India

has a tradition of love poetry stretching back almost to the age of the Vedas.

In its earlier phase it found expression in Sanskrit and later on in Prakrit

and Hindi. The love charms of the Atharva are said to mark the beginning of

erotic poetry. In the Rigveda, Usha, the goddess of Dawn, is compared to a

maiden who unveils her bosom to her lover. This was a period when Sanskrit was

the living language of a virile people and had not fossilised into a language

of the learned. In Valmikes Ramayana, the dawn is treated as a loving maiden:

`Ah that the enamoured twilight should lay aside her garment of sky, now that

the stars are quickened to life by the touch of the rays of the dancing moon'.

India

has a tradition of love poetry stretching back almost to the age of the Vedas.

In its earlier phase it found expression in Sanskrit and later on in Prakrit

and Hindi. The love charms of the Atharva are said to mark the beginning of

erotic poetry. In the Rigveda, Usha, the goddess of Dawn, is compared to a

maiden who unveils her bosom to her lover. This was a period when Sanskrit was

the living language of a virile people and had not fossilised into a language

of the learned. In Valmikes Ramayana, the dawn is treated as a loving maiden:

`Ah that the enamoured twilight should lay aside her garment of sky, now that

the stars are quickened to life by the touch of the rays of the dancing moon'.

Among

the earliest specimens of Sanskrit kavya are the works of the Buddhist poet and

philosopher, Asvaghosha (c. A.D. 100). His poem, the Saundarananda, deals with

the legend of the conversion of his half-brother, Nanda, by the Buddha. In

canto iii, the poet describes the beauty of Sundari, Nanda's wife and compares

her to a lotus pond, with her laughter for the swans, her eyes for the bees,

and her swelling breasts for the uprising lotus buds. The perfection of her

union with Nanda, he describes as of the night with the moon.

The

Hindu Sritigara literature, both in Sanskrit and Hindi, has its roots in

Bharata's Natyagastra, a treatise on dramaturgy. Poetry, music, and dance were

necessary components of a Hindu drama, and as such the book deals also with poetics,

music and the language of gesture. According to Manmohan Ghosh, the available

text of the Natyagastra existed in the second century A.D., while the tradition

which it recorded may go back to a period as early as 100 B.C. It is composed

in verse in the form of a dialogue between Bharata and some ancient sages.

Apart from Sanskrit, the Natyagastra also gives examples of Prakrit verses. It

is the earliest writing on poetics, contains discussion on figures of speech,

mentions the qualities and faults of a composition, and describes varieties of

metre. In relation to ars amatoria it mentions Kamasasra and Kamatantra, but

there is no reference to Vatsyayana's Kamasatra, which was composed much later.

The

Hindu Sritigara literature, both in Sanskrit and Hindi, has its roots in

Bharata's Natyagastra, a treatise on dramaturgy. Poetry, music, and dance were

necessary components of a Hindu drama, and as such the book deals also with poetics,

music and the language of gesture. According to Manmohan Ghosh, the available

text of the Natyagastra existed in the second century A.D., while the tradition

which it recorded may go back to a period as early as 100 B.C. It is composed

in verse in the form of a dialogue between Bharata and some ancient sages.

Apart from Sanskrit, the Natyagastra also gives examples of Prakrit verses. It

is the earliest writing on poetics, contains discussion on figures of speech,

mentions the qualities and faults of a composition, and describes varieties of

metre. In relation to ars amatoria it mentions Kamasasra and Kamatantra, but

there is no reference to Vatsyayana's Kamasatra, which was composed much later.

The

doctrine of rasa or flavor, and bhavas or emotions, was also enunciated in the

Natyasastra. As the tastes of food are produced by salt, spices or sugar, the

dominant states (sthayibhava), when they come together with other states (bhava)

become sentiments. As an epicurean tastes food by eating, so learned people

taste in their mind the dominant states or sentiments. The aesthetic experience

is described by Bharata as the tasting of flavour (rasasvadana), the taster is

rasika, and the work of art is rasavant. Of the eight emotional conditions, the

sringarrasa, or erotic flavour, whose underlying emotions are love or desire,

is the most important. It is the erotic sentiment which is the basis of the

most beautiful art, whether poetry or painting.

