A

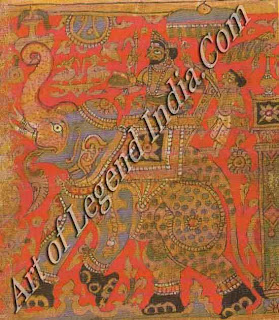

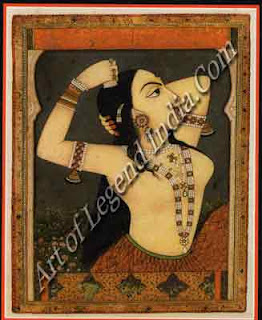

remarkable flowering of regional schools of painting took place at the Muslim

and Hindu courts of northern India and the Deccan between the 16th and

19th centuries. Today this enormous production of pictures and illustrated

manuscripts has been largely dispersed by the disinherited princely families

and is found in public and private collections throughout the world. Even to

modern man, living in Babel of visual information, the appeal of Indian

pictures is immediate. They were made above all to delight the eye by their

rich colour harmonies and fluent clarity of line and, by keeping in each case

to a traditional range of expressive conventions, to impart mainly auspicious

or pleasurable sentiments, whether of royal grandeur, devotional wonder or a

refined eroticism. It was an art inseparable from the courtly milieu and its

preoccupations both with religious, literary and musical culture and with the

self-regarding imagery of power and display.

A

remarkable flowering of regional schools of painting took place at the Muslim

and Hindu courts of northern India and the Deccan between the 16th and

19th centuries. Today this enormous production of pictures and illustrated

manuscripts has been largely dispersed by the disinherited princely families

and is found in public and private collections throughout the world. Even to

modern man, living in Babel of visual information, the appeal of Indian

pictures is immediate. They were made above all to delight the eye by their

rich colour harmonies and fluent clarity of line and, by keeping in each case

to a traditional range of expressive conventions, to impart mainly auspicious

or pleasurable sentiments, whether of royal grandeur, devotional wonder or a

refined eroticism. It was an art inseparable from the courtly milieu and its

preoccupations both with religious, literary and musical culture and with the

self-regarding imagery of power and display.

Except

at the Mughal court, where the best of them were un-usually honoured, the

painters themselves were generally artisans of no special status, hereditary

craftsmen who transmitted a continuous tradition which was modified in each

generation as a result of their patron's interest or lack of it in their work.

Stylistic changes can often be related to the personalities of individual

rulers, so far as we know them: they are on the whole better recorded by the

more historically minded Muslim chroniclers than by the Hindu bards and

genealogists.

The

medium used by the artists was gouache: mineral, vegetable and animal pigments

mixed with gum arabic, often with embellishment in gold and silver, applied to a

prepared paper or, more rarely, cloth support. At the Muslim courts the finished

work was often mounted within wide paper borders which were ruled and decorated

in gold and colour; Rajput pictures tend to have an integral painted border,

often a bright lacquer red. The whole picture seldom exceeded a size suitable

for holding in the hand. Although Indian paintings are nowadays seen hung

uncompromisingly in rows in galleries, they were not intended for wall display.

In the palaces their designs were sometimes enlarged and coarsened in mural

paintings, of which few early examples survive. Paintings on paper were kept

bound in albums or stacked in cloth-wrapped bundles in libraries or

store-rooms, from which they would be fetched by command, to be appreciatively

inspected at intimate gatherings of nobles or ladies.

An

audience of this kind would have understood naturally the pictorial conventions

employed by artists of their own and neighboring courts, and the densely

interwoven mythological, poetical and musical allusion implicit in their

subject matter. Such resonances could be lost on the modern viewer, who may

also be bewildered by the sheer diversity of the regional court styles

represented in museum collections, with subjects ranging from naturalistic

portraits of rulers and courtiers to farouche depictions of Hindu deities or of

the modes of North Indian music (ragas) personified as gods, princes and

ladies. This diversity reflects above all the differing religious and cultural

traditions of the four principal dynastic and regional centres of patronage.

