An extensive literary tradition

developed in association with Ragamalas. Dating perhaps from the second century

of the common era, the Ragasagara (Ocean of melodies) by Dattila is the oldest

known text to personify and describe the melodies (Kaufmann 1968, p. 11). This

early example notwithstanding, most Ragamala texts date from the thir-teenth

century onward. The majority were written in Sanskrit or various dialects of

Hindi, with a few works or translations in Persian and Bengali also known

(Coomaraswamy 1923; Ebeling 1973, pp. 112-49; and Gangoly, I:I05—50). Among the

medieval Sanskrit texts, the most influential iconographic source for the

Ragamala paintings produced in the Rajasthani tradition were the Sangitadarpana

(Mirror of music) by Damodara Misra dating from about 1625 and the anonymous

Sangitamala (Garland of music) of about 1750. In the Pahari tradition, the

Ragamala of 570 by Kshemakarna (a court priest from Rewa, Madhya Pradesh;

popularly known also as Meshakarna) formed the basis for the radically

different pictorial imagery used.

An extensive literary tradition

developed in association with Ragamalas. Dating perhaps from the second century

of the common era, the Ragasagara (Ocean of melodies) by Dattila is the oldest

known text to personify and describe the melodies (Kaufmann 1968, p. 11). This

early example notwithstanding, most Ragamala texts date from the thir-teenth

century onward. The majority were written in Sanskrit or various dialects of

Hindi, with a few works or translations in Persian and Bengali also known

(Coomaraswamy 1923; Ebeling 1973, pp. 112-49; and Gangoly, I:I05—50). Among the

medieval Sanskrit texts, the most influential iconographic source for the

Ragamala paintings produced in the Rajasthani tradition were the Sangitadarpana

(Mirror of music) by Damodara Misra dating from about 1625 and the anonymous

Sangitamala (Garland of music) of about 1750. In the Pahari tradition, the

Ragamala of 570 by Kshemakarna (a court priest from Rewa, Madhya Pradesh;

popularly known also as Meshakarna) formed the basis for the radically

different pictorial imagery used.

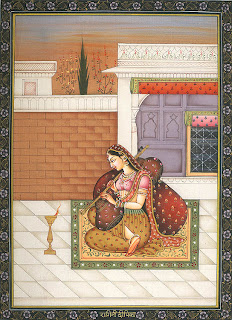

Many of the paintings in the

Green collection illustrate the typically Indian literary theme of personified

and poeticized musical melodies (ragas). Grouped in sets known as a Ragamala

(Garland of melodies), India's musical modes are a polymorphic form of artistic

creativity unique in the history of world culture. They combine music, poetry,

and painting in specific emotional and aesthetic correlations. The melodies are

historically the oldest component of the triad. They consist of notes arranged

in a particular sequence or structure, around which melodies expressing a

particular sentiment or ambience are improvised. Following the melodies, poetic

verses were composed to describe the appearance, personalities, and,

especially, the interpersonal relationships of the personified melodies. In

contrast to the music, the poetry associated with ragas was much more limited

in its extent and range of expression, serving originally to emphasize various

emotions associated with the melodies and, subsequently, functioning as a basis

for the visual imagery.

Paintings depicting the melodies were the last

of the three associated arts to develop. They were originally mounted as sets

in albums containing either thirty-six or forty-two folios. The sets were

conceived and organized in a system of "families." Each family is

headed by a male (raga), who has five or six wives (raginis) and sometimes

several sons (ragaputras) and daughters (ragaputris). This system of raga

families was traditionally used to determine the genders of the painted

personifications and pronouns used in the verses of poetry but is today much

less rigidly followed in musical classifications.

The names of the ragas are

derived from a variety of sources (Gangoly i: 72-79; Kaufmann, pp. 18-20; and

Pal 1967, pp. 8-9). The earliest method of naming the melodies often depended

on the beginning or dominant note of the composition, as in the Madhyamadi

Ragini, which begins with the note Madhyama (corresponding to F in Western

musical notation). In addition to this musical basis there are numerous other

rationales for the derivations of the ragas' names. Different geographical

regions or cities lent their names to melodies, as in Khambhavati Ragini, which

is derived from the ancient name of the coastal city of Cambay in Gujarat.

Seasons contributed their names, as in Vasant (Spring) Ragini (no. 31). Flowers

and animals lent their names, as in Kamala (Lotus) Ragini or Mayuri (Peahen)

Ragini. Religious associations influenced the names, as in Bhairavi Ragini,

which is dedicated to Siva (no. 5A verso). Tribal ties determined the names of

several melodies, as in Malavi Ragini, named after the central Indian tribe of

the Malavas. Musicians and royal patrons also gave names to new musical

creations, as in jaimpuri Todi Ragini, named for the Shargi kings of Jaunpur in

Uttar Pradesh (r. 1394— 1479). Finally, new names even resulted from the

bungling of copyists, as in Patamanjari Ragini, which was originally called

Prathama-manjari Ragini.

