The

Vakatakas succeeded the Satavahanas in the Deccan. They were powerful rulers

and had matrimonial alliances with the Bharasivas and the Guptas. The Vakatakas

are first mentioned in inscriptions of the second century A.D. from Amaravati.

They thus appear to have migrated from the Krishna valley and established a

kingdom that grew slowly in the later centuries. The Vakataka ruler Pravarasena

appears to have been not only highly literary but also a patron of art and

beauty in all its forms. Some of the caves at Ajanta have inscriptions of the

Vakataka period and can be definitely dated and attributed to the time of these

rulers.

The

Vakatakas succeeded the Satavahanas in the Deccan. They were powerful rulers

and had matrimonial alliances with the Bharasivas and the Guptas. The Vakatakas

are first mentioned in inscriptions of the second century A.D. from Amaravati.

They thus appear to have migrated from the Krishna valley and established a

kingdom that grew slowly in the later centuries. The Vakataka ruler Pravarasena

appears to have been not only highly literary but also a patron of art and

beauty in all its forms. Some of the caves at Ajanta have inscriptions of the

Vakataka period and can be definitely dated and attributed to the time of these

rulers.

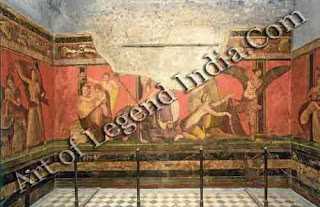

While

the early caves show the earlier features of architecture of the Satavahana

period, with typical pillars, facade decoration with railing and chaitya window

pattern, etc., and with the uddesika stupa, devoid of any human representation

of Buddha, when such anthropomorphic representation was considered

disrespectful to the Master, the later caves have the more elaborate pillars

and capitals of the Gupta-Vakataka period, the more developed chaitya window

type and sculptural embellishment, with the uddesika stupa in the chailya,

clearly showing the Master in human form on the sides.

The

sculptures at Ajanta, especially in the later caves, show the high watermark of

perfection during the age of the Vakatakas. There can be no better examples

than these for a study of Vakataka art in the Deccan, coeval with Gupta art in

the north. The paintings completely cover the walls, pillars and ceilings at

Ajanta. They constitute a great gallery of Buddhist art illustrating scenes

from the life of the Master, his previous lives comprising the jatakas and

avadanas and floral and animal motifs. These last are cleverly woven into

diverse designs of great originality.

From an

inscription in Cave 16, it is learnt that it was dedicated to the monks by

Varahadeva, the minister of the Vakataka king Harishena, in the latter half of

the fifth century A.D. In Cave 26 there is another inscription which records

the gift of the temple of Sugata by the monk Biddhabhadra, a friend of

Bhaviraja, the minister of the king of Asmaka. Its date, paleographically,

seems to be the same. A contemporary fragmentary inscription records the gift

of the hall by Upendra in Cave 20. These inscriptions are all in the box-headed

letters of the Vakatakas and help us to understand their date. The art here is

thus of the Vakatakas, just as the earlier phase illustrates Satavahana art.

The

mode of painting at Ajanta is the tempera and the materials used are very

simple. The five colours usually described in all the silpa texts are found

here red ochre, yellow ochre, lamp black, lapis lazuli and white. The first

coating on the surface of the rock was of clay mixed with rice husk and gum. A

coat of lime was applied over this, carefully smoothed and polished. On this

ground the paintings were created. The outline drawing was in dark brown or

black and subsequently colours were added. Effects of light and shade were

achieved by the process of streaks and dots illustrating the methods of pat

ravartana, stippling and hatching mentioned in the silpa texts. The lines

composing the figures painted at Ajanta are sure, sinuous, rich in form and

depth and recall the lines in praise of the effective line drawing in the

Viddhasalabhanfika, api, laghu hkhiteyam drisyate purnamurtih, where by a few

lines sketched, the maximum effect of form is produced. The masters at Ajanta

have thus demonstrated the superiority of line drawing as given in the

Vishudharrnottara, rekham prasamsantyacharyah, the masters praise effective

line drawing as the highest in art.