From

the late r6th century the most influential of these was the prolific atelier of

the Muslim Mughal emperors, who dominated northern India from their courts at

Agra, Delhi and Lahore. It was complemented by the distinct traditions

maintained by the independent Muslim sultanates of the Deccan until their

annexation by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the 168os. At the same time, a

great variety of local styles, influenced by Mughal example but fundamentally

indebted to older, indigenous traditions, flourished at the semi-independent

Hindu courts of the Rajputs. These formed two geographically separate groups,

in Rajasthan and Central India to the south and in the Punjab Hills to the

north. If the Rajasthani and Pahari (or 'Hill) schools did not often achieve or

seek the technical refinement of the best Mughal and Deccani painting, they

made up for it both in intensity of feeling and in their greater longevity.

Their relative isolation and closeness to folk roots enabled them to survive

the political disasters of the T 8th century and, in the case of some

Rajasthani schools, to continue into the mid- 9th century, or even later at a

few courts, where the undermining influences of Western art and photography

were for a time success-fully assimilated or ignored.

From

the late r6th century the most influential of these was the prolific atelier of

the Muslim Mughal emperors, who dominated northern India from their courts at

Agra, Delhi and Lahore. It was complemented by the distinct traditions

maintained by the independent Muslim sultanates of the Deccan until their

annexation by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the 168os. At the same time, a

great variety of local styles, influenced by Mughal example but fundamentally

indebted to older, indigenous traditions, flourished at the semi-independent

Hindu courts of the Rajputs. These formed two geographically separate groups,

in Rajasthan and Central India to the south and in the Punjab Hills to the

north. If the Rajasthani and Pahari (or 'Hill) schools did not often achieve or

seek the technical refinement of the best Mughal and Deccani painting, they

made up for it both in intensity of feeling and in their greater longevity.

Their relative isolation and closeness to folk roots enabled them to survive

the political disasters of the T 8th century and, in the case of some

Rajasthani schools, to continue into the mid- 9th century, or even later at a

few courts, where the undermining influences of Western art and photography

were for a time success-fully assimilated or ignored.

Painting Before the Mughal Period

The

painting of India's classical civilization (c.500 BC-1000 AD) has been almost

entirely destroyed by the climate, pests and later Muslim iconoclasm. Early

literary sources describe palaces, houses and temples as being abundantly

decorated with wall-paintings. Painting on wood or cloth was also widely

practised, and picture-making is one of the sixty-four polite arts enjoined on

the cultivated man or woman in the Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana. A glimpse of this

incalculable loss to world art is offered by the remains of wall-paintings at

the Buddhist cave-temples of Ajantamoo BC-500 AD). Their depictions of scenes

from the lives of the Buddha evoke an ideal world, peopled by aristocratic and

serenely graceful gods, men and women living in harmony with nature. The

artists' methods, which included naturalistic techniques of tonal modelling and

spatial recession, are recorded in extant manuals (shilpashastras).

The

painting of India's classical civilization (c.500 BC-1000 AD) has been almost

entirely destroyed by the climate, pests and later Muslim iconoclasm. Early

literary sources describe palaces, houses and temples as being abundantly

decorated with wall-paintings. Painting on wood or cloth was also widely

practised, and picture-making is one of the sixty-four polite arts enjoined on

the cultivated man or woman in the Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana. A glimpse of this

incalculable loss to world art is offered by the remains of wall-paintings at

the Buddhist cave-temples of Ajantamoo BC-500 AD). Their depictions of scenes

from the lives of the Buddha evoke an ideal world, peopled by aristocratic and

serenely graceful gods, men and women living in harmony with nature. The

artists' methods, which included naturalistic techniques of tonal modelling and

spatial recession, are recorded in extant manuals (shilpashastras).

