If you look at the map of the

world you will not find the village of Madhubani on it. Even if you can trace

the contours of the saried woman, which is the shape of Bharat Mata, you will

not find the beautiful mole on her face called Madhubani. But if you translate

the word Madhubani, you will soon know where it could be. The forest of honey,

which is the literal meaning of the name of the village, could be anywhere in

the vast landscape of our subcontinent.

If you look at the map of the

world you will not find the village of Madhubani on it. Even if you can trace

the contours of the saried woman, which is the shape of Bharat Mata, you will

not find the beautiful mole on her face called Madhubani. But if you translate

the word Madhubani, you will soon know where it could be. The forest of honey,

which is the literal meaning of the name of the village, could be anywhere in

the vast landscape of our subcontinent.

Certainly, it was a very apt

name in the olden days, when the greater part of our earth was full of dense

jungles, in which the folk made little clearings and settled down in the

eternal world of birth and rebirth, so they believed, according to their Karma,

of good or bad deeds in the past life. The poetical myth, which is enshrined in

the name of Madhubani may have been based on reality. In the trees of the

forests near the village, the bees may have made beehives. The people may have

gathered these hives and extracted from them the honey to sweeten their own

lives and those of others. In the feudal centuries, there were terrible

hardships in growing grain on small portions of land, with the wooden plough,

in good weather and bad. Green harvests depended on the will of the gods. The

honey may have been a constant source of happiness. And, in their innocence,

they seized upon the perennial source of pleasure as the name of their hamlet.

The innocence, which seems to

be obvious in naming the village, is also revealed in the traditional character

of the folk of Madhubani. It may have come from a dim sense of the revelation

of things from the obscure areas of the heart. This is the way in which men and

women become aware of nature, as mother, hear echoes of the emotions they feel,

which they put into words to signify the phenomena around them, so that the

obscure feelings about the verdant earth, the sun, the moon and the stars, the

flora and fauna, may become manifest to them.

But before they pronounce words

they make images of their myths, dreams and fantasies. The myth of the name of

Madhubani is one of the many fables through which the folk here, as elsewhere,

have connected themselves with the cosmos. Some of these legends were invented

by the local bards, but many of them were inherited from forefathers, and are

part of the oral culture of our peoples, only varied somewhat in the telling,

by the salt of the tongue of the teller.

Actually Madhubani has now

become a market town and the village where most of the painters continue to

paint is Jitwanpur, about three miles away.

Surrounded by mango and banana

groves, the hamlet is outwardly just a typical north Bihar cluster of thatched

huts beyond a green pond in which some buffaloes are cooling themselves, while

children try to goad them out with little bamboo sticks.

Squatting on the cow dung

plastered floors of their houses, some women daily paint pictures, under the

shadow of the walls which they painted long ago.

In this and a few other hamlets

they have been doing this ritual colour work for generations.

The primary myth about the

origin of the world is known to every Hindu villager in Bharat. The Great God,

Brahma, was filled with the desire to play. In this mood he played hide and

seek with his consort Lakshmi, loved her and created the whole world. So the

universe is the soul and body of the Great God.

The early myths of the Rigveda

in which the Aryan ancestors had enshrined their poetical reactions, to the

surroundings in which they found themselves, have been passed on by word of

mouth, by father to son, and mother to daughter, for generations. As the

Gayatri hymn to the Sun has been sung for centuries on the banks of the Ganga,

not only during festivals, but every morning and every day, Surya has been

worshipped through prayers, and also by the way in which the eyes bend down

before the refulgent Sun, over joined hands, when Surya appears at dawn to give

light, and before he departs into the twilight of the evening. The dawn is an

experience for every peasant, who begins the ritual of everyday life by going

out into the fields and to the river for his ablutions before sunrise. The god

of thunder and lightning, Indra, is welcomed after long months of the parching

summer. The moon is watched as it matures from the crescent into the full round

shining face of Poornamasi, when the folk dance to celebrate the heightening of

the nights to the splendour of golden light.

In this ritual, the aspiration

to the connection with the gods becomes a vague sense of connection with the

Supreme God from whom men and women are separated. And meditation on the

pictures connects.

This urge for connection, for

absorption, and salvation, became the curve of the inner journey towards the

Self through the outward strayings in the mundane world.

This urge for connection, for

absorption, and salvation, became the curve of the inner journey towards the

Self through the outward strayings in the mundane world.

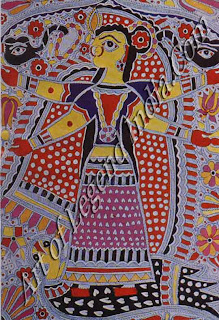

Even before the ardent

stirrings in the soul of the Vedic poets, our primitive ancestors had looked

for protection to the mother, and there had been evolved the myth of Saranyu,

daughter of Tavstar, the god who made the cosmos and all loving things. In the

Rigveda she appears as the Goddess who moved at great speed, rushing out of the

creator into existence, but going back again to the gods. The name Saranyu

means she who runs. She is the pristine goddess, the primary power, who once

assumed human shape and became incarnate in other forms. The images of the

mother goddess include: Sarama, Saraswati (the mighty river which went

underground); Vak the goddess who sings of herself; Aditi the boundless sky,

air, mother and father and essence of all the gods and goddesses, the five

kinds of being that are born and will be born; the auspicious Lakshmi giving

wealth, the lotus-born standing in the lotus, lotus-eyed, abounding in lotuses;

Usha, the dawn, the virgin daughter of heaven; Durga, the gracious mother;

Kali, the dark flame of fire who consumes the world and existence; and Devi,

who takes the innumerable shapes and gives grace to all worshippers.

