‘I salute the sage Valmiki, who

perches like a cuckoo on the tree of poetry, singing “Rama! Rama!” and who,

though forever drinking from the ocean of the stories of Rama, is never sated'.

THE ORIGINAL RAMAYANA

I was composed in the distant past by the sage poet

Valmiki. Arranged into twenty-four thousand Sanskrit verses and divided into

six books, this sacred scripture is a cornerstone of the Hindu, or more

specifically the Vaishnava, faith. Ramayana, meaning 'Rama's travels',

documents Rama's triumph over the demon-king Ravana, thereby enacting his fate

as the ideal man and incarnation of the god Lord Vishnu. Memorized in full by

Valmiki's disciples, Ramayana has been passed down through generations. From

public readings to fireside retellings, this oral tradition is very much alive

today; in India, there are famous reciters of Ramayana who know the whole

story by heart.

I was composed in the distant past by the sage poet

Valmiki. Arranged into twenty-four thousand Sanskrit verses and divided into

six books, this sacred scripture is a cornerstone of the Hindu, or more

specifically the Vaishnava, faith. Ramayana, meaning 'Rama's travels',

documents Rama's triumph over the demon-king Ravana, thereby enacting his fate

as the ideal man and incarnation of the god Lord Vishnu. Memorized in full by

Valmiki's disciples, Ramayana has been passed down through generations. From

public readings to fireside retellings, this oral tradition is very much alive

today; in India, there are famous reciters of Ramayana who know the whole

story by heart.

The traditional way to

appreciate Ramayana is to hear it in its entirety from beginning to end.

Instructions are given for doing this in nine sittings, with breaks falling at

the traditional places. This is still common practice at the great 'Rama Katha'

festivals, which often attract tens, sometimes hundreds, of thousands of the

faithful for the full nine days. The intention is to become so immersed in the

stories of Rama that Rama, Sita and Hanuman come to life. This does not need to

end with the recital; it can be a constant process of remembrance. By

remembering Rama constantly one's whole life is sanctified, and the devotee

comes to see Rama everywhere, as Sita did. This stage of life is described by

Krishna: 'For one who sees Me everywhere and sees everything in Me, I am never

lost, nor is he ever lost to Me'.

In Indian villages it is

customary to hear stories from Ramayana in the evening. After sunset villagers

gather to hear the storyteller bring the characters to life; they cheer or cry

as the story unfolds, then go home to sleep and dream of Ramayana.

Since the time of Valmiki,

other poets have made their translations and adaptations of this epic, and

Ramayana long ago migrated across south-east Asia to countries such as Thailand

and Indonesia, each of whom have their own Ramayana literary traditions and

have made it a part of their own culture. In Thailand, an officially Buddhist

country, Ramayana dance-drama is the national dance, an inheritance of the

country's ancient Hindu past, and the Thai king traditionally models himself on

Rama. Indonesia, now predominantly Muslim, is famous for its shadow puppet

theatre depicting Ramayana.

In India, Ramayana passed into

each of the regional languages, such as Assamese, Bengali, Hindi, Kashmiri, Oriya,

Kannada, Telugu and Malayalam, where it generated separate literary and

religious traditions. Each region of the country has its own styles of Ramayana

drama, such as the famous Kathakali dancers of Kerala, and elaborate dramatic

productions are staged in the major cities. At festivals effigies of the

demon-characters Ravana and Kumbhakarna are burned, or actors dressed as Sita

and Rama are taken in procession. Ramayana is a staple of Indian cinema and the

serialized Ramayana on television, broadcast for 78 weeks during 1987-88,

brought the nation to a standstill for an hour each Sunday.

In all these ways, Rama has

entered the subconscious of India. This is why, so long after its creation,

Ramayana remains an essential part of Mother India, and the name of Rama echoes

on a million lips every day, as it did on the lips of Mahatma Gandhi as he

died.