The

later paintings at Ajanta, however, appear to stand at the end of the classical

tradition supported by the Gupta and Vakataka dynasties (fourth and fifth

centuries). In the following centuries a gradual regression occurred from

naturalistic, modelled forms to stylised outline drawing enclosing flat,

decorative colour areas. Something of the graceful quality of Ajanta painting

still remains in the earliest surviving illustrated palm-leaf manuscripts,

produced in the scriptoria of the great Buddhist teaching monasteries of

eastern India under the Pala dynasty in the 11th and 12th

centuries. Paintings of the Buddhas or of associated deities, either wrathful

or benign like the compassionate goddess Tara plate were introduced into the

sublimely metaphysical Buddhist wisdom texts not for illustration but for the

protection of the owner and the manuscript.

From

the early 13th century northern India was overrun by Turks and

Afghans from Central Asia, who established Muslim: dominance over all but the

far south of the sub-continent. With the destruction of the monasteries,

Buddhist culture all but disappeared in its homeland, and the Pala tradition

was carried on only in Nepal and Tibet. Hindu religious and secular culture

also suffered from the removal of royal patronage. The culture of the Muslim

sultans was Persian, and their taste in painting extended only to manuscript

illustration in Persianatc styles. During these lean early centuries of Muslim

rule, the native tradition of painting was largely kept alive by members of the

wealthy merchant classes of western India who were devotees of Jainism, an

ascetically inclined religion founded by Mahavira, a near-contemporary of the

Buddha, in the 6th century BC. Prosperous Jain laymen commonly

sought religious merit by commissioning illustrated copies of sacred texts for

presentation to monastic libraries. Huge numbers of stereotyped and sometimes

gaudily opulent series of illustrations were thus produced.

From

the early 13th century northern India was overrun by Turks and

Afghans from Central Asia, who established Muslim: dominance over all but the

far south of the sub-continent. With the destruction of the monasteries,

Buddhist culture all but disappeared in its homeland, and the Pala tradition

was carried on only in Nepal and Tibet. Hindu religious and secular culture

also suffered from the removal of royal patronage. The culture of the Muslim

sultans was Persian, and their taste in painting extended only to manuscript

illustration in Persianatc styles. During these lean early centuries of Muslim

rule, the native tradition of painting was largely kept alive by members of the

wealthy merchant classes of western India who were devotees of Jainism, an

ascetically inclined religion founded by Mahavira, a near-contemporary of the

Buddha, in the 6th century BC. Prosperous Jain laymen commonly

sought religious merit by commissioning illustrated copies of sacred texts for

presentation to monastic libraries. Huge numbers of stereotyped and sometimes

gaudily opulent series of illustrations were thus produced.

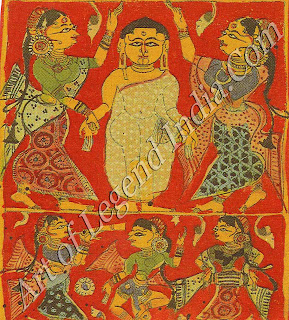

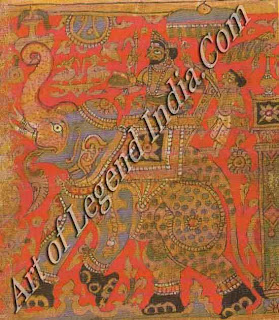

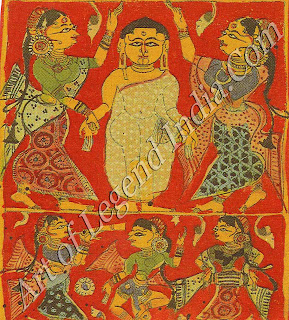

The

regression towards a linear, conceptual mode of representation was now

complete. One of the characteristic features of the style is the protrusion

into space of the further eye of the human face seen in profile. Nevertheless,

their wiry drawing, simplified colour schemes and profuse detail can give Jain

paintings an energy and charm of their own. The schematic and literal-minded

approach of the artists to their subject matter is seen in a lively

illustration, divided into upper and lower registers, of the ideally chaste

monk, who is unmoved by the beguilements of women.