The

painter at Ajanta has studied life around him and natural scenes of great

beauty with intense sympathy and appreciation. Plant and animal life has

interested him considerably. He has lovingly treated such themes of flora and

fauna as he has chosen to depict. The elephants under the banyan tree in Cave 10,

the geese in the Hamsa Jataka from Cave 17, the dear in the Miga Jataka, also

from the same cave, may be cited as a few examples of the tender approach of

the painter to the themes of animals and birds. He has been equally at home in

ably representing the dazzling magnificence of the royal court, the simplicity

of rural life and the hermit's tranquil life amidst sylvan surroundings. The

Vessantara Jataka illustrates the prince as the very picture of magnificence,

as also the simplicity of the hermit and the poor Brahmin as an inexorable

beggar.

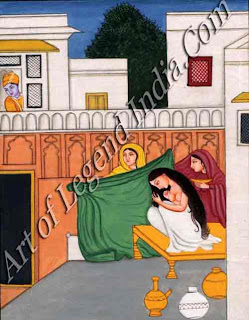

The scene in Cave 27 of prince Vessantara, with his consort, driving on

the main road, depicting different merchants in pursuit of their trade, is a

beautiful picture of economic life in ancient India. The landing in Ceylon is a

splendid representation of royal glory in Cave 17. The interior of the palace

giving a glimpse of the king and the queen in the harem or in the garden

reveals that nothing was hidden from the gaze of the court painter. He could

portray the charm of a close embrace, the arm entwining the neck in

kanthaslesha or the sidelong glances of a loving damsel. The toilet of the

princess is another example of a similar theme. Th imagination of the painter

in portraying the celestials has probably no better examples to proclaim its

eminence as the divine musicians floating in the air from Cave 17.

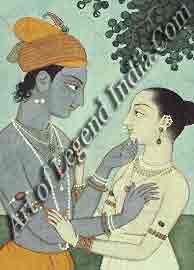

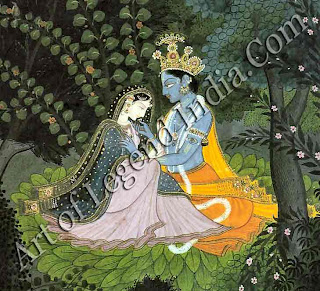

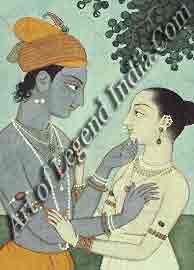

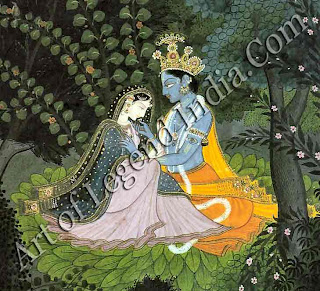

The gay

theme of dampati, or loving couples, has excellent examples at Ajanta. Of this

a whole row is above the entrance doorway of Cave 17. The versatility of the

Vakataka painter in creating diverse poses is here evident in the several

seated dampatis. The artists could so elevate themselves mentally as to be able

to depict magnificently such noble themes as Maraciharshana in Cave 1, Buddha's

descent from heaven at Sankisa in Cave 17, and prince Siddhartha and Yasodhara

in Cave 1, all magnificent representations of the Master in different

attitudes. The long panels and borders from the ceilings of swans and birds,

Vidyadhara couples, auspicious conches and lotuses as well as sinuous rhizomes

and stalks, with lotuses in bud and bloom, and leaves covering large areas

reveal the capacity of the artist to create diverse patterns of great artistic

value.