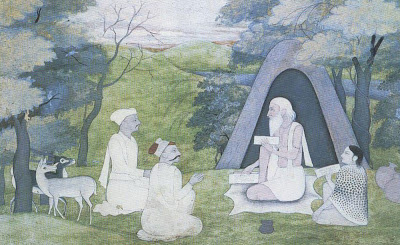

Rama is God incarnate, the

seventh incarnation of Vishnu. He chose to become human, and for the duration

of his human life to forget his divine identity, or so it seemed. He suffered

physical hardships and, when he lost his beloved Sita, a broken heart. On one

level Rama's journey is an allegory for the journey every soul must make. In

becoming human Rama shared in our human suffering and enacted the drama of our

own lives — each of us endures our own banishment, our own loss, faces our own

disillusions, and hopes eventually to learn acceptance of our lot and to find

ultimate redemption. Thus to hear or to witness Rama's struggles is to relive

our own lives, but in a divine context. Each episode in the story is

multi-layered, working through individual karma, or destiny, and the divine Lila,

or play, of Rama. In the same way, India's present-day Vedic sages point to

life itself as being the working out, for each of us, of our own personal web

of karma, desires and free will in accordance or in conflict with the will of

God.

THE

WEB OF KARMA

One great theme of Ramayana is

the working out of karma, the consequences of past deeds. The basic plot of

Ramayana is a simple struggle between good and evil the princess is kidnapped

by the great evil one, then rescued by her lover and the evil one is

vanquished; all live happily ever after. But it is not allowed to remain

simple. We discover that there are many layers of karma involved and dilemmas

to be faced, that the gap between good and evil is not as clear as we might

have thought, and that behind this simple story lies a cosmic purpose to be

fulfilled. At every step along the way we are tested emotionally and

intellectually.

Rama's banishment is the first

great hurdle. When his stepmother makes her extravagant demand for Rama to be

exiled, we wonder why he should submit to such a spiteful scheme. Our

sympathies go to Lakshmana, Rama's brother, who seems human in his intolerance

and his chiding of Rama. But Rama insists it is his duty to do as he is asked,

no matter how far-fetched that request may be. It is a matter of principle.

What we don't know at this stage, but later realize, is that here there are

greater forces at work. Dasaratha, Rama's father, has his own karma to answer

to. When he was a young man he carelessly killed a youth and was cursed by the

boy's father to die separated from his son. He had also unwisely pledged to

Kaikeyi when he married her, in addition to her two wishes, that her son could

be king. Unknown to us these consequences are being carried by Dasaratha, in

exactly the way we might be carrying unknown consequences from our own past.

Further, Rama's destiny as the incarnation of Vishnu requires him to leave

Ayodhya for his eventual confrontation with Ravana. There is also the position

of Sita. She had in a previous life, it is later revealed, sworn to bring about

the downfall of Ravana, who had violated her chastity when she was incarnated

as the divine ascetic Vedavati. In that previous birth she had performed

penances to obtain Vishnu as her husband. All these factors come into play at

the time of the banishment of Rama. Although it seems unjust, it is fated to

happen, in order to fulfil a higher purpose.

In Ramayana, evil is ambiguous,

and Ravana may not be as evil as he first appears. The story of Ravana's origin

is told in another ancient Vedic literature, the Srimad Bhagavatam. Ravana was

originally one of the gatekeepers of the spiritual realm of Vaikuntha, 'the

place without suffering', where Vishnu has his eternal home. He mistakenly barred

the exalted Kumara brothers from entering Vaikuntha and as a result was cursed

to fall to the material world. He was given the choice between enduring three

births as a demon or seven births as a godly being. In order to hasten his

return he chose to be born three times as a demon and to be killed each time by

Vishnu. ln his first birth he was Hiranya Kasipu, who was killed by the fourth

incarnation of Vishnu, Narasimha; in his second birth he was Ravana; and in his

third birth he was to become Kamsa, the enemy of Krishna. His fight with Vishnu

was therefore his way of assisting in the Lila, or divine play, of Vishnu, and

in this he was supported by Brahma, the creator. Ravana was born as the son of

Visrava, grandson of Brahma, and gained great powers From Brahma which enabled

him to terrorize the universe. With the help of his son Indrajit, also blessed

by Brahma, he defeated his half-brother Kuvera, the treasurer of the gods,

Indra the king of heaven and Yama the lord of death. Ravana's role as Vishnu's

adversary explains why, at his funeral, Rama found some kind things to say

about him.

