UNDER THE INFLUENCE of the Jain

Tirthankaras many of the South Indian rulers accepted the Jaina religion and patronized

the erection of a large number of Jaina images and Jaina-Bastis in the Deccan

plateau. But, due to the efforts of Kumarilabhatta, Sankaracharya, Ramanuja

(Ramanujacharya) and others, Hinduism regained its lost position in the South,

and quite a large number of Shiva and Vishnu temples were built by the South

Indian rulers. Such was the case with the Hoysalas of the Karnataka and they

are one of the greatest builders of Hindu temples and Jaina-Bastis. They

constructed as many as fifty-three temples and seven Jaina-Bastis in different

parts of Karnataka. Let us therefore turn our attention to the art-treasures of

Belur Halebid and Somnathpur.

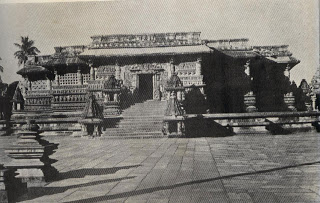

Belur (Beluhut or Velapura) is in the Hassan

district of the old Mysore State (now Kama taka). It was the capital city of

Ballala I and his younger brother Vishnuvardhana. In the epigraphs this city is

recorded as earthly Vaikuntha and Dakshina-Varanasi. The Chenna Kesava temple

at Belur is one of the most exquisite specimens of Hoysala art. It appears from

the inscription of the east wall near the entrance that king Vishnu-vardhana

constructed the temple and installed Vijaya-Narayana there in A.D. 1117. He did

this after his conversion to Vaishnavism from the Jaina faith by the celebrated

Ramanuja. Again, according to tradition he installed five Narayana images

(Pancha-Narayana-Pratishtha) at Belur, Talkad, Melkote, Tonnur and Gagag

(Gundlupet).

The Chenna Kesava temple is

situated in a court measuring 135.18 by 120.70 m. (443' 6" by 396') with a

high enclosure wall, and there are two other temples, Mandapas and lesser shrines.

There are two gates, one on the east (Elephant's Gate) and the other on the

north side with a very lofty tower (Gopuram) which was added later on by the

successors of Vishnuvardhana, under the influence of the Chola-Chalukya style.

The temple stands on a raised platform 0.91 m. (3ft.) in height, measuring

54.26 by 47.55m. (178' by 156'). The shrine consists of a Garbha-griha

(Adytum), a Sukhanasi (vestibule) and a Navaranga (central hall) which has

entrances from the east, south and north. The east entrance is for the priests

and devotees, the south for the "Friday entrance"

(Shukra-vara-bagilu) and the north is, "the Heavenly entrance"

(Svargada-bagilu). Manmatha and Rati are sculptured on the eastern doorway,

Hanu-mana and Garuda on the southern and female chauri-bearers on the northern.

The pediments have projected panels with Garuda flanked by Makaras and the

sculpture of Narasimha killing Hiranyakashipu (demon) on the east, Varaha

killing Hiranyaksha on the south, and Kesava on the north.

The temple wall from the

eastern doorway up to the north and the south entrances has a railed parapet

(Jagati) having beautiful friezes of elephants, a cornice with beadwork

surmounted by lion heads (Simha-lalatas) at intervals, and scroll work with

figures in every convolution. Another cornice is decorated with beadwork, and

small figures mostly of females. The projecting ornamental niches have

beautiful seated figures of Yakshas and Yakshinis. The eaves are decorated with

beadwork and thick creepers running along the edge of the upper slope having

miniature turrets, lions and many other small images. The rail also contains

figures; some are Maithuna figures (amorous couples) in panels and with

ornamental bands. But the elephant frieze is strangely enough left blank

throughout the temple. The rail to the right of the east entrance beautifully

illustrates episodes from the Mahabbarata.

Bhima is seen worshipping

Ganapati and Duryodhana falls unwillingly at the feet of Krishna who presses

his foot against the earth in order to tumble his throne. Further on the

creeper frieze different scenes from the Ramayana have been carefully

sculptured along with tiny seated musicians: Above the rail there are twenty

pierced stone windows (perforated screens) surmounted by the eaves, ten on the

right and ten on the left of the cast doorway, covering the whole temple. Ten

of them are decorated with Puranic scenes and the rest with geometrical

designs. Among them five on the right and five on the left of the east doorway

are especially noteworthy. On the top panel is Kesava in the centre flanked by

Chauri-bearers, Hanuman and Garuda. Just below this, King Vishnuvardhana, the

founder of this temple, holds a Darbar (royal court). He has a sword in his

right hand and a flower in the left. Mahadevi Shantaladevi, the chief queen is'

seen seated on his left, with her female attendant standing by her side. To his

right, a little in front, two religious teachers (Gurus) are seated with two

disciples behind them. One of them is apparently preaching something to the

king.

