Because

of its unique geographical, historical and cultural background, Rajas-than has

earned much fame. On one hand, there are the high peaks of the Aravalli Hills,

valleys with green vegetation and the beauty of nature, while on the other hand

are large expanses of desert.

In the

annals of Indian history, this territory had ever belonged to brave men and

dedicated women. Different tribes, their way of living, style of dress, and

cultural charm are unique and colourful. In one direction are the impregnable

forts of Ranthambor, Chittor and Jaisalmer, while in another are the ancient

and artistic temples of Dilwara, Ranakpur, Mandore, Paranagar and Badoli.

In a

third direction tall palaces and other buildings, symbols of feudal glory,

exist. In still another are huts built according to folk art style and

belonging to Bhil tribes, Meenas and Girasias. Public figures decked out in

colourful costumes are another highlight of this state. Architecture,

iconography, music, literature and paintings of this region possess significant

characteristics. Rajasthan is undoubtedly a glorious land of artists.

In the

domain of world painting India occupies a unique and honourable place. Buddhist

and Jain art in the styles of Pal, Gujarat, Apbhransh-Rajasthani, Mughal and

Pahari have ever kept intact the traditions of Indian painting since the 2nd

century A.D. till the present day. In this series of paintings Rajasthani art,

adopting the traditions of Ajanta has developed its own unique cultural

perspective and history.

Nomenclature

With

regard to the nomenclature of Rajasthani painting, scholars hold varied

opinion. Some call it Rajput painting and others Rajasthani painting. Ananda

Coomaraswamy was the first scholar who scientifically classified Rajasthani

painting in his book titled Rajput Painting in 1916.

With

regard to the nomenclature of Rajasthani painting, scholars hold varied

opinion. Some call it Rajput painting and others Rajasthani painting. Ananda

Coomaraswamy was the first scholar who scientifically classified Rajasthani

painting in his book titled Rajput Painting in 1916.

According

to him, the theme of Rajput painting relates to Rajputana and the hill states

of Punjab. He divided it into two parts, Rajasthani concerning Rajputana and

Pahari relating to the hill states of Jammu, Kangra, Garhwal, Basohli, Chamba.

The administrators of these states, often belonging to the Rajput clan, had

termed these paintings Rajput.

According

to Coomaraswamy, Rajasthani painting spread widely from Bikaner to the border

of Gujarat and from Jodhpur to Gwalior and Ujjain. Amber, Aurachha, Udaipur,

Bikaner and Ujjain had earned the reputation of being centres of artistic

activities. But contrary to this view, Raikrishan Dass opines:

Dr

Swami had classified traditional Indian painting in two parts, the Rajput and

Mughal styles, but there is no substance in identifying it as Rajput style.

Even though the Rajputs were a ruling class, the cumulative effect of such a

clan could not influence the style of art which had different centres in the

whole country.

Basil

Grey comments: "Rajputana has been a centre of diverse princely indigenous

states, but the expansion of Rajasthani painting had taken place from

Bundelkhand to Gujarat and states ruled by Pahari Rajputs, that is why the name

Rajput painting seems plausible."' Vachaspati Garrola had recognised only

Rajasthani painting under the auspices of the Rajput style of painting, which

seems to be more ambiguous.

According

to these arguments, all paintings of the Rajasthani school could be placed

under the Rajput style. The region termed Rajputana under British rule has

after independence been named Rajasthan with little variation. Before the

advent of the British this whole state could have been known by a single name,

but no substantial evidence could be produced to uphold this view. Only Col Tod

named this region Rayathan or Rajasthan. But British officers often used to

call it Rajputana. Hence we treat Rajasthani painting as that style which is an

eternal heritage of this state. Many connoisseurs of art who had given this

style various names like Raikrishan Dass, Ram Gopal Vijayavargia, Karl

Khandalawala, Dr Moti Chandra, Kr. Sangram Singh and Ananda Coomaraswamy

deserve special mention here.