In Ramayana, evil is ambiguous,

and Ravana may not be as evil as he first appears. The story of Ravana's origin

is told in another ancient Vedic literature, the Srimad Bhagavatam. Ravana was

originally one of the gatekeepers of the spiritual realm of Vaikuntha, 'the

place without suffering', where Vishnu has his eternal home. He mistakenly barred

the exalted Kumara brothers from entering Vaikuntha and as a result was cursed

to fall to the material world. He was given the choice between enduring three

births as a demon or seven births as a godly being. In order to hasten his

return he chose to be born three times as a demon and to be killed each time by

Vishnu. ln his first birth he was Hiranya Kasipu, who was killed by the fourth

incarnation of Vishnu, Narasimha; in his second birth he was Ravana; and in his

third birth he was to become Kamsa, the enemy of Krishna. His fight with Vishnu

was therefore his way of assisting in the Lila, or divine play, of Vishnu, and

in this he was supported by Brahma, the creator. Ravana was born as the son of

Visrava, grandson of Brahma, and gained great powers From Brahma which enabled

him to terrorize the universe. With the help of his son Indrajit, also blessed

by Brahma, he defeated his half-brother Kuvera, the treasurer of the gods,

Indra the king of heaven and Yama the lord of death. Ravana's role as Vishnu's

adversary explains why, at his funeral, Rama found some kind things to say

about him.

Another paradox in Ramayana is

the role of Vali. Vali is the enemy of Sugriva and an ally of Ravana. Yet he

could hardly be called evil, particularly as he is the son of Indra, the king

of heaven. Nevertheless Rama kills him. Vali misbehaved by banishing his

brother and stealing his wife, but to punish him with death seems extreme. But

once Rama has explained his reasons, Vali's anger dissipates and before he

dies, instead of seeking to blame Rama for killing him, he begs Rama's

forgiveness. Rama shows here that punishment can itself' be an act of love.

Putting this in the context of reincarnation, Rama explains that the karma of

the criminal must be redeemed by accepting punishment if' that karma is not to

be carried forward to the next life, where it would bring further suffering. 'A

sinner punished by the king is absolved and ascends to heaven,' declares

Ramayana, and adds: 'A sinner released by the mercy of the king is also

absolved, but the sin is transferred to the king.' In this context, Rama's

killing of Vali is an act of mercy, and Rama is acting as the all-knowing God

who dispenses justice with love.

FREEDOM

AND DUTY

A central theme of Ramayana is

the sacrifice of freedom for the sake of duty or honour. The Sanskrit word

approximating 'duty' is dharma, which has no equivalent in English. Roughly

translated, it means 'the essential purpose of life'. In Hindu society this

manifests as a set of principles governing behavior, such as the duty to obey

one's father or to protect one's dependants. These principles governing the

lives of the characters of Ramayana might seem oppressive in a modern context,

yet on a higher level they embody a spirit of service that can be an expression

of love. 'Love is as love does,' goes the saying. Love, if it is to be more

than sentiment, demands service.

A central theme of Ramayana is

the sacrifice of freedom for the sake of duty or honour. The Sanskrit word

approximating 'duty' is dharma, which has no equivalent in English. Roughly

translated, it means 'the essential purpose of life'. In Hindu society this

manifests as a set of principles governing behavior, such as the duty to obey

one's father or to protect one's dependants. These principles governing the

lives of the characters of Ramayana might seem oppressive in a modern context,

yet on a higher level they embody a spirit of service that can be an expression

of love. 'Love is as love does,' goes the saying. Love, if it is to be more

than sentiment, demands service.

Hence Rama's devotion to Sita

and his devotion for his people both dharma are in the higher sense an

expression of love demanding the sacrifice of his personal freedom. This

sacrifice of freedom is made not only by Rama, but by all the divine characters

of Ramayana. ‘When I was a child you took my hand and promised me your

protection,’ says Sita, 'and I have served you faithfully ever since.' Each

exemplify the ideal of service in a particular relationship, Hanuman as a

servant, Lakshmana as a friend and Sita as a lover. In the world of Ramayana

there is no escaping dharma, which is each person's path to salvation. And when

one duty appears to conflict with another, as when Rama's love for Sita

conflicts with his duty to his people, Rama, and each one of us, is tested.