Bhima is seen worshipping

Ganapati and Duryodhana falls unwillingly at the feet of Krishna who presses

his foot against the earth in order to tumble his throne. Further on the

creeper frieze different scenes from the Ramayana have been carefully

sculptured along with tiny seated musicians: Above the rail there are twenty

pierced stone windows (perforated screens) surmounted by the eaves, ten on the

right and ten on the left of the cast doorway, covering the whole temple. Ten

of them are decorated with Puranic scenes and the rest with geometrical

designs. Among them five on the right and five on the left of the east doorway

are especially noteworthy. On the top panel is Kesava in the centre flanked by

Chauri-bearers, Hanuman and Garuda. Just below this, King Vishnuvardhana, the

founder of this temple, holds a Darbar (royal court). He has a sword in his

right hand and a flower in the left. Mahadevi Shantaladevi, the chief queen is'

seen seated on his left, with her female attendant standing by her side. To his

right, a little in front, two religious teachers (Gurus) are seated with two

disciples behind them. One of them is apparently preaching something to the

king.

There are also several royal

officers and attendants at his beck and call. The king and queen have many

pieces of jewellery on their persons, especially unusually large earnings. Then

comes a tine scroll and below it a lion with a rider and another standing

vigorously facing the visitors, signifying the vigorous rule of Vishnuvardhana.

The next stone screen depicts

the story of King Bali making a gift to Vamana (Vishnu) and on the top of it

Lakshmi-Narayana are flanked by Hanuman and Garuda. In the middle panel,

Trivikrama (Vishnu) is in the centre with his uplifted foot which is being

carefully washed by Brahma; Bali is seen standing on the right with folded

hands. Garuda stands with folded hands and another drags away Sukracharya, the

preceptor and minister of Bali. On the lower panel Bali's Darbar (royal court)

is open to receive gifts.

At the top of the next panel, Lakshmi-Narayana

are depicted along with their attendants. In the middle panel, Lord Krishna breaks

the pride of the serpent Kaliya (Kaliyadamana) and the lower one depicts a band

of musicians. The next screen re-presents Vishnu flanked by Garuda and Hanuman.

Below this panel, Shiva sits on his bull vehicle Nandi, attended by Garuda and

Kartikeya who in his turn is accompanied by a band of soldiers with flags,

swords, spears and shields. Next to this ten Dikpalakas, including Kubera, are

seen, and the rear panel represents a battle scene.

The next screen illustrates the

story of Prahlada. On the upper panel, Lakshmi-Narayana with Garuda and perhaps

Hanuman can be seen. On the middle panel, Narasimha kills Hiranykashipu

accompanied by Garuda and Hanuman. Just below it Prahlada with folded hands is

meditating on the deity in different poses; he has Tenkala-namam on his

forehead, which is the significant mark of the Vaishnava faith. The Vaishnava

faith and movement became more .active in the South and the perforated screens

were added by Ballala II (A.D. 1173-1220), the grandson of Vishnuvardhana.

We must now discuss the

sculptured beauty of the screens on the left of the eastern doorway. The first

screen is the same as the first on the right. Here, Narasimha I, the son of

Vishnuvardhana, is shown seated in the centre, with his chief queen on his

left. He is in his Durbar (court) and holds a sword in his right hand and a

flower in the left. On their left are three officers with folded hands along

with a group of royal attendants. At the bottom, two lions can be seen. In the

top panel Narasimha is in meditation along with Chauri-bearers, Garuda and Hanuman.

We must now discuss the

sculptured beauty of the screens on the left of the eastern doorway. The first

screen is the same as the first on the right. Here, Narasimha I, the son of

Vishnuvardhana, is shown seated in the centre, with his chief queen on his

left. He is in his Durbar (court) and holds a sword in his right hand and a

flower in the left. On their left are three officers with folded hands along

with a group of royal attendants. At the bottom, two lions can be seen. In the

top panel Narasimha is in meditation along with Chauri-bearers, Garuda and Hanuman.

The fourth screen is rather

interesting; here is the seated figure of Vishnu; the next panel illustrates

the story of the Churning of the Milk Ocean (Samudramanthana). Again, on the

seventh screen, Vishnu is flanked by Garuda and Hanuman. The next panel depicts

the killing of Kamsa by Krishna; and on the next are seen his killing of the

elephant-demon Kuvalayapeda and his contest with the wrestler, Chanura. Again

on the next screen, Lord Krishna is playing on his flute and the cows and wild

beasts, seem enchanted by the magic of his music. The ninth and the tenth screens

are rather interesting; Ranganatha is seen reclining on the beautifully carved

serpent. And' on the last Lakshmi-Narayana is flanked by Chauri-bearers. In the

next screen Hanuman fights with Garuda for the possession of a Linga-like

object. Both of them have placed their hands on it. It is finally split up into

two halves by the discus (Chakra)of Vishnu seated above. In the midst of the

fighting, Hanuman wears the crown of Garuda and vice versa.