According

to these arguments, all paintings of the Rajasthani school could be placed

under the Rajput style. The region termed Rajputana under British rule has

after independence been named Rajasthan with little variation. Before the

advent of the British this whole state could have been known by a single name,

but no substantial evidence could be produced to uphold this view. Only Col Tod

named this region Rayathan or Rajasthan. But British officers often used to

call it Rajputana. Hence we treat Rajasthani painting as that style which is an

eternal heritage of this state. Many connoisseurs of art who had given this

style various names like Raikrishan Dass, Ram Gopal Vijayavargia, Karl

Khandalawala, Dr Moti Chandra, Kr. Sangram Singh and Ananda Coomaraswamy

deserve special mention here.

Origin and Development

Details

regarding the place of birth of Rajasthani painting, and the time and history

of circumstances concerning its development, are not yet known. By having

compiled books pertaining to many styles of Rajasthani painting different

scholars have unfolded the history of the 17th century and its aftermath,

but their earlier history is riven with contradictions. Art expert Herman Goetz

observes: "Hardly a year or half passes but new findings about Rajasthani

painting thoroughly alter our old conceptions. Particularly, the latest

knowledge about Mewar paintings has raised many question marks."

On the

basis of earlier views Western scholars had recognised that the Rajasthani

style flourished in various princely states after the downfall of the Mughal

Empire. Some scholars however hold the view that it was merely an offshoot of

Mughal painting, and prospered in the reign of Jehangir. On the strength of new

researches undertaken and opinions formed years ago these views have been

dismissed.

Hence

these views, also expressed by Dr Coomaraswamy, do not appear appropriate even

though historically they are highly significant!' With reference to the

parameters regarding the antiquity of Rajasthani paintings, Dr Goetz presented

his research papers, which throw light on its history.' Karl Khandalawala

discussed in detail the origin and development of this painting.

Great

scholars like Raikrishan Dass, Pramod Chandra, Sangram Singh, Satya Prakash,

Anand Krishan, Hiren Mukherji and others also published scholarly articles from

time to time which highlight details of the origin and growth of Rajasthani

painting. On the basis of this research and many available ancient paintings it

is now generally admitted that Rajasthani painting is a significant link with

traditional Indian painting.

Tibetan

historian Tara Nath (16th century) refers to an artist named Shri

Rangdhar who lived in Maru Pradesh (Marwar) in the 7th century but

paintings of this period are not available. The period from the 6th century

to the 12th century was a great landmark in the history of Rajasthan. From the

8th to the 10th centuries this province was termed Gurjaratra, hence

with the development of art and other vocations painting might have flourished

here. Among available compilations, pictorial Kalpa-Sutra authored by

Bhadrabhau Swami in V.S. 1216 is the oldest available artistic text of

India."

In

Rajasthan the first available pictorial text (on palm leaves) is

Savag-Pailikahan Sutt Chuniii (Shravak Pratikraman Sutra Churni), compiled in

the reign of Cubit Tej Singh at Ahar (Udaipur). Glimpses of his decorations are

enshrined in intricate carvings in the temples of Nagda and Chittor."

Another important text is Supasnah Chariyam (Suparshvanath Charitam) which was

painted and compiled in the reign of Mokkhal at Devkulpatak (Dilwara) in V.S.

1480 (A.D. 1422-23).

In this

text the influence of the Gujarat and Jain styles on Rajasthani paintings is

discernible. In the continuity of this style KaIpa-Sutrii of 1426 deserves

special mention. Its style of draping costumes is similar to that of the images

of Vijaya Stambha of Maharana Kumbha. Around A.D. 1450 one copy of Geet-Gvvind

and two of Bal-Gvpal-Stuti had been painted in Western India. This is the first

pictorial text of Lord Krishna which comprises the first seeds of preliminary

Rajasthani painting.

