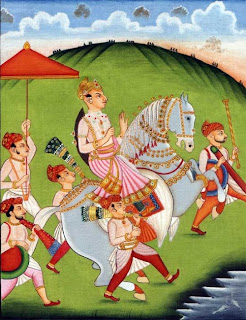

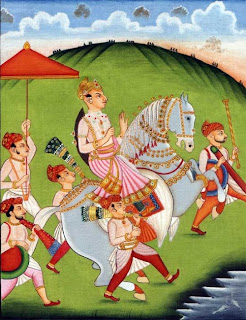

Despite great differences in particular

details of style and presentation, the princely portraits and paintings of

animals found in the Green collection reveal that visual specificity was but

one of the artists' concerns. The works created for Rajput and Mughal patrons

are carefully composed images, intended to convey particular kinds of

information about the subject. Of greater concern than specific physiognomic

details in a portrait might be the underscoring of the subject's status through

a particular manner of presentation and the depiction of certain accoutrements.

Such paintings were, in part, meant to fulfill functions not altogether

different from the promotional material created by today's PR agents. Thus, as

is true for princely imagery rendered at courts throughout the world, the

motivations behind the particular character of many Rajput and Mughal paintings

likely included a desire to project very calculated images of a ruler and his

realm.

Despite great differences in particular

details of style and presentation, the princely portraits and paintings of

animals found in the Green collection reveal that visual specificity was but

one of the artists' concerns. The works created for Rajput and Mughal patrons

are carefully composed images, intended to convey particular kinds of

information about the subject. Of greater concern than specific physiognomic

details in a portrait might be the underscoring of the subject's status through

a particular manner of presentation and the depiction of certain accoutrements.

Such paintings were, in part, meant to fulfill functions not altogether

different from the promotional material created by today's PR agents. Thus, as

is true for princely imagery rendered at courts throughout the world, the

motivations behind the particular character of many Rajput and Mughal paintings

likely included a desire to project very calculated images of a ruler and his

realm.

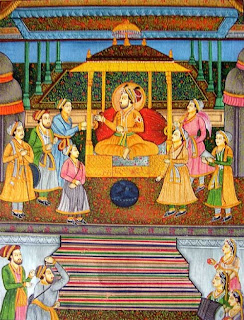

Mughal and Rajput patrons were extremely

interested in paintings with courtly themes as these works reflected the world

in which they lived. Portrayals of princely life first achieved prominence in

Indian painting under Mughal patronage and subsequently became an important

aspect of Raj put imagery as well. Such paintings in the Green collection

include aristocratic male portraits and depictions of animals, for horses and

elephants, as well as more exotic specimens, were often highly prized by their

royal owners.

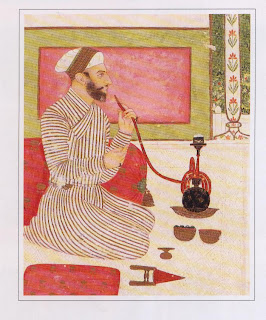

Among the manuscripts that the Mughal

emperor Akbar commissioned were a number of superbly illustrated histories of

his illustrious forbears—who included Chingiz (Genghis) Khan and Timur

(Tamerlane)—and of his own noteworthy reign as well as many individual

portraits. Indeed, a large portion of the production of the early Mughal

painting workshop was devoted to the depiction of courtly themes. An interest

in such themes was, in part, influenced by long-established Iranian traditions

of depicting royal persons and activities, such as princely figures engaged in

hunts or refined pursuits such as reading. Also influential were Western art

traditions, especially that of portraiture, introduced into the Mughal court in

the late sixteenth century. It was, how-ever, the keen interest of Akbar and

other Mughal rulers in images that reflected their particular sense of the

world around them that is most directly responsible for the popularity of

themes of courtly life and portraiture found in Mughal painting.

Before the

establishment of the Mughal dynasty there were no directly observed,

individualized portrayals in India, although certainly an interest in such

portraiture existed, as is demonstrated by written sources. Early Mughal portraiture

seems to have been unusual enough that Akbar's chief historian, Abul Fazl, was

compelled to record that not only did the emperor sit for his portrait, but he

also ordered the likenesses of all the grandees in the realm be painted. An

immense album of portraits was thus formed, and as Abul FazI notes, "Those

that have passed away have received new life and those who are still alive have

immortality promised them". Akbar and his descendants likely recognized

the value of such images in their evaluation of the character of the many

individuals involved in the administration of their immense realm as well as

their use in glorifying their own dynasty.