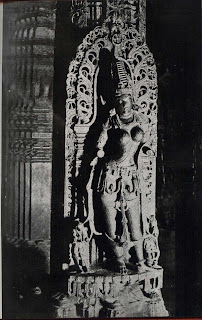

The pillars at the side of

every screen have on their capitals mostly standing female figures supporting

the eaves. They are the masterpieces of Hoysala art. Once there were forty of

them around and inside the temple; two or three are now missing. 'Ili Kannada

they are known as Madanikas. Most of the bracket figures are shown either

lancing or playing on musical instruments or dressing themselves. Two of them represent

Durga and three are huntresses, one carrying a bow and the other shooting birds

with arrows. Some of them are seen with breeches. It is interesting to note hat

on the pedestals of eighteen bracket figures the names of the artists are

inscribed :carefully. These Madanikas are again represented in miniature form

in the sixth frieze of the railed parapet.

As it is traditionally

believed, King Vishnuvardhana married one of the most beautiful of singing and

dancing girls, Shantaladevi, for the second time. She had overwhelming

influence over her royal husband. Under her direction the chief architect Daknacharia,

along with many able craftsmen, beautified the temple with so many Dancing and

singing girls (Madanikas). Further, she had mastery over contemporary ndian

singing and dancing and hence there are so many different Bharat-Natyam poses f

the dancing girls on the walls of the temple. But at Halebid, almost all the

beautiful Madanikas have been removed by human agencies. I have seen many of

these beautiful Sculptures in different museums and private houses of Europe

and America. As a :suit, Halebid temple has lost much of its former glory.

Beyond the railed parapet

(Jagati) there are eighty large images of gods and goddesses of which only

nineteen are female. They are in a continuous row as Halebid, Kedareshvara and

Somnathpur. Among the gods and goddesses are thirty-two images of Vishnu, two

of Lakshmi-Narayana, one of Vamana, two of Narasimha, two of Varaha, one each

of Ranganatha, Balarama, and Hara-Parvati tree of Shiva as the destroyer of

Andhakasura and Gajasura, two of Hari-Hara, four of Surya, five of Durga and

Mahisasuramardini, two of Bhairava, one of Man-matha and Rati, one each of

Ganesha, Brahma, 'Sarasvati, Garuda and Chandra .. .sides these, there are

images of Ravana, Daksha, Arjuna, Bali, and Shukracharya. The large images of

Narasimha on the south-west wall and of Ranganatha on the north-east one add to

the beauty of the temple. The artists, however, did not ignore e basic concept

of life; some small erotic sculptures, can be seen on the outer wall d they do

not mar the beauty of the temple. Moreover, on the third, fifth, and :th

friezes of the railed parapet there are many Hindu divinities.

On the outer walls of the

Garbha-griha (Sanctum). there are three elegantly executed :-like niches on two

storey’s and in three directions. Each storey is decorated with ailed parapet.

On the niches are sculptured friezes of elephants, lions, horsemen, turreted

pilasters and rail with figures, mostly female. On the south niche there is

effigy of Sarasvati with Vishnu below; and on their right wall again Vishnu is

seen 1 a sixteen-armed Narayana seated on a lotus upheld by a four-armed

Garuda. Again, see Vishnu on the west niche and above him, Bhima is seen

fighting against Bhaga-datta's elephant; on the right wall a female devotee

holds a vessel in her left hand and a flower in the right hand. Once again,

Vishnu, Garuda and Sarasvati are sculptured above the devotee. Moreover, on the

left wall on the north niche, a female figure holds two children, apparently

representing Krishna and Balaram. On the right is a female figure and a child

who holds a young lion with rope. He may represent Shakuntala's son Bharata. On

the right wall of the same niche, Durga and her female attendant are seen.

Special attention must be drawn

to some interesting sculptures, for instance, Balarama with a discus (Chakra)

in his left hand and a plough in the right; Chandra holding Kumudas

(water-lilies) in both hands; a sixteen-armed Narasimha slaying Hiranyakashipu;

Kayadhu (Prahlad's mother) and Garuda are artistic and story-telling. Then

there is a Madanika (Kirati) as a huntress to the left of the north doorway

with two small female attendants, one with a bamboo lathi (rod) carrying a dead

deer and a crane apparently shot in the chase. Another small figure is trying

to remove a thorn with the help of a needle from the leg of one of the female

attendants. This is almost a lyrical ballad in stone. Another Madanika in an

amorous mood holds a betel leaf apparently for her lover, while her playful

attendant squirts scented water with a syringe. Other Madanika to the left of

the south entrance is dancing under a creeper canopy. The sculptor has a poetic

vision; on the top near her head are a lizard, a Ely, and a ripe fruit (may be

a jack-fruit); the lizard is preparing to pounce on the fly.