In 1451

Basant-Vilas painted in the Apbhransh style, whose famous background script was

compiled by Acharya Ratnagiri in Ahmedabad, makes special mention of the origin

of Rajasthani painting. In the history of Mewar, Maharana Kumbha (1433-1468)

had been highly acclaimed for having patronised poetry, music and architecture.

That such a great lover of the arts remained indifferent to painting is not

plausible. But in the absence of proof no concrete conclusion could be

inferred. Only a glimpse of frescoes could be visualised in the ruins of the

fort of Kumbhalgarh and the palace of Chittorgarh of that period.

In 1451

Basant-Vilas painted in the Apbhransh style, whose famous background script was

compiled by Acharya Ratnagiri in Ahmedabad, makes special mention of the origin

of Rajasthani painting. In the history of Mewar, Maharana Kumbha (1433-1468)

had been highly acclaimed for having patronised poetry, music and architecture.

That such a great lover of the arts remained indifferent to painting is not

plausible. But in the absence of proof no concrete conclusion could be

inferred. Only a glimpse of frescoes could be visualised in the ruins of the

fort of Kumbhalgarh and the palace of Chittorgarh of that period.

Up to

the 15th century this style of painting flourished in Rajasthan.

Using Jain and later Jain texts as the basis on which the painting was done,

this may be termed the Jain style, Gujarat style, Western India style or

Apbhransh style. Undoubtedly, the period from the 7th century to the

15th century saw an era of impressive growth of painting, iconography and architecture

in Rajasthan developed from the synthesis of original art and the traditions of

Ajanta-Ellora. From this point no distinction had ever been made between the

Rajasthan and Gujarat styles. In the regions of Bangur and Chhappan, many

artists from Gujarat had settled and were known as Sompuras. During the reign

of Maharana Kumbha, the legendary artist Shilpi Mandan migrated here from

Gujarat."

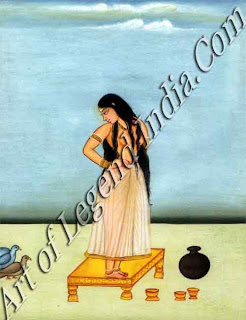

After

analysing the abovementioned pictorial texts from the 12th century

to the 15th century, it could be established that such paintings

contained the seeds of the Rajasthani styles of painting. The basis of most of

these paintings is Jain texts. In these paintings faces are savachashma, noses

resembling that of Garuda, tall but stiff figures, highly embossed breasts,

mechanical movements and poses, clouds, trees, mountains and rivers are

depicted. Red and yellow colours have been used frequently.

It is

difficult to tell where preliminary Rajasthani painting flourished in the 15th

century, but on the basis of other pictorial texts it may be stated that the

amended form of Rajasthani painting of that age had developed with some

distinct features. Adi Puran, decorated with 417 paintings, was a text in the Gujarati

style compiled in 1540. It was a beacon in the annals of Indian painting.

Although

influenced by Apbhransh style, this text, symbolic of Rajasthani painting in

respect of colour drawing, physical structure, depiction of nature, dress,

expression of sentiment, enjoys a prestigious position. Avadhi poetry Mrigvati

(decorated with 250 paintings) and pictorial lorchande belong to this category

of text. In the pictorial texts of Sanghrani-Sutra (1583) and Uttaradliyan

Sutra (1591), mention was made that a revised form of Rajasthani painting had

been created.

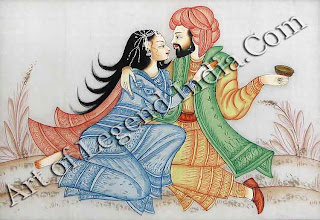

In

pictorial Chorpancha-Sika and Geet-Govind texts of that age, this school of

painting was appreciably represented. Regarding Rajasthani paintings, two very

significant texts are available. They are based on the Bhagwad.