The gay

theme of dampati, or loving couples, has excellent examples at Ajanta. Of this

a whole row is above the entrance doorway of Cave 17. The versatility of the

Vakataka painter in creating diverse poses is here evident in the several

seated dampatis. The artists could so elevate themselves mentally as to be able

to depict magnificently such noble themes as Maraciharshana in Cave 1, Buddha's

descent from heaven at Sankisa in Cave 17, and prince Siddhartha and Yasodhara

in Cave 1, all magnificent representations of the Master in different

attitudes. The long panels and borders from the ceilings of swans and birds,

Vidyadhara couples, auspicious conches and lotuses as well as sinuous rhizomes

and stalks, with lotuses in bud and bloom, and leaves covering large areas

reveal the capacity of the artist to create diverse patterns of great artistic

value.

The

Vakataka traditions as seen at Ajanta are derived from the earlier Satavahana.

This can be clearly seen in several echoes of the painted figures here from

those of Amaravati. It is mainly the decorative element, chiefly composed of

pearls and ribbons, so characteristic of the Gupta-Vakataka age that

distinguishes them from the simpler but nobler art of the Satavahanas.

The

Vakataka traditions continued in later sculpture. This can be seen in figures

in identical poses found at Mahabalipuram inspired by those at Ajanta which

them-selves in turn recall the earlier ones from Amaravati. The identical twist

of the right leg put forward in exactly the same pose as at Ajanta and at

Mahabalipuram cannot be a chance coincidence. The beautiful paintings in colour

at Ajanta help us to conjecture and fully comprehend the glory of earlier

Amaravati sculpture and the culture it represents. At Amaravati, the lack of

colour precludes the comprehension of the rich jewellery, colourful gems, gay

and glamorous drapery, rich furniture, imposing architecture and pageantry in

the absence of colour.

There

are excellent illustrations in these paintings at Ajanta of the six limbs of

painting, shadanga, composed of rupabheda, variety of form, pramana, proper

proportion, bhava, depiction of emotion, lavanya yojana, infusion of grace,

sadrisya, likeness and varnikabhanga, mixing of colours to produce an effect of

modelling. The diversity of form at Ajanta is indeed incredible. The painters

here mastered the vast complex of human, animal and plant form in addition to

giving free scope to their imagination and were creating designs galore. The

master at Ajanta has control over not only the proportions of individual

figures but also has the ability to group them and he has designed excellent compositions.

Emotion is at its best in the narration of scenes from the legends; the grace

in some of the figures bespeaks lavanyayojana. While figures are repeated as

the Vessantara Jataka, the element of portraiture is clearly made manifest and

sadrisya is very obvious. The painter's colour technique easily helps us to pay

him a tribute for his capacity in varnikabhanga.

As a

narrator of the legends, the painter as well as the sculptor at Ajanta has

deviated from the normal course as in other monuments occasionally, but always

the effect has been greater.

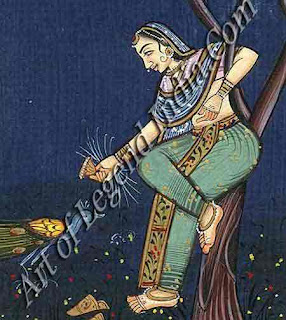

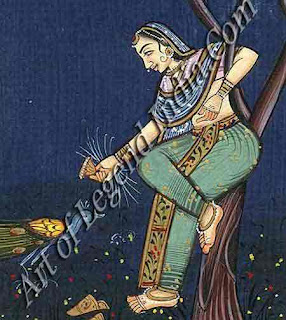

Irandati

is shown on a swing in the Vibhurapandita lataka at Ajanta. This enhances the

charm of the Naga princess, the desire to marry whom made the Yaksha Punnaka

play the game of dice, win, and bring the wise Vidhurapandita to the palace of

the Naga queen. It is thus here more beautiful than even at Bharhut or

Amaravati or Borobudur.