For many Hindus, Hanuman is the

symbol of selfless service to God. It is no accident that a monkey should be

accorded this honour: love transcends social standing or even race or species.

When Jatayu, the faithful vulture who protects Sita, is killed by Ravana, Rama

says of him, 'This king of birds was a great soul who sacrificed his life for

my service. Souls such as this can be found everywhere, even among animals.'

If Rama, the incarnation of

Vishnu and Lord of the Universe, is occupied in service, the same can be said

of Krishna: 'There is no work prescribed for Me in the three planetary systems,

and there is nothing I lack yet I work. For if I should cease to work, these

worlds would be destroyed.' (Bhagavad Gita) This is the vision of God given by

the Vedic scriptures a God who voluntarily serves his creation. In this

spirit, Rama serves the demigods by killing Ravana, and he sets the example of

an ideal king, who always serves his subjects. His rule is remembered in India

as `Ramaraja', and remains the ideal to which all rulers aspire.

THE

IDEAL OF FOREST LIFE

The ever-present background to

Ramayana is the forest. During Rama's long exile he and Sita visit the ashrams

of sages, learning from them about spiritual life. The forest is never far

away, and with it the ascetic life of the sages. It is said that these sages,

who revered Rama as the incarnation of Vishnu and longed to be his devotees,

were later born as the gopi cowherd girls of Vrindavan, when they were able to

fulfil their desire by dancing in the forest with Lord Krishna. The beauty of

the forest is woven throughout Ramayana in luxuriant passages of detailed

imagery. But forest life is not easy, as Rama warns Sita at the outset; it

represents the ideal of simple living and renunciation of the world which is

the cornerstone of the Vedic spiritual path.

The forest could be interpreted

as the womb from which all life emerges and into which all will return. Sita

confesses her own fascination with the forest when she remembers the prediction

made about her when she was a child: 'When I was a little girl a holy woman

once came to our house,' she remembers, 'and I overheard her tell my mother

that one day I would live in the forest. It is my destiny.' Hanuman is a resident

of the forest, to which he returns at the end of the story, and indeed the

story is written in the forest. This spirit of abandoning the world and

returning to the simplicity of the forest beckons throughout. At the end of

Ramayana, after Sita and Rama have regained the comforts of Ayodhya, it

re-emerges when Sita asks to visit the ashrams, or hermitages, once more.

The final act of Ramayana is

itself one of leaving. Rama and his entourage leave this world in its entirety.

Perhaps this is Rama's profoundest message: this world is not to be enjoyed,

although some pleasure may be found here. Ultimately the world does not allow

itself to be enjoyed. We are all pitted against our own karma. Each of us

carries into this world our own burden of karma from past lives. Our task while

here is to assimilate this burden and come to terms with the lessons it has to

teach. Only then can we turn our attention to finding our true purpose. The

message is partly expressed by Vasistha when he advises Bharata after his

father's funeral: 'Life and death, joy and sorrow, gain and loss: these

dualities cannot be avoided. Learn to accept what you cannot change and give up

sorrow.'

SITA'S

SORROW

Valmiki prefaces Ramayana with

the story of its making. He tells us how, in a state of grief and dismay, he

composed a verse that gave expression to his emotion. This verse became the

model for the entire epic poem of Ramayana, the thread that runs through-out it

and which cannot be escaped: 'Hunter! Because you have so cruelly destroyed the

happiness of these birds your happiness will also be destroyed!

Valmiki prefaces Ramayana with

the story of its making. He tells us how, in a state of grief and dismay, he

composed a verse that gave expression to his emotion. This verse became the

model for the entire epic poem of Ramayana, the thread that runs through-out it

and which cannot be escaped: 'Hunter! Because you have so cruelly destroyed the

happiness of these birds your happiness will also be destroyed!

Even Sita, mother of the world,

is not exempt from sorrow. 'This body of mine was created only for sorrow,' she

cries. 'What sin have I committed that I should be made to suffer like this?'

Sita's suffering has been a source of perplexity to devotees for as long as

Ramayana has been told. Why should Sita, the eternal companion of' Vishnu, have

to undergo such suffering? Some devotees accept the explanation offered in the

Kurma Parana, where it is said that the original Sita was never taken by

Ravana; a demon like him would be incapable of' touching such a pure being. An

illusory Sita was substituted for her, we are told, while the real Sita was

sheltered by the Fire god. When the illusory Sita entered the fire after her

rescue, the Fire god returned the original Sita to Rama unharmed.