The

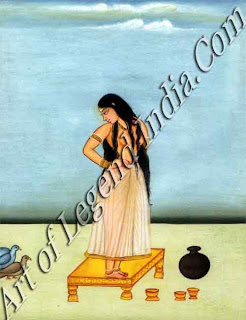

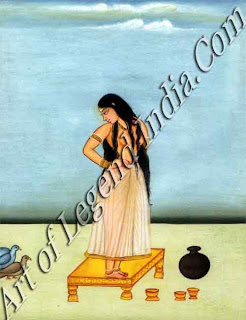

subtle classification of woman according to mood, sentiment and situation,

called mayika-bheda, which was refined and elaborated by a succession of poets

and rhetoricians, also has its origin in the Natyasastra. The eight-fold

classification of heroines or nayikas is given, and female messengers, their

qualities and functions are described. This is followed by the theme of mana

and mana-mochana.

The

subtle classification of woman according to mood, sentiment and situation,

called mayika-bheda, which was refined and elaborated by a succession of poets

and rhetoricians, also has its origin in the Natyasastra. The eight-fold

classification of heroines or nayikas is given, and female messengers, their

qualities and functions are described. This is followed by the theme of mana

and mana-mochana.

Sanskrit

was no longer a spoken language by the close of the first century A.D. The

languages of the people were Prakrits which at later stages evolved into the

modern regional languages. Lyric poetry found its first and best expression in

the Prakrits. 'One reason for the excellence of these little poems', says

Grierson, 'is their almost invariable truth to nature, and the cause of this is

that from the first they have been rooted in village life and language, and not

in the pandit-fostering circles of the towns." The oldest and most admired

anthology is the Sapta-sataka or the Seven Centuries of Hala, who flourished

somewhere during the period A.D. 200 to 450 in Maharashtra. There are charming

genre pictures, describing the farmers, hunters, cowherds and cowherdesses in

these Prakrits lyrics. Hala's poetry is close to the soil and the people of the

land. There are vivid pictures of nature and the seasons. Bees hover over

flowers, peacocks enjoy the rain-showers while the female antelope seeks her

mate longingly. The grief of a woman waiting for her lover is thus described:

"Waiting for you, the first half of the

night

passed like a

moment.

The

rest was like a year,

for

I was sunk in grief."

The

prevailing tone is gentle and pleasing', observes Keith, 'simple love set among

simple scenes, fostered by the seasons, for even winter brings lovers close

together, just as a rain-storm drives them to shelter with each other. The

maiden begs the moon to touch her with the rays which have touched her beloved;

she begs the night to stay for ever, since the morn is to see her beloved's

departure.

The

prevailing tone is gentle and pleasing', observes Keith, 'simple love set among

simple scenes, fostered by the seasons, for even winter brings lovers close

together, just as a rain-storm drives them to shelter with each other. The

maiden begs the moon to touch her with the rays which have touched her beloved;

she begs the night to stay for ever, since the morn is to see her beloved's

departure.

Sanskrit,

though it continued as the language of literature for a long time, reached its

zenith in the period from the fifth to seventh centuries. In the sensuous poems

of India's greatest poet, Kalidasa (fl. 5th century A.D.), Sanskrit romantic

poetry reaches its most elegant expression.

In the Sringarasataka

or Century of Love of Bhartrihari (fl. 7th century A.D.), are brilliant

pictures of the beauty of women, and of the joys of love in union. There are

two other centuries of verses by him, viz. the Century of Worldly Wisdom, and

the Century of Renunciation. The titles of his collections of poems also

reflect the fickleness of the author who seven times became a Buddhist monk and

seven times relapsed into worldly life. He regards woman as poison enclosed in

a shell of sweetness, and considers her beauty a snare which distracts man from

his true goal, which is the calm of meditation. He ultimately comes to the

conclusion that the best life is one of solitude and contemplation:

"When I was ignorant in

the dark night of passion

thought the world completely made of women,

but

now my eyes are cleansed with the salve of wisdom,

and

my clear vision sees only God in everything."