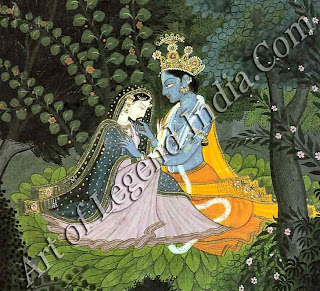

Jain

patronage thus preserved intact elements of a native style, which were by the

early 16th century to be revivified by artists working in a new and more

expressive idiom. During the 15th century a resurgence of popular

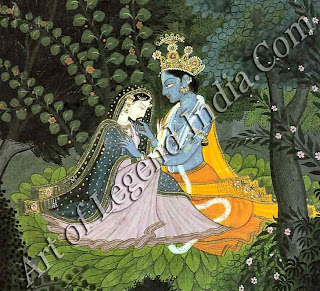

Hindu devotional cults had occurred throughout northern India, centred on the

incarnations of Vishnu as the hero Rama and, more particularly, as Krishna, the

youthful, dark-skinned cowherd god. Krishna's mythical exploits during his

childhood and youth spent in a village in the Braj country near Mathura

included the slaying of many demons and a tyrant king as well as various love

sports with the local milkmaids, among whom Radha became a preeminent figure.

Jain

patronage thus preserved intact elements of a native style, which were by the

early 16th century to be revivified by artists working in a new and more

expressive idiom. During the 15th century a resurgence of popular

Hindu devotional cults had occurred throughout northern India, centred on the

incarnations of Vishnu as the hero Rama and, more particularly, as Krishna, the

youthful, dark-skinned cowherd god. Krishna's mythical exploits during his

childhood and youth spent in a village in the Braj country near Mathura

included the slaying of many demons and a tyrant king as well as various love

sports with the local milkmaids, among whom Radha became a preeminent figure.

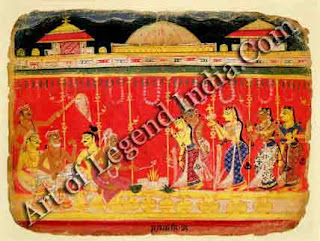

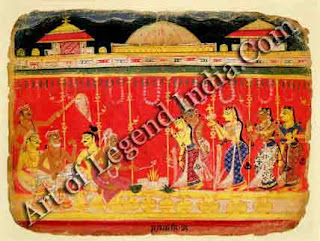

These episodes were celebrated in devotional verse in the Sanskrit and

vernacular literatures, and they also came to be represented in a vigorous,

widespread style of manuscript illustration. The patrons of this new

development appear to have been both the Vaishnavite merchant classes of the

Mathura region and, at a more refined level of production, the still

independent Hindu courts of the Rajputs, who had resisted Muslim incursions and

continued to rule the adjoining regions of Rajasthan and Central India. A page

from the most lively and inventive of the surviving manuscripts in the style

shows an enhanced spatial sense and fluency of drawing and a use of glowing colour

to create an atmosphere of elation appropriate to its subject, Krishna's

parents are shown standing before the sacrificial fire, on which the priest who

is marrying them pours ghee, while female attendants and male guests look on.

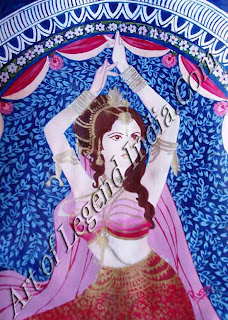

As

patrons of learning, literature, music and art, the Rajput rulers also

preserved and developed the secular traditions of classical Indian culture.

Manuscript illustrations of poetical texts were produced in the same style as

the devotional themes, and the two streams were in fact largely

indistinguishable.