But I prefer another approach.

Sita's tribulations, in suffering separation from her lord, express the

unconscious feelings of all souls separated from God in this world. To

rediscover this inner sense of loss, of being separated from God, is the

essence of the spiritual path of bhakti, devotion to God. The feeling of being

abandoned by God, or of having abandoned God, is a recurrent theme in Vaishnava

devotion. Far from taking them away from God, this emotion actually brings

devotees closer to God through constant remembrance. When Hanuman first

encountered Sita he found that She does not see the monsters surrounding her,

or this heavenly garden, she sees only Rama.' This is the state of pure love,

where none but the loved one is present in every-thing. This is why Hanuman begs

Rama for the blessing to be able to remain in this world, even after Rama has

departed, but to 'always be devoted to you and no one else,' and again why

Lakshmana, in abandoning Sita, advises her to 'hold Rama always in your heart.'

This spiritual union with the beloved in constant inner remembrance transcends

physical union. It is the state of union with God which has been experienced by

all the great devotional mystics.

I was first introduced to Lord

Rama in my youth by my spiritual master, Srila Prabhupada, and take it as his

grace that I have now received the chance to serve Rama by writing this new

version of Ramayana. I chose for my source the original Ramayana of Valmiki, in

the two-thousand page English edition of the Gita Press, First published in

India in 1969. I am indebted to its translator, who out of modesty has remained

anonymous. I have faithfully followed his verse-by-verse translation, in both

pattern and content, while condensing it into modern English. I regularly used

to hear the story of Rama or watch it enacted on stage, but when at last I

turned to Valmiki's original text, in its English translation, I was

overwhelmed by its beauty and depth, which brought many realizations welling up

in my heart. I hope, that by putting Valmiki's story into modern English, and

making it accessible to a wider audience, I have helped others to taste

something of' the flavor of the original Ramayana and gain from it the

inspiration I have found.

PROLOGUE

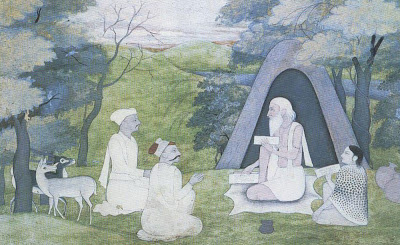

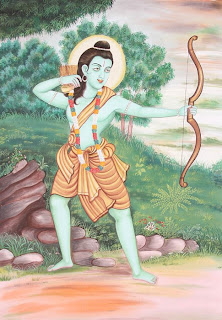

Let me tell you how this story

came to be told. Long ago the sage Valmiki lived with his disciples beside the

river Tamasa in the forests of Northern India. They lived a life of prayer and

meditation in simple huts woven from branches, leaves and grass Early one

morning the great Narada, who can fly at will through the sky to visit any

planet in the universe, appeared before Valmiki who greeted him with reverence

and offered him a seat. In the presence of this great personality Valmiki asked

a long-cherished question: 'Tell me, Narada, who is the greatest person in the

world? Who is accomplished, learned, powerful, beautiful, truthful, and cares

for all creatures? Who is without anger, yet sends fear into the hearts of

enemies?'

Narada smiled as he replied:

'The person you seek is extremely hard to find among ordinary mortals. There

is, however, a famous king by the name of Rama. He is strong and beautiful,

wise and compassionate, pure in character and loved by all. He has deeply

studied the ancient wisdom, is brilliant in archery and courageous in battle.

In gravity he is like the ocean, in constancy like the Himalayas and in

generosity like rain. Let me tell you about Rama: how he was forced to give up

his throne and live in the forest, how he rescued his wife Sita from the evil

Ravana and how he returned to rule his people with justice and love.

Valmiki sat in rapt attention as Mirada

recounted the wonderful story of Rama. At last he fell silent, saying, 'Whoever

hears the noble story of Rama's deeds will be blessed with success in this life,

and peace in the next.' Valmiki bowed low in gratitude as Narada left,

disappearing into the sky as the sun passes behind a cloud.