In the

seventh century flourished Mayura, who was a contemporary of Harsha-vardhana.

He thus describes a young woman who is returning after a night's revel with her

lover: 'Who is this timid gazelle, burdened with firm swelling breasts,

slender-waisted and wild-eyed, who hath left the startled herd? She goeth in

sport as if fallen from the temples of an elephant in rut. Seeing her beauty

even an old man turns to thoughts of love."

In the

seventh century flourished Mayura, who was a contemporary of Harsha-vardhana.

He thus describes a young woman who is returning after a night's revel with her

lover: 'Who is this timid gazelle, burdened with firm swelling breasts,

slender-waisted and wild-eyed, who hath left the startled herd? She goeth in

sport as if fallen from the temples of an elephant in rut. Seeing her beauty

even an old man turns to thoughts of love."

Amaru

who flourished between 650 and 750 A.D. describes the relation of lovers in his

Century of Stanzas, the Amarusataka. The relations of lovers, which later

writers of poetics described in the form of Ashtanayikas, and Mana are

delightfully narrated in his gay verses.

Vatsyayana's

Kamasutra, which is probably older than Kalidasa, was studied eagerly by the

Sanskrit poets along with grammar, lexicography and poetics. Sriharsha, the

author of the Naishadhacharita, who flourished in the second half of the

twelfth century at Kanauj, shows a good knowledge of the Kamasutra, while

describing the married bliss of Nala and Damayanti. The Vaishnava Movement The

eleventh century witnessed a great popularity of the Vaishnava movement. In the

field of literature, Prakrits, and later on regional languages, replaced

Sanskrit. The herald of the new dawn was a South Indian saint, Randnuja

(1017-1137), who is regarded as one of the great apostles of Vaishnavism. He

was born in the village of Sri-perambudur in Madras State. He mastered the

Vedas, and wrote commentaries on the Vedanta-sutras and the Bhagavad-Gita. He

popularised the worship of Vishnu as the Supreme Being.

Jayadeva,

the author of the Gita Govinda, and the court poet of Lakshmanasena

(1179-1205), was the earliest poet of Vaishnavism in Bengal. He wrote

ecstatically of the love of Radha and Krishna, in which was imaged the love of

the soul for God, personified in Krishna. The poem is regarded as an allegory

of the soul striving to escape the allurement of the senses to find peace in

mystical union with God. Hence arose a doctrine of passionate personal

devotion, bhakti or faith towards an incarnate deity in the form of Krishna and

absolute surrender of self to the divine will.

It was

Eastern India, the provinces of Bihar and Bengal, which became an important

centre of the Radha-Krishna cult. Vidydpati (fl. 1400-1470), the poet of Bihar,

wrote in the sweet Maithili dialect on the loves of Radha and Krishna. He was

the most famous of the Vaishnava poets of Eastern India. He was inspired by the

beauty of Lacchima Devi, queen of his patron, Raja Sib Singh of Mithila in

Bihar. There is a tradition that the Emperor Akbar summoned Sib Singh to Delhi

for some offence, and that Vidyapati obtained his patron's release by an

exhibition of clairvoyance.

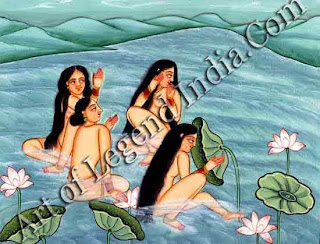

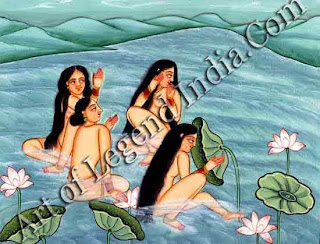

The incident is thus narrated by Grierson: 'The

emperor locked him up in a wooden box, and sent a number of courtesans of the

town to bathe in the river. When all was over he released him and asked him to

describe what had occurred, when Vidyapati immediately recited impromptu one of

the most charming of his sonnets, which has come down to us, describing a

beautiful girl at her bath. Astonished at his power, the emperor granted his

petition to release Sib Singh. In the love-sonnets of the great master-singer

of Mithila we find sacredness wedded to sensuous joy. There are vivid

word-pictures of the love of Radha and Krishna painted in a musical language.