The

version of the Chhaddanta Jataka at Ajanta heightens the pathos by the noble

act of the elephant who not only offered his tusks to the wicked hunter but

also helped him even in pulling them out. But this is from the early Satavahana

series in Cave 10 and probably the Vakataka painter followed this earlier

tradition deviating from the normal representation for producing greater

effect.

The

Hatnsa Jataka is probably more vivid at Ajanta in painting than even at

Amaravati in sculpture.

But the

detailed and touching story of the Sarna Jataka is probably nowhere better

presented than here in the paintings at Ajanta. There is an elaboration here of

the Vessantara Jataka which makes it probably the best narrative of this story

excelling even that at Goli or at Sanchi.

The

story of Mahakapi Jataka or Sarabhamiga Jataka is different from the stories

usually chosen and depicted in other monuments. The Matiposaka Jataka is again

elaborated here and is different from the simple single scene at Goli.

The

Mahisha Jataka, represented at Borobudur, is a rare one in India and is found

here. The Valahassa Jataka which is represented on a Kushana rail pillar is

better elaborated at Ajanta following the Divyavadana story.

The

Sibi Jataka at Ajanta presents a different version from the one of Kshemendra in

the Avandana kalpalata, the source of which has inspired the scenes at

Amaravati, Nagarjunakonda and other places.

Even in

the scenes from Buddha's life, the master at Ajanta has excelled. The story of

Nalagiri is probably more effectively presented at Ajanta than even at

Amaravati Goli. The same is the case with the presentation of Rahula to Buddha

which is a greater masterpiece at Ajanta than the one at Amaravati though

probably the medallion in the British Museum can stand comparison with any

depiction of this scene from any Buddhist monument in the world.

The

descent of Buddha from heaven and the elaborate Maradharshana scene are

unrivalled and probably form the greatest attraction in the scenes from

Buddha's life from the Ajanta caves.

Cave 1

contains great masterpieces illustrating scenes from Buddha's life. A large

panel shows prince Siddhartha and Yasodhara, another Bodhisattva Vajrapani,

Maradharshana, the miracle of Sravasti and the story of Nanda.

The

Master, seated under the Bodhi tree in the Maradharshana episode, is shown

determined to be the enlightened one, unaffected by the temptation of Mara and

his beautiful daughters, and unruffled though attacked and frightened by the

mighty hosts of his opponents.

In the

miracle of Sravasti, Buddha is shown simultaneously in innumerable forms before

a large gathering headed by king Prasenajit. This was to confuse the heretics.

The

story of Nanda gives how, converted, unwillingly, by Buddha, Nanda still longed

for his tear-eyed beautiful wife, Sundari, who pined for him in her palace. The

painting here gives a side picture of Sundari in grief. The jatakas in this

cave include Sibi jataka, Samkhapala fataka, Mahajanaka Jataka and Champeyya

fataka.

The

first narrates how the Boddhisattva offered his own flesh to a hawk to protect

a pigeon that it was after. The Samkhapala Jataka is the story of a Naga prince

who patiently allowed himself to be worried by a troop of wicked men and

rescued by a merciful passerby, gratefully took the latter and entertained him

in his magnificent underground abode. The painting depicts both the happy

situation of the Naga king and his gratitude to his benefactor.

The

Mahajanaka fat aka depicts the story of Mahajanaka who married the princess

Sivali and, in spite of her at-tempts to retain him in worldly pleasures, made

up his mind to be an ascetic, resulting in Sivali following her husband's path.

The

Champeyya Jataka is the story of the Bodhisattva, born as a Naga prince,

Champeyya, who allowed himself to be caught by a snake-charmer and was rescued

by his queen Sumana, by requesting the king of Banaras to inter-cede on her

behalf.

Cave 2

contains a large-size painting of Bodhisattva, the dream of Maya and its

interpretation, the descent from heaven, the birth and the seven steps. The

jatakas depicted here are Hatnsa Jataka, Vidhurapandita jataka, Runt Jataka and

Puma Avadana. There are fragments of painted inscriptions mentioning the

donation of a thousand painted Buddhas as also some verses from the Kshanti

jataka from the jatakantala.