The mother goddess, in all her

exalted incarnations, was worshipped by the folk as a fertility image, as the

naked woman with the emphatic pudenda, shown squatting almost in the act of

giving birth.

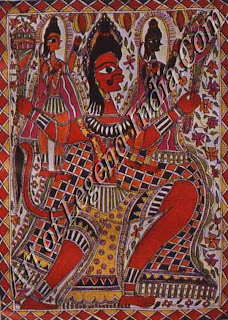

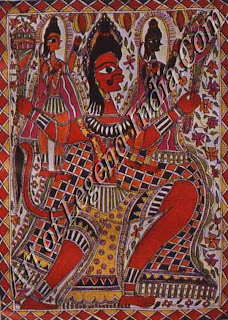

The mythical stories of the

heroes and heroines of the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata were also inherited

by the folk in Madhubani, through the recitation of these narratives during the

yearly festivals.

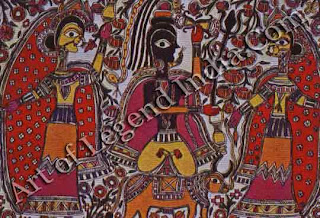

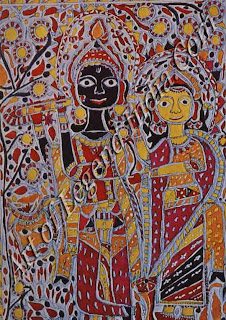

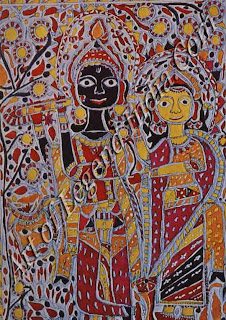

Apart from Rama and Sita, the

ideal pair, whose devotion to each other became the symbol of devotion between

husband and wife, the hero-god Krishna seems to have been adored in Eastern

India, specially as the twelfth century Mithila poet, jayadeva, celebrated the

amours of this love god with his consort, Radha, in his Gita Govinda.

The various tales retold in the

Puranas, or old books, rendering old stories, became part of the inheritance

and fulfilled the desires of many peoples in different ways.

I take the forms desired by my

worshippers,' Krishna said in the Bhagavad Gita. And there was always an answer

in some vital story or the other, to the urge for alliance with the gods,

against the dangers, the in clemencies of weather, and the forces of evil and

death which may end life.

As the feelings, urges and

stirrings towards security, longevity and prosperity, by alliance with spirits,

were the curves of desire, but could not be easily fixed in words, so images in

clay, in wood, stone and colour began to be made by the folk to define the

contours of the wished for spirits. And these figures were often sanctified by

prayers and the god or goddess incarnated in the material shapes and

worshipped.

The child, or the primitive,

creates an image in the likeness of what he or she wishes to become. Words are

vague. They only affect the soul where they are rhythmically intoned or

rhetorically delivered by an orator, or breathed in magical whispers by a

priest into the ear as Sruti, inspired by God. Images are more precise because

they are concrete. They picture vibrant feelings, metaphors and recreate myths,

so that we may remember the shape, size and texture of the spirit which has

hovered over the head, or is moving about in the soul, as a fleeting feeling.

When made and put on the mandala and holified by puja, the image as icon

affords the worshipper rest in the symbol, against the torment of not being

able to connect with a god or goddess through changing emotions. For instance,

once the imagination, recalling the memory of thunder and lightning, has

conceived the image of the God Indra driving his chariot across the sky, so

fast that the wheels create terrible sounds and spread sparks of fire, the

spirit of this dynamic god becomes incarnate on a wall when drawn as a concrete

expression.

The child, or the primitive,

creates an image in the likeness of what he or she wishes to become. Words are

vague. They only affect the soul where they are rhythmically intoned or

rhetorically delivered by an orator, or breathed in magical whispers by a

priest into the ear as Sruti, inspired by God. Images are more precise because

they are concrete. They picture vibrant feelings, metaphors and recreate myths,

so that we may remember the shape, size and texture of the spirit which has

hovered over the head, or is moving about in the soul, as a fleeting feeling.

When made and put on the mandala and holified by puja, the image as icon

affords the worshipper rest in the symbol, against the torment of not being

able to connect with a god or goddess through changing emotions. For instance,

once the imagination, recalling the memory of thunder and lightning, has

conceived the image of the God Indra driving his chariot across the sky, so

fast that the wheels create terrible sounds and spread sparks of fire, the

spirit of this dynamic god becomes incarnate on a wall when drawn as a concrete

expression.