Coming direct from the heart they remind us that there is nothing so beautiful

and touching as sincerity and simplicity.

The incident is thus narrated by Grierson: 'The

emperor locked him up in a wooden box, and sent a number of courtesans of the

town to bathe in the river. When all was over he released him and asked him to

describe what had occurred, when Vidyapati immediately recited impromptu one of

the most charming of his sonnets, which has come down to us, describing a

beautiful girl at her bath. Astonished at his power, the emperor granted his

petition to release Sib Singh. In the love-sonnets of the great master-singer

of Mithila we find sacredness wedded to sensuous joy. There are vivid

word-pictures of the love of Radha and Krishna painted in a musical language.

Coming direct from the heart they remind us that there is nothing so beautiful

and touching as sincerity and simplicity.

A

contemporary Of Vidyapati was Chandi Das who lived at Nannara in Birbhum

district of West Bengal. 'Representing the flow and ardour of impassioned

love', says Dineshchandra Sen, 'he became the harbinger of a new age which soon

after dawned on our moral and spiritual life and charged it with the white heat

of its emotional bliss II His Krishtiakirtana describes the love of Radha' and

Krishna in different phases. Chandi Das had fallen in love with a washerwoman,

Rami by name, and in describing the physical charm of Radha, and her behaviour,

he was drawing upon his own experience. With what passion he describes the

pursuit of Radha by Krishna amidst market places, groves and the gay scenery

along the bank of the Yamunal In the poems of Chandi Ds, sensuous emotions are

sublimated into spiritual delight. The pleasures of the senses find an outlet

in mystic ecstasy.

Writer – M.S. Randhawa

India

has a tradition of love poetry stretching back almost to the age of the Vedas.

In its earlier phase it found expression in Sanskrit and later on in Prakrit

and Hindi. The love charms of the Atharva are said to mark the beginning of

erotic poetry. In the Rigveda, Usha, the goddess of Dawn, is compared to a

maiden who unveils her bosom to her lover. This was a period when Sanskrit was

the living language of a virile people and had not fossilised into a language

of the learned. In Valmikes Ramayana, the dawn is treated as a loving maiden:

`Ah that the enamoured twilight should lay aside her garment of sky, now that

the stars are quickened to life by the touch of the rays of the dancing moon'.

India

has a tradition of love poetry stretching back almost to the age of the Vedas.

In its earlier phase it found expression in Sanskrit and later on in Prakrit

and Hindi. The love charms of the Atharva are said to mark the beginning of

erotic poetry. In the Rigveda, Usha, the goddess of Dawn, is compared to a

maiden who unveils her bosom to her lover. This was a period when Sanskrit was

the living language of a virile people and had not fossilised into a language

of the learned. In Valmikes Ramayana, the dawn is treated as a loving maiden:

`Ah that the enamoured twilight should lay aside her garment of sky, now that

the stars are quickened to life by the touch of the rays of the dancing moon'.  The

Hindu Sritigara literature, both in Sanskrit and Hindi, has its roots in

Bharata's Natyagastra, a treatise on dramaturgy. Poetry, music, and dance were

necessary components of a Hindu drama, and as such the book deals also with poetics,

music and the language of gesture. According to Manmohan Ghosh, the available

text of the Natyagastra existed in the second century A.D., while the tradition

which it recorded may go back to a period as early as 100 B.C. It is composed

in verse in the form of a dialogue between Bharata and some ancient sages.

Apart from Sanskrit, the Natyagastra also gives examples of Prakrit verses. It

is the earliest writing on poetics, contains discussion on figures of speech,

mentions the qualities and faults of a composition, and describes varieties of

metre. In relation to ars amatoria it mentions Kamasasra and Kamatantra, but

there is no reference to Vatsyayana's Kamasatra, which was composed much later.

The

Hindu Sritigara literature, both in Sanskrit and Hindi, has its roots in

Bharata's Natyagastra, a treatise on dramaturgy. Poetry, music, and dance were

necessary components of a Hindu drama, and as such the book deals also with poetics,

music and the language of gesture. According to Manmohan Ghosh, the available

text of the Natyagastra existed in the second century A.D., while the tradition

which it recorded may go back to a period as early as 100 B.C. It is composed

in verse in the form of a dialogue between Bharata and some ancient sages.

