The art of painting has been a

medium of both expression and communication from the earliest known period of

history. Man, as nomad, wandering in search of food and security, gradually

discovered a language of line and form for expressing his ideas; which account

for pre-historic paintings appearing in rock shelters. At a later period, this

found expression in the paintings on chalcolithic pottery discovered at various

centres. In India, the patterns were either geometric or were styled after the

flora and fauna and at times depicted human figures.

The art of painting has been a

medium of both expression and communication from the earliest known period of

history. Man, as nomad, wandering in search of food and security, gradually

discovered a language of line and form for expressing his ideas; which account

for pre-historic paintings appearing in rock shelters. At a later period, this

found expression in the paintings on chalcolithic pottery discovered at various

centres. In India, the patterns were either geometric or were styled after the

flora and fauna and at times depicted human figures.

The art of painting in India

progressed gradually and it reached its zenith during the Satavahana period (2nd

- 1st B.C.) and also the Gupta-Vakataka period (5th-6th

A.D.). Mainly of the Buddhist theme, the paintings were on the large canvas of

granite walls of the Ajanta caves. The style was line-oriented and natural,

besides being brilliant in colour. The painters drew inspiration from the

legends related to the previous incarnations of Buddha.

The pattern of large scale wall

painting which had dominated the scene, witnessed the advent of miniature

paintings during the 11th & 12th centuries. This new

style figured first in the form of illustrations etched on palm-leaf

manuscripts. The contents of these manuscripts included literature on the

Buddhism and Jainism. In eastern India, the principle centres of artistic and

intellectual activities of the Buddhist religion were Nalanda, Odantapuri,

Vikramshila and Somarupa situated in the Pala kingdom (Bengal and Bihar).

Buddhist works like the Ashtasahasrika-Prajnaparamita, the Mahamayuri and the

Pancharaksha are few examples to cite, which were illustrated with Buddhist

deities in late Ajanta style. In western India, however, it was the Jain faith

which dominated, Rajasthan, Gujarat. and Malwa being the principle centres of

Jain religion and art. Apart from the Kalkacharya Katha and the Kalpasutra, two

well-known Jain treatises, Hindu themes such as the Balagopal Stuti as well as

secular works like the Vasanta Vilas found expression on palm-leaf

illustrations and came be known as the Jain or Western Indian Style of

painting.

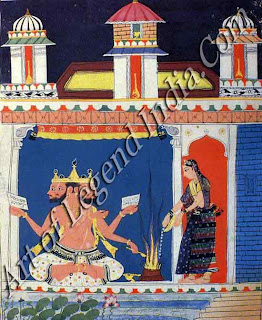

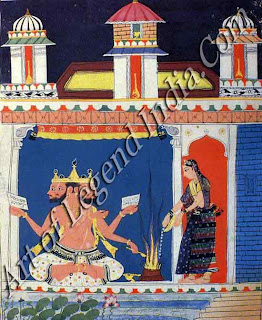

The Jain Style is unique as it

bears an exaggerated linear quality. Facial outlines are emphasized, the nose

is long and sharp, and the eyes are shaped like petals with the farther eye

projected beyond the outline of the face. The backgrounds are illuminated in

shades of dark blue, red and green or yellow. Gold is used for decorative

purpose, especially in the manuscripts of a later era, which were done on

paper, a medium, that had replaced the palm-leaf.

The Jain Style is unique as it

bears an exaggerated linear quality. Facial outlines are emphasized, the nose

is long and sharp, and the eyes are shaped like petals with the farther eye

projected beyond the outline of the face. The backgrounds are illuminated in

shades of dark blue, red and green or yellow. Gold is used for decorative

purpose, especially in the manuscripts of a later era, which were done on

paper, a medium, that had replaced the palm-leaf.

In these the compositional

format is confined to figures or objects generally arranged in horizontal

bands.

It was in the 14th century

A.D. that paper replaced the palm-leaf. The Jain Style of paintings attained a

high degree of development by the late 15th and early 16th century.

A new trend in manuscript illustration was set by a manuscript of the Nimatnama

painted at Mandu, during the reign of Nasir Shah (1500-1510 A.D.). This

represented a synthesis of the indigenous and the Persian Style, though it was

the latter which dominated the Mandu manuscripts. There was another style of

painting known as Lodi Khuladar that flourished in the Sultanate's dominion of

North India extending from Delhi to Jaunpur during the late 15th and early 16th

century. The best known example of the Lodi Style is the famous Aranyaka Parvan

belonging to the Asiatic Society, Bombay painted in 1516 A.D. during the

victorious reign of Sikandar Shah Lodi at Kachuvava, about 57 miles away from

Agra. Fine specimens of paintings in jaur Style can be seen in the well-known

manuscripts such as the Chaura Panchashika and the Gita-Govinda. This style is

marked by the ornaments adorning the women and their pendulous breasts, besides

the chequered designs of their garments. The figures have large eyes and

exaggerated profiles. Though emanating from the Jain Style of Delhi and

Jaunpur, this form has striking characteristics of its own.

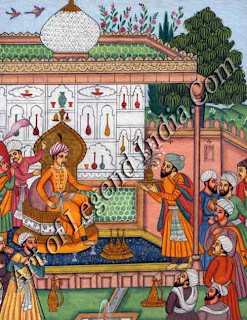

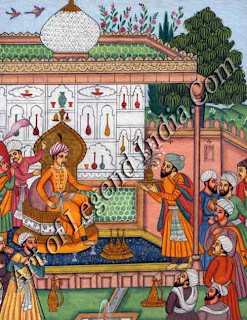

Akbar's reign (1556-1605)

ushered a new era in Indian miniature painting. He was the first monarch who established

in India an atelier under the supervision of two Persian master-artists, Mir

Sayyed Ali and Abdul-ul-Samad Khan. Earlier, both of them had served under the

patronage of Humayun in Kabul and accompanied him to India when he regained his

throne in 1555. Later, a number of artists were engaged to work under their

guidance to decorate Akbar's imperial studio at Fatehpur Sikri. One of the

first productions of that school of painting was the Hamzanama series, which,

according to the court historian, Badayuni, was started in 1567 and completed

in 1582. It is interesting to note that most of the artists belonged to the

Hindu communities hailing from Gujarat, Gwalior and Kashmir, who gave birth to

a new school of painting, popularly known as the Mughal School of Painting.