And, then, He is not a mere

sound of the rhetorical flourish of a hymn in the Rigveda, but the certainty of

the divine presence, liberating the devotee, through expression, or the making

of the picture, from the dread of the bursting sky with its loud crackling

sounds and its piercing shafts of fire. The religious icon is, therefore, the

complement of the poetical metaphor. The first language of the naive mind is in

images, which are magical shapes that evoke the protective spirit when beckoned

in meditation.

The art of Madhubani is thus

mythology. Not art in the sense of 'significant form' of the West. The

paintings are legends to which the folk turn to pray in the daily ritual.

The feeling, or energy, or emotion,

or invisible stirring, is sought to be imaged as a vital flourish of lines and

colours which enshrines the powers of the divinity and can be contemplated with

a view to receiving those vitalities into oneself. In fact, the whole basis of

Indian creativeness seems to have been to evolve images through which the

worshiper desires to become god or goddess.

This kind of transformation of

human beings into gods and spirits and demons through idols has, in fact, been

the source of all achievements in the arts of the refulgent genius of Indian

peoples.

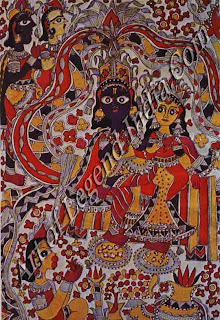

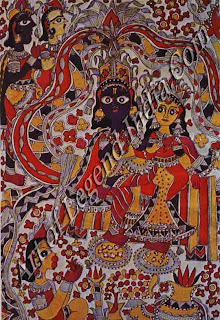

The underlying idea of seeking

alliance with the image, is enacted as a drama in a festival like Durga Puja.

The images of the Goddess are made by the female folk or by the local

craftsmen. They are worshipped during the special festivals, at a particular

time of the year. The powers of the goddess are sought to be absorbed in one's

own inner life through worship. And then the image is thrown into the river, so

that it may become part of the cosmos, to be made again the next year, but

leaving the residue of the feeling of its force in the worshipper, so that he

or she can turn inwards and recall the image at will. The intention behind the

ritualistic use of the icon made the whole tradition of the art of India

possible. Every idol is for contemplation, in a dhyanamantra, or is meant to

evoke the vision of a concrete divinity, by seeking whose powers, in the

grooves of one's person, the awareness of the worshipper can extend itself

beyond the everyday round, and thus acquire ineffable devotion to the higher

self which may be exteriorised.

The underlying idea of seeking

alliance with the image, is enacted as a drama in a festival like Durga Puja.

The images of the Goddess are made by the female folk or by the local

craftsmen. They are worshipped during the special festivals, at a particular

time of the year. The powers of the goddess are sought to be absorbed in one's

own inner life through worship. And then the image is thrown into the river, so

that it may become part of the cosmos, to be made again the next year, but

leaving the residue of the feeling of its force in the worshipper, so that he

or she can turn inwards and recall the image at will. The intention behind the

ritualistic use of the icon made the whole tradition of the art of India

possible. Every idol is for contemplation, in a dhyanamantra, or is meant to

evoke the vision of a concrete divinity, by seeking whose powers, in the

grooves of one's person, the awareness of the worshipper can extend itself

beyond the everyday round, and thus acquire ineffable devotion to the higher

self which may be exteriorised.

This kind of contemplation of a

ritual image is quite different from looking at a work of art in the West,

except in the early Christian art, where the holy figures were placed in church

for bent-head reverence. These images were quite different from the pictures of

the Renaissance art. Thus Raphael's Venus, modelled on a beautifully

proportioned human female, is supposed to invoke, in the onlooker, the sensuous

sense of her chiselled face, her gracious bent neck, volumes of the breasts and

the excitations of the naked belly, the shapely hips and legs, as aesthetic

delight. There is no doubt that the vision of Venus uplifts the spectator.

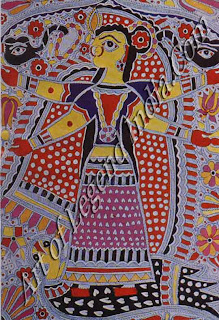

But the dramatic composition of

Durga, as Mahismardini, showing her slaying the buffalo demon, is supposed to

suggest the fight of good against evil, revealing also the power of the

goddess, in all the intensity of her destructive force, to ally the worshipper

with the protective mother, devotion to whom would quell all those forces which

are inimical to life.

If the naturalistic form of

Venus arouses mainly the senses, the vision which is behind the creation,

destruction and preservation of the world is supposed to be part of the creative

intuition of Hindu ritualistic-art-expression in the Mahismardini image of

Durga.

We cannot, therefore, equate

the rasa, or flavour, which seeps into the devotee, with the aesthetic delight

which is the ideal of Western art, though rasa includes appreciation of forms.

But it denotes more comprehensive appreciation than the aesthetic term of Clive

Bell's 'significant form'.

We cannot, therefore, equate

the rasa, or flavour, which seeps into the devotee, with the aesthetic delight

which is the ideal of Western art, though rasa includes appreciation of forms.

But it denotes more comprehensive appreciation than the aesthetic term of Clive

Bell's 'significant form'.