Individual

paintings eventually superseded the popularity of illustrated historical and

literary texts at the Mughal court as fewer and fewer such manuscripts were

commissioned. Favored instead were albums in which single paintings of various

subjects were combined with pages of beautifully calligraphed passages. Such

albums first became popular in the early seventeenth century during the reign

of the Mughal emperor Jahangir. Portraits and scenes of princely activities

were common subjects, as were floral and animal studies. Such paintings

continued to be rendered throughout the subsequent history of Mughal art.

Several works in the Green collection exemplify the type of portraits and

animal studies frequently made for Mughal patrons.

For Rajput patrons too, images of

themselves and the world in which they lived were extremely important. Even

though the interest in paintings with religious or literary subjects never

waned, a significant concern of many painters working for various Raj put

patrons was portraying the glorious person as of these rulers. Portraits

executed at the Raj put courts were at first largely inspired by Mughal

practice. One particularly early work in the Green collection, which dates from

the first part of the seventeenth century, is a clear demonstration of this

influence. In the eighteenth century a shift occurred at many Rajput courts

toward producing more portraits, and such works continued to be favored until

the decline of Rajput patronage of painting in the second half of the

nineteenth century.

Although influential, Mughal models were

freely adapted and transformed by Rajput artists. Indeed, even though many

specific Mughal elements made their way into Raj put schools, Raj put portraits

and depictions of princely pursuits also benefited from previously established

Indian traditions. Often a greater interest of Raj put painters in the inner

essence of their subjects rather than a faithful reproduction of their outward

appearance resulted in images of selective reality. Paintings in the Green

collection, such as an elegant rendering of royal worshippers and a powerful

but highly stylized portrayal of the Kota ruler Chattur Sal, demonstrate some

of the different ways in which Raj put painters departed from Mughal models.

However, neither Mughal nor Rajput paintings generally depict women with the

same specificity as male subjects. Females were largely defined by their roles

and were not usually distinguished as specific personalities but were instead

portrayed as ideal types.

In addition to portraits, other princely

subjects, such as elaborate festivals, entertainments, and hunts, were

frequently depicted by Raj put artists. Although these are subjects also

encountered in Mughal works, paintings such as a Basohli elephant combat and a

Kota hunt scene demonstrate the brilliant inventiveness to be found in the Raj

put expressions of these already established princely themes. Individual

depictions of courtiers, a popular Mughal theme, rarely seem to have been

painted by Raj put artists. Also unlike the Mughal tradition, historical scenes

were generally not as favored by Raj put patrons. A number of posthumously

executed portraits, however, reveals a similar interest in one's forbears.

Examples of this practice in the Green collection include posthumous portrayals

of the renowned rulers Sidh Sen of Mandi and Ajit Singh of Jodhpur. Such works

suggest that an awareness and promotion of the prestige of royal lineages was

also a concern of the Rajput courts.

Despite great differences in particular

details of style and presentation, the princely portraits and paintings of

animals found in the Green collection reveal that visual specificity was but

one of the artists' concerns. The works created for Rajput and Mughal patrons

are carefully composed images, intended to convey particular kinds of

information about the subject. Of greater concern than specific physiognomic

details in a portrait might be the underscoring of the subject's status through

a particular manner of presentation and the depiction of certain accoutrements.

Such paintings were, in part, meant to fulfill functions not altogether

different from the promotional material created by today's PR agents. Thus, as

is true for princely imagery rendered at courts throughout the world, the

motivations behind the particular character of many Rajput and Mughal paintings

likely included a desire to project very calculated images of a ruler and his

realm.

Despite great differences in particular

details of style and presentation, the princely portraits and paintings of

animals found in the Green collection reveal that visual specificity was but

one of the artists' concerns. The works created for Rajput and Mughal patrons

are carefully composed images, intended to convey particular kinds of

information about the subject. Of greater concern than specific physiognomic

details in a portrait might be the underscoring of the subject's status through

a particular manner of presentation and the depiction of certain accoutrements.

Such paintings were, in part, meant to fulfill functions not altogether

different from the promotional material created by today's PR agents. Thus, as

is true for princely imagery rendered at courts throughout the world, the

motivations behind the particular character of many Rajput and Mughal paintings

likely included a desire to project very calculated images of a ruler and his

realm.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Courtly Themes"

Post a Comment