This synthesis of the Saffavid School and the indigenous kalams of miniature

art owe a debt to the secular outlook of Akbar. And it proved to be a landmark

in the history of Indian miniature painting. Akbar commissioned a large number

of manuscripts, illustrated in this style, for his Imperial Library. However,

this style of painting reached its zenith during the reigns of Jahangir

(1605-1627) and Shah Jahan (1628-1658), but declined rapidly during the years

that followed under the rule of Aurangzeb (1658-1707).

The earliest known manuscript

illustrated in this fashion during Akbar's regime is the

Duwal-Rani-Khizar-Ichani: Written by the celebrated poet Amir Khusro, the

illustrations are attributed to Mir Sayyed Ali, the master-painter, who

undertook the work in 1568. The paintings of the liamzanama which represented

the most ambitious project undertaken during the golden era of Akbar, were

executed on large canvas made of cotton cloth. Initially, the work was started

by about 30 artists, but their number grew to more than a hundred at the time

of its completion. The work on these illustrations served as an excellent

training ground for the painters of the royal atelier. The style of Mughal

paintings is distinguished by the dramatic action and bold brush work. Apart

from the Hamzanama, many other manuscripts such as the Razmanama, the

Baburnama, the Akbarnama etc., were also illustrated in similar vein.

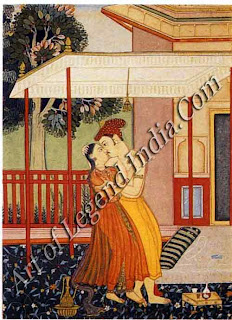

It was in the last quarter of

the 16th century that European influence began to affect the Mughal School.

Hence, a number of Christian themes were also painted by the Mughal artists.

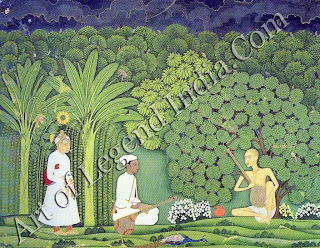

Jahangir was an enthusiastic patron of the arts. He possessed an innate quality

for the appreciation of painting and talent for observing the nature keenly. Whenever

he came across an unusual plant or bird or animal, he instructed his artists to

paint them. Particularly, Mansur, one of the most talented painters excelled in

animal and bird motifs. The art of painting attracted and charmed Jahangir so

much that his period is remarkable for beautiful illustrations of several

manuscripts. Jahangir's period is characterised by naturalism, both in colour

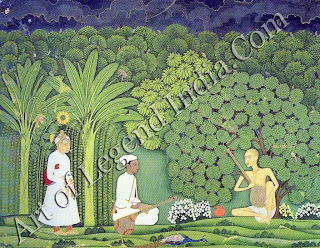

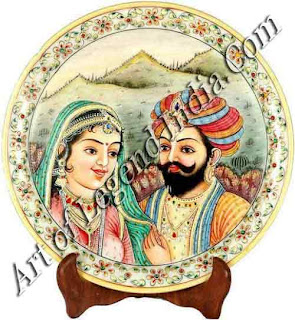

and form. During Shah Jahan's reign (1628-1658), the Mughal artists' favorite

themes for paintings were emperors and princes visiting Sufi saints. In

addition, court scenes, portraits and studies of birds and animals continued to

be depicted.

The fine quality of the Mughal

painting was sustained during the period of Shah Jahan, even though he paid

greater attention to architecture. The high quality work of the earlier reigns

did not survive during the period of Aurangzeb, although some good portraiture

and hunting scenes were executed in his time. Being an orthodox Muslim, he did

not encourage the art of painting. However, in the reigns of Farrukhsyiar

(1713-1719) and Muhammed Shah (1719-1748), the art of miniatnre painting was

revived again. A known romantic as Muhammad Shah was, love scenes and romantic

subjects began to feature frequently, which seemed to rebound on Aurangzeb's

puritanical attitude.

The era of Mughal painting came

to an end during the period of Shah A lam (1759-1806) when the Mughal empire

was virtually confined to an area enclosed by the walls of the Red Fort in

Delhi.

The era of Mughal painting came

to an end during the period of Shah A lam (1759-1806) when the Mughal empire

was virtually confined to an area enclosed by the walls of the Red Fort in

Delhi.

The style of paintings in the

provincial cities of the Mughal empire such as Murshidabad, Faizabad, Lucknow

and Patna has been described as Provincial Mughal. The Mughal Governors of

these provinces had assumed independent status following the decline of Mughal

empire during the middle of the 18th century. There were no drastic changes in

the Provincial Mughal Style of painting, but it has certain recognisable

features of its own. Mir Chand was one of the best known artists of this period.

Other provincial artists sought to imitate earlier work to suit the varying

tastes of their patrons rather than evolving distinctive styles of their own.

As for the Deccani painting,

initially it was a product of the Sheraz Style of Persian painting and the

local art forms of the Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar; Later, it was influenced

by the Mughal Style during the late 17th and 18th century. The earliest

surviving examples of Deccan; painting go back to circa A.D. 1565-1567 and are

now scattered in many collections belonging to A hmadnagar and Bijapur Schools.