The creative energies in every

work of art, in India, until the end of the mediaeval period, and in rural

India until now, were dedicated to self creation, self-perpetuation and

self-expression, as a part of the process of increasing awareness and thus to

attain insights and heighten consciousness.

As Brahma had created the

world, so every human being recreates his or her life, every day of the year.

This recreation takes the form

of exalting the house above the decay of the previous day.

The dwelling is swept clean and

plastered with the sacred cow dung wash. The rice powder drawing of flowers

called alpona is traced by the hand on the threshold, by the mother of the

family, the creator, before anyone wakes up.

The water of a holy river or

stream is brought and sprinkled all over the house, or the Ganges water,

fetched on the last pilgrimage to the mother Ganga, is sprinkled to purify the

precincts.

The flowers, which have been

brought from the fields, are put before the mandala, on which the favourite

gods are arranged in images of stone, metal, or on paper.

The puja or meditational

prayer, is then performed by all the members of the family, together or apart.

The incense or dhoop is taken

around the house to all the corners, to smoke the evil spirits away.

The first portion of food is

sent to the temple for the gods before the family is served the meal.

Almost every act is made holy

by the frequent remembrance of the favourite God's name.

In everything, then the

empirical Self is related to the higher self. The dream of every man or a woman

is to rise above the earthly condition and become a god or a goddess. The family

had already exalted every child, male or female, to the status of divinity, by

naming the young after the celestials. A boy would be called Shiv Shankar,

Krishan Lal or Vishnu Dayal. A girl would be called Savitri Devi, Lakshmi Devi

or Parvati Devi.

This exaltation of the human

self is integral to all cultures. In almost every part of the world, in all

societies, some form of magic making, which is a poetical faculty, has been

current. The pantheistic tendency to ascribe a soul to a tree, a bird, a river,

a mountain, or a house, can be seen in the most primitive societies.

In India the daily self was

reminded every day by the sloka of the Upanishads:

- Whence

are we born?

- Whereby

do we live??

- On what are we established??? Under whose

orders do we suffer pains and pleasures?

- For

obviously the ego is not a free agent

- Being

under the sway of happiness and misery

This questioning was literally

adopted by custom by the folk. Because it was to give a jolt from the habitual

life to every person, so that he or she may wonder why we are here and not

there, why we were born at all, and who put us here.

The earliest hunches had a

vague sense of an omnipotent creator, so the path of meditation was advised by

the priest to attain atma-shakti, the cosmic power of the Supreme God, the one

cause of all the causes, through the appreciation of the qualities which the

creator had imbued in all his creation. To rise from the lowest essence of

tamask or crudeness, to rajask or heightening, and satvas or truth, is to emerge

from the attachments of the lower life of ignorance, avidya, to illumination,

above the decay, to those subtle areas which are beyond the threshold of

consciousness.

The tendency to be attached to

the world of dailiness, of samsara, has to be got over by discarding the

standardised reflections, abhasa, and transcend to the mystery of being, by

putting before oneself the image of the god into whose particular incarnation

one may aspire to.

In the pursuit of the authentic

life, as against the unauthentic habitual existence, everything has to remind

the individual of the model of the grace of Vishnu, or the elemental force of

Shiva, or the love of Devi.

As the spiritual presence which

human beings seek is hidden behind everything, the sense of wonder has to be

kept alive and rahasya, or the mystery, revealed. The realisation of the

mystery may elevate one to ananda or transcendent bliss.

The painting of the forms of

God's creation, or image-making thus become part of a way of life.

The ritual painting is a simple

process. Certain symbols had been handed down by tradition. The recreation of

those in the alpana of the threshold or on the walls has been repeated day

after day without much variation. Perhaps on a festival, the grandmother of the

family, or the older aunt, may bring out, from the welter of images, a memory

image from her own youth in another village. The form of some flowers, or the

vessel in which the flowers are put, may thus become a variation on the old

theme.

The ritual painting is a simple

process. Certain symbols had been handed down by tradition. The recreation of

those in the alpana of the threshold or on the walls has been repeated day

after day without much variation. Perhaps on a festival, the grandmother of the

family, or the older aunt, may bring out, from the welter of images, a memory

image from her own youth in another village. The form of some flowers, or the

vessel in which the flowers are put, may thus become a variation on the old

theme.

Occasionally, an individual

talent may arise, like the now legendary Sita Devi, a Brahmin widow of three

score and seven, who began scribbling in her girlhood. sShe might have been the

odd woman out, who dared to dramatise certain forms, was perhaps emboldened,

mischievously, to caricature Hanuman, to emphasise his powers and transgress

the norms of the routine drawing, with brighter earth colours. She and her

youthful companions must have gone to the village fairs, across miles of

ploughed fields, along dusty roads to the riverside.

They had sung songs, as they

bore the effigies they made of the goddess, after weeks of worship, and then

threw them into the Mother Ganga. In the fair were the toys shops, selling

images of the gods, and birds and animals, made by village potters, which may

have come back as echoes. Then they would have been the itinerant players,

enacting the yatra the rural theatrical performance, singing the story of the

Ramayana, or the tale from the Mahabharata. And she and her own family would

have come back singing songs on the journey back home.