Apart from Sanskrit, the Natyagastra also gives examples of Prakrit verses. It

is the earliest writing on poetics, contains discussion on figures of speech,

mentions the qualities and faults of a composition, and describes varieties of

metre. In relation to ars amatoria it mentions Kamasasra and Kamatantra, but

there is no reference to Vatsyayana's Kamasatra, which was composed much later.

The

subtle classification of woman according to mood, sentiment and situation,

called mayika-bheda, which was refined and elaborated by a succession of poets

and rhetoricians, also has its origin in the Natyasastra. The eight-fold

classification of heroines or nayikas is given, and female messengers, their

qualities and functions are described. This is followed by the theme of mana

and mana-mochana.

The

subtle classification of woman according to mood, sentiment and situation,

called mayika-bheda, which was refined and elaborated by a succession of poets

and rhetoricians, also has its origin in the Natyasastra. The eight-fold

classification of heroines or nayikas is given, and female messengers, their

qualities and functions are described. This is followed by the theme of mana

and mana-mochana.  The

prevailing tone is gentle and pleasing', observes Keith, 'simple love set among

simple scenes, fostered by the seasons, for even winter brings lovers close

together, just as a rain-storm drives them to shelter with each other. The

maiden begs the moon to touch her with the rays which have touched her beloved;

she begs the night to stay for ever, since the morn is to see her beloved's

departure.

The

prevailing tone is gentle and pleasing', observes Keith, 'simple love set among

simple scenes, fostered by the seasons, for even winter brings lovers close

together, just as a rain-storm drives them to shelter with each other. The

maiden begs the moon to touch her with the rays which have touched her beloved;

she begs the night to stay for ever, since the morn is to see her beloved's

departure. In the

seventh century flourished Mayura, who was a contemporary of Harsha-vardhana.

He thus describes a young woman who is returning after a night's revel with her

lover: 'Who is this timid gazelle, burdened with firm swelling breasts,

slender-waisted and wild-eyed, who hath left the startled herd? She goeth in

sport as if fallen from the temples of an elephant in rut. Seeing her beauty

even an old man turns to thoughts of love."

In the

seventh century flourished Mayura, who was a contemporary of Harsha-vardhana.

He thus describes a young woman who is returning after a night's revel with her

lover: 'Who is this timid gazelle, burdened with firm swelling breasts,

slender-waisted and wild-eyed, who hath left the startled herd? She goeth in

sport as if fallen from the temples of an elephant in rut. Seeing her beauty

even an old man turns to thoughts of love."  The incident is thus narrated by Grierson: 'The

emperor locked him up in a wooden box, and sent a number of courtesans of the

town to bathe in the river. When all was over he released him and asked him to

describe what had occurred, when Vidyapati immediately recited impromptu one of

the most charming of his sonnets, which has come down to us, describing a

beautiful girl at her bath. Astonished at his power, the emperor granted his

petition to release Sib Singh. In the love-sonnets of the great master-singer

of Mithila we find sacredness wedded to sensuous joy. There are vivid

word-pictures of the love of Radha and Krishna painted in a musical language.

Coming direct from the heart they remind us that there is nothing so beautiful

and touching as sincerity and simplicity.

The incident is thus narrated by Grierson: 'The

emperor locked him up in a wooden box, and sent a number of courtesans of the

town to bathe in the river. When all was over he released him and asked him to

describe what had occurred, when Vidyapati immediately recited impromptu one of

the most charming of his sonnets, which has come down to us, describing a

beautiful girl at her bath. Astonished at his power, the emperor granted his

petition to release Sib Singh. In the love-sonnets of the great master-singer

of Mithila we find sacredness wedded to sensuous joy. There are vivid

word-pictures of the love of Radha and Krishna painted in a musical language.

Coming direct from the heart they remind us that there is nothing so beautiful

and touching as sincerity and simplicity.

0 Response to "The Literary and Religious Background of painting"

Post a Comment