In 1526

Babur, a minor prince from Transoxiana descended from both Tamerlane and

Chingiz Khan, culminated a lifetime of restless wanderings and short-lived

conquests by invading India. He founded a dynasty whose autocratic power and

luxurious display became proverbial as far away as England. Although its

decline was to be lengthy, it endured in name at least until the banishment of

the last Emperor by the British in 1858. For much of this period the cultural

interests and fashions of the imperial court exercised a pervasive influence

throughout the provinces, and not least on the art of painting.

In 1526

Babur, a minor prince from Transoxiana descended from both Tamerlane and

Chingiz Khan, culminated a lifetime of restless wanderings and short-lived

conquests by invading India. He founded a dynasty whose autocratic power and

luxurious display became proverbial as far away as England. Although its

decline was to be lengthy, it endured in name at least until the banishment of

the last Emperor by the British in 1858. For much of this period the cultural

interests and fashions of the imperial court exercised a pervasive influence

throughout the provinces, and not least on the art of painting.

Babur

himself died in 1530, soon after his conquest. He is not known to have

patronised painting during his turbulent career, but he did leave behind a

remarkable volume of memoirs, whose observations of man and nature reveal an

original and inquiring mind. During the reign of his bookish and ineffectual

son Humayun (153o-56) the still insecure empire was lost for a time to the

Pathan chief Sher Shah. Humayun was driven into exile at the court of Shah

Tahmasp of Persia, who, after a carefree youth distinguished by inspired

artistic patronage, was turning towards religious orthodoxy and a greater

attention to matters of state. Humayun was thus able to take two of the finest

Persian painters, Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd us-Samad, into his service. They

accompanied him on his re-turn to Delhi in 1555, where he died only a few

months later after a fall on his library staircase.

The

achievement of consolidating the empire and shaping its distinctive cultural

traditions belonged to Akbar (1556-1605), the third and greatest of the Mughal

emperors. He possessed not only the mental acuteness of Babur but an

all-embracing imperial vision and colossal physical energy with which to fulfil

it. By arms and diplomacy he extended the empire and made allies of the

powerful Rajputs. More than any earlier Muslim ruler, he had a receptive and

tolerant intellect. Many of his generals, courtiers, wives, poets and artists

were Hindus. His strong religious experiences led him to an open-minded debate

with representatives of all the known faiths, including Zoroastrians, Jews and

Jesuit priests. Disappointed by the animosity of these clerics, he typically

chose to found an eclectic and short-lived religion centred on his own person.

Painting

at Akbar's court reflected a similar forcible and dynamic synthesis between the

disparate cultures of Persia, India and Europe. Akbar had himself received

training from his father's two Persian masters, but the delicate refinement of

the Safavid manner did not satisfy his youthful exuberance.

Early in his reign

he set the two Persians to direct a newly recruited studio that grew to some

two hundred native artists. Under his constant supervision the early Mughal

style was thus formed from the fusion of Persian elegance and technique with

the Indian vitality and feeling for natural forms admired by Akbar. The

studio's most grandiose project, taking fifteen years to complete, was a series

of 1400 large illustrations on cloth to the romance of Amir Hamza, a prolix but

action-packed adventure story which was a favourite of the young Akbar.

Accord-ing to one Mughal historian he would himself act as a story-teller,

narrating Hainza's adventures to the inmates of his zenana (harem). In a

typical, the decorative Persian tile patterns and arabesques

stand in contrast to the vigorously painted trees, rocks, gesticulating figures

and gory victims of the leering dragon.

Early in his reign

he set the two Persians to direct a newly recruited studio that grew to some

two hundred native artists. Under his constant supervision the early Mughal

style was thus formed from the fusion of Persian elegance and technique with

the Indian vitality and feeling for natural forms admired by Akbar. The

studio's most grandiose project, taking fifteen years to complete, was a series

of 1400 large illustrations on cloth to the romance of Amir Hamza, a prolix but

action-packed adventure story which was a favourite of the young Akbar.

Accord-ing to one Mughal historian he would himself act as a story-teller,

narrating Hainza's adventures to the inmates of his zenana (harem). In a

typical, the decorative Persian tile patterns and arabesques

stand in contrast to the vigorously painted trees, rocks, gesticulating figures

and gory victims of the leering dragon.