As

patrons of learning, literature, music and art, the Rajput rulers also

preserved and developed the secular traditions of classical Indian culture.

Manuscript illustrations of poetical texts were produced in the same style as

the devotional themes, and the two streams were in fact largely

indistinguishable.

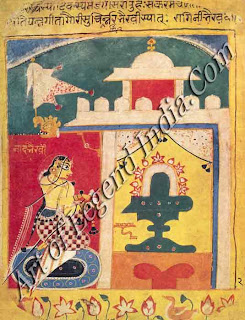

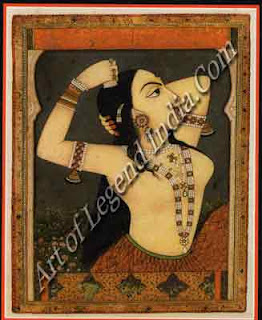

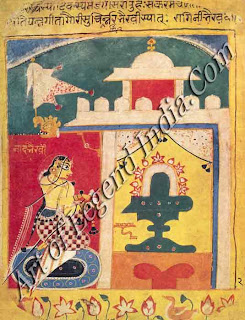

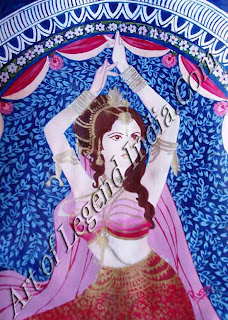

Down to the 19th century, Krishna subjects in

particular became closely associated with the imagery of poetical and

rhetorical works. Displaying the Indian passion for minute classification,

these enumerated the many different types of male and female lovers and their

emotional states, or, in the case of ragantala texts, evoked the essential

character of the ragas or musical modes in images of gods, ascetics, nobles,

ladies and animals in specific attitudes and configurations. In one of the

earliest surviving ragantala pictures the mode Bhairavi is described in the

verses above as a lady of fair complexion who worships Shiva in his litigant

(phallic) form with flowers, songs and cymbal accompaniment at a lakeside temple

near the sacred Mount Kailasa's As so often in Rajput pictures, there is a

mingling of the devotional and erotic sentiments, hinted at by the temple

finial in the form of a flag-bearing inakara, a mythical aquatic beast

emblematic of the love-god Kama.

In its allusive subject matter, bold drawing

and juxtaposition of broad areas of pure colour, this style of painting

anticipates the later work of the Rajasthani and Central Indian schools, whose

individual histories only begin to be clear from the early 17th century

onwards. However, their continuity from the earlier style is difficult to trace

precisely, for from the late 16th century Rajput patronage was both disrupted

and modified by the coming of the Mughals, the last and most powerful of the

Muslim dynasties of northern India.

Writer – Andrew Topsfield

A

remarkable flowering of regional schools of painting took place at the Muslim

and Hindu courts of northern India and the Deccan between the 16th and

19th centuries. Today this enormous production of pictures and illustrated

manuscripts has been largely dispersed by the disinherited princely families

and is found in public and private collections throughout the world. Even to

modern man, living in Babel of visual information, the appeal of Indian

pictures is immediate. They were made above all to delight the eye by their

rich colour harmonies and fluent clarity of line and, by keeping in each case

to a traditional range of expressive conventions, to impart mainly auspicious

or pleasurable sentiments, whether of royal grandeur, devotional wonder or a

refined eroticism. It was an art inseparable from the courtly milieu and its

preoccupations both with religious, literary and musical culture and with the

self-regarding imagery of power and display.