A school of Deccani painting also flourished at Golconda, the style of which is

remarkably consistent in quality and is a combination of a high degree of

technical excellence with refinement of line and a subtle richness in its

colour palette.

The Bijapur School of painting

was patronized and developed under the powerful king Ali Adil Shah I(1558-1580)

and his successor, Ibrahim Adil Shah I (1580-1627), a great lover of art. An

illustrated manuscript of the Nujum-ul-ulum, a book on astronomy which was

painted at Bijapur during 1580, is the most notable work of the early Bijapur

School. Prior to this, the Tarif-i-Husain Shahi manuscript was written and

illustrated at A hmadnagar during 1565-1567. The Golconda School commenced

under Ibrahim in the middle of the 17th century and continued till the period

of A bdullah Qutub Shah (1626-1672) and last Golconda ruler Tana Shah

(1672-1687). The style of this school was distinguished by rich colours,

considerable use of gold and the frequent use of unusual architectural forms.

The art of painting in the Deccan continued till late 18th century but it

became increasingly decorative. However, there are some fine sets of the

Ragamala, which were painted during 1725-1778.

The Bijapur School of painting

was patronized and developed under the powerful king Ali Adil Shah I(1558-1580)

and his successor, Ibrahim Adil Shah I (1580-1627), a great lover of art. An

illustrated manuscript of the Nujum-ul-ulum, a book on astronomy which was

painted at Bijapur during 1580, is the most notable work of the early Bijapur

School. Prior to this, the Tarif-i-Husain Shahi manuscript was written and

illustrated at A hmadnagar during 1565-1567. The Golconda School commenced

under Ibrahim in the middle of the 17th century and continued till the period

of A bdullah Qutub Shah (1626-1672) and last Golconda ruler Tana Shah

(1672-1687). The style of this school was distinguished by rich colours,

considerable use of gold and the frequent use of unusual architectural forms.

The art of painting in the Deccan continued till late 18th century but it

became increasingly decorative. However, there are some fine sets of the

Ragamala, which were painted during 1725-1778.

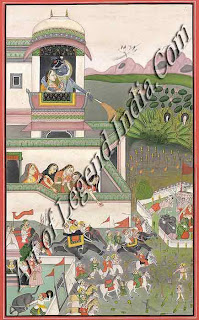

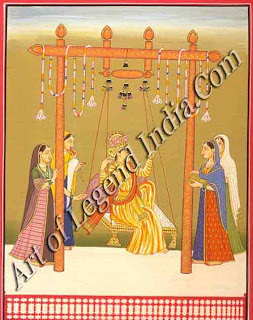

Rajasthani paintings covered a

wide area including Malwa, Bundelkhand, Mewar, Bundi, Kota, Jaipur, Bikaner, Si

rohi, Sawar, Kishangarh and Marwar. What is interesting to note is that each

centre developed its own individual characteristics. In Rajputana, painting was

already in vogue in the form of Western Indian or Jain Style. This had provided

a base for the growth of various schools of painting under the influence of

popular Mughal School from circa 1590-1600. Nevertheless, the Rajasthani

kalanis developed their own styles in the years that followed.

The earliest available set of

Rajasthani painting is the Ragamala done by a Muslim artist, Nissardin, in 1605

at Chawand in Mewar. Yet another Ragamala in the Mewar Style was painted by the

artist Sahibdin in 1628. Sahibdin's work greatly influenced the development of

early Rajasthani painting in Mewar. He became the principle artist of the Mewar

court during the reign of jagat Singh I (1628-1652).

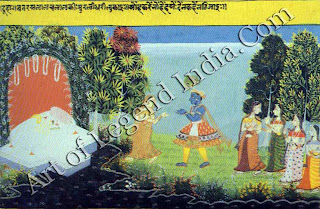

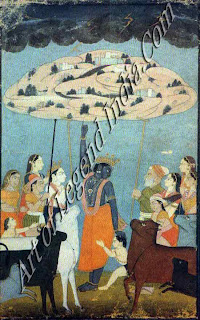

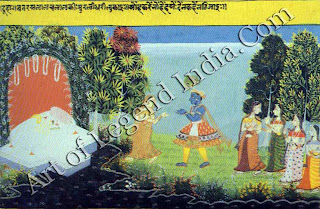

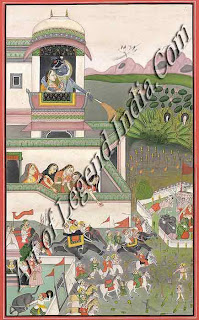

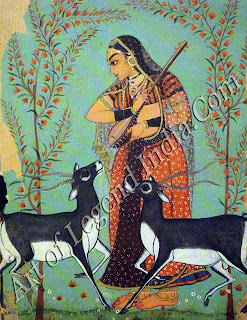

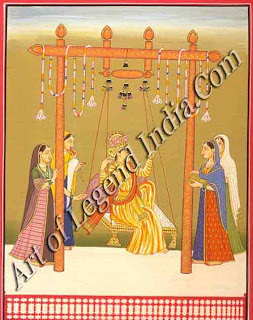

The rise of Vaisnavism and the

Bhakti cult in Rajasthan exercised a marked influence both on literature and

pictorial art. Krishna became the 'supreme god, while Radha was considered as

the symbol of divine love.

The rise of Vaisnavism and the

Bhakti cult in Rajasthan exercised a marked influence both on literature and

pictorial art. Krishna became the 'supreme god, while Radha was considered as

the symbol of divine love.