By the

time of the Hanizanama's completion in the late 157os, the Akbari style was

reaching its maturity. A stream of smaller and less copiously illustrated

manuscripts of Persian prose and verse classics was produced in a blander but

more integrated idiom. In the last twenty years of Akbar's reign his interest

turned to illustrated histories of his own life and those of his Timurid

ancestors. At least five copies of Babur's memoirs were made, as well as three

of the Akbarnama, Abtel Fazl's official history of his reign. As unequivocal

propaganda, these and other commissions formed part of his imperial design, for

they documented and legitimised what was in Indian terms still only a parvenu

dynasty. The artists were more than ever required to record the court life

around them in a spirit of dramatic realism. It is unlikely that the painter

Khem Karan would have witnessed the siege of the Rajput fortress of Ranthainbor

some twenty years previously, but his portrayal of Akbar, dressed in white,

directing the attack from a promontory set against a hazy sky is a convincing

presentation of the event.

That this realism was to some extent based on a

selective study of European models is shown by an illustration to the

Harivamsa, one of the Hindu mythological texts which Akbar had ordered Badauni

to translate into Persian, to that scholar's pious disgust. Krishna sweeps down

on the bird Garuda to triumph over Indra on his elephant, watched by gods and

celestial beings. The billowing clouds and swirling draperies have Baroque

antecedents, while the coastal landscape with a European boat derives from

Flemish art. Abu'l Fazl, besides echoing his master's praise of Hindu artists,

whose 'pictures surpass our conception of things', refers also to 'the

wonderful works of the European painters, who have attained world-wide fame'.

He more-over tells us of an album prepared for Akbar which contained portraits

of himself and his courtiers. This was the first time in Indian art that

portraiture of the Western type, treating its subject as an individual

character rather than as a socially or poetically determined type, had been so

systematically pursued.

That this realism was to some extent based on a

selective study of European models is shown by an illustration to the

Harivamsa, one of the Hindu mythological texts which Akbar had ordered Badauni

to translate into Persian, to that scholar's pious disgust. Krishna sweeps down

on the bird Garuda to triumph over Indra on his elephant, watched by gods and

celestial beings. The billowing clouds and swirling draperies have Baroque

antecedents, while the coastal landscape with a European boat derives from

Flemish art. Abu'l Fazl, besides echoing his master's praise of Hindu artists,

whose 'pictures surpass our conception of things', refers also to 'the

wonderful works of the European painters, who have attained world-wide fame'.

He more-over tells us of an album prepared for Akbar which contained portraits

of himself and his courtiers. This was the first time in Indian art that

portraiture of the Western type, treating its subject as an individual

character rather than as a socially or poetically determined type, had been so

systematically pursued.

In the

reign of Jahangir (16o5-27) the imperial studio was reduced to an elite group

of the best painters, who attended the Emperor both in court and camp to carry

out his commissions. Manuscript illustration gave way to the production of fine

individual pictures, whose subject matter reflected Jahangir's enthusiasms and

foibles. Jahangir was a fickle character, capable both of generosity and

cruelty. Inheriting a well established empire, he never developed Akbar's gifts

as a statesman, and as his prodigious consumption of opium and alcohol

gradually enfeebled him, the administration passed out of his hands. He also

lacked Akbar's profound religious sense, being guided instead by a highly

developed aestheticism. As a connoisseur of the arts, he boasts justifiably in

his memoirs of his ability to distinguish even tiny details painted by

different artists.

He was also passionately curious about the forms and behavior

of plants and animals, and it has been remarked that he might have been a

better and happier man as the head of a natural history museum. When in 1612 a

turkey cock was brought in a consignment of rarities purchased from the

Portuguese in Goa, Jahangir as usual wrote up his observations, being

particularly fascinated by its head and neck: 'like a chameleon it constantly

changes colour'. His flower and animal artist, Mansur, known as 'Wonder of the

Age', recorded the new specimen, rendering each feather and fold of skin with

minute brushwork, against a plain background relieved only by (discoloured)

streaks and a conventional row of flowers.

He was also passionately curious about the forms and behavior

of plants and animals, and it has been remarked that he might have been a

better and happier man as the head of a natural history museum. When in 1612 a

turkey cock was brought in a consignment of rarities purchased from the

Portuguese in Goa, Jahangir as usual wrote up his observations, being

particularly fascinated by its head and neck: 'like a chameleon it constantly

changes colour'. His flower and animal artist, Mansur, known as 'Wonder of the

Age', recorded the new specimen, rendering each feather and fold of skin with

minute brushwork, against a plain background relieved only by (discoloured)

streaks and a conventional row of flowers.