A

remarkable flowering of regional schools of painting took place at the Muslim

and Hindu courts of northern India and the Deccan between the 16th and

19th centuries. Today this enormous production of pictures and illustrated

manuscripts has been largely dispersed by the disinherited princely families

and is found in public and private collections throughout the world. Even to

modern man, living in Babel of visual information, the appeal of Indian

pictures is immediate. They were made above all to delight the eye by their

rich colour harmonies and fluent clarity of line and, by keeping in each case

to a traditional range of expressive conventions, to impart mainly auspicious

or pleasurable sentiments, whether of royal grandeur, devotional wonder or a

refined eroticism. It was an art inseparable from the courtly milieu and its

preoccupations both with religious, literary and musical culture and with the

self-regarding imagery of power and display.  From

the late r6th century the most influential of these was the prolific atelier of

the Muslim Mughal emperors, who dominated northern India from their courts at

Agra, Delhi and Lahore. It was complemented by the distinct traditions

maintained by the independent Muslim sultanates of the Deccan until their

annexation by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the 168os. At the same time, a

great variety of local styles, influenced by Mughal example but fundamentally

indebted to older, indigenous traditions, flourished at the semi-independent

Hindu courts of the Rajputs. These formed two geographically separate groups,

in Rajasthan and Central India to the south and in the Punjab Hills to the

north. If the Rajasthani and Pahari (or 'Hill) schools did not often achieve or

seek the technical refinement of the best Mughal and Deccani painting, they

made up for it both in intensity of feeling and in their greater longevity.

Their relative isolation and closeness to folk roots enabled them to survive

the political disasters of the T 8th century and, in the case of some

Rajasthani schools, to continue into the mid- 9th century, or even later at a

few courts, where the undermining influences of Western art and photography

were for a time success-fully assimilated or ignored.

From

the late r6th century the most influential of these was the prolific atelier of

the Muslim Mughal emperors, who dominated northern India from their courts at

Agra, Delhi and Lahore. It was complemented by the distinct traditions

maintained by the independent Muslim sultanates of the Deccan until their

annexation by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the 168os. At the same time, a

great variety of local styles, influenced by Mughal example but fundamentally

indebted to older, indigenous traditions, flourished at the semi-independent

Hindu courts of the Rajputs. These formed two geographically separate groups,

in Rajasthan and Central India to the south and in the Punjab Hills to the

north. If the Rajasthani and Pahari (or 'Hill) schools did not often achieve or

seek the technical refinement of the best Mughal and Deccani painting, they

made up for it both in intensity of feeling and in their greater longevity.

Their relative isolation and closeness to folk roots enabled them to survive

the political disasters of the T 8th century and, in the case of some

Rajasthani schools, to continue into the mid- 9th century, or even later at a

few courts, where the undermining influences of Western art and photography

were for a time success-fully assimilated or ignored.  The

painting of India's classical civilization (c.500 BC-1000 AD) has been almost

entirely destroyed by the climate, pests and later Muslim iconoclasm. Early

literary sources describe palaces, houses and temples as being abundantly

decorated with wall-paintings. Painting on wood or cloth was also widely

practised, and picture-making is one of the sixty-four polite arts enjoined on

the cultivated man or woman in the Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana. A glimpse of this

incalculable loss to world art is offered by the remains of wall-paintings at

the Buddhist cave-temples of Ajantamoo BC-500 AD). Their depictions of scenes

from the lives of the Buddha evoke an ideal world, peopled by aristocratic and

serenely graceful gods, men and women living in harmony with nature. The

artists' methods, which included naturalistic techniques of tonal modelling and

spatial recession, are recorded in extant manuals (shilpashastras).

The

painting of India's classical civilization (c.500 BC-1000 AD) has been almost

entirely destroyed by the climate, pests and later Muslim iconoclasm. Early

literary sources describe palaces, houses and temples as being abundantly

decorated with wall-paintings. Painting on wood or cloth was also widely

practised, and picture-making is one of the sixty-four polite arts enjoined on

the cultivated man or woman in the Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana. A glimpse of this

