjuna to a calf. In other words, the

essence of the Upanishads is milked by Krishna and the milk, the Bhagavad Gita,

fed to Ariuna.

An

interesting allegory is the comparison of the Upanishads to a cow, the Bhagavad

Gita to milk, Krishna to a cowherd and Arjuna to a calf. In other words, the

essence of the Upanishads is milked by Krishna and the milk, the Bhagavad Gita,

fed to Ariuna.

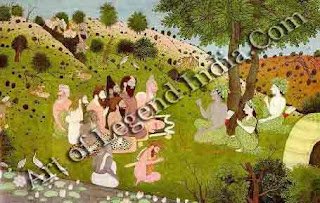

The

Shantiparva of the Mahabharata contains the teachings of Bhishma Pitamaha, the

grand-uncle of the family from which were descended both the Pandavas and the

Kauravas. These words of wisdom were uttered while Bhishma was awaiting his

death after being seriously wounded in the Great War. In his discourse, Bhishma

instructs Yudhishtira, the oldest Pandava brother, on Dharma or righteous

conduct and duty, on statecraft and the responsibilities of a ruler. These

teachings on Hindu Dharma are without parallel.

From

the Mahabharata, therefore, the people learnt the rules and the codes of ideal

conduct laid down for man and woman, king and commoner.

Writer –

Shakunthala Jagannathan

The Epics

The Epics  Dasaratha,

king of Ayodhya, had four sons, Rama, born of his first queen, Kausalya.

Lakshmana and Shatrughna, born of his second queen, Sumitra and Bharata, born

of his favourite queen, Kaikeyi.

Dasaratha,

king of Ayodhya, had four sons, Rama, born of his first queen, Kausalya.

Lakshmana and Shatrughna, born of his second queen, Sumitra and Bharata, born

of his favourite queen, Kaikeyi.  Even

the demons were not all bad and wicked and are shown as having good qualities

also. Ravana, the demon-king of Lanka, was a great scholar. Even though he

abducted Seeta to make her his queen, he treated her with respect and regard

and never molested or harmed her but awaited her consent to marry her. Hanuman,

in his attempt to locate Seeta, visits Lanka, and is greatly struck by Ravana

and says, "What courage! What strength! What a combination of great

qualities is Ravana!"

Even

the demons were not all bad and wicked and are shown as having good qualities

also. Ravana, the demon-king of Lanka, was a great scholar. Even though he

abducted Seeta to make her his queen, he treated her with respect and regard

and never molested or harmed her but awaited her consent to marry her. Hanuman,

in his attempt to locate Seeta, visits Lanka, and is greatly struck by Ravana

and says, "What courage! What strength! What a combination of great

qualities is Ravana!"  The

second great epic of the Hindus, the Mahabharata, was compiled by Sage Vyasa

and revolves around the Great War between two princely families, the righteous

five Pandava brothers and their evil cousins, the hundred Kauravas. The central

character of the epic is Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu on earth, a man

of action and statesman.

The

second great epic of the Hindus, the Mahabharata, was compiled by Sage Vyasa

and revolves around the Great War between two princely families, the righteous

five Pandava brothers and their evil cousins, the hundred Kauravas. The central

character of the epic is Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu on earth, a man

of action and statesman.  An

interesting allegory is the comparison of the Upanishads to a cow, the Bhagavad

Gita to milk, Krishna to a cowherd and Arjuna to a calf. In other words, the

essence of the Upanishads is milked by Krishna and the milk, the Bhagavad Gita,

fed to Ariuna.

An

interesting allegory is the comparison of the Upanishads to a cow, the Bhagavad

Gita to milk, Krishna to a cowherd and Arjuna to a calf. In other words, the

essence of the Upanishads is milked by Krishna and the milk, the Bhagavad Gita,

fed to Ariuna.

0 Response to "The Epics of Hinduism - Mahabharata"

Post a Comment