The

Hamsa jataka relates the story of the queen, Khema, who dreamt of a golden

goose preaching the law. She prevailed on her husband the king to get the

golden goose and his companion to be caught by a fowler and brought to her to

give her a discourse on the law. The painting shows the golden goose enthroned and

admonishing the queen. Earlier the capture of the bird by the fowler is shown.

The lotus-lake, the abode of the golden goose, is picturesquely portrayed.

The

Vidhurapandita jataka is the story of the Naga, queen, who desired to listen to

the learned discourse of Vidhurapandita, the wise minister of the king

Indraprastha. According to the story, the beautiful Naga princess Irandati was

promised in marriage to whomsoever brought the heart of Vidhurapandita. The

Yaksha Punnaka won Vidhurapandita as a stake, by defeating his royal master in

a game of dice, brought him to the Naga queen, and thus won the hand of the

Naga princess. The story is elaborately shown here presenting the beautiful

princess Irandati on a swing, the game of dice, Vidhurapandita's discourse in

the Naga palace and the happy union of Punnaka and Irandati.

The

Runt Jataka is the story from the Divyavadana of the conversion of Puma by

Buddha and the miraculous rescue of his brother, Bhavila.

The

Kshanti Jataka is the story of a prince who was patience incarnate and put up

with all the persecution he was subjected to by the King of Banaras.

Cave 16

is one of the most beautiful viharas of Ajanta. The inscription in this cave

mentions it as dedicated by Varahadeva, the minister of the Vakataka king,

Harishena, towards the end of the fifth century A.D. The picture given of this

dwelling in this inscription that it was adorned with windows, doors, beautiful

picture-galleries (vithis), carvings of celestial nymphs, ornamental pillars

and stairs and a shrine chaityamandira, and a large reservoir and shrine of the

lord of the Nagas is all borne out quite correctly.

The

paintings here represent the story of Nanda, the miracle of Sravasti, Sujata's

offering, the incident of Trapusha and Bhallika, the incident of the ploughing

festival, the visit of Asita, the prince at school and the dream of Maya.

The

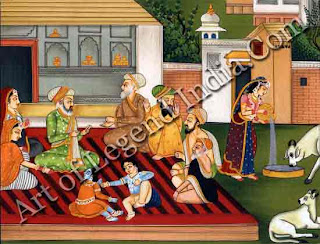

story of Nanda relates to his conversion. When he returned to Kapilavastu,

Buddha visited Nanda's mansion. He was then helping his beautiful wife Sundari

at her toilet. Nanda rose to greet the Master, but Buddha gave him his begging

bowl and bade him to follow him to the monastery. Here he was converted against

his will. However, to make Nanda steadfast in his vows as a monk, Buddha showed

him the most lovely nymphs in heaven, where he conducted him. These he promised

him if he was true to monkhood. Nanda soon became a devoted monk, and realising

the truth of religious life, no more thought of the heavenly damsels. The

scenes here depict Nanda's conversion and his journey to heaven with Buddha to

see the celestial nymphs. This is comparable to the sculptural presentation of

the same theme at Nagarjunakonda. Among the jatakas painted in this cave are

the Hasti Jataka, Mahaummagga Jataka and Sutasoma fat aka.

The

Hasti Jataka from the Jatakamala is the story of a noble elephant who killed

himself by falling from a great height to feed a number of hungry travellers.

The Mahaummagga Jataka is a very lengthy one from which an episode is chosen

here for depiction. It is the riddle of the 'son'. Mahosada acted as a judge to

settle a dispute between an ogress and the real mother of the child as both

claimed the little one as their own. Mahosada asked them both to pull the

child. He discovered the real mother in the one who readily gave in when she

could not bear to see the child experiencing such severe pain on that account.

Other riddles like that of the 'chariot' and of the 'cotton thread' from the

same story are narrated further on.