The

first in 1598 and the other" in 1610 had probably been painted somewhere

in Rajasthan. In them developed the shape of Rajasthani painting with its

special characteristics that had emerged. Rag-Ma1a24 pictures painted by

Nasiruddin at Chavand, capital of Maharana Pratap, are the first available

specimens of paintings solely created on the soil of Rajasthan. Traditions of

the later period are noticed in the Mewar school.

On the

basis of these facts I submit that the birthplace of Rajasthani painting was

only Rajasthan, and Medapat (Mewar) was its centre of growth. In reality the

Rajasthani style was a new development of the Apbhransh style. In other words,

in place of the process of decline taking place in the 9th-10th

centuries, a phase of development had begun in the 15th century.

This revival might have taken place in Gujarat and southern Rajasthan (Mewar). Other

leading scholars identify Mewar with the origin and growth of Rajasthani

painting. Dr Goetz also firmly holds this opinion.

Those

tracts come under the hill states of Mewar, Banswara and Eder in southern

Rajasthan which were ruled by the Suryavanshi dynasty from ancient times. These

rulers continued to carry the torch of Indian culture even after the

disintegration of the 'Gupta Empire. Hence these rulers had absorbed the high

traditions of Ajanta and Ellora up to the medieval age.

Those

tracts come under the hill states of Mewar, Banswara and Eder in southern

Rajasthan which were ruled by the Suryavanshi dynasty from ancient times. These

rulers continued to carry the torch of Indian culture even after the

disintegration of the 'Gupta Empire. Hence these rulers had absorbed the high

traditions of Ajanta and Ellora up to the medieval age.

The

beginning of the pure Rajasthani style has been fixed between the latter half

of the 15th century and the early part of the 16th century, probably

around 1500. The Rajasthani style emerged from the Apbliransh style in Gujarat

and was influenced by the Kashmir style in the 15th century. Some

such paintings have been found in which the impact of the Mughal style is

nowhere discernible. The Bengali Ragini paintings of Bharat Kala Bha wan is one

of them. The above view of Raikrishan Dass seems authentic today as at the time

Rajasthani painting was taking shape Babar, grandfather of Akbar and founder of

the Mughal Empire in India, was born in 1463. Mehmood Begra, Sultan of Gujarat,

and Maharana Kumbha both earned great reputation as keen lovers of art. In the

same period painting had attained its zenith in Kashmir in the reign of Jainul

Abdin, when probably a cultural exchange between friendly states might have

taken place.

Because

of the emergence of the Rajasthani style in Gujarat and Mewar the dormant

consciousness of Indian painting awakened. It was a new version of the

Apbhransh style. From the point of expression of sentiments and depiction of

drawings, even though the Rajput style had emerged in its unique perspective,

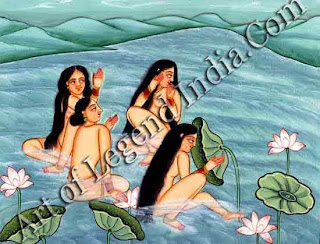

in selection of theme it had faithfully followed the Apbhransh style. Very

artistic paintings depicting Rag-Mala, Shringar, descriptions of Barah-Masa and

Krishna-Lila were the contribution of the Rajput style, which had its origin in

the Apbhransh style."

Some

scholars recognise the Gujarati style as the mother of Rajasthani painting and

its guiding spirit. Pramod Chandra says: "Gujarat was a principal centre

where Rajasthani painting acquired its prominent status . . ." Shri Manju

La! Ranchhor Dass Majumdar observes: "The Gujarat style gave birth to the

Rajput style, that rare beauty visible in drawings of mountain, river, sea,

fire, cloud, tree in the Rajput style originated from the Gujarat style."

In

regard to the impact of Jam art, many scholars stress the view that it made a

significant contribution to the growth of Hindu-Rajput art. Jain art was

responsible for incorporating creeper foliage in Indian painting. Later, having

surrendered the traditional heritance to the Rajput style, Jain art was lost in

oblivion. Dr Yajdani comments: "Jain art does not represent the best art

of its period." Hence it is argued that it might have surrendered its

traditions to the Rajput style, but it would be a great blunder on our part to

admit this view.