Most of the themes in art and

literature revolved largely around them. The famous literary and poetic works

such as the Gita-Govinda written by the court poet Jay Deva who lived in Bengal

in the 12th century; the Rasikapriya by Kesava Das of Orcha (1555-1617); the

Amaru Shataka, the hundred love lyrics by Amaru; Bihari's Satsai (circa

1603-1663), the classification of its heroes and heroines theme, better known

as the Nayika Bheda, were repeatedly illustrated with these forms. Apart from

mythological stories, the Devi Purana, the Bhagavata Purana, the Ramayana, the

Mahabharata, the Ragamala, the Baramasa and the activities of daily life were

extensively painted.

One striking feature of

Rajasthani painting is the arrangement of figures as even small figures are not

obscured in the composition. The background, the flora and fauna and the

symbols help the composition to express an intensity of feelings and emotions.

Architecture usually painted in the background, is used as a device to create

perspective and depth. Faces are often modelled with a tinge of colour to

impart a certain roundness to them. In the 18th century, the names of rulers,

artists and even dates and titles sometimes appear on the upper margin of the

paintings. Foremost amongst the Rajasthani schools are those of Mewar, Malwa,

Jaipur, Jodhpur, Nagaur, Sirohi, Kota, Bunch, Bikaner and Kishangarh, while

many thikanas (feudal baronies) such as Deogarh, Ghanerao, Malpura, Pali etc.

also had painters at their own courts.

The Malwa Style is marked by

bold and strong colours. Figures with long wide eyes are usually projected

against monochrome backgrounds of varying rich tonalities. The composition are

very simple and the picture space is often divided into compartments in order

to separate one scene from the other. An important series of paintings in the

Malwa Style is a Rasikapriya dated 1634, which was certainly painted in Orcha.

There are also illustrations in the Ramayana and the Bhagavata Purana and there

are good reasons to believe that they were painted about 1642-1645 for the

queen, Hira Rani, wife of Pahar Singh of Orcha. An Amaru Shataka series was

painted in circa 1652 at Nasaratgarh near Mandu, while a Ragamala series (now

in the National Museum) was painted at Narsinghagarh by an artist named Madhav

Das.

Paintings from Mewar assume a

great variety for the use of a wide range of colours such as saffron, yellow,

ochre, navy blue, brown, crimson, etc. The backgrounds usually have stylised

architecture consisting of domed pavilions and small turrets. The treatment of

trees is only partially naturalistic, and the foregrounds are decorated with

flowers and birds. The menfolk sport a janza, a long garment which is both

plain and fuliskirted. A scarf is worn over one shoulder and sometimes around

the waist as well. The turban is either loosely wound or has a band tied

tightly around it.

Marwar was an important centre

of Gujarati-Jain art activities. It was at Marwar and other places such as

Jodhpur, Pali and Nagaur that a variety of sub-schools of painting developed

during 17th-19th centuries. Of these, Jodhpur is the most important centre of

the Marwar School of painting. The turban seen in Marwar painting has its own

characteristics. It is funnel-shaped and markedly high. The faces are usually

drawn in profile, and bright colours are preferred in the composition. Spiral

clouds are also shown streaming on the horizon. A large number of portraits,

court scenes and themes such as Baramasa are to be found in the Jodhpur Style.

Though paintings at Pali, a thikana, belonging to the Marwar School are

somewhat traditional, yet they are important to the art historians for there is

a dated Ragamala series of 1623 painted by an artist Viraji, several folios of

which are now in the National Museum. In Nagaur, another centre of the Marwar

School, we find among other subjects several important portraits executed in a

markedly dignified style.

Marwar was an important centre

of Gujarati-Jain art activities. It was at Marwar and other places such as

Jodhpur, Pali and Nagaur that a variety of sub-schools of painting developed

during 17th-19th centuries. Of these, Jodhpur is the most important centre of

the Marwar School of painting. The turban seen in Marwar painting has its own

characteristics. It is funnel-shaped and markedly high. The faces are usually

drawn in profile, and bright colours are preferred in the composition. Spiral

clouds are also shown streaming on the horizon. A large number of portraits,

court scenes and themes such as Baramasa are to be found in the Jodhpur Style.

Though paintings at Pali, a thikana, belonging to the Marwar School are

somewhat traditional, yet they are important to the art historians for there is

a dated Ragamala series of 1623 painted by an artist Viraji, several folios of

which are now in the National Museum. In Nagaur, another centre of the Marwar

School, we find among other subjects several important portraits executed in a

markedly dignified style.

Bikaner was one of the most

important states of Rajasthan. This state was established in the 15th century

by a chieftain named Bika. It was during the-middle of the 17th century that a

few artists from the Mughal School visited Bikaner and worked there under its

patronage. Ali Raza, an Ustad (master-painter) from Delhi was amongst them. The

names of some other well-known Bikaner artists are Ruknucidin and his son

Sahibdin, Isa, Mohammed Ibrahim and 'Alpha. Most of the Bikaner artists were

Muslim, and they worked in a style which although markedly Mughal in character,

had certain distinctive features of its own. The Bikaner Style is known for its

very fine draughtsmanship and subdued colour tonalities.

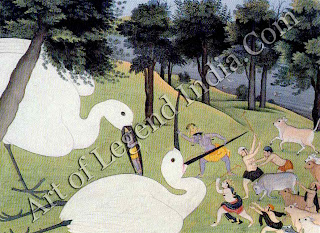

The Buildi School came into

existence during the early 17th century; an early influence was the popular

Mughal Style of a Ragamala series painted at Chunar near Banaras in 1591. An

example of the early Chunar series, Bhairon Ragini, is housed in the Allahabad

Museum and there are examples in other collections also. Originally mistaken as

a Bundi series, it is in fact a popular Mughal series which influenced the

early Bundi School for the Chunar series had come into the possession of a

family of Bundi-Kota artists sometimes about 1625-1630 and was used as a model

for painting scroll in Bundi and its sister state Kota. It was the influence of

the Chunar series that brought into existence the Bundi School. The Bundi

School was also influenced by the Deccan i painting to some extent. The Bundi artists

had their own standard in depicting feminine beauty: women are portrayted with

small round faces, receding foreheads, prominent noses and full cheeks, while

the female dress usually consists of a pyjama over which a transparent Jama is

worn. Another feature of the Bundi School is lush landscapes painted in vibrant

colours and massed with a variety of forms of trees and floral creepers, water

ponds with lotus flowers in the foreground, fish and birds. Sometimes a yellow

band appears on top of the painting with a text in Nagiri characters. Kota

state in the southern Rajasthan was separated from its sister state of Bundi in

1624.

