Indian

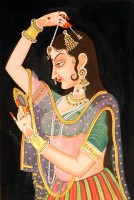

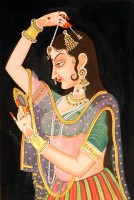

Paintings often depict a complete world, a world constructed rather than

depicted realistically and sometimes a completely imaginary one. Divided

thematically into religious, romantic, musical, and courtly subjects, the

paintings provide glimpses into some of the many worlds painted by Rajput and

Mughal artists in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. Many delighted in

verdant nature, in a courtyard garden, or in a lush forest after the monsoon. The

sixth-one paintings reveal various scenes as they appeared before the mind’s eye

of the artist: a shy Radha approaching Krishna; a lover tearing through the

woods to a tryst in the night; a ragini dancing in the forest amid musical

accompanies; a price on a tiger hunt.

Indian

Paintings often depict a complete world, a world constructed rather than

depicted realistically and sometimes a completely imaginary one. Divided

thematically into religious, romantic, musical, and courtly subjects, the

paintings provide glimpses into some of the many worlds painted by Rajput and

Mughal artists in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. Many delighted in

verdant nature, in a courtyard garden, or in a lush forest after the monsoon. The

sixth-one paintings reveal various scenes as they appeared before the mind’s eye

of the artist: a shy Radha approaching Krishna; a lover tearing through the

woods to a tryst in the night; a ragini dancing in the forest amid musical

accompanies; a price on a tiger hunt.

The

Indian paintings (often wrongly characterized as miniatures) discussed were

created mostly by unknown artists between about 1550 and about 185o. The

patrons of these works of art also are by and large unknown as individuals. In

general, however, they were members of ruling families and courtiers, of both

sexes, Hindus as well as Muslims. In fact, the role of women patrons in Indian

painting is yet to be properly assessed. Over three decades ago William Archer,

noting the power of Indian painting to charm both sexes, guardedly stated that

while Indian women also viewed it, it owed “its origins to masculine stimulus”.

Although the evidence is not abundant, there is little doubt that women too

patronized the various arts, including painting. A well-known instance is

Princess Jahanara, the eldest daughter of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan.

The

paintings in the Green collection consist mostly of book illustrations and

folios from albums. Small in scale, like European watercolors or Japanese

prints, they are easily portable. Therefore, a series or picture found in one

court may have been made somewhere else. They were never hung up on walls, but

held in hand and viewed intimately. In fact, the patron usually held a painting

at the same oblique angle when viewing as the artist did when painting it. When

not being looked at, the pictures were bundled up and stored in libraries or

special storerooms in the palace or mansion. They were, therefore, well

shielded from light, which is one reason why some of the pictures, although

three or more centuries old, are remarkably well preserved. (In some cases

where the storage conditions were less than ideal, the pictures were adversely

affected.)

The

small scale of the pictures does not mean that they are not technically

complex. The support of all the pictures is paper, and the pigments are water

based, though they are more opaque than English watercolors. Indian artists

also enriched their palette with gold,and urn ii the middle of the nineteenth

century, when European commercial paints were introduced, most pigments were

derived from plants and minerals with the exception of a pungent yellow called

peon, which was extracted from the urine of cows fed mangos. In their rich

detailing Indian pictures more often approximate the art of the European

miniature rather than that of the watercolor.

Many

of the pictures have inscriptions, which may or may not be relevant. There is

no rule governing the placement of textual material: inscriptions can occur on

the front and/or the back of a painting. In some cases the text is simply a

label identifying the subject, added either on the front or the back; in

others, it may be a verse or verses, often from a work of literature, briefly

describing the theme or recounting the story of the picture. Whereas some

pictures relate to their text closely, others seem to deviate significantly.

Occasionally an inscription provides us with relevant art-historical

information, such as the identity of the sitter or the name of an artist or a

date. In albums specially prepared for Muslim patrons, panels of poetry are

often pasted around a picture, but rarely are they related.

It

is customary to divide these paintings into two broad categories: Mughal and Raj

put. The expression Mughal (or Mogul) is the designation of the Muslim dynasty

founded by Babur, a Central Asian Turkic invader, in 1526. His grandson Akbar expanded

his inheritance to build an enormous pan-Indian empire that included parts of

Afghanistan in the northwest and extended south into the Deccan plateau. All

the important Decanis Muslim kingdoms, however, were not absorbed into the

Mughal Empire until the 168os, during die rule of Aurangzeb (1658-1707). the

last great Mughal emperor. After Aurangzeb, Mughal authority declined steadily

until the British united much of the subcontinent under their crown in 1858.