To the right of the north

doorway, on the rail, the king and queen in a relaxed mood are witnessing a

wrestling match and six Shaiva (or Vaishnava) devotees are also shown sitting

nearby in a pensive mood. Just on the left of the same doorway a man with a

long coat, hood and belt is about to cut off his head before a sitting Goddess

(Durga) who at once prevents him from doing so. On the north-east wall, a story

of a chain of destruction is beautifully carved out. A double-headed eagle

attacks a Sarabha (mythical animal) which attacks a lion that in turns attacks

an elephant who is about to destroy a snake that is trying to swallow up a rat

before the ponderous gaze of a mendicant. Similarly, on the right of the north

doorway one Madanika is stripping off her clothes on finding a scorpion in its

fold; the scorpion is again shown on the base. Again, in the fifth frieze to

the left of the south door, a lady is sketching a picture on a board.

At the sides, in front of all

the three entrances, there are two fine pavilions with two more opposite to

them at some distance and on a lower level. Vishnu, Bhairava, and

Mahisasuramardini are on the upper level; and they have a frieze of elephants.

There are likewise three more pavilions on a lower level opposite to the three

car-like niches around the Garbha-griha. They have elephant, lion and horse

friezes on the base and all the nine lower pavilions have both religious and

secular figures. Here, it is important to note that each doorway has at the

sides the Hoysala crest-Sala, the founder of the family, with a sword in hand

ready to kill a lion (or tiger).

The Navaranga (main hall) of

the Chenna Keshava temple appears to have been originally left open as at the

Halebid, Kedaresvara, Somnathpur, and other places, without door-frames and

perforated screens. The door-frames of the Navaranga were added later on, for

the side pillars are mutilated and inscriptions on them arc mostly concealed.

The door-frames, doors, and perforated screens were added to the temple by

Ballala II (1173-1220), the grandson of Vishnuvardhana. The worksmanship is far

superior to that of the outer walls of the temple. The image of Keshava (Vijaya-Narayana)

is a handsome figure of 1.83 metres (six feet) in height with a halo (Prabha),

standing on a 0.91 metre (three feet) high pedestal, with his consort, Iakshmi.

He has four hands; in the upper hands he holds a discus (Chakra) and a conch; a

lotus and a mace are in his lower hands. On the Prabha (halo), the ten

incarnations (Avataras) of Vishnu are represented; the door-keepers

(Dvarapalas) are elegantly executed on the Sukhanasi (vestibule) doorway. Its

pediment with a fine figure of Lakshmi-Narayana in the centre has excellent

filigree work. The Makaras at the side bear Varuna and his consort on the back.

The four pillars were added to the Sukhanasi in A.D. 1381 to support the

dilapidated roof, by the order of the Vijayanagar king Harihara II by his

minister Kampanna.

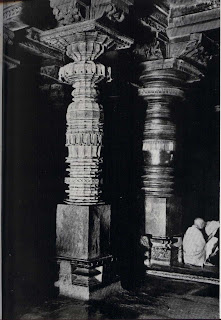

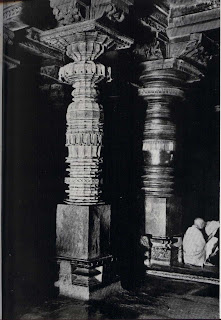

The Navaranga has raised

verandahs on both sides of the three entrances. All the pillars are

artistically executed and are different from one another in design and the

arrangement enhances the beauty of the Navaranga. Sufficient space has been

left out in the central hall (Navaranga) for musical performances and Puja

(worship) ceremonies by large numbers of devotees and others. The well-known

Narsimha pillars are carved out with minute figures all round from the top to

the bottom. A tiny bull (Kadali-basava) is in the size of a seed of the Bengal

gram (Kadal). A small space on the south face of the pillar is said to have

been left blank by the artist who prepared the pillar as a challenge to any

artist who can appropriately fill it up. Another pillar, right of the Sukhanasi

doorway, has the same marvelous filigree work. It is carved with a female

figure in front and has eight vertical bands with fine scroll work the

convolutions of which are made up of delicately executed figures representing

the Hindu minor gods of the eight directions and others. Besides, the lions

with faces of other animals add further to the beauty of the pillar; it is

certainly one of the most beautiful pillars in the whole temple.

The four central pillars support

a large domed ceiling of about 3.05 meters (ten feet) in diameter, 1.83 meters

(six feet) deep. It is a remarkable piece of artistic workmanship famous for

the richness of ornamentation and elaboration of details. Brahma, Vishnu and

Mahesvara are shown on a lotus bud and the bottom frieze of Madanikas, standing

on the capitals of the four central pillars, add much to the grace and charm of

the Navaranga. Three of them are signed by the sculptors. The Tribhanga (triple

bends) pose is really fascinating and a lovely parrot playfully sitting on the

hand. The sculptor is so very skilful that the bracelets moved up and down.