The

same qualities of dispassionate delineation and static, pattern-making

composition informed the now dominant art of portraiture. Jahangir was proud of

his artists' ability to emulate the technique of the English miniatures shown

to him by the ambassador Sir Thomas Roe, and was delighted when Roe was at

first unable to distinguish between an original miniature and several Mughal

copies. The effect on Mughal painting was both refining and somewhat chilling.

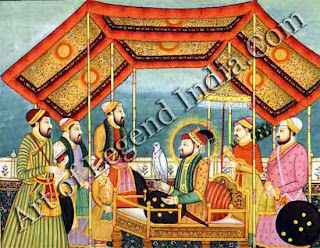

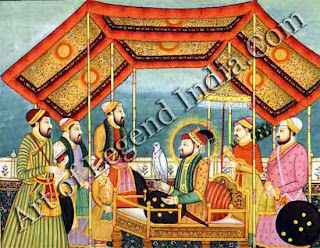

A scene of Jahangir receiving his son Parviz and courtiers in durbar has been

skilfully assembled from individual portrait studies and stock pictorial

elements such as the fountain, the simplified palace architecture, the cypress

and flowering cherry' and the Flemish-inspired landscape.

In this deliberate

compilation there is none of the movement and interaction of figures of Akbar

painting. Each finely portrayed face gazes forward in expressionless isolation an attitude which is, however, appropriate for the solemn formality of the

durbar. The painting can be attributed to Manohar, the son of the great Akbari

artist Basawan, who had developed a vigorous modelling technique and sense of

space from European sources. In deference to Jahangir’s taste, these skills

were modified by his son, who presents the outward show of imperial life,

crystallized in elegant patterns and richly detailed surfaces.

In this deliberate

compilation there is none of the movement and interaction of figures of Akbar

painting. Each finely portrayed face gazes forward in expressionless isolation an attitude which is, however, appropriate for the solemn formality of the

durbar. The painting can be attributed to Manohar, the son of the great Akbari

artist Basawan, who had developed a vigorous modelling technique and sense of

space from European sources. In deference to Jahangir’s taste, these skills

were modified by his son, who presents the outward show of imperial life,

crystallized in elegant patterns and richly detailed surfaces.

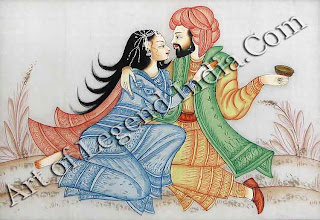

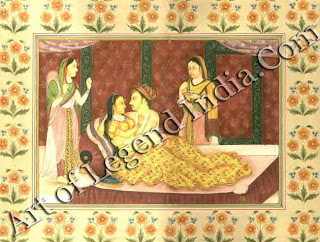

Court

portraiture under Shah Jahan (1627-58), exemplified by the Padshahnama, the

illustrated history of his reign now at Windsor Castle, and became still more

formal and frigid. Each durbar, battle or procession is a grand compilation of

countless individual portraits, painted with a hard, immaculate finish. The

effect is magnificent but heartless and strangely unanimated. Shah jahan's real

passion Was for jewels and architecture: on these he lavished much of the

wealth of the empire, combining them above all in the justly celebrated Taj

Mahal. Album paintings of varied subjects were, however, still produced, such

as a genre scene of an informal musical party by Bichitr, an artist best known

for his accomplished portraiture and cool palette. The painting is in fact an

exercise in the style of Govardhan, another Hindu and one of the most gifted of

all Mughal painters, excelling at keenly observed group portraits of common

people and particularly of holy men as well as kings.

In 1658

Shah Jahn was deposed by his third son, the pious and puritanical Aurangzeb,

and Dara Shikuh, the more free-thinking and artistically inclined heir

apparent, was put to death. During his long reign (1658-1707) Aurangzeb further

dissipated the empire's resources, not like his father by immoderate luxury and

building projects, but by interminable military campaigns in the Deccan. The

court arts languished for want of patronage, and from 168o onwards many

painters took service at provincial courts. A urangzeb was followed in the 18th

century by a succession of effete incompetents who maintained an illusory show

of power while the empire broke up. The sybaritic Muhammad Shah (1719-48), who

when told of some defeat would console himself by contemplating his gardens, was

typical of the age. In 1739 he endured the humiliating sack of Delhi by Nadir

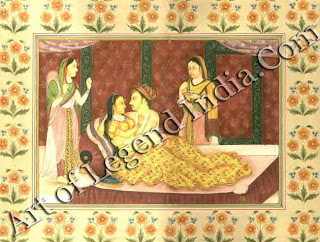

Shah of Persia. A nautch (dancing-party) scene in his zenana shows signs of the

brittle rigidity and vapid sensuality of late Mughal painting, which preserved

much of the technique of the mid-17th century style, but had little

new to say. The emperors after Akbar had insulated themselves within the

increasingly formal and introverted microcosm of court life.

