It

is in this tradition that we find the present English rendition of the

Mahabharata. It is not a translation. The author, William Buck first became

acquainted with the Mahabharata through a chance reading of the Bhagavad-Gita

during a vacation in Nevada. Inspired by the poetry of this work he

subsequently read the whole Mahabharata and the Ramayana. He then set out to

make his own renderings. It is a retelling based on a translation of the

Sanskrit original published by Pratap Chandra Roy, published in the beginning

of this century. The slow and forceful pace of the Sanskrit original, its

honest, wise, and totally convincing outlook on the state of the world, its

descriptions of awesome battles and gruesome deaths as tragic yet natural

events in human experience, these are just a few of the features that have found

response in the hearts of millions of Asian people. Most Western renditions

have obscured the brilliance of the Sanskrit poetic constructions, but we have

all of this in William Buck's work. It is remarkable that a Westerner has been

able to uncover the nuggets of this Indian epic with such sensitivity. Like the

original, it deserves reading, rereading, and even reciting aloud, for it will

affect the reader at various levels of his awareness.

It

is in this tradition that we find the present English rendition of the

Mahabharata. It is not a translation. The author, William Buck first became

acquainted with the Mahabharata through a chance reading of the Bhagavad-Gita

during a vacation in Nevada. Inspired by the poetry of this work he

subsequently read the whole Mahabharata and the Ramayana. He then set out to

make his own renderings. It is a retelling based on a translation of the

Sanskrit original published by Pratap Chandra Roy, published in the beginning

of this century. The slow and forceful pace of the Sanskrit original, its

honest, wise, and totally convincing outlook on the state of the world, its

descriptions of awesome battles and gruesome deaths as tragic yet natural

events in human experience, these are just a few of the features that have found

response in the hearts of millions of Asian people. Most Western renditions

have obscured the brilliance of the Sanskrit poetic constructions, but we have

all of this in William Buck's work. It is remarkable that a Westerner has been

able to uncover the nuggets of this Indian epic with such sensitivity. Like the

original, it deserves reading, rereading, and even reciting aloud, for it will

affect the reader at various levels of his awareness.

The

Mahabharata is considered as an Indian epic which is most likely the biggest

ever composed in original Sanskrit. It is combined with the Ramayana (a second great

epic) which personify the perfume of Indian Cultural Heritage. The Mahabharata is

actually signifies the dynastic struggle for productive and wealthy land which

is situated near Delhi at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers and

struggle was between two teams (named as Kurus and the Pandavas) of a particular

Indian ruling family. The Struggle really ends in an awesome battle. Today, we

exactly don’t know when the battle took place.

The

Mahabharata (pronounced with the stress on the third syllable: Mahabharata) was

composed over a period of some four hundred years, between the second century

B.C. and the second century A.D., and already at that time the battle was a

legendary event, preserved in the folk tales and martial records of the ruling

tribes. The Indian calendar places its date at 3102 B.C., the beginning of the

Age of Misfortune, the Kaliyuga, but more objective evidence, though scanty and

inferential, points to a date closer to 1400 B.C.

At that time Aryan tribes had just begun to

settle in India after their invasion from the Iranian highlands. The land from

western Pakistan east to Bihar and south not farther than the Dekkhan was

occupied by Aryan tribes whose names are often mentioned in records much older

than the Mahabharata. The tribal communities varied in size and were each

governed by the "prominent families- (mahakulas) from among which one

nobleman was consecrated king. The kings quarreled and engaged in intertribal

warfare as a matter of course, their conflicts were sometimes prolonged

affairs, sometimes little more than cattle raids.

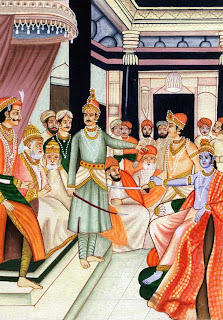

It

is in this context that the Bharata war took place. The Kurus were an ancient

tribe who had long been rulers of the area in the upper reaches of the Yamuna

River. The Pandus, or Pandavas, were a newly emergent clan living in

Indraprastha, some sixty miles southwest of the Kuru capital, Hastinapura.