Another Madanika in a dancing pose on the south-east pillar represents

"Dancing Sarasvati". Just to express the ingenuity of the artist,

here head-ornaments can be moved. The third figure on the north-cast pillar is

far more life-like. She has just finished her bath and is carefully dressing

her hair by squeezing out the water from her hair. The last figure on the

north-west pillar is simply dancing before the deity, expressing an exquisite

dramatic pose in stone. Here, the artists have bestowed far greater attention

and care than on the other Madanika. There is no denying the fact that most

magnificent specimens of Hoysala sculpture are the Madanikas. For the sheer

beauty of form, delicacy of worksmanship and perfection of finish, they are

without parallel and may be called "poetry in stone." They have

elicited un-qualified approbation from the art-critics of the world and to the

temple, they have added great grace and charm.

The four central pillars support

a large domed ceiling of about 3.05 meters (ten feet) in diameter, 1.83 meters

(six feet) deep. It is a remarkable piece of artistic workmanship famous for

the richness of ornamentation and elaboration of details. Brahma, Vishnu and

Mahesvara are shown on a lotus bud and the bottom frieze of Madanikas, standing

on the capitals of the four central pillars, add much to the grace and charm of

the Navaranga. Three of them are signed by the sculptors. The Tribhanga (triple

bends) pose is really fascinating and a lovely parrot playfully sitting on the

hand. The sculptor is so very skilful that the bracelets moved up and down.

Another Madanika in a dancing pose on the south-east pillar represents

"Dancing Sarasvati". Just to express the ingenuity of the artist,

here head-ornaments can be moved. The third figure on the north-cast pillar is

far more life-like. She has just finished her bath and is carefully dressing

her hair by squeezing out the water from her hair. The last figure on the

north-west pillar is simply dancing before the deity, expressing an exquisite

dramatic pose in stone. Here, the artists have bestowed far greater attention

and care than on the other Madanika. There is no denying the fact that most

magnificent specimens of Hoysala sculpture are the Madanikas. For the sheer

beauty of form, delicacy of worksmanship and perfection of finish, they are

without parallel and may be called "poetry in stone." They have

elicited un-qualified approbation from the art-critics of the world and to the

temple, they have added great grace and charm.

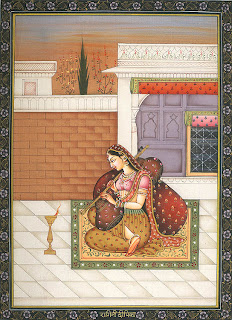

Each one of Madanika figures

here may be taken as a representative illustration of the rhythm and grace of

which an ideal female form is capable. The workmanlike finish given to every

one of them and the remarkable delicacy and skill with which details of

decoration and ornamentation have been executed, have placed on them an

exceptionally high value as pure works of creative art. Moreover, "the

beauty and mirror" is another popular figure of Belur. A dancing girl, on

completing her toilet, looks in the mirror with an air of supreme satisfaction

and fully conscious of her own beauty. She is profusely ornamented. Her broad

forehead, aquiline noze, well-formed lips suggesting a smile, large and almond

shaped eyes with bow-like eyebrows and thick locks of hair tied into a large

knot behind her head, represent the perfection of feminine charm. The slender

waist and round breasts conform to the Indian ideal of feminine beauty.

The graceful curves of the

tribhanga (triple bends) figure add rhythm to her pose. Another favorite theme

of the artist is represented in the two Madanikas with their favorite parrot in

hand; one is teaching her bird and the other is gracefully looking at hers.

They too stand in Tribhangapose displaying the full charm of their well-formed

limbs. Another figure depicts a monkey pulling at the dress of the modest lady.

In her right hand she holds a small branch of a tree with wheel to strike her mischievous

pet. A maiden arranging her coiffure, another with a lyre (Veena), another

singing or beating a tune on a drum, others depicting well-known poses of the

classical dance, another a huntress (Kirati) are the objects that caught the

imagination of Hoysala artist into a matchless performance of technical skill.

The secular nature of the subject matter gave them freedom of action; it

enabled them to modify and even over-look the rigid rules of religious

convention.

The graceful curves of the

tribhanga (triple bends) figure add rhythm to her pose. Another favorite theme

of the artist is represented in the two Madanikas with their favorite parrot in

hand; one is teaching her bird and the other is gracefully looking at hers.

They too stand in Tribhangapose displaying the full charm of their well-formed

limbs. Another figure depicts a monkey pulling at the dress of the modest lady.

In her right hand she holds a small branch of a tree with wheel to strike her mischievous

pet. A maiden arranging her coiffure, another with a lyre (Veena), another

singing or beating a tune on a drum, others depicting well-known poses of the

classical dance, another a huntress (Kirati) are the objects that caught the

imagination of Hoysala artist into a matchless performance of technical skill.