In 1658

Shah Jahn was deposed by his third son, the pious and puritanical Aurangzeb,

and Dara Shikuh, the more free-thinking and artistically inclined heir

apparent, was put to death. During his long reign (1658-1707) Aurangzeb further

dissipated the empire's resources, not like his father by immoderate luxury and

building projects, but by interminable military campaigns in the Deccan. The

court arts languished for want of patronage, and from 168o onwards many

painters took service at provincial courts. A urangzeb was followed in the 18th

century by a succession of effete incompetents who maintained an illusory show

of power while the empire broke up. The sybaritic Muhammad Shah (1719-48), who

when told of some defeat would console himself by contemplating his gardens, was

typical of the age. In 1739 he endured the humiliating sack of Delhi by Nadir

Shah of Persia. A nautch (dancing-party) scene in his zenana shows signs of the

brittle rigidity and vapid sensuality of late Mughal painting, which preserved

much of the technique of the mid-17th century style, but had little

new to say. The emperors after Akbar had insulated themselves within the

increasingly formal and introverted microcosm of court life.

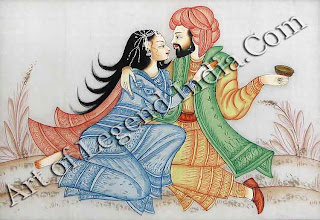

Given inspired

patronage, painting had for a time flourished in this hot-house atmosphere, but

when the empire was played out it too gradually declined into a repetition of

well worn themes, both at Delhi and at the provincial courts of Lucknow and

Murshidabad. After Clive's victory in Bengal in 1757, British power began to

spread across northern India, and by the early 19th century Delhi artists were

emulating the style of painting favoured by the new imperialists. A nautch

party of this period is set in a European mansion with classical columns and

pediments. The figures also arc in the Europeanised 'Company' style, but the

Indian artist has, resourcefully as ever, transformed the alien conventions of

modelling and recession into his own umistakable idiom.

Given inspired

patronage, painting had for a time flourished in this hot-house atmosphere, but

when the empire was played out it too gradually declined into a repetition of

well worn themes, both at Delhi and at the provincial courts of Lucknow and

Murshidabad. After Clive's victory in Bengal in 1757, British power began to

spread across northern India, and by the early 19th century Delhi artists were

emulating the style of painting favoured by the new imperialists. A nautch

party of this period is set in a European mansion with classical columns and

pediments. The figures also arc in the Europeanised 'Company' style, but the

Indian artist has, resourcefully as ever, transformed the alien conventions of

modelling and recession into his own umistakable idiom.

Writer – Andrew Topsfeld

In 1526

Babur, a minor prince from Transoxiana descended from both Tamerlane and

Chingiz Khan, culminated a lifetime of restless wanderings and short-lived

conquests by invading India. He founded a dynasty whose autocratic power and

luxurious display became proverbial as far away as England. Although its

decline was to be lengthy, it endured in name at least until the banishment of

the last Emperor by the British in 1858. For much of this period the cultural

interests and fashions of the imperial court exercised a pervasive influence

throughout the provinces, and not least on the art of painting.

In 1526

Babur, a minor prince from Transoxiana descended from both Tamerlane and

Chingiz Khan, culminated a lifetime of restless wanderings and short-lived

conquests by invading India. He founded a dynasty whose autocratic power and

luxurious display became proverbial as far away as England. Although its

decline was to be lengthy, it endured in name at least until the banishment of

the last Emperor by the British in 1858. For much of this period the cultural

interests and fashions of the imperial court exercised a pervasive influence

throughout the provinces, and not least on the art of painting.  Early in his reign

he set the two Persians to direct a newly recruited studio that grew to some

two hundred native artists. Under his constant supervision the early Mughal

style was thus formed from the fusion of Persian elegance and technique with

the Indian vitality and feeling for natural forms admired by Akbar. The

studio's most grandiose project, taking fifteen years to complete, was a series

of 1400 large illustrations on cloth to the romance of Amir Hamza, a prolix but

action-packed adventure story which was a favourite of the young Akbar.