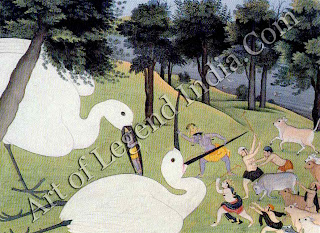

The Kota School is so close to

the Bundi School that at times it is difficult to assert whether a painting is

of the Bundi or the Kota kalam. Though a distinctive Kota Style evolved in

mid-17th century, similarities between Bundi and Kota painting continued in

many respects with discernible variations in details, costumes and methods of

shading the faces. The Kota hunting scenes, depicting princes and nobles with

their retinue engaged in hunting lions

and tigers in the rocky and somewhat sparsely wooded forests of that region,

are now world famous.

It was at Amber, the former

capital city of Rajasthan that the Jaipur School of painting originated. The

capital was shifted to the newly planned city of Jaipur only in 1728. The

rulers at Amber had maintained cordial relations with the Mughal emperors, and

this association left its impact on the artistic activities at Amber. Jaipur

paintings are plentiful and embrace a variety of subjects, but they neither

possess the subtler qualities as evidenced in the Bundi, Kota, Kishangarh or

Bikaner Schools nor bear the bolder qualities of Mewar and Marwar Schools of

Rajasthani painting.

It was at Amber, the former

capital city of Rajasthan that the Jaipur School of painting originated. The

capital was shifted to the newly planned city of Jaipur only in 1728. The

rulers at Amber had maintained cordial relations with the Mughal emperors, and

this association left its impact on the artistic activities at Amber. Jaipur

paintings are plentiful and embrace a variety of subjects, but they neither

possess the subtler qualities as evidenced in the Bundi, Kota, Kishangarh or

Bikaner Schools nor bear the bolder qualities of Mewar and Marwar Schools of

Rajasthani painting.

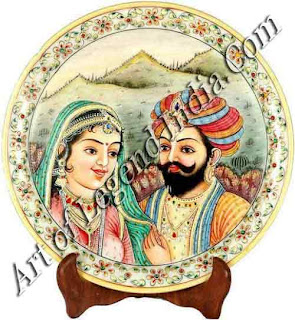

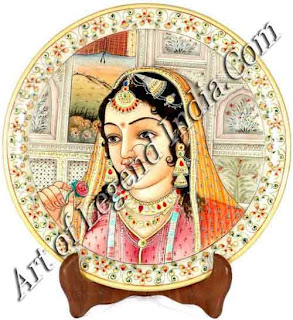

The state of Kishangarh was

founded by Kishan Singh, a younger brother of Raja Sur Singh of Jodhpur in

circa 1609. It was during the second quarter of the 18th century (1735-1748)

that some of the most charming pieces of Kishangarh painting were produced. Raja

Sawant Singh was on the throne during that period. A great patron of art and

literature as he was, he composed devotional songs in praise of Radha and

Krishna using the pseudonym of Nagari Das.

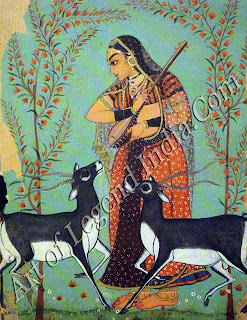

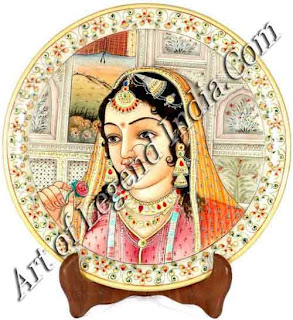

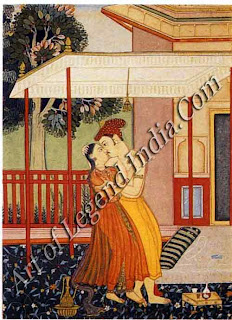

Kishangarh painting, at its

finest, is distinguished by its exquisite quality not to be found in other

Rajasthani schools and a distinctive type of female face with receding

forehead, arched eyebrows, lotus shaped eyes slightly tinged with pink, sharp

pointed nose, thin and sensitive lips and pointed chin. Nihal Chand was the

most important artist of Kishangarh, who is said to have worked there between

1735 - 1757 and probably even later. He executed beautiful portraits of Krishna

and Radha, the facial type for Radha being based on the exquisite countenance

of Sawant Singh's beloved mistress popularly known as Bani Thani. Krishna's

face in these paintings was also stylised to look somewhat similar, though as a

male countenance to the stylised face of Bani Thani. A statement made by some

writers that the stylised Kishangarh Radha was not based on the face of Bani

Thani is due to their ignorance of a tradition believed over two centuries by

well-known scholars of Hindi Brij Bhasa. In fact, there is a contemporary

painting of her approaching Sawant Singh who is performing Puja, and it is also

evident that the stylised Kishangarh Radha is based on the tall beautiful

figure and face of Bani Thani as seen in this painting. Those who opine that

these paintings are of a later date appear to be rather ignorant of the stylistic

features of Kishangarh paintings.