Pictures and books prepared for the emperors, their Muslim courtiers, and later

for independent Muslim rulers in north India are generally categorized as

Mughal. Mughal paintings have been further subdivided by art historians into

imperial, sub imperial, provincial, popular, and later Mughal. A parallel

tradition of painting flourished in the Islamic courts of the Deccan and is

usually categorized as Deccan.

During

the Mughal period, much of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Rajasthan

was peppered with semi-independent Hindu states of different sizes and power. The

rulers of these states, who belonged to various clans, are known collectively

as Rajput, derived from the word rajaputra, meaning "prince". In

the early decades of this century the noted art historian Amanda K.

Coomaraswamy used the term Rajput to describe paintings that were done for the

Raj put patrons. Pictures were also painted for the Hindu courts in that

section of the western Himalayas that stretches across several states today

(Pakistani and Indian Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttar

Pradesh). These pictures from the hills are generally referred to as Pahari,

the Adjectival form of the word pahad, meaning "hill".

During

the Mughal period, much of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Rajasthan

was peppered with semi-independent Hindu states of different sizes and power. The

rulers of these states, who belonged to various clans, are known collectively

as Rajput, derived from the word rajaputra, meaning "prince". In

the early decades of this century the noted art historian Amanda K.

Coomaraswamy used the term Rajput to describe paintings that were done for the

Raj put patrons. Pictures were also painted for the Hindu courts in that

section of the western Himalayas that stretches across several states today

(Pakistani and Indian Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttar

Pradesh). These pictures from the hills are generally referred to as Pahari,

the Adjectival form of the word pahad, meaning "hill".

Under

the inspired patronage of the emperor Akbar the Mughal painting work-shop

achieved a brilliant synthesis of Persian, Indian, and European traditions. The

early Mughal workshop, which became an active center for book production,

employed a large number of native artists who worked under the direction of

masters brought from Iran. In addition to the fact that the Mughals' taste was

Persian, most of the books copied and illustrated were also Persian. The

Mughals preferred books of fables and cosmological subjects, epics and

romances, historical sagas and chronicles, and, of course, poetry. Like most

cultured Muslims, the Mughals also admired calligraphy, and examples of fine

penmanship were collected and assembled in albums. Moreover, the albums

included portraits of both humans and animals as well as flower studies At

first heavily influenced by Persian aesthetics, by the 158os Mughal artists

were exposed to European paintings and prints. The presence of European

miniature portraits and Akbar's own requirements to become familiar with his

courtiers contributed to the development of realistic portraiture in Mughal painting.

The

type of pictures that the Mughals encountered in India is best exemplified in

the Green collection by two illustrations from a Bhagavatapurana, a Hindu

religious text. This style, characterized by a limited palette, simple

compositions, and stylized figures, continued to be favored by Hindu patrons

well into the first quarter of the seventeenth century, after which, at some of

the Raj put centers, the artists became more aware of the "dramatic,

objective, and eclectic" as well as more painterly Mughal style. The

degree to which they absorbed Mughal stylistic elements differed at different

centers, depending upon the taste of the patron as well as the artists' own

aesthetic preferences and training. In some schools, such as at Malwa, the

influence was not strongly felt until the end of the seventeenth century, while

in the Hill States it was manifested later still. Notwithstanding the

interaction with Mughal painting, it is easy to recognize in Raj put pictures,

as Coomaraswamy pointed out long ago, "a great variety of motifs, compositions,

and formulae that occur commonly in much older Indian works or correspond to

the phraseology of classical rhetoric.

Mughal influence was not simply one of style

but also of subject. Until the seventeenth century both Hindu and Jain patrons

showed a marked preference for religious books, although some secular works

from the period have also survived. Inspired by Mughal tastes, Raj put

paintings began to depict court scenes, festivals, and other subjects of

worldly nature. Secular themes portrayed in Raj put pictures, however, are more

symbolic and idealized and are not as graphic and realistic as they are in

Mughal pictures. Moreover, Rajput depictions of romantic, rhetorical, or

musical themes were often given a strongly religious color. The archetypal

heroes and heroines (nayakas and nayikas), even if described in mortal

contexts, were frequently identified with the divine figures of Krishna and

Radha. In the pictures from some states, such as Kota and Kishangarh , the

rulers themselves were identified with Krishna.