The

Sutasoma Jataka, also from the Jatakamala, narrates how a lioness was

infatuated with a charming prince Sudasa who came hunting to the forest. She

licked the feet of the sleeping prince and conceived a child. When born, this

freak became a cannibal prince, but was finally converted into prince Sutasoma.

The painting shows the lioness licking the feet of the somnolent prince.

As

given in an inscription incised on the wall of the verandah, Cave 17 was

excavated by a feudatory of the Vakataka king, Harishena. It has an elaborately

carved doorway, with a fine floral design. The carvings of Ganga and Yamuna on

the door-jambs are most pleasing.

Noteworthy

among the paintings here are the seven earlier Buddhas, Vipasyi, Sikhi,

Visvabhu, Krakuchchanda, Kanakamuni, Kasyapa and Sakyamuni as well as Maitreya,

the Buddha. to come, the subjugation of Nalagiri, the descent at Sankisa, the

miracle of Sravasti and the meeting of Rahula.

The

jatakas represented here are the Chhaddanta jataka, Mahakapi Jataka I, Hasti

jataka, Hamsa Jataka, Vessantara jataka, Mahakapi jataka II, Sutasoma jataka,

Sarabhamiga Jataka, Machchha Jataka, Matiposaka Jataka, Sama jataka, Mahisha

Jataka and the story of Simhala from Divyavadana with details from Valahassa

jataka, Sibi jataka, Ruru jataka, and Nigrodamiga jataka.

The

Mahakapi jataka I narrates the story of the Bodhisattva, who was born as the

leader of a troop of monkeys. Once, while tasting sweet mangoes on the banks of

the river, the monkeys were suddenly attacked by the archers of Brahmadatta of

Banaras. To save the animals, the Bodhisattva hurriedly stretched out a bamboo

to form a bridge to help them cross over. Finding it, however, slightly short,

he stretched his own body to complete the bridge. The king was touched by the

noble spirit of the animal, honoured him greatly and listened to his discourse

on dharina. The river, the orchard of trees laden with mangoes, the strange

bridge and the sermon of the monkey are all painted.

The

Vessantara jataka has for its theme the life of the noble prince who never

stinted gifting anything begged of him. In fact, he gave away even the precious

elephant, responsible for the prosperity of his realm, which caused him

banishment from his own kingdom along with his wife and children. Finally, he

gave away all that he had, including his chariot and horses and even his

children and wife. The panels here show the banishment, Vessantara leaving the

city in his chariot, his wife in the forest, his gift of his children to wicked

Brahman Jujaka, the restoration of the children to their grandfather and the

happy return of the prince and the princess.

The

Mahakapi Jataka II recounts the tale of the monkey who rescued an ungrateful

man from a deep pit. In spite of the latter's attempt to kill him, the monkey

with a most magnanimous spirit, showed him the way out of the forest. The

scenes depict the animal helping the man out of the pit and the ingratitude of

the latter.

The

Sarabhamiga Jataka gives the story of the king of Banaras helped out of a pit

by a stag.

The

Machchha Jataka narrates the legend of the Bodhisattva, who saved his kin from

death by drought by making a solemn asseveration to bring down rain.

The

Matiposhaka Jataka gives the story of the filial affection of the elephant who

took care of his blind mother. Captured by the king of Banaras, he refused to

touch food till the king, out of compassion, got him to return to his blind

parent. The scenes painted depict the refusal of the elephant to touch food,

his release and happy reunion with his mother.

The

Mahisha Jataka is the story of the Bodhisattva, who patiently put up with the

antics of a monkey.