incalculable loss to world art is offered by the remains of wall-paintings at

the Buddhist cave-temples of Ajantamoo BC-500 AD). Their depictions of scenes

from the lives of the Buddha evoke an ideal world, peopled by aristocratic and

serenely graceful gods, men and women living in harmony with nature. The

artists' methods, which included naturalistic techniques of tonal modelling and

spatial recession, are recorded in extant manuals (shilpashastras).  From

the early 13th century northern India was overrun by Turks and

Afghans from Central Asia, who established Muslim: dominance over all but the

far south of the sub-continent. With the destruction of the monasteries,

Buddhist culture all but disappeared in its homeland, and the Pala tradition

was carried on only in Nepal and Tibet. Hindu religious and secular culture

also suffered from the removal of royal patronage. The culture of the Muslim

sultans was Persian, and their taste in painting extended only to manuscript

illustration in Persianatc styles. During these lean early centuries of Muslim

rule, the native tradition of painting was largely kept alive by members of the

wealthy merchant classes of western India who were devotees of Jainism, an

ascetically inclined religion founded by Mahavira, a near-contemporary of the

Buddha, in the 6th century BC. Prosperous Jain laymen commonly

sought religious merit by commissioning illustrated copies of sacred texts for

presentation to monastic libraries. Huge numbers of stereotyped and sometimes

gaudily opulent series of illustrations were thus produced.

From

the early 13th century northern India was overrun by Turks and

Afghans from Central Asia, who established Muslim: dominance over all but the

far south of the sub-continent. With the destruction of the monasteries,

Buddhist culture all but disappeared in its homeland, and the Pala tradition

was carried on only in Nepal and Tibet. Hindu religious and secular culture

also suffered from the removal of royal patronage. The culture of the Muslim

sultans was Persian, and their taste in painting extended only to manuscript

illustration in Persianatc styles. During these lean early centuries of Muslim

rule, the native tradition of painting was largely kept alive by members of the

wealthy merchant classes of western India who were devotees of Jainism, an

ascetically inclined religion founded by Mahavira, a near-contemporary of the

Buddha, in the 6th century BC. Prosperous Jain laymen commonly

sought religious merit by commissioning illustrated copies of sacred texts for

presentation to monastic libraries. Huge numbers of stereotyped and sometimes

gaudily opulent series of illustrations were thus produced.  Jain

patronage thus preserved intact elements of a native style, which were by the

early 16th century to be revivified by artists working in a new and more

expressive idiom. During the 15th century a resurgence of popular

Hindu devotional cults had occurred throughout northern India, centred on the

incarnations of Vishnu as the hero Rama and, more particularly, as Krishna, the

youthful, dark-skinned cowherd god. Krishna's mythical exploits during his

childhood and youth spent in a village in the Braj country near Mathura

included the slaying of many demons and a tyrant king as well as various love

sports with the local milkmaids, among whom Radha became a preeminent figure.

Jain

patronage thus preserved intact elements of a native style, which were by the

early 16th century to be revivified by artists working in a new and more

expressive idiom. During the 15th century a resurgence of popular

Hindu devotional cults had occurred throughout northern India, centred on the

incarnations of Vishnu as the hero Rama and, more particularly, as Krishna, the

youthful, dark-skinned cowherd god. Krishna's mythical exploits during his

childhood and youth spent in a village in the Braj country near Mathura

included the slaying of many demons and a tyrant king as well as various love

sports with the local milkmaids, among whom Radha became a preeminent figure.  As

patrons of learning, literature, music and art, the Rajput rulers also

preserved and developed the secular traditions of classical Indian culture.

Manuscript illustrations of poetical texts were produced in the same style as

the devotional themes, and the two streams were in fact largely

indistinguishable.

As

patrons of learning, literature, music and art, the Rajput rulers also

preserved and developed the secular traditions of classical Indian culture.

Manuscript illustrations of poetical texts were produced in the same style as

the devotional themes, and the two streams were in fact largely

indistinguishable.

Thanks for sharing about Traditional Painting. Your content is realy informative for us......

Indian Traditional Paintings

Indian Painting

Traditional Paintings

Traditional Painting

Indian Traditional Painting

Traditional Paintings

Traditional Painting