According to the Mahabharata, the new aristocrats were invited to the court of

the ancient noble house of Kurt' to engage in a gambling contest. There they

were tricked first out of their kingdom and then into a promise not to

retaliate for twelve years. In the thirteenth year they took refuge at the

court of the Mistaya’s, where they allied themselves with the Kurus' eastern

and southern neighbors, the Pancalas. Together in a vast host they marched up

to Hastinapura, where they were met on Kuruksetra, the plain of the Kurus. Here

the Kurus and their allies were defeated.

In

bare outline that is the story of which the bard sings. But the composer of the

Mahabharata has portrayed the actions of the warriors in both a heroic and a

moral context, and it should be understood as a re-enactment of a cosmic moral

confrontation, not simply as an account of a battle. Unlike our Western

historical philosophy, which looks for external causes—such as famine,

population pressure, drought—to explain the phenomena of war and conquest, the

epic bard views the events of the war as prompted by observances and violations

of the laws of morality. The basic principle of cosmic or individual existence

is dharma. It is the doctrine of the religious and ethical rights and duties of

each individual. It refers commonly to duty enacted by religion. Today, every

person is expected to live based on his dharma and if any violation occur

caused disaster.

Hindu

society was classed into four castes, each with its own dharma. The power of

the state rested with the ksatriyas: kings, princes, free warriors and their

wives and daughters. Their dharma was to protect their dependents as rule

justly, always speak the truth, and struggle in wars. The priest caste was not

socially organized in churches or temples, but consisted of individual Brahmans

in control of religion. Among their other duties, they officiated at great

sacrifices to maintain the order of the world and accomplish desired goals.

They were also in control of education, could read and write, and taught

history according to their outlook on life. The Mahabharata in its final form

was largely the work of a Brahman composer, so we find in the peripheral

stories an emphasis on the power and glory of the Brahman caste, although in

the main story of the epic there is not one powerful Brahmin. The Vaisyas, of

whom we hear little in the Mahabharata, were merchants, townspeople, and farmers,

and constituted the mass of the people.

The

three upper castes were twice-born: once from their mothers and once from their

investitures with the sacred thread. The lowest caste, the Sutras, did menial

work and served other castes. They were Aryans, however, and their women were

accessible to higher-caste men: Vyasa was the offspring of a ksatriya and a

sudra, and so was Vidura. Outside the caste system were the "scheduled castes,"

the tribal people of the mountains, such as the Kiratas, as well as the

Persians and the Bactrian Greeks.

Besides

their caste dharma, people had a personal dharma to observe, which varied with

one's age and occupation. So we find a teacher-student dharma, a husband-wife

dharma, the dharma of an ascetic, and so on. One's relation to the gods was

also determined by dharma. The law books specify the various kinds of dharma in

detail, and these classifications and laws still govern Indian society.

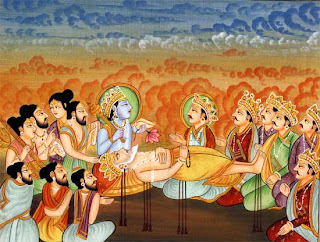

The

Hindu system of eschatology is often expounded in the Mahabharata. In brief, it

is the doctrine of the cycle of rebirths (samsara), the doctrine of the moral

law (dharma), which is more powerful than even the gods. The moral law sustains

and favors those creatures that abide by it, while thwarting those that

trespass. Its mechanism is karma, the inexorable law that spans this life and

the afterdeath, working from one lifetime to another, rewarding the just and

making the evil suffer. In this Hindu universe those in harmony with dharma

ultimately reach a state in which rebirth is not necessary any more. If,

however, the forces of evil are too strong, the moral law reasserts itself and

often uses forceful means to restore harmony where it has been lost. To accomplish

that, often a being of a higher order, a god, who in his usual manifestation

has no physical body, takes birth among the people and becomes an avatara, a “descent”

of his own power on earth. Often the physical manifestation is not aware of his

divine antecedents, but discovers them in the course of his life on earth.

Therefore an avatara has many human qualities, including some that by our own

standards would be less than divine: hostility, vengefulness, and an

overweening sense of self-importance. These qualities are necessary for him to

confront confidently the forces of evil, the asuras, who have taken flesh also

and appear as bitter enemies committed to a battle to the end.