The

Simhala Avadana narrates the story of Simhala, who accompanied by several

merchants, was shipwrecked on a strange island of demonesses, who in the guise

of beautiful nymphs, lured those unfortunately stranded there and gobbled them

up. The Bodhisattva, born as a horse, offered to rescue the shipwrecked

merchants, but those who stayed behind were destroyed by the ogresses. One of

the latter followed Simhala in the guise of a beautiful woman, with a child in

her arms, and claimed his as her husband before the king, who, struck by her

beauty, made her his queen despite the advice of his ministers. This resulted

in the gradual annihilation of the palace folk that were devoured by the

demonesses. Simhala drove them out, set out with an army to reach their island,

defeated them and became the ruler there.

The

Sibi Jataka gives the story of a king who gladly gave away his eyes to a blind

Brahman at his request, little knowing that it was Sakra himself in disguise.

The panel has a short inscription Sibiraja painted in Vakataka letters.

The

Ruru Jataka gives the story of the capture of the deer to preach the law to the

king.

The

Nigrodhamiga Jataka is the story of the Bodhisattva born as a compassionate

deer, who offered himself to be killed in place of a pregnant doe to feed the

king of Banaras. The ruler was so touched by this act of kindness that he

adored the animal and listened to his sermon on karuna.

Cave 19

has panels representing Buddha with his begging-bowl before his son Rahula and

Yasodhara.

The

Vakatakas succeeded the Satavahanas in the Deccan. They were powerful rulers

and had matrimonial alliances with the Bharasivas and the Guptas. The Vakatakas

are first mentioned in inscriptions of the second century A.D. from Amaravati.

They thus appear to have migrated from the Krishna valley and established a

kingdom that grew slowly in the later centuries. The Vakataka ruler Pravarasena

appears to have been not only highly literary but also a patron of art and

beauty in all its forms. Some of the caves at Ajanta have inscriptions of the

Vakataka period and can be definitely dated and attributed to the time of these

rulers.

The

Vakatakas succeeded the Satavahanas in the Deccan. They were powerful rulers

and had matrimonial alliances with the Bharasivas and the Guptas. The Vakatakas

are first mentioned in inscriptions of the second century A.D. from Amaravati.

They thus appear to have migrated from the Krishna valley and established a

kingdom that grew slowly in the later centuries. The Vakataka ruler Pravarasena

appears to have been not only highly literary but also a patron of art and

beauty in all its forms. Some of the caves at Ajanta have inscriptions of the

Vakataka period and can be definitely dated and attributed to the time of these

rulers.

The gay

theme of dampati, or loving couples, has excellent examples at Ajanta. Of this

a whole row is above the entrance doorway of Cave 17. The versatility of the

Vakataka painter in creating diverse poses is here evident in the several

seated dampatis. The artists could so elevate themselves mentally as to be able

to depict magnificently such noble themes as Maraciharshana in Cave 1, Buddha's

descent from heaven at Sankisa in Cave 17, and prince Siddhartha and Yasodhara

in Cave 1, all magnificent representations of the Master in different

attitudes. The long panels and borders from the ceilings of swans and birds,

Vidyadhara couples, auspicious conches and lotuses as well as sinuous rhizomes

and stalks, with lotuses in bud and bloom, and leaves covering large areas

reveal the capacity of the artist to create diverse patterns of great artistic

value.

The gay

theme of dampati, or loving couples, has excellent examples at Ajanta. Of this

a whole row is above the entrance doorway of Cave 17. The versatility of the

Vakataka painter in creating diverse poses is here evident in the several

seated dampatis. The artists could so elevate themselves mentally as to be able

to depict magnificently such noble themes as Maraciharshana in Cave 1, Buddha's

descent from heaven at Sankisa in Cave 17, and prince Siddhartha and Yasodhara

in Cave 1, all magnificent representations of the Master in different

attitudes. The long panels and borders from the ceilings of swans and birds,

Vidyadhara couples, auspicious conches and lotuses as well as sinuous rhizomes

and stalks, with lotuses in bud and bloom, and leaves covering large areas

reveal the capacity of the artist to create diverse patterns of great artistic

value.

0 Response to "Introduction to Vakataka "

Post a Comment