The secular nature of the subject matter gave them freedom of action; it

enabled them to modify and even over-look the rigid rules of religious

convention.

The Hoysala artists, like the

ancient Greek sculptors, took poetic delight in depicting the female form; and

they conceived beauty as an attribute of divinity and employed their skill to

embellish temples. And to them any pretext was sufficient to display their

skill. They displayed a keen sense of realism regarding the human form

especially the female.

The remaining ceiling in the

Navaranga is mostly flat and oblong in shape. In the front of the entrance,

Ashta-Dikpalakas (guardians of the eight directions) are carved out on three

panels; and on the east Narashimha is shown killing Hiranyakashipu. The figure

of Varaha and Keshava are on the southern and northern entrances respectively.

But the ceilings over the verandah show better workmanship of carving; the west

verandah at the south entrance has a frieze depicting stories from the

Ramayana. Moreover, one magnificent Gopuram and an elegant standing Garuda were

subsequently added to enhance the beauty of the temple.

The remaining ceiling in the

Navaranga is mostly flat and oblong in shape. In the front of the entrance,

Ashta-Dikpalakas (guardians of the eight directions) are carved out on three

panels; and on the east Narashimha is shown killing Hiranyakashipu. The figure

of Varaha and Keshava are on the southern and northern entrances respectively.

But the ceilings over the verandah show better workmanship of carving; the west

verandah at the south entrance has a frieze depicting stories from the

Ramayana. Moreover, one magnificent Gopuram and an elegant standing Garuda were

subsequently added to enhance the beauty of the temple.

TECHNICAL

EXPERTS (ARTISTS AND TECHNICIANS)

It may well be presumed that

during the construction period each temple was left under the fostering care of

one master artist-cum-technician who would dictate and guide each and every

part of construction and decoration. It was, of course, assisted by a good

number of able artists to complete the work. It may be that different sections

of the temple were left to the care of a different artist; and thus, they were

able to complete them in a specified period of time. This view was rather

cofirmed when I visited the temples of Belur, Halebid, Kedareshvara,

Somnathpur, and others. Here I should like to refer to a legend current in

Karnataka; it is about the great Jakana-chari and his son Dakanachari.

Jakanachari being suspicious about the fidelity of his wife, secretly left his

home and took service under the Hoysala ruler, Vishnuvardhana.

He was engaged to construct the

Chenna Keshava temple at Belur. After its completion, when the king was about

to install the Mula-Vigraha (main deity), a youth of eighteen years protested

against the proposed installation. He argued that the Mula-Vigraha was unfit to

be installed, since it was a Garbha-shila, i .e., it contained something within

it. To prove his point he was allowed to break the image. To everybody's

surprise, a living frog and a little quantity of sand and water were found

within the image. Thus according to the Shilpa-Shastra the deity could not be

installed. That youth was no other than the son of Jakanachari whose son was

known as Dakanachari. He was much pleased to see his son well-versed in the Shilpa-Shastra

and other religious texts and they both constructed many temples in Karnataka.

Many other well-trained sculptors also assisted them in their work.

He was engaged to construct the

Chenna Keshava temple at Belur. After its completion, when the king was about

to install the Mula-Vigraha (main deity), a youth of eighteen years protested

against the proposed installation. He argued that the Mula-Vigraha was unfit to

be installed, since it was a Garbha-shila, i .e., it contained something within

it. To prove his point he was allowed to break the image. To everybody's

surprise, a living frog and a little quantity of sand and water were found

within the image. Thus according to the Shilpa-Shastra the deity could not be

installed. That youth was no other than the son of Jakanachari whose son was

known as Dakanachari. He was much pleased to see his son well-versed in the Shilpa-Shastra

and other religious texts and they both constructed many temples in Karnataka.

Many other well-trained sculptors also assisted them in their work.

On the pedestals of the

eighteen Madanikas on the outer-walls of the temple and the three inside the

Navaranga and Vishnu on the west wall, the names of the sculptors are

inscribed. I have seen many such in the Halebid, Somnathpur and Kedareshvar

temples. Among the sculptors of the Keshava temple at Belur mention may be made

of Dasoja, his son Chavana, Chikka Hampa, Malliyana, Padari Malloja, Kencha

Malliyanna, Masada and Nagoja. Some of the lebels give details about their

native places, parentage and qualifications.