Valmiki called his disciple

Bharadvaja to accompany him to the river for his noon bath and meditation)

Here, Valmiki noticed a pair of cranes joyfully sporting and singing. As he

watched the birds, a hunter sprang from the forest and shot an arrow through

the heart of the male. The stricken bird fluttered to the ground and breathed

his last, and his mate wailed pitifully. Valmiki was filled with pain to see

such cruelty.

'Hunter! Because you have so cruelly destroyed

the happiness of these birds your happiness will also be destroyed!'

No sooner had the words left

his mouth than he stopped in surprise. He repeated the words again to himself

and then spoke them out loud to Bharadvaja, saying: 'These words of grief and

dismay have emerged in the form of a verse, with four feet of eight letters

each, which can be sung with a lute.'

As Valmiki returned to his

cottage, singing the verse to himself', he saw that he had another visitor,

even more illustrious than the first. It was Lord Brahma, the creator of the

universe and father of Narada. Again with respect Valmiki greeted his guest and

offered him a seat. As Brahma made himself comfortable, he heard Valmiki

quietly singing to himself his new-found verse.

'Ah!' he said, 'you have

created a verse expressing your grief. It was me who inspired you to do this.

The time has come for you to write the sacred and soul-stirring song of the

lives of Sita and Rama as you have heard it from Narada. As you do so, all its

details will be revealed to you through divine inspiration. Use this style of

verse and your song will be remembered as long as the mountains and seas

remain.' Then Lord Brahma left, and Valmiki and his disciples continued to sing

the verse in wonder, and the more they sang, the more their wonder grew.

The next day, Valmiki withdrew

to a silent and undisturbed place and sat facing east to absorb himself in

meditation. Entering a deep trance he saw in his mind's eye the Figures of Rama

and Sita. He saw Rama's father Dasaratha, with his queens surrounding him, all

laughing and talking. Then he saw Rama roaming in the forest in the company of

Sita and Lakshmana. Gradually the whole tale of Rama and Sita unfolded before

him in exquisite detail. At last he stirred from his trance.

Then Valmiki composed the story

as an epic poem. He divided it into six cantos and taught it to his disciples,

Kusa and Lava. They travelled the country reciting the story and their fame

spread, until one day they arrived in the city of Ayodhya and were brought

before King Rama himself. Rama, his three brothers, ministers and courtiers sat

silently as the boys began to sing. Kusa and Lava lifted their sweet voices in

clear notes, and here follows their sacred tale called Ramayana the journey

of Rama.

Writer - Ranchor Prime

I was composed in the distant past by the sage poet

Valmiki. Arranged into twenty-four thousand Sanskrit verses and divided into

six books, this sacred scripture is a cornerstone of the Hindu, or more

specifically the Vaishnava, faith. Ramayana, meaning 'Rama's travels',

documents Rama's triumph over the demon-king Ravana, thereby enacting his fate

as the ideal man and incarnation of the god Lord Vishnu. Memorized in full by

Valmiki's disciples, Ramayana has been passed down through generations. From

public readings to fireside retellings, this oral tradition is very much alive

today; in India, there are famous reciters of Ramayana who know the whole

story by heart.

I was composed in the distant past by the sage poet

Valmiki. Arranged into twenty-four thousand Sanskrit verses and divided into

six books, this sacred scripture is a cornerstone of the Hindu, or more

specifically the Vaishnava, faith. Ramayana, meaning 'Rama's travels',

documents Rama's triumph over the demon-king Ravana, thereby enacting his fate

as the ideal man and incarnation of the god Lord Vishnu. Memorized in full by

Valmiki's disciples, Ramayana has been passed down through generations. From

public readings to fireside retellings, this oral tradition is very much alive

today; in India, there are famous reciters of Ramayana who know the whole

story by heart.  In Ramayana, evil is ambiguous,

and Ravana may not be as evil as he first appears. The story of Ravana's origin

is told in another ancient Vedic literature, the Srimad Bhagavatam. Ravana was

originally one of the gatekeepers of the spiritual realm of Vaikuntha, 'the

place without suffering', where Vishnu has his eternal home. He mistakenly barred