Accord-ing to one Mughal historian he would himself act as a story-teller,

narrating Hainza's adventures to the inmates of his zenana (harem). In a

typical, the decorative Persian tile patterns and arabesques

stand in contrast to the vigorously painted trees, rocks, gesticulating figures

and gory victims of the leering dragon.

Early in his reign

he set the two Persians to direct a newly recruited studio that grew to some

two hundred native artists. Under his constant supervision the early Mughal

style was thus formed from the fusion of Persian elegance and technique with

the Indian vitality and feeling for natural forms admired by Akbar. The

studio's most grandiose project, taking fifteen years to complete, was a series

of 1400 large illustrations on cloth to the romance of Amir Hamza, a prolix but

action-packed adventure story which was a favourite of the young Akbar.

Accord-ing to one Mughal historian he would himself act as a story-teller,

narrating Hainza's adventures to the inmates of his zenana (harem). In a

typical, the decorative Persian tile patterns and arabesques

stand in contrast to the vigorously painted trees, rocks, gesticulating figures

and gory victims of the leering dragon.  That this realism was to some extent based on a

selective study of European models is shown by an illustration to the

Harivamsa, one of the Hindu mythological texts which Akbar had ordered Badauni

to translate into Persian, to that scholar's pious disgust. Krishna sweeps down

on the bird Garuda to triumph over Indra on his elephant, watched by gods and

celestial beings. The billowing clouds and swirling draperies have Baroque

antecedents, while the coastal landscape with a European boat derives from

Flemish art. Abu'l Fazl, besides echoing his master's praise of Hindu artists,

whose 'pictures surpass our conception of things', refers also to 'the

wonderful works of the European painters, who have attained world-wide fame'.

He more-over tells us of an album prepared for Akbar which contained portraits

of himself and his courtiers. This was the first time in Indian art that

portraiture of the Western type, treating its subject as an individual

character rather than as a socially or poetically determined type, had been so

systematically pursued.

That this realism was to some extent based on a

selective study of European models is shown by an illustration to the

Harivamsa, one of the Hindu mythological texts which Akbar had ordered Badauni

to translate into Persian, to that scholar's pious disgust. Krishna sweeps down

on the bird Garuda to triumph over Indra on his elephant, watched by gods and

celestial beings. The billowing clouds and swirling draperies have Baroque

antecedents, while the coastal landscape with a European boat derives from

Flemish art. Abu'l Fazl, besides echoing his master's praise of Hindu artists,

whose 'pictures surpass our conception of things', refers also to 'the

wonderful works of the European painters, who have attained world-wide fame'.

He more-over tells us of an album prepared for Akbar which contained portraits

of himself and his courtiers. This was the first time in Indian art that

portraiture of the Western type, treating its subject as an individual

character rather than as a socially or poetically determined type, had been so

systematically pursued.  He was also passionately curious about the forms and behavior

of plants and animals, and it has been remarked that he might have been a

better and happier man as the head of a natural history museum. When in 1612 a

turkey cock was brought in a consignment of rarities purchased from the

Portuguese in Goa, Jahangir as usual wrote up his observations, being

particularly fascinated by its head and neck: 'like a chameleon it constantly

changes colour'. His flower and animal artist, Mansur, known as 'Wonder of the

Age', recorded the new specimen, rendering each feather and fold of skin with

minute brushwork, against a plain background relieved only by (discoloured)

streaks and a conventional row of flowers.

He was also passionately curious about the forms and behavior

of plants and animals, and it has been remarked that he might have been a

better and happier man as the head of a natural history museum. When in 1612 a

turkey cock was brought in a consignment of rarities purchased from the

Portuguese in Goa, Jahangir as usual wrote up his observations, being

particularly fascinated by its head and neck: 'like a chameleon it constantly

changes colour'. His flower and animal artist, Mansur, known as 'Wonder of the

Age', recorded the new specimen, rendering each feather and fold of skin with

minute brushwork, against a plain background relieved only by (discoloured)

streaks and a conventional row of flowers.  In this deliberate

compilation there is none of the movement and interaction of figures of Akbar

painting. Each finely portrayed face gazes forward in expressionless isolation an attitude which is, however, appropriate for the solemn formality of the

durbar. The painting can be attributed to Manohar, the son of the great Akbari

artist Basawan, who had developed a vigorous modelling technique and sense of

space from European sources. In deference to Jahangir’s taste, these skills

were modified by his son, who presents the outward show of imperial life,

crystallized in elegant patterns and richly detailed surfaces.