There are a number of underlying inspirations

and cultural correlations inherent to Ragamalas. The most basic involves the

time of day or season with which each melody is affiliated. Although these

symbolic associations were often ignored by poets and painters, they are

considered so sacrosanct by musicians that performing Dipak (Lamp) Raga (no. 5B

verso) at any time other than its prescribed midday is believed to incite

flames and cause disaster. The most influential thematic corollary to

Ragamalas, however, was the extensive literary tradition of ideal loving

couples (see introduction to Themes of Romance section), which classifies

female lovers (nayikas) and male lovers (nayakas) into two basic emotional

stereotypes: ecstatic lovers in union and forlorn ones in separation. Megha

Raga, for example, expresses the former, while Todi Ragini symbolizes the

latter. The set imagery for Ragamalas was occasionally recast in more

devotional garb with the inclusion of Krishna as the hero and Radha or various

goddesses as the heroine (nos. 32B, 39).

An extensive literary tradition

developed in association with Ragamalas. Dating perhaps from the second century

of the common era, the Ragasagara (Ocean of melodies) by Dattila is the oldest

known text to personify and describe the melodies (Kaufmann 1968, p. 11). This

early example notwithstanding, most Ragamala texts date from the thir-teenth

century onward. The majority were written in Sanskrit or various dialects of

Hindi, with a few works or translations in Persian and Bengali also known

(Coomaraswamy 1923; Ebeling 1973, pp. 112-49; and Gangoly, I:I05—50). Among the

medieval Sanskrit texts, the most influential iconographic source for the

Ragamala paintings produced in the Rajasthani tradition were the Sangitadarpana

(Mirror of music) by Damodara Misra dating from about 1625 and the anonymous

Sangitamala (Garland of music) of about 1750. In the Pahari tradition, the

Ragamala of 570 by Kshemakarna (a court priest from Rewa, Madhya Pradesh;

popularly known also as Meshakarna) formed the basis for the radically

different pictorial imagery used.

An extensive literary tradition

developed in association with Ragamalas. Dating perhaps from the second century

of the common era, the Ragasagara (Ocean of melodies) by Dattila is the oldest

known text to personify and describe the melodies (Kaufmann 1968, p. 11). This

early example notwithstanding, most Ragamala texts date from the thir-teenth

century onward. The majority were written in Sanskrit or various dialects of

Hindi, with a few works or translations in Persian and Bengali also known

(Coomaraswamy 1923; Ebeling 1973, pp. 112-49; and Gangoly, I:I05—50). Among the

medieval Sanskrit texts, the most influential iconographic source for the

Ragamala paintings produced in the Rajasthani tradition were the Sangitadarpana

(Mirror of music) by Damodara Misra dating from about 1625 and the anonymous

Sangitamala (Garland of music) of about 1750. In the Pahari tradition, the

Ragamala of 570 by Kshemakarna (a court priest from Rewa, Madhya Pradesh;

popularly known also as Meshakarna) formed the basis for the radically

different pictorial imagery used.

Ragamala paintings exhibit a

complex and variable imagery throughout the different geocultural regions of

India. Among the earliest surviving examples are those painted at various

subimperial Mughal workshops in northern India (nos. 31, 32A). Their

iconography accords with the majority of representations from Rajasthan (nos.

32B, 35, 40), Madhya Pradesh (nos. 33, 39), and the Deccan, which together

constitute the "Rajasthani tradition" (Ebeling 1973, pp. 56-62).

Images produced within this tradition typically portray romantic or devotional

scenes involving royal couples in a palatial set-ting complete with attendants.

Depictions of ragas in the Rajasthani tradition follow an iconographic order of

classification known as the "painters system," a term coined by a

leading specialist on Ragamala painting, Klaus Ebeling. Although it was the

prevailing ordering system in numerous Rajasthani and related ateliers and

forms the conceptual basis of approximately half of all of the known inscribed

Ragamalas, its paradigmatic literary origin remains unknown. Within the

Rajasthani tradition, a variant ordering subsystem was used for Ragamalas

produced at Amber (no. 34) and Jaipur. In addition, a second iconographic

system, attributed to an early medieval musicologist named Hanuman, was also

utilized for some twenty-five additional Ragamalas (Ebeling 1973, p. 18).

Ragamala paintings and drawings

made for the courts of Himachal Pradesh (nos. 36-38, drawings on versos of 5A-B),

which comprise the "Pahari tradition" (Ebeling 1973, pp. 272-96),

typically show individual or paired deities, people, and/or animals. The

conceptual source for the Pahari illustrations was Kshemakarna's Ragamala, in

which verses 12-97 personify and describe each musical mode, and verses 98-109

compare each melody to either the call of an animal or to a manmade sound

(Ebeling 1973, p. 64-78).

Owing to their complex imagery,

diverse geographical traditions, and centuries of development, Ragamala

paintings frequently exhibit conflicting regional variations for the same

melodies. Complicating matters even further is the fact that painters also

relied on oral traditions for their compositions, and thus there is often a

lack of correspondence between image and text. Perhaps in consequence, the

paintings are generally identified by labels or poetic passages that function

as a visualization or meditation aid (dhyana-mantra). The lengthy verses of

text found on the top or the back of paintings customarily start with a

quatrain (caupayi) whose second and fourth lines rhyme and end with a rhyming

couplet (doha) that gives the essence of the initial quatrain. Unfortunately,

even contemporary, and especially later, inscriptions are occasionally

inaccurate.

Today Ragamalas have

disappeared from the repertoires of Indian painters and poets. Only the musical

modes still burn with the flame of creativity.

Writer - Pratapaditya Pal

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Musical Modes Ragamala Paintings"

Post a Comment