the exalted Kumara brothers from entering Vaikuntha and as a result was cursed

to fall to the material world. He was given the choice between enduring three

births as a demon or seven births as a godly being. In order to hasten his

return he chose to be born three times as a demon and to be killed each time by

Vishnu. ln his first birth he was Hiranya Kasipu, who was killed by the fourth

incarnation of Vishnu, Narasimha; in his second birth he was Ravana; and in his

third birth he was to become Kamsa, the enemy of Krishna. His fight with Vishnu

was therefore his way of assisting in the Lila, or divine play, of Vishnu, and

in this he was supported by Brahma, the creator. Ravana was born as the son of

Visrava, grandson of Brahma, and gained great powers From Brahma which enabled

him to terrorize the universe. With the help of his son Indrajit, also blessed

by Brahma, he defeated his half-brother Kuvera, the treasurer of the gods,

Indra the king of heaven and Yama the lord of death. Ravana's role as Vishnu's

adversary explains why, at his funeral, Rama found some kind things to say

about him.

In Ramayana, evil is ambiguous,

and Ravana may not be as evil as he first appears. The story of Ravana's origin

is told in another ancient Vedic literature, the Srimad Bhagavatam. Ravana was

originally one of the gatekeepers of the spiritual realm of Vaikuntha, 'the

place without suffering', where Vishnu has his eternal home. He mistakenly barred

the exalted Kumara brothers from entering Vaikuntha and as a result was cursed

to fall to the material world. He was given the choice between enduring three

births as a demon or seven births as a godly being. In order to hasten his

return he chose to be born three times as a demon and to be killed each time by

Vishnu. ln his first birth he was Hiranya Kasipu, who was killed by the fourth

incarnation of Vishnu, Narasimha; in his second birth he was Ravana; and in his

third birth he was to become Kamsa, the enemy of Krishna. His fight with Vishnu

was therefore his way of assisting in the Lila, or divine play, of Vishnu, and

in this he was supported by Brahma, the creator. Ravana was born as the son of

Visrava, grandson of Brahma, and gained great powers From Brahma which enabled

him to terrorize the universe. With the help of his son Indrajit, also blessed

by Brahma, he defeated his half-brother Kuvera, the treasurer of the gods,

Indra the king of heaven and Yama the lord of death. Ravana's role as Vishnu's

adversary explains why, at his funeral, Rama found some kind things to say

about him. A central theme of Ramayana is

the sacrifice of freedom for the sake of duty or honour. The Sanskrit word

approximating 'duty' is dharma, which has no equivalent in English. Roughly

translated, it means 'the essential purpose of life'. In Hindu society this

manifests as a set of principles governing behavior, such as the duty to obey

one's father or to protect one's dependants. These principles governing the

lives of the characters of Ramayana might seem oppressive in a modern context,

yet on a higher level they embody a spirit of service that can be an expression

of love. 'Love is as love does,' goes the saying. Love, if it is to be more

than sentiment, demands service.

A central theme of Ramayana is

the sacrifice of freedom for the sake of duty or honour. The Sanskrit word

approximating 'duty' is dharma, which has no equivalent in English. Roughly

translated, it means 'the essential purpose of life'. In Hindu society this

manifests as a set of principles governing behavior, such as the duty to obey

one's father or to protect one's dependants. These principles governing the

lives of the characters of Ramayana might seem oppressive in a modern context,

yet on a higher level they embody a spirit of service that can be an expression

of love. 'Love is as love does,' goes the saying. Love, if it is to be more

than sentiment, demands service.  Valmiki prefaces Ramayana with

the story of its making. He tells us how, in a state of grief and dismay, he

composed a verse that gave expression to his emotion. This verse became the

model for the entire epic poem of Ramayana, the thread that runs through-out it

and which cannot be escaped: 'Hunter! Because you have so cruelly destroyed the

happiness of these birds your happiness will also be destroyed!

Valmiki prefaces Ramayana with

the story of its making. He tells us how, in a state of grief and dismay, he

composed a verse that gave expression to his emotion. This verse became the

model for the entire epic poem of Ramayana, the thread that runs through-out it

and which cannot be escaped: 'Hunter! Because you have so cruelly destroyed the

happiness of these birds your happiness will also be destroyed!

0 Response to "Introduction to Ramayana"

Post a Comment