In

regard to the impact of Jam art, many scholars stress the view that it made a

significant contribution to the growth of Hindu-Rajput art. Jain art was

responsible for incorporating creeper foliage in Indian painting. Later, having

surrendered the traditional heritance to the Rajput style, Jain art was lost in

oblivion. Dr Yajdani comments: "Jain art does not represent the best art

of its period." Hence it is argued that it might have surrendered its

traditions to the Rajput style, but it would be a great blunder on our part to

admit this view.

Rajasthani

painting originated in the state of Rajasthan alone. Having been greatly

influenced by other styles of painting, it flourished greatly in this state. In

its growth the ancient history of the state and its geography played a major

role. On the heroic soil of the Rajputs, evidence of their chivalrous deeds and

the imprint of their civilization and culture in the shape of poetry, painting,

and architecture are scattered here and there.

Classification

The

origin and development of Rajasthani painting, like many other schools, did not

take place in one area, nor was it cultivated by only a few artists. In all

ancient towns and religious and cultural centres of Rajasthan painting

blossomed and flourished. Royal courts, religious centres, rulers, feudal lords

made a valuable contribution to the growth of Rajasthani painting, which

reached its pinnacle of glory in the 17th-18th centuries

after having enriched the styles and substyles of other erstwhile states, as a

result of which its coordinated shape came into existence.

In

regard to the classification of Rajasthani styles, scholars hold divergent

views. Artists of different states who painted in their own styles conform to

local condi-tions. The distinct characteristic of painting thus produced has

been termed the style of that particular region. In this way, several styles

came into prominence in Rajasthan, notably the Mewar, Marwar, Kishangarh,

Bundi, Kota, Jaipur, and Alwar schools had achieved great ascendancy.

Dr Moti

Chandra mainly recognises the Mewar, Bundi and Kishangarh schools. Scholars

like Dr Goetz, Karl Khandalawala, Ram Gopal Vijayavargia, Kumar Sangram Singh

added more styles and substyles pertaining to Marwar, Bikaner, Kota, Jaipur,

Uniara and Devgarh etc. In 1969 I worked on the authenticity of Alwar style.

Dr Moti

Chandra mainly recognises the Mewar, Bundi and Kishangarh schools. Scholars

like Dr Goetz, Karl Khandalawala, Ram Gopal Vijayavargia, Kumar Sangram Singh

added more styles and substyles pertaining to Marwar, Bikaner, Kota, Jaipur,

Uniara and Devgarh etc. In 1969 I worked on the authenticity of Alwar style.

From

the point of geographical and administrative conditions, Rajasthani painting

may be studied after classifying it in four parts. In actual practice it has

four principal schools in which many styles and substyles flourished and influenced

each other:

(1) The

Mewar school comprising Chavand, Udaipur, Devgarh, Nathdwara, Sawar styles and

substvles.

(2) The

Marwar school comprising Jodhpur, Bikaner, Kishangarh, Jaisalmer, Pali,

Naugore, Ghanerao styles and substyles.

(3) The

Hadoti school comprising Bundi, Kota, Jhalawar styles and substyles.

4) The

Dhundar school comprising Amber, Jaipur, Shekhawati, Uniara, Alwar styles and

substyles.

Having

placed the styles and substyles of the whole of Rajasthan within the purview of

the above schools, a detailed study of them could be undertaken. In the

medieval age it was quite natural for the small and big states of Rajasthan and

the neighbouring states to influence each other in the domain of culture.