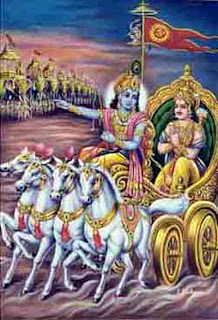

The

emphasis on morality in the Mahabharata brings with it considerations of the

nature of the divine. There are many gods; the Indian pantheon is overwhelming

in its diversity and vagueness. At the highest level of creation are the gods

(devas), who are in continual conflict with the demonic forces, the auras.

Among the gods, Vishnu, Siva, and Indra are especially important. Vishnu is

mainly manifest through his incarnation as Krishna. He is a supreme god worthy

of love and devotion. Siva is also a supreme god, but represents the ascetic

side of Indian religion. He dwells on a mountain, dresses in a tiger skin, and

wears a characteristic emblem, the trident, still carried by Indian mendicants.

The third eye in the middle of Siva's forehead scorches his enemies. Indra is

in name the king of the gods, but in fact his importance had declined by the

time of the Alahabharata, although he remained a principle god. In the

Mahabharata he is the god of rain and father of Arjuna, a Pandava.

Less powerful are the elemental gods of fire

(Agni), wind (Vayu), water (Varuna), sun (Surya), and moon (Soma). Kama is the

god of love. Unlike the gods in Western mythologies, the prominent Indian gods

are difficult to characterize. Although they are assigned obvious functions as

powers, their spheres of power and their characteristics overlap because they

are ultimately all manifestations of the universal principle, Brahman, the

universal soul or being to which individual souls will be reunited after the

illusion of time and space has been conquered.

At

a lower level, still divine but progressively less lofty, are the hosts of the

Gandharvas, Apsarases, Siddhas, Yaksas, and Raksasas. The first three classes

are usually benevolent to mankind. Gandharvas play heavenly music to which the

nymphs, the Apsarases, dance. Indra also uses the Apsarases to seduce ambitious

ascetics who, by their severe self-castigation, have accumulated so much

spiritual power that it becomes a threat to Indra's supremacy; as a result of

seduction the anchorite loses his power. Yaksas are sprites,dryads, and naiads.

Raksasas are malevolent demons who prowl around the sacrificial altars or in

other ways disturb human beings.

Humans

look at the gods as powers to be appeased or controlled, with the exception of Vishnu,

who is simply adored. Gods often interact with humans, marry them, give them

weapons, invoke their assistance or aid them. At times gods interact with men

through the intermediary of wise old men, sages whose advice was obeyed by

prudent warriors who would not violate the will of the gods in order to avoid

incurring the sage's curse. Upon his death, the ancient hero expects to go to

Indra's heaven, where there is feasting and rejoicing.

Rivers

and other landscape features are personified and function as both divine and

semi-divine beings and as natural phenomena. In the Mahabharata gods

communicate with men, animals talk and are sometimes real animals, some-times

human beings or gods. The story often moves into an idealized land where heroic

feats, deeds of velour and physical strength are regarded with awe and fear.

These incidents foster a sense of marvel in the reader: we are transported into

an idyllic world where illusion and reality cannot be separated.

The

Mahabharata should be understood as a moral and philosophical tale as well as

an historical one. Only in this way can we appreciate the significance of the Bhagavad-Gita,

the Song of the Lord, which is part of the Mahabharata, but which is usually

excerpted and read as an independent religious work. In India, the Mahabharata

as a whole has been regarded for centuries as a religious work, to the extent

that a medieval poetic theoretician characterizes its main sentiment (rasa) not

as heroism but as tranquility (santi).

Between

the time of the events described in the epic and the time the Mahabharata was

composed, social conditions had changed considerably. India was no longer a set

of tribal communities; it had become subdivided into large regions (janapadas)

ruled by kings who had become absolute monarchs. The conquests of King Asoka

and Chandragupta Maurya, which united large areas of India under one ruler, had

paved the way for the emergence of a national consciousness. "Dear to all

men is Bharata land, as it was to the god Indra, Father Manu and the mighty

warriors of old," says the poet. And although the Indian world was by now

interacting with the world around it, the most important part of the world was

still Bharata, the land of the Aryans, which was now concentrated south of the

Himalayas and north of the Vindhya Mountains, between the desert in the west

and the swamps of Bengal in the east.