The impressions of the faces of

the brides, taken by the mothers-in-law to the fair, would have emerged in the

hand of Sita Devi, as the heroine Sita and Rama would be dramatisation of her

own husband in the painting she would make.

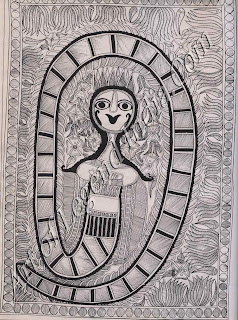

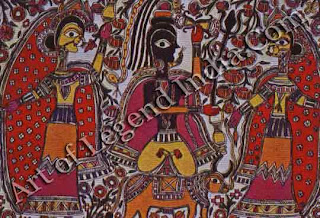

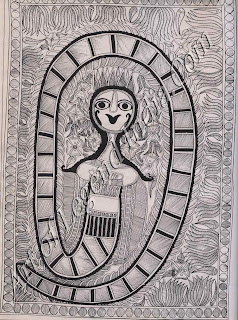

In talking to Sita Devi, I

found that she is a natural naive painter, who has observed the malleable faces

of the performers in the yatra, their movements and stances and their tableaux.

Her hands move quickly around the circle of sun. She is so fluent in her

drawing of curves that she goes on from rounder to rounder. Equally easily, she

radiates from the orb little edges of rays, which she slowly embellishes with

delicate lines into flower beds. Or she goes to connect the sun-faces, already

emergent, with big eyes, and a sacred red mark on the forehead, to symbolic

squares for drapery. And then she creates a little universe of lotuses, flame

flowers, and peacocks dancing in the garden. One can notice that her dynamic

fingers have a natural sense of design. Her eyes are concentrated. And she has

immense patience with the minor lines and points, in the morphology of

pontillism, which is her unique contribution to the composition. And the

binding lines are energised beyond the prototypes.

The impression she gives is

that her body-soul creation, is an original rhythm which she has initiated, a

unique of Madhubani style of her own.

In so far as the forms

recreated by Sita Devi are new beginnings of multiple relations of rounds,

squares, triangles, and rhythmic binding lines, in overall patterns, we are

struck by the pictures as novelties above the stereotypes.

There are other creative

talents in Jitwanpur. In fact, almost every second person in a family paints.

There are other creative

talents in Jitwanpur. In fact, almost every second person in a family paints.

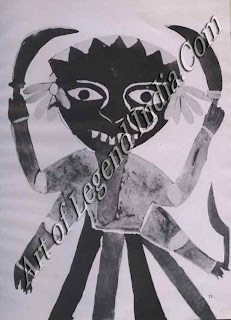

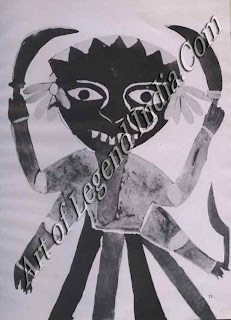

Surya Dev, the son of Sita

Devi, learnt from his mother, first by filling in the outlines of her drawings

with colours. Since then he has developed a fluent line and can do even large

scale paintings. He absorbs impressions from outside Jitwanpur and says he

prefers the torried glare of the day, to the night when the monsters of the

dark swarm around. He is conscious that he comes from a family of priests who

used to perform death ceremonies. Yama is everywhere, he whispers, and must be

driven away with all his doots.

A nearby neighbour, Bana Devi

paints surrounded by children. Two young girls help her, learning from the

elders as in the past. The littlest ones are given paper and colours to play

with. They are luckier than Bana Devi, who was married at the age of five and

was a maid-of-all-work until she matured and began to earn money with her

paintings. Shyly covering her demure round face, she concentrates on a smiling

moustached sun, obviously an ambivalent symbol of happiness itself, the

protective father image.

A perceptive collector

discovered some Harijan painters. In the pictures of these 'lower' peoples, the

deities and the victims coincide.

All the painters are aware that

the loving adoration of the preferred spirits liberates them through the

recreation of the traditional myth as a personal myth. Besides, there are the

incipient urges to rise above the dailiness of ploughing, washing, cooking and

doing the chores, in the seemingly changeless samsara, to authentic life of the

future from the urgency to be immortal.

In the deeper layers of such

creativeness, is the intent to offer the sacrifice of one's self to the gods.

It is conceivable that though the ancient Aryan Yajnas or self sacrificial

ceremonies by burning clarified butter, so that the heat of the passion should

rise to the heavens and the earth be purified.

In the deeper layers of such

creativeness, is the intent to offer the sacrifice of one's self to the gods.

It is conceivable that though the ancient Aryan Yajnas or self sacrificial

ceremonies by burning clarified butter, so that the heat of the passion should

rise to the heavens and the earth be purified.

Racial memory gave place to

image worship. The instinctive urge to go to pray was transformed into the

struggle to beckon the gods. And the energies of the body-soul were sacrificed

in the magical act of drawing, painting or sculpting.