Balligrame (Belgame) in the

Shikarpur Taluk of the Shimoga district was the native place of Dasoja and his

son Chavana. Dasoja had the title of "smiter of the crowd of titled

sculptors" and his son was a "Shiva to the cupid titled

sculptors". Again, Chavana is said to have "done his work at the

instance of Keshavadeva". Chikka Hampa was the royal artist of

Tribhuvanamalla-Deva and had "prepares some images in the Mandapa (hall)

of Vijaya - Narayana built by Vishnuvardhana." He was the son of Ineja and

had the title of" Champion over rivaj sculptors." Milliyana was the

artist of Maha-Mandaleshvara Tribhuvanamalla and had the title of "a tiger

among sculptors." Again, Padari Malloja had earned the title of "a

pair of large scissors to the necks of titled sculptors." Moreover, Magoja

is claimed to be the artist of god Shvayabhu-Trikuteshvara of Gadugu (Gadag):

one of them had claimed to be the "Vishvakarma of the Kali age." The

names of the sculptors on their artistic creation are a significant departure

from medieval and early modern tradition of India, and the inscribed names have

given us an important clue to the artists of more remote periods.

Balligrame (Belgame) in the

Shikarpur Taluk of the Shimoga district was the native place of Dasoja and his

son Chavana. Dasoja had the title of "smiter of the crowd of titled

sculptors" and his son was a "Shiva to the cupid titled

sculptors". Again, Chavana is said to have "done his work at the

instance of Keshavadeva". Chikka Hampa was the royal artist of

Tribhuvanamalla-Deva and had "prepares some images in the Mandapa (hall)

of Vijaya - Narayana built by Vishnuvardhana." He was the son of Ineja and

had the title of" Champion over rivaj sculptors." Milliyana was the

artist of Maha-Mandaleshvara Tribhuvanamalla and had the title of "a tiger

among sculptors." Again, Padari Malloja had earned the title of "a

pair of large scissors to the necks of titled sculptors." Moreover, Magoja

is claimed to be the artist of god Shvayabhu-Trikuteshvara of Gadugu (Gadag):

one of them had claimed to be the "Vishvakarma of the Kali age." The

names of the sculptors on their artistic creation are a significant departure

from medieval and early modern tradition of India, and the inscribed names have

given us an important clue to the artists of more remote periods.

Now, it is better to sum up the

structural beauty of the temple in James Fergusson's own words. "The

arrangement of the pillars have much of that pleasing subordination and variety

of spacing which is found in those of the Jams, but we miss here the octagonal

dome, which gives such poetry and meaning to the arrangements they adopted. It

is not, however, either to its dimensions or the disposition of its plan, that

this temple owes its pre-eminence among others of its class, but to the

marvellous elaboration and beauty of its details.” And "the amount of

labour, indeed, which each facet of this porch displays is such as, I believe,

never, was bestowed on surface of squal extent in any building in the world; and

though the design is not of the highest order of art, it is elegant and

appropriate and never offends against good taste.”

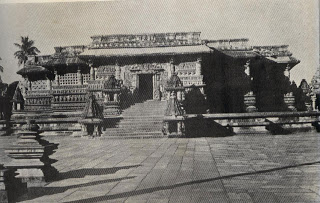

The Halebid village is

(eighteen miles) from Banavar railway station, about 16 kilo-meters (ten miles)

north-east of Belur. It has a direct bus service from Hasan via Belur. In the

ninth century the Rashtrakuta rulers constructed a large lake, called

Dorasamudra, but in the twelveth century the Hoysalas made it their capital

city. Over a century and half they had a large kingdom south of the Krishna

river. In A.D. 1311, Malik Kafur ransacked the city and took "camel-loads

of gold, silver and precious stones" It was pillaged again in A.D. 1326 by

Muhammad-bin-Tughluq. But in its heyday, Dora-samudra was a great city

extending to the south and west of the present village of Halebid.

Round about A.D. 1121

Ketamalla, an officer of Vishnuvardhana, undertook this great work of building

the temple in the name of the king and the queen; and the whole structure was

completed sometime after A.D. 1141. The temple contains two different sanctums,

each with a vestibule. The Navaranga (Central hall) and bull Manda-pa (hall)

and in fact two complete temples are joined by short corridors, both standing

on a common plinth. As at Belur, the sanctum is star-shaped. The Linga in the

south shrine bears the name Vishnuvardhana Hoysaleshvara (or Hoysaleshvara) and

the one in the north has the name of Shantaleshvara'1° two Nandi Mandapas with

two gigantic bulls are on the east. In the later period pierced stone (jali)

windows and doors were attached to the temple.

Round about A.D. 1121

Ketamalla, an officer of Vishnuvardhana, undertook this great work of building

the temple in the name of the king and the queen; and the whole structure was

completed sometime after A.D. 1141. The temple contains two different sanctums,

each with a vestibule. The Navaranga (Central hall) and bull Manda-pa (hall)

and in fact two complete temples are joined by short corridors, both standing

on a common plinth. As at Belur, the sanctum is star-shaped. The Linga in the

south shrine bears the name Vishnuvardhana Hoysaleshvara (or Hoysaleshvara) and

the one in the north has the name of Shantaleshvara'1° two Nandi Mandapas with

two gigantic bulls are on the east. In the later period pierced stone (jali)

windows and doors were attached to the temple.