The

Mahabharata did not remain an exclusively Sanskrit work. Within a few centuries

of its composition it was translated and paraphrased into other Indian

languages: the Dravidian languages of South India, and the Indo-Aryan languages

that succeeded Sanskrit historically in the north. Stories were adapted for

dramatization, folksinger’s com-posed ballads in their own tongues, preachers

and politicians made use of its philosophy. Thus the Great Epic gradually

spread by word of mouth from village to village, from kingdom to kingdom, from

region to region. It was recited in courts during great festivals and sacrifices

honoring a king (indeed, even as the Mahabharata is told as a story heard by

the bard at a great sacrifice.) Jams and Buddhists found a place for it in

their non-canonical literature, and as the Indian empire expanded from the

first years of the Christian era onward, the Mahabharata and its sister epic,

the Ramayana, accompanied the itinerant merchants. On the trade routes to

Europe, to Burma, to Thailand and Vietnam, to the spice islands of the western

Pacific the bards followed the traders, and later, when colonial kingdoms were

established in these tropical countries, they found a place at the kings'

courts. The profound moral message of the Mahabharata became identified with

the power of the ruling dynasties, and the epics were often translated into the

languages of the colonized countries. Gradually the Mahabharata became part of

the literature of the receiving country: the epic was reworked, rewritten, condensed

and phrased in contemporary terminology and in terms of the adopting culture.

It

is in this tradition that we find the present English rendition of the

Mahabharata. It is not a translation. The author, William Buck first became

acquainted with the Mahabharata through a chance reading of the Bhagavad-Gita

during a vacation in Nevada. Inspired by the poetry of this work he

subsequently read the whole Mahabharata and the Ramayana. He then set out to

make his own renderings. It is a retelling based on a translation of the

Sanskrit original published by Pratap Chandra Roy, published in the beginning

of this century. The slow and forceful pace of the Sanskrit original, its

honest, wise, and totally convincing outlook on the state of the world, its

descriptions of awesome battles and gruesome deaths as tragic yet natural

events in human experience, these are just a few of the features that have found

response in the hearts of millions of Asian people. Most Western renditions

have obscured the brilliance of the Sanskrit poetic constructions, but we have

all of this in William Buck's work. It is remarkable that a Westerner has been

able to uncover the nuggets of this Indian epic with such sensitivity. Like the

original, it deserves reading, rereading, and even reciting aloud, for it will

affect the reader at various levels of his awareness.

It

is in this tradition that we find the present English rendition of the

Mahabharata. It is not a translation. The author, William Buck first became

acquainted with the Mahabharata through a chance reading of the Bhagavad-Gita

during a vacation in Nevada. Inspired by the poetry of this work he

subsequently read the whole Mahabharata and the Ramayana. He then set out to

make his own renderings. It is a retelling based on a translation of the

Sanskrit original published by Pratap Chandra Roy, published in the beginning

of this century. The slow and forceful pace of the Sanskrit original, its

honest, wise, and totally convincing outlook on the state of the world, its

descriptions of awesome battles and gruesome deaths as tragic yet natural

events in human experience, these are just a few of the features that have found

response in the hearts of millions of Asian people. Most Western renditions

have obscured the brilliance of the Sanskrit poetic constructions, but we have

all of this in William Buck's work. It is remarkable that a Westerner has been

able to uncover the nuggets of this Indian epic with such sensitivity. Like the

original, it deserves reading, rereading, and even reciting aloud, for it will

affect the reader at various levels of his awareness.

William

Buck has, of course, condensed the story. The old translation from which he

worked covers 5800 pages of print, while his own book is less than a tenth that

length. But by and large, Buck's rendition reflects the sequence of events in

the Sanskrit epic, and he uses the traditional techniques, for instance, of

stories within stories, flashbacks, moral lessons layed in the months of

principal characters. In detail, however, there are differences between the

two, which makes it unwise to use this book as an exact reference work. William

Buck has excerpted passages without trying to be complete; so many passages

have been left out or altered to fit the shortened version. One of the parts

omitted is the Bhagavad-Gita.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Introduction to Mahabharata"

Post a Comment