This struggle to invoke the

spirits seems to have become a racial characteristic. Not only the Brahmin

members of the hierarchy paint pictures in Madhubani, but the people of the

lowest caste, also indulge in such symbolic expressionism.

And, curiously, the same family

gods and goddesses appear in Harijan paintings as in the free-hand work of the

'twice born'. The sameness of the theme confirms the process of hieratic art,

as also it emphasises the notion that the Harijans are also offering prayer and

sacrifice as part of the fourfold Hindu order, even though they are considered

beyond the pale, because of the menial work which is their function.

Actually, if we go to the

sources of creativeness in our civilisation, we find that the gods and

goddesses being our own higher incarnations and near neighbours, the invocation

of them is a purely human act, subject to no other law, except the vitality of

the rhythmic impulse which creates forms in different proportions, contours,

with emphasis on colours according to the individual talent of the painter.

Actually, if we go to the

sources of creativeness in our civilisation, we find that the gods and

goddesses being our own higher incarnations and near neighbours, the invocation

of them is a purely human act, subject to no other law, except the vitality of

the rhythmic impulse which creates forms in different proportions, contours,

with emphasis on colours according to the individual talent of the painter.

Thus though the family gods are

the same, because of mythical contours of divinities are fixed, the forms by

the 'upper' hierarchy are thinner and the colours of the 'lower' peoples are

thicker. The lines of the former are more curved, while sharp triangular lines

are visible along with roundings in the latter. The Brahmin paintings tend to

be decorative, while the Harijan works are more expressionist and passionate.

If on the surface the symbols

of both strains are similar, the thickening of tones in the works of the

Harijans imparts a certain vitalism to their compositions. The dark necessities

from which thick paints are imparted seem to inspire in men and women, urges

towards freedom of action beyond the oppression of millenniums. It seems that

each God forgotten by the God-forsaken is being recalled, in all innocence,

perchance He may deliver the Harijans by the renewal of their faith in Him.

In every creation of man there

is implicit the ambiguity of the relationship between the originator and his

work. While the painter may be revealing the mysterious idol in a recognisable

shape, the bent of his own empathy turns or twists the forms.

Unlike other folk of other

areas, the Madhubani painters, both Brahmins and Harijans, venture into the

realm of the gods, to dissolve their fears in the continuous resurgence of the

hope of receiving from the beneficent holies, for their body-souls, a certain

depth in which may be resolved the daily predicament of being-in-this-world

situation.

Unlike other folk of other

areas, the Madhubani painters, both Brahmins and Harijans, venture into the

realm of the gods, to dissolve their fears in the continuous resurgence of the

hope of receiving from the beneficent holies, for their body-souls, a certain

depth in which may be resolved the daily predicament of being-in-this-world

situation.

If the creations of the

craftsmen of the courts lapsed, because there was no patronage left after the

alien impacts, the arts of everyday life of the folk have, fortunately,

survived wherever the myths of a faith are sung or recited or enacted in

dance-dramas.

This organic relationship

between the performing arts and the visual expression in images must be noticed

as an important departure point in the making of images. In eastern India and

in Rajasthan scrolls were taken in procession and unfolded before the folk with

the myth or legend recited.

The core of the relationship is

in the connection with the old symbols, which die from repetition and must be

made alive, to appease the makers and the onlookers, through the battlements,

the miseries and the challenges of the daily life. The personal recollection of

a moral tale is, indeed, a repetition of an eternal human attitude, accepted in

uncritical, blind worship, in answer to every baffling new situation. But the

drums and cymbals renew the memory and make for the warmth of a living

connection between the worshipper and the god, even in the shells of the old

fables.

The folk in a village find that

they have to survive in the hamlet on their own mental and physical resources.

Some of the questions of the daily life have been answered in the recitals. All

the desires, emotions, frustrations, aspirations, lusts, greeds, jealousies,

have been expiated in the myths about the gods, who were originally based on

heroes or exalted fantasies of behavior, which were models of angels against

the evil demons. And behind the gods, there is lurking, always, the Supreme

God, the exalted, the unreachable, the impenetrable, who has inspired the

essence of the good, the beautiful and truthful in all creatures from which

they can hark back in yearnings and desire, which become myth, and which are

the means of reaching him in moments of ecstasy that is to say in being

oneself.

The folk in a village find that

they have to survive in the hamlet on their own mental and physical resources.

Some of the questions of the daily life have been answered in the recitals. All

the desires, emotions, frustrations, aspirations, lusts, greeds, jealousies,

have been expiated in the myths about the gods, who were originally based on

heroes or exalted fantasies of behavior, which were models of angels against

the evil demons. And behind the gods, there is lurking, always, the Supreme

God, the exalted, the unreachable, the impenetrable, who has inspired the

essence of the good, the beautiful and truthful in all creatures from which

they can hark back in yearnings and desire, which become myth, and which are

the means of reaching him in moments of ecstasy that is to say in being

oneself.

The sources of folk art of

Madhubani lie on the dim areas of silence, of the approximation to the

heightened moments of creation itself.