The development of painting in the many Rajput

courts is a complex issue and still subject to debate. Although attempts have

been made recently to distinguish styles of Pahari painting by families of

artists,' by and large Raj put paintings are still classified simply by the

semi-independent princely states that were merged into either India or Pakistan

when the British left the subcontinent in 1947. Thus, in the catalogue entries

names such as Basohli, Bikaner, Jodhpur, or Kangra denote the states where the

picture may have originated. Names of artists occur more commonly on Mughal

than Raj put works. Although families of artists may have been attached to a

court, there is strong evidence of the migration of artists from one state to

another in the hills. Moreover, as at least one artist in Rajasthan is known to

have moved from one court to another, it is very likely that others did too.

Painters also accompanied their patrons on duties away from their home courts,

such as military campaigns. It should further be noted that art moved about

freely from one state to another, especially in the form of presents or as part

of bridal trousseaus.

Since a large number of Rajput paintings has

emerged from royal collections, it would not be unjustified to assume that

rulers and their families were the major patrons. However, other courtiers as

well as educated and affluent merchants must have been interested in the arts,

and some works may have been made available in the bazaars for general

consumption. Although some artists enjoyed special relationships with their

patrons and may even have held elevated positions at court, generally the

professional artist did not have a higher status than a cook, a carpenter, or a

gardener. As a matter of fact, in a Hindu household the cook had a much higher

social position if he was a Brahman. Artists generally belonged to lower

castes. At the Mughal court Iranian and Muslim artists enjoyed a greater

status, partly because of their religious and cultural kinship with the rulers

and partly because Islamic society has never been as socially stratified as

that of the Hindus. However, there are instances of some Hindu artists

attaining exalted positions at court and enjoying a more familiar relationship

with their patrons.

Since a large number of Rajput paintings has

emerged from royal collections, it would not be unjustified to assume that

rulers and their families were the major patrons. However, other courtiers as

well as educated and affluent merchants must have been interested in the arts,

and some works may have been made available in the bazaars for general

consumption. Although some artists enjoyed special relationships with their

patrons and may even have held elevated positions at court, generally the

professional artist did not have a higher status than a cook, a carpenter, or a

gardener. As a matter of fact, in a Hindu household the cook had a much higher

social position if he was a Brahman. Artists generally belonged to lower

castes. At the Mughal court Iranian and Muslim artists enjoyed a greater

status, partly because of their religious and cultural kinship with the rulers

and partly because Islamic society has never been as socially stratified as

that of the Hindus. However, there are instances of some Hindu artists

attaining exalted positions at court and enjoying a more familiar relationship

with their patrons.

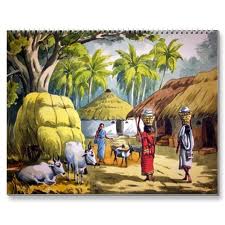

Whether

Mughal or Rajput, Indian pictures are fascinating for the variety and zest of

life they express. Whether they depict the material world or the mythic realm,

they attest to the limitless universe of the human imagination, and through

brilliant colors and forms they capture the spirit of the themes with admirable

candor. Displaying great delicacy, finesse, and lyrical charm, these small but

elegant pictures remain vivid evocations of a romantic past.

Whether

Mughal or Rajput, Indian pictures are fascinating for the variety and zest of

life they express. Whether they depict the material world or the mythic realm,

they attest to the limitless universe of the human imagination, and through

brilliant colors and forms they capture the spirit of the themes with admirable

candor. Displaying great delicacy, finesse, and lyrical charm, these small but

elegant pictures remain vivid evocations of a romantic past.

Indian

Paintings often depict a complete world, a world constructed rather than

depicted realistically and sometimes a completely imaginary one. Divided

thematically into religious, romantic, musical, and courtly subjects, the

paintings provide glimpses into some of the many worlds painted by Rajput and

Mughal artists in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. Many delighted in

verdant nature, in a courtyard garden, or in a lush forest after the monsoon. The

sixth-one paintings reveal various scenes as they appeared before the mind’s eye

of the artist: a shy Radha approaching Krishna; a lover tearing through the

woods to a tryst in the night; a ragini dancing in the forest amid musical

accompanies; a price on a tiger hunt.