Among the temples of the Chalukyan style, none

can compare in magnitude, exuberance of carving, and artistic majesty with the

Halebid temple. On its outer walls thousands of figures are sculptured which

gave the artists enough scope for imagination. The temple itself is 48.77 meters

(160 feet) north and south by 37 meters (122 feet) cast and west. From the

basement of the platform the temple is elaborately decorated by horizontal

friezes. The first one represents a march of war elephants, and then between

the two bands of scrollwork is a row of charging horsemen, which is again

followed by episodes from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Bhagavata, and the

Puranas. Just above them are mythical crocodiles (Makaras) with long ornamental

tails, tusks, riders, and a beautiful row of swans (or peacocks).

Among the temples of the Chalukyan style, none

can compare in magnitude, exuberance of carving, and artistic majesty with the

Halebid temple. On its outer walls thousands of figures are sculptured which

gave the artists enough scope for imagination. The temple itself is 48.77 meters

(160 feet) north and south by 37 meters (122 feet) cast and west. From the

basement of the platform the temple is elaborately decorated by horizontal

friezes. The first one represents a march of war elephants, and then between

the two bands of scrollwork is a row of charging horsemen, which is again

followed by episodes from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Bhagavata, and the

Puranas. Just above them are mythical crocodiles (Makaras) with long ornamental

tails, tusks, riders, and a beautiful row of swans (or peacocks).

On the eastern side, just under

the eaves, there were many bracket figures on the pillars; most of them have

now disappeared from there. Consequently, the structural beauty of the temple

has suffered considerably. There is a great deal of controversy among

art-critics regarding spires over the temple. James Fergusson states, "it

was intended to raise two great pyramidal spires over the sanctuaries, four

lower ones in front of these, and two more, as roofs-one over each of the two

central pavilions.”

On the east of the each Linga as mentioned

above, there are two multi-pillared pavilions, side by side with two colossal

bulls which are really majestic in appearance and beautiful in composition. The

bull in the south pavilion is largest and behind it in a small shrine there is

a beautiful standing figure of Surya (Sun-god) with his consorts shooting

arrows, and his car drawn by seven horses. The Nandi-Mandapa is further graced

by beautiful images of Lakshmi-Narayana and a female drummer.

The upper part of the walls have

perforated stone windows on the east side with the images of gods, goddesses,

and Epic and Puranic heroes on the west wall. Most of them are about 0.91

metres (three feet) height, standing or sitting on a pedestal with ornamental

canopies (or arches). They are usually in high relief and thus a great

multitude of Hindu gods and goddesses in different poses and thus have given a

deeper significance to iconographic studies. The majestic figure of Shiva as “Dvarapala

(door-Keeper), Vishnu, Shakti and other deities of the Hindu pantheon arc well

represented. Thus, the outer wall of the Halebid temple may be rightly called a

museum of the Hindu gods and goddesses.

There are five important images

on the north-east wall. It begings with the figure of king Vishnuvardhana or

his officer Kitamalla sitting in his Durbar (Court). In the next panel the gods

and the demons churn the milky ocean for nectar with Vasuki (great mythical

serpent) as the rope, the mount Mandara as the rod supported on the back of

Vishnu as tortoise. Unfortunately, many of the figures are mutilated. One after

another we have the images of Sukracharya with a pot of liquor (Toddy) the

Durbar of Hara and Parvati attended by gods, Joshada and Krishna, Lakshmi-Narayana,

the Ganas and Dikpalas, and king Bali offering the world as a gift to Vishnu

(Vamana), and Chandesh-vara-Shiva. But the east wall is blessed with eleven

images; they are Shiva in his court (Durbar), a fight between Krishna and Indra

for the Parijata tree, Shiva and Vishnu standing close together, and Krishna in

his boyhood.

There are five important images

on the north-east wall. It begings with the figure of king Vishnuvardhana or

his officer Kitamalla sitting in his Durbar (Court). In the next panel the gods

and the demons churn the milky ocean for nectar with Vasuki (great mythical

serpent) as the rope, the mount Mandara as the rod supported on the back of

Vishnu as tortoise. Unfortunately, many of the figures are mutilated. One after

another we have the images of Sukracharya with a pot of liquor (Toddy) the

Durbar of Hara and Parvati attended by gods, Joshada and Krishna, Lakshmi-Narayana,

the Ganas and Dikpalas, and king Bali offering the world as a gift to Vishnu

(Vamana), and Chandesh-vara-Shiva. But the east wall is blessed with eleven

images; they are Shiva in his court (Durbar), a fight between Krishna and Indra

for the Parijata tree, Shiva and Vishnu standing close together, and Krishna in

his boyhood.

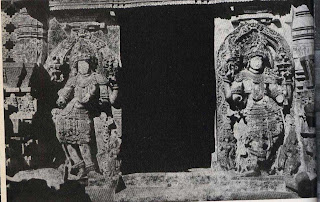