Writer

– Mulk Raj Anand

If you look at the map of the

world you will not find the village of Madhubani on it. Even if you can trace

the contours of the saried woman, which is the shape of Bharat Mata, you will

not find the beautiful mole on her face called Madhubani. But if you translate

the word Madhubani, you will soon know where it could be. The forest of honey,

which is the literal meaning of the name of the village, could be anywhere in

the vast landscape of our subcontinent.

If you look at the map of the

world you will not find the village of Madhubani on it. Even if you can trace

the contours of the saried woman, which is the shape of Bharat Mata, you will

not find the beautiful mole on her face called Madhubani. But if you translate

the word Madhubani, you will soon know where it could be. The forest of honey,

which is the literal meaning of the name of the village, could be anywhere in

the vast landscape of our subcontinent.  This urge for connection, for

absorption, and salvation, became the curve of the inner journey towards the

Self through the outward strayings in the mundane world.

This urge for connection, for

absorption, and salvation, became the curve of the inner journey towards the

Self through the outward strayings in the mundane world. The child, or the primitive,

creates an image in the likeness of what he or she wishes to become. Words are

vague. They only affect the soul where they are rhythmically intoned or

rhetorically delivered by an orator, or breathed in magical whispers by a

priest into the ear as Sruti, inspired by God. Images are more precise because

they are concrete. They picture vibrant feelings, metaphors and recreate myths,

so that we may remember the shape, size and texture of the spirit which has

hovered over the head, or is moving about in the soul, as a fleeting feeling.

When made and put on the mandala and holified by puja, the image as icon

affords the worshipper rest in the symbol, against the torment of not being

able to connect with a god or goddess through changing emotions. For instance,

once the imagination, recalling the memory of thunder and lightning, has

conceived the image of the God Indra driving his chariot across the sky, so

fast that the wheels create terrible sounds and spread sparks of fire, the

spirit of this dynamic god becomes incarnate on a wall when drawn as a concrete

expression.

The child, or the primitive,

creates an image in the likeness of what he or she wishes to become. Words are

vague. They only affect the soul where they are rhythmically intoned or

rhetorically delivered by an orator, or breathed in magical whispers by a

priest into the ear as Sruti, inspired by God. Images are more precise because

they are concrete. They picture vibrant feelings, metaphors and recreate myths,

so that we may remember the shape, size and texture of the spirit which has

hovered over the head, or is moving about in the soul, as a fleeting feeling.

When made and put on the mandala and holified by puja, the image as icon

affords the worshipper rest in the symbol, against the torment of not being

able to connect with a god or goddess through changing emotions. For instance,

once the imagination, recalling the memory of thunder and lightning, has

conceived the image of the God Indra driving his chariot across the sky, so

fast that the wheels create terrible sounds and spread sparks of fire, the

spirit of this dynamic god becomes incarnate on a wall when drawn as a concrete

expression.  The underlying idea of seeking

alliance with the image, is enacted as a drama in a festival like Durga Puja.

The images of the Goddess are made by the female folk or by the local

craftsmen. They are worshipped during the special festivals, at a particular

time of the year. The powers of the goddess are sought to be absorbed in one's

own inner life through worship. And then the image is thrown into the river, so

that it may become part of the cosmos, to be made again the next year, but

leaving the residue of the feeling of its force in the worshipper, so that he

or she can turn inwards and recall the image at will. The intention behind the

ritualistic use of the icon made the whole tradition of the art of India

possible. Every idol is for contemplation, in a dhyanamantra, or is meant to

evoke the vision of a concrete divinity, by seeking whose powers, in the

grooves of one's person, the awareness of the worshipper can extend itself

beyond the everyday round, and thus acquire ineffable devotion to the higher

self which may be exteriorised.

The underlying idea of seeking

alliance with the image, is enacted as a drama in a festival like Durga Puja.

The images of the Goddess are made by the female folk or by the local

craftsmen. They are worshipped during the special festivals, at a particular

time of the year. The powers of the goddess are sought to be absorbed in one's

own inner life through worship. And then the image is thrown into the river, so

that it may become part of the cosmos, to be made again the next year, but

leaving the residue of the feeling of its force in the worshipper, so that he

or she can turn inwards and recall the image at will. The intention behind the

ritualistic use of the icon made the whole tradition of the art of India

possible. Every idol is for contemplation, in a dhyanamantra, or is meant to

evoke the vision of a concrete divinity, by seeking whose powers, in the

grooves of one's person, the awareness of the worshipper can extend itself

beyond the everyday round, and thus acquire ineffable devotion to the higher

self which may be exteriorised.  We cannot, therefore, equate

the rasa, or flavour, which seeps into the devotee, with the aesthetic delight

which is the ideal of Western art, though rasa includes appreciation of forms.

But it denotes more comprehensive appreciation than the aesthetic term of Clive

Bell's 'significant form'.

We cannot, therefore, equate

the rasa, or flavour, which seeps into the devotee, with the aesthetic delight

which is the ideal of Western art, though rasa includes appreciation of forms.

But it denotes more comprehensive appreciation than the aesthetic term of Clive

Bell's 'significant form'.  The ritual painting is a simple

process. Certain symbols had been handed down by tradition. The recreation of

those in the alpana of the threshold or on the walls has been repeated day

after day without much variation. Perhaps on a festival, the grandmother of the

family, or the older aunt, may bring out, from the welter of images, a memory

image from her own youth in another village. The form of some flowers, or the

vessel in which the flowers are put, may thus become a variation on the old

theme.