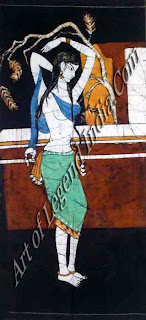

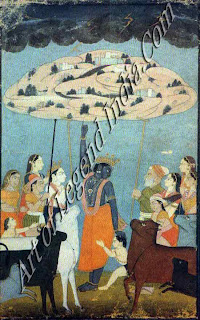

The art of miniature painting

in the Punjab hills known as Pahari painting was influenced to some extent by

the Mughal painting of Aurangzeb's period as well as paintings from Nepal,

probably via Kashmir, particularly in its stylised tree forms. Pahari paintings

had its beginning under Raja Kripal Pal of Basohli (1678-1731), a literary

minded ruler who was also a great devotee of Vishnu.

This school has many styles and

sub-styles as these paintings developed at various centres such as Basohli.

Guler. Chamba, 'Tehri, Garhwal, Nurpur, Mankot, Mandi, Kulu, Bilaspur etc.

under the patronage of their respective rulers.

This school has many styles and

sub-styles as these paintings developed at various centres such as Basohli.

Guler. Chamba, 'Tehri, Garhwal, Nurpur, Mankot, Mandi, Kulu, Bilaspur etc.

under the patronage of their respective rulers.

Krishna legend was a very

popular subject with the Pahari painters. Episodes from Krishna's life were illustrated

against the background of beautiful Pahari landscapes. Besides themes taken

from mythological legends and epics like the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the

Bhagavao Purana, the Krishna Lila and the Gita-Govinda, some very interesting

paintings of Devi were also painted. Nayaka-Nayika themes, portraits, huntings

scenes, toilet scenes and festivals such as Holi, love stories namely Madhu

Malti and Nala - Damyanti were also frequently illustrated.

Both male and female costumes

in Pahari paintings were influenced by the fashions adopted at the Mughat court

from time to time. Nevertheless, there

were also distinctive Pahari costumes, particularly those worn by females and

they are quite visible in these paintings.

The Basohli School is the

oldest one amongst Pahari Schools in the hill area. There is no evidence of any

Pahari painting earlier than the reign of Kirpal Pal. The work of some

itinerant artist of Mughal School visiting the hill states to execute

commissions should not be confused with Pahari paintings. The distinctive style

of Basohli with its primitive vitality emerged in the last quarter of the 18th

century under Raja Kripal Pal. It is characterised by vivid and bold colours.

Faces in the early Basohli paintings are oval in shape with receding foreheads

and large expressive eyes like lotus petals.

The landscape is stylised and

trees are often depicted in circular form. The composition is simple but

unique. Sometimes, a section and figures of the architecture are placed

separately into a square frame indicating a true understanding of space sense.

The Basohli Style spread over the neighbouring states remained in vogue till

the middle of the 18th century. A popular theme in Basohli painting

particularly during the reign of Kripal Pal was the Rasamanjari written by the

poet Bhanu Datta, a Maithili Brahmin, who lived in the 16th century in an area

called Tirhut in Bihar. A Basohli Rasamanjari series dated 1695 is a landmark.

It was illustrated by Devidas, a local painter of Basholi belonging to the Tarkhan

commu: nity, which produced many skilled aritsans. Amongst other styles of

Pahari painting, those of Guler and Kangra, are marked by far more naturalistic

treatment of figures and landscapes than seen in Basohli paintings. The figures

which are well-modelled and naturalistic are painted in soft and harmonious

colours. Whereas paintings of Garhwal school, developed from the Kangra style,

show an extensive use of leafless trees, the Kulu Style has folk elements with

squarish and somewhat ungainly figures.

The landscape is stylised and

trees are often depicted in circular form. The composition is simple but

unique. Sometimes, a section and figures of the architecture are placed

separately into a square frame indicating a true understanding of space sense.

The Basohli Style spread over the neighbouring states remained in vogue till

the middle of the 18th century. A popular theme in Basohli painting

particularly during the reign of Kripal Pal was the Rasamanjari written by the

poet Bhanu Datta, a Maithili Brahmin, who lived in the 16th century in an area

called Tirhut in Bihar. A Basohli Rasamanjari series dated 1695 is a landmark.

It was illustrated by Devidas, a local painter of Basholi belonging to the Tarkhan

commu: nity, which produced many skilled aritsans. Amongst other styles of

Pahari painting, those of Guler and Kangra, are marked by far more naturalistic

treatment of figures and landscapes than seen in Basohli paintings. The figures

which are well-modelled and naturalistic are painted in soft and harmonious

colours. Whereas paintings of Garhwal school, developed from the Kangra style,

show an extensive use of leafless trees, the Kulu Style has folk elements with

squarish and somewhat ungainly figures.

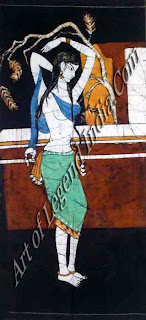

The Nurpur paintings are

characterised by tall women who have long limbs particularly below the waist

and are always elegantly attired. The Chamba Style is similar to that of Guler

paintings as several artists of this school came from Guler. In Mandi School,

we again find some folk elements particularly in the work done during the reign

of Raja Shamsher Singh. While Bilaspur also had a style of its own, which

extended to Sirmur, the work at Jammu was dominated by the masterly and

expressive draughtsmanship of the Nainsukh whose patron was Raja Balwant Singh

of Jammu, who is portrayed extensively in.Nainsukh paintings in all walks of

life. Nainsukh was the master-artist of Jammu school just as his elder brother

Manak was of Guier school. Both were sons of Pandit Sen of Guler. The family of

Pandit Sen is known for a number of noted artists who worked in various Pahari

states developing their own styles. After the death of Goverdhan Chand of Guler

in 1773, Manak, his two sons Kaushala and Paltu and his nephew Godhu worked at

the court of his successor Prakash Chand till circa A.D. 1785. Prakash Chand, a

great lover of arts had spent so lavishly by that time that he became a

bankrupt. Thereafter, Manak with his sons and nephew joined the court of Raja

Sansar Chand, paramount ruler of the hills, and painted there five sets of

paintings during 1785 and 1795. They are: the famous Bhagavat Purana, a

beautiful Ramayana series, a Satsai series painted as we know by Paitu, a

Ragamala now in the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi and a Baramasa