In this deliberate

compilation there is none of the movement and interaction of figures of Akbar

painting. Each finely portrayed face gazes forward in expressionless isolation an attitude which is, however, appropriate for the solemn formality of the

durbar. The painting can be attributed to Manohar, the son of the great Akbari

artist Basawan, who had developed a vigorous modelling technique and sense of

space from European sources. In deference to Jahangir’s taste, these skills

were modified by his son, who presents the outward show of imperial life,

crystallized in elegant patterns and richly detailed surfaces.  In 1658

Shah Jahn was deposed by his third son, the pious and puritanical Aurangzeb,

and Dara Shikuh, the more free-thinking and artistically inclined heir

apparent, was put to death. During his long reign (1658-1707) Aurangzeb further

dissipated the empire's resources, not like his father by immoderate luxury and

building projects, but by interminable military campaigns in the Deccan. The

court arts languished for want of patronage, and from 168o onwards many

painters took service at provincial courts. A urangzeb was followed in the 18th

century by a succession of effete incompetents who maintained an illusory show

of power while the empire broke up. The sybaritic Muhammad Shah (1719-48), who

when told of some defeat would console himself by contemplating his gardens, was

typical of the age. In 1739 he endured the humiliating sack of Delhi by Nadir

Shah of Persia. A nautch (dancing-party) scene in his zenana shows signs of the

brittle rigidity and vapid sensuality of late Mughal painting, which preserved

much of the technique of the mid-17th century style, but had little

new to say. The emperors after Akbar had insulated themselves within the

increasingly formal and introverted microcosm of court life.

In 1658

Shah Jahn was deposed by his third son, the pious and puritanical Aurangzeb,

and Dara Shikuh, the more free-thinking and artistically inclined heir

apparent, was put to death. During his long reign (1658-1707) Aurangzeb further

dissipated the empire's resources, not like his father by immoderate luxury and

building projects, but by interminable military campaigns in the Deccan. The

court arts languished for want of patronage, and from 168o onwards many

painters took service at provincial courts. A urangzeb was followed in the 18th

century by a succession of effete incompetents who maintained an illusory show

of power while the empire broke up. The sybaritic Muhammad Shah (1719-48), who

when told of some defeat would console himself by contemplating his gardens, was

typical of the age. In 1739 he endured the humiliating sack of Delhi by Nadir

Shah of Persia. A nautch (dancing-party) scene in his zenana shows signs of the

brittle rigidity and vapid sensuality of late Mughal painting, which preserved

much of the technique of the mid-17th century style, but had little

new to say. The emperors after Akbar had insulated themselves within the

increasingly formal and introverted microcosm of court life.  Given inspired

patronage, painting had for a time flourished in this hot-house atmosphere, but

when the empire was played out it too gradually declined into a repetition of

well worn themes, both at Delhi and at the provincial courts of Lucknow and

Murshidabad. After Clive's victory in Bengal in 1757, British power began to

spread across northern India, and by the early 19th century Delhi artists were

emulating the style of painting favoured by the new imperialists. A nautch

party of this period is set in a European mansion with classical columns and

pediments. The figures also arc in the Europeanised 'Company' style, but the

Indian artist has, resourcefully as ever, transformed the alien conventions of

modelling and recession into his own umistakable idiom.

Given inspired

patronage, painting had for a time flourished in this hot-house atmosphere, but

when the empire was played out it too gradually declined into a repetition of

well worn themes, both at Delhi and at the provincial courts of Lucknow and

Murshidabad. After Clive's victory in Bengal in 1757, British power began to

spread across northern India, and by the early 19th century Delhi artists were

emulating the style of painting favoured by the new imperialists. A nautch

party of this period is set in a European mansion with classical columns and

pediments. The figures also arc in the Europeanised 'Company' style, but the

Indian artist has, resourcefully as ever, transformed the alien conventions of

modelling and recession into his own umistakable idiom.

0 Response to "The Mughal School Painting"

Post a Comment