The ritual painting is a simple

process. Certain symbols had been handed down by tradition. The recreation of

those in the alpana of the threshold or on the walls has been repeated day

after day without much variation. Perhaps on a festival, the grandmother of the

family, or the older aunt, may bring out, from the welter of images, a memory

image from her own youth in another village. The form of some flowers, or the

vessel in which the flowers are put, may thus become a variation on the old

theme. There are other creative

talents in Jitwanpur. In fact, almost every second person in a family paints.

There are other creative

talents in Jitwanpur. In fact, almost every second person in a family paints.  In the deeper layers of such

creativeness, is the intent to offer the sacrifice of one's self to the gods.

It is conceivable that though the ancient Aryan Yajnas or self sacrificial

ceremonies by burning clarified butter, so that the heat of the passion should

rise to the heavens and the earth be purified.

In the deeper layers of such

creativeness, is the intent to offer the sacrifice of one's self to the gods.

It is conceivable that though the ancient Aryan Yajnas or self sacrificial

ceremonies by burning clarified butter, so that the heat of the passion should

rise to the heavens and the earth be purified.  Actually, if we go to the

sources of creativeness in our civilisation, we find that the gods and

goddesses being our own higher incarnations and near neighbours, the invocation

of them is a purely human act, subject to no other law, except the vitality of

the rhythmic impulse which creates forms in different proportions, contours,

with emphasis on colours according to the individual talent of the painter.

Actually, if we go to the

sources of creativeness in our civilisation, we find that the gods and

goddesses being our own higher incarnations and near neighbours, the invocation

of them is a purely human act, subject to no other law, except the vitality of

the rhythmic impulse which creates forms in different proportions, contours,

with emphasis on colours according to the individual talent of the painter.  Unlike other folk of other

areas, the Madhubani painters, both Brahmins and Harijans, venture into the

realm of the gods, to dissolve their fears in the continuous resurgence of the

hope of receiving from the beneficent holies, for their body-souls, a certain

depth in which may be resolved the daily predicament of being-in-this-world

situation.

Unlike other folk of other

areas, the Madhubani painters, both Brahmins and Harijans, venture into the

realm of the gods, to dissolve their fears in the continuous resurgence of the

hope of receiving from the beneficent holies, for their body-souls, a certain

depth in which may be resolved the daily predicament of being-in-this-world

situation.  The folk in a village find that

they have to survive in the hamlet on their own mental and physical resources.

Some of the questions of the daily life have been answered in the recitals. All

the desires, emotions, frustrations, aspirations, lusts, greeds, jealousies,

have been expiated in the myths about the gods, who were originally based on

heroes or exalted fantasies of behavior, which were models of angels against

the evil demons. And behind the gods, there is lurking, always, the Supreme

God, the exalted, the unreachable, the impenetrable, who has inspired the

essence of the good, the beautiful and truthful in all creatures from which

they can hark back in yearnings and desire, which become myth, and which are

the means of reaching him in moments of ecstasy that is to say in being

oneself.

The folk in a village find that

they have to survive in the hamlet on their own mental and physical resources.

Some of the questions of the daily life have been answered in the recitals. All

the desires, emotions, frustrations, aspirations, lusts, greeds, jealousies,

have been expiated in the myths about the gods, who were originally based on

heroes or exalted fantasies of behavior, which were models of angels against

the evil demons. And behind the gods, there is lurking, always, the Supreme

God, the exalted, the unreachable, the impenetrable, who has inspired the

essence of the good, the beautiful and truthful in all creatures from which

they can hark back in yearnings and desire, which become myth, and which are

the means of reaching him in moments of ecstasy that is to say in being

oneself.

This blog wonderfully describes the beauty of madhubani paintings. Known for their intricate patterns and cultural significance, these artworks bring life to plain walls. If you’re planning to buy authentic and high-quality Madhubani paintings online, Vibecrafts is the best destination. Their collection blends tradition with style, making it ideal for modern homes.

This blog perfectly highlights the richness of MADHUBANI PAINTING, known for its detailed patterns and cultural depth. Such art instantly elevates interiors with heritage charm. If you’re planning to buy authentic and high-quality Madhubani paintings online, Vibecrafts is the best choice. Their collection blends traditional beauty with modern appeal at affordable prices

This blog perfectly highlights the beauty of madhubani painting, known for their intricate patterns and cultural richness. They don’t just decorate walls but also connect us to tradition. If you’re looking to buy authentic and premium-quality Madhubani paintings online, Vibecrafts is the ideal choice. Their collection combines heritage with modern appeal, making them perfect for stylish homes

This blog beautifully highlights the essence of Madhubani painting – intricate designs, cultural symbolism, and vibrant colors that transform walls into storytelling canvases. If you’re planning to buy authentic and premium-quality Madhubani paintings online, Vibecrafts is the best destination. Their collection perfectly blends heritage with modern aesthetics at affordable prices.