in. the possession of the descendants of Sansar Chand (Lambagaon family). The

style of these sets as the work of Manak, his sons and nephew is remarkable and

these sets are amongst the greatest achievements of Pahari paintings.

The processes and techniques

followed by the artists were almost uniform, simple and indigenous. Handmade

paper was mainly used as the base of the paintings. Thin sheets of paper, were

joined together to get the requisite thickness, on which the outline was drawn

in the light reddish brown or grey-black colour. A thin transparent white

coating was applied to the paper. Thereafter, a final drawing was made over the

white coating and then the colours were filled in. The pigments were obtained

from minerals and vegetables which were suspended in water with gum, for the

latter acted as a binding medium. Squirrel and camel hair were used in brushes.

Quite often, the painting was burnished, with glass or agate or stone from the

river Beas called 'Golla' to obtain the quality of brightness.

Writer

– Pramod Ganpatye

The art of painting has been a

medium of both expression and communication from the earliest known period of

history. Man, as nomad, wandering in search of food and security, gradually

discovered a language of line and form for expressing his ideas; which account

for pre-historic paintings appearing in rock shelters. At a later period, this

found expression in the paintings on chalcolithic pottery discovered at various

centres. In India, the patterns were either geometric or were styled after the

flora and fauna and at times depicted human figures.

The art of painting has been a

medium of both expression and communication from the earliest known period of

history. Man, as nomad, wandering in search of food and security, gradually

discovered a language of line and form for expressing his ideas; which account

for pre-historic paintings appearing in rock shelters. At a later period, this

found expression in the paintings on chalcolithic pottery discovered at various

centres. In India, the patterns were either geometric or were styled after the

flora and fauna and at times depicted human figures.  The Jain Style is unique as it

bears an exaggerated linear quality. Facial outlines are emphasized, the nose

is long and sharp, and the eyes are shaped like petals with the farther eye

projected beyond the outline of the face. The backgrounds are illuminated in

shades of dark blue, red and green or yellow. Gold is used for decorative

purpose, especially in the manuscripts of a later era, which were done on

paper, a medium, that had replaced the palm-leaf.

The Jain Style is unique as it

bears an exaggerated linear quality. Facial outlines are emphasized, the nose

is long and sharp, and the eyes are shaped like petals with the farther eye

projected beyond the outline of the face. The backgrounds are illuminated in

shades of dark blue, red and green or yellow. Gold is used for decorative

purpose, especially in the manuscripts of a later era, which were done on

paper, a medium, that had replaced the palm-leaf. The era of Mughal painting came

to an end during the period of Shah A lam (1759-1806) when the Mughal empire

was virtually confined to an area enclosed by the walls of the Red Fort in

Delhi.

The era of Mughal painting came

to an end during the period of Shah A lam (1759-1806) when the Mughal empire

was virtually confined to an area enclosed by the walls of the Red Fort in

Delhi.  The Bijapur School of painting

was patronized and developed under the powerful king Ali Adil Shah I(1558-1580)

and his successor, Ibrahim Adil Shah I (1580-1627), a great lover of art. An

illustrated manuscript of the Nujum-ul-ulum, a book on astronomy which was

painted at Bijapur during 1580, is the most notable work of the early Bijapur

School. Prior to this, the Tarif-i-Husain Shahi manuscript was written and

illustrated at A hmadnagar during 1565-1567. The Golconda School commenced

under Ibrahim in the middle of the 17th century and continued till the period

of A bdullah Qutub Shah (1626-1672) and last Golconda ruler Tana Shah

(1672-1687). The style of this school was distinguished by rich colours,

considerable use of gold and the frequent use of unusual architectural forms.

The art of painting in the Deccan continued till late 18th century but it

became increasingly decorative. However, there are some fine sets of the

Ragamala, which were painted during 1725-1778.

The Bijapur School of painting

was patronized and developed under the powerful king Ali Adil Shah I(1558-1580)

and his successor, Ibrahim Adil Shah I (1580-1627), a great lover of art. An

illustrated manuscript of the Nujum-ul-ulum, a book on astronomy which was

painted at Bijapur during 1580, is the most notable work of the early Bijapur

School. Prior to this, the Tarif-i-Husain Shahi manuscript was written and

illustrated at A hmadnagar during 1565-1567. The Golconda School commenced

under Ibrahim in the middle of the 17th century and continued till the period

of A bdullah Qutub Shah (1626-1672) and last Golconda ruler Tana Shah

(1672-1687). The style of this school was distinguished by rich colours,

considerable use of gold and the frequent use of unusual architectural forms.

The art of painting in the Deccan continued till late 18th century but it

became increasingly decorative. However, there are some fine sets of the

Ragamala, which were painted during 1725-1778.  The rise of Vaisnavism and the

Bhakti cult in Rajasthan exercised a marked influence both on literature and

pictorial art. Krishna became the 'supreme god, while Radha was considered as

the symbol of divine love.