Indian

Paintings often depict a complete world, a world constructed rather than

depicted realistically and sometimes a completely imaginary one. Divided

thematically into religious, romantic, musical, and courtly subjects, the

paintings provide glimpses into some of the many worlds painted by Rajput and

Mughal artists in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. Many delighted in

verdant nature, in a courtyard garden, or in a lush forest after the monsoon. The

sixth-one paintings reveal various scenes as they appeared before the mind’s eye

of the artist: a shy Radha approaching Krishna; a lover tearing through the

woods to a tryst in the night; a ragini dancing in the forest amid musical

accompanies; a price on a tiger hunt.  During

the Mughal period, much of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Rajasthan

was peppered with semi-independent Hindu states of different sizes and power. The

rulers of these states, who belonged to various clans, are known collectively

as Rajput, derived from the word rajaputra, meaning "prince". In

the early decades of this century the noted art historian Amanda K.

Coomaraswamy used the term Rajput to describe paintings that were done for the

Raj put patrons. Pictures were also painted for the Hindu courts in that

section of the western Himalayas that stretches across several states today

(Pakistani and Indian Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttar

Pradesh). These pictures from the hills are generally referred to as Pahari,

the Adjectival form of the word pahad, meaning "hill".

During

the Mughal period, much of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Rajasthan

was peppered with semi-independent Hindu states of different sizes and power. The

rulers of these states, who belonged to various clans, are known collectively

as Rajput, derived from the word rajaputra, meaning "prince". In

the early decades of this century the noted art historian Amanda K.

Coomaraswamy used the term Rajput to describe paintings that were done for the

Raj put patrons. Pictures were also painted for the Hindu courts in that

section of the western Himalayas that stretches across several states today

(Pakistani and Indian Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttar

Pradesh). These pictures from the hills are generally referred to as Pahari,

the Adjectival form of the word pahad, meaning "hill". Since a large number of Rajput paintings has

emerged from royal collections, it would not be unjustified to assume that

rulers and their families were the major patrons. However, other courtiers as

well as educated and affluent merchants must have been interested in the arts,

and some works may have been made available in the bazaars for general

consumption. Although some artists enjoyed special relationships with their

patrons and may even have held elevated positions at court, generally the

professional artist did not have a higher status than a cook, a carpenter, or a

gardener. As a matter of fact, in a Hindu household the cook had a much higher

social position if he was a Brahman. Artists generally belonged to lower

castes. At the Mughal court Iranian and Muslim artists enjoyed a greater

status, partly because of their religious and cultural kinship with the rulers

and partly because Islamic society has never been as socially stratified as

that of the Hindus. However, there are instances of some Hindu artists

attaining exalted positions at court and enjoying a more familiar relationship

with their patrons.

Since a large number of Rajput paintings has

emerged from royal collections, it would not be unjustified to assume that

rulers and their families were the major patrons. However, other courtiers as

well as educated and affluent merchants must have been interested in the arts,

and some works may have been made available in the bazaars for general

consumption. Although some artists enjoyed special relationships with their

patrons and may even have held elevated positions at court, generally the

professional artist did not have a higher status than a cook, a carpenter, or a

gardener. As a matter of fact, in a Hindu household the cook had a much higher

social position if he was a Brahman. Artists generally belonged to lower

castes. At the Mughal court Iranian and Muslim artists enjoyed a greater

status, partly because of their religious and cultural kinship with the rulers

and partly because Islamic society has never been as socially stratified as

that of the Hindus. However, there are instances of some Hindu artists

attaining exalted positions at court and enjoying a more familiar relationship

with their patrons. Whether

Mughal or Rajput, Indian pictures are fascinating for the variety and zest of

life they express. Whether they depict the material world or the mythic realm,

they attest to the limitless universe of the human imagination, and through

brilliant colors and forms they capture the spirit of the themes with admirable

candor. Displaying great delicacy, finesse, and lyrical charm, these small but

elegant pictures remain vivid evocations of a romantic past.

Whether

Mughal or Rajput, Indian pictures are fascinating for the variety and zest of

life they express. Whether they depict the material world or the mythic realm,

they attest to the limitless universe of the human imagination, and through

brilliant colors and forms they capture the spirit of the themes with admirable

candor. Displaying great delicacy, finesse, and lyrical charm, these small but

elegant pictures remain vivid evocations of a romantic past.

0 Response to "Introduction to Indian Paintings"

Post a Comment