Writer – Jay Singh Neeraj

In the

eighth century, the Early Western Chalukya power came to an end and the

Rashtrakutas under Dantidurga asserted themselves. Dantidurga was followed by

his uncle Krishna I who was not only a great ruler but was the creator of an

undoubtedly unique monument in the Deccan, the Kailasanatha temple at Ellora,

carved out of living rock. The glory of this monument has an effective

description in the Baroda grant of Karka Suvarnavarsha. It is here given that

'a gaze at this wonderful temple on the mountain of Elapura makes the

astonished immortals, coursing the sky in celestial cars, always wonder whether

"this is surely the abode of Svayambhu Siva and not an artificially made

(building). Has ever greater beauty been seen?" Verily even the architect

who built it felt astonished, saying, "The utmost perseverance would fail

to accomplish such a work again. Ah! how has it been achieved by me?" and

by reason of it, the king was caused to praise his name.

In the

eighth century, the Early Western Chalukya power came to an end and the

Rashtrakutas under Dantidurga asserted themselves. Dantidurga was followed by

his uncle Krishna I who was not only a great ruler but was the creator of an

undoubtedly unique monument in the Deccan, the Kailasanatha temple at Ellora,

carved out of living rock. The glory of this monument has an effective

description in the Baroda grant of Karka Suvarnavarsha. It is here given that

'a gaze at this wonderful temple on the mountain of Elapura makes the

astonished immortals, coursing the sky in celestial cars, always wonder whether

"this is surely the abode of Svayambhu Siva and not an artificially made

(building). Has ever greater beauty been seen?" Verily even the architect

who built it felt astonished, saying, "The utmost perseverance would fail

to accomplish such a work again. Ah! how has it been achieved by me?" and

by reason of it, the king was caused to praise his name.  The

remarkable similarity in details noticed in the Kailasa temples at Ellora and

Kanchi made Professor Jouveau Dubreuil look for and discover paintings in the

latter; how he found the clue to these in the former and how amply his search

bore fruit is only too well known, though the paintings may be fragmentary.

The

remarkable similarity in details noticed in the Kailasa temples at Ellora and

Kanchi made Professor Jouveau Dubreuil look for and discover paintings in the

latter; how he found the clue to these in the former and how amply his search

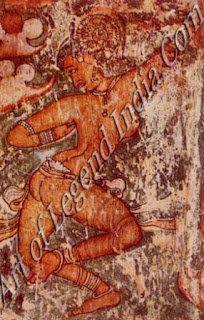

bore fruit is only too well known, though the paintings may be fragmentary.  Flying

Vidyadharas with their consorts, against a back-ground of trailing clouds,

musical figures and other themes closely follow the earlier Chalukya tradition.

A comparison of these Vidyadhara figures with similar ones from the Badami

caves of an earlier date would clearly reveal this. The colour patterns, the

composing of one dark against another fair, the muktayajnopavita of the male

and the elaborate dhammilla of the female figure, the flying attitude, etc.,

are all incomparable. The Jain cave towards the end of the group of caves at

Ellora has its entire surface of ceiling and wall covered with paintings with a

wealth of detail. There are scenes illustrating Jain texts and decorative

patterns with exuberant floral, animal and bird designs. These, along with the

cave, are to be dated a century after the Kailasa temple, the great monument of

the Rashtrakuta, Krishna.

Flying

Vidyadharas with their consorts, against a back-ground of trailing clouds,

musical figures and other themes closely follow the earlier Chalukya tradition.

A comparison of these Vidyadhara figures with similar ones from the Badami

caves of an earlier date would clearly reveal this. The colour patterns, the

composing of one dark against another fair, the muktayajnopavita of the male

and the elaborate dhammilla of the female figure, the flying attitude, etc.,

are all incomparable. The Jain cave towards the end of the group of caves at

Ellora has its entire surface of ceiling and wall covered with paintings with a

wealth of detail. There are scenes illustrating Jain texts and decorative

patterns with exuberant floral, animal and bird designs. These, along with the

cave, are to be dated a century after the Kailasa temple, the great monument of

the Rashtrakuta, Krishna.