The rise of Vaisnavism and the

Bhakti cult in Rajasthan exercised a marked influence both on literature and

pictorial art. Krishna became the 'supreme god, while Radha was considered as

the symbol of divine love.  Marwar was an important centre

of Gujarati-Jain art activities. It was at Marwar and other places such as

Jodhpur, Pali and Nagaur that a variety of sub-schools of painting developed

during 17th-19th centuries. Of these, Jodhpur is the most important centre of

the Marwar School of painting. The turban seen in Marwar painting has its own

characteristics. It is funnel-shaped and markedly high. The faces are usually

drawn in profile, and bright colours are preferred in the composition. Spiral

clouds are also shown streaming on the horizon. A large number of portraits,

court scenes and themes such as Baramasa are to be found in the Jodhpur Style.

Though paintings at Pali, a thikana, belonging to the Marwar School are

somewhat traditional, yet they are important to the art historians for there is

a dated Ragamala series of 1623 painted by an artist Viraji, several folios of

which are now in the National Museum. In Nagaur, another centre of the Marwar

School, we find among other subjects several important portraits executed in a

markedly dignified style.

Marwar was an important centre

of Gujarati-Jain art activities. It was at Marwar and other places such as

Jodhpur, Pali and Nagaur that a variety of sub-schools of painting developed

during 17th-19th centuries. Of these, Jodhpur is the most important centre of

the Marwar School of painting. The turban seen in Marwar painting has its own

characteristics. It is funnel-shaped and markedly high. The faces are usually

drawn in profile, and bright colours are preferred in the composition. Spiral

clouds are also shown streaming on the horizon. A large number of portraits,

court scenes and themes such as Baramasa are to be found in the Jodhpur Style.

Though paintings at Pali, a thikana, belonging to the Marwar School are

somewhat traditional, yet they are important to the art historians for there is

a dated Ragamala series of 1623 painted by an artist Viraji, several folios of

which are now in the National Museum. In Nagaur, another centre of the Marwar

School, we find among other subjects several important portraits executed in a

markedly dignified style.  It was at Amber, the former

capital city of Rajasthan that the Jaipur School of painting originated. The

capital was shifted to the newly planned city of Jaipur only in 1728. The

rulers at Amber had maintained cordial relations with the Mughal emperors, and

this association left its impact on the artistic activities at Amber. Jaipur

paintings are plentiful and embrace a variety of subjects, but they neither

possess the subtler qualities as evidenced in the Bundi, Kota, Kishangarh or

Bikaner Schools nor bear the bolder qualities of Mewar and Marwar Schools of

Rajasthani painting.

It was at Amber, the former

capital city of Rajasthan that the Jaipur School of painting originated. The

capital was shifted to the newly planned city of Jaipur only in 1728. The

rulers at Amber had maintained cordial relations with the Mughal emperors, and

this association left its impact on the artistic activities at Amber. Jaipur

paintings are plentiful and embrace a variety of subjects, but they neither

possess the subtler qualities as evidenced in the Bundi, Kota, Kishangarh or

Bikaner Schools nor bear the bolder qualities of Mewar and Marwar Schools of

Rajasthani painting.  This school has many styles and

sub-styles as these paintings developed at various centres such as Basohli.

Guler. Chamba, 'Tehri, Garhwal, Nurpur, Mankot, Mandi, Kulu, Bilaspur etc.

under the patronage of their respective rulers.

This school has many styles and

sub-styles as these paintings developed at various centres such as Basohli.

Guler. Chamba, 'Tehri, Garhwal, Nurpur, Mankot, Mandi, Kulu, Bilaspur etc.

under the patronage of their respective rulers.  The landscape is stylised and

trees are often depicted in circular form. The composition is simple but

unique. Sometimes, a section and figures of the architecture are placed

separately into a square frame indicating a true understanding of space sense.

The Basohli Style spread over the neighbouring states remained in vogue till

the middle of the 18th century. A popular theme in Basohli painting

particularly during the reign of Kripal Pal was the Rasamanjari written by the

poet Bhanu Datta, a Maithili Brahmin, who lived in the 16th century in an area

called Tirhut in Bihar. A Basohli Rasamanjari series dated 1695 is a landmark.

It was illustrated by Devidas, a local painter of Basholi belonging to the Tarkhan

commu: nity, which produced many skilled aritsans. Amongst other styles of

Pahari painting, those of Guler and Kangra, are marked by far more naturalistic

treatment of figures and landscapes than seen in Basohli paintings. The figures

which are well-modelled and naturalistic are painted in soft and harmonious

colours. Whereas paintings of Garhwal school, developed from the Kangra style,

show an extensive use of leafless trees, the Kulu Style has folk elements with

squarish and somewhat ungainly figures.

The landscape is stylised and

trees are often depicted in circular form. The composition is simple but

unique. Sometimes, a section and figures of the architecture are placed

separately into a square frame indicating a true understanding of space sense.

The Basohli Style spread over the neighbouring states remained in vogue till

the middle of the 18th century. A popular theme in Basohli painting

particularly during the reign of Kripal Pal was the Rasamanjari written by the

poet Bhanu Datta, a Maithili Brahmin, who lived in the 16th century in an area

called Tirhut in Bihar. A Basohli Rasamanjari series dated 1695 is a landmark.

It was illustrated by Devidas, a local painter of Basholi belonging to the Tarkhan

commu: nity, which produced many skilled aritsans. Amongst other styles of

Pahari painting, those of Guler and Kangra, are marked by far more naturalistic

treatment of figures and landscapes than seen in Basohli paintings. The figures

which are well-modelled and naturalistic are painted in soft and harmonious

colours. Whereas paintings of Garhwal school, developed from the Kangra style,

show an extensive use of leafless trees, the Kulu Style has folk elements with

squarish and somewhat ungainly figures.

0 Response to "A Guide to The Indian Miniature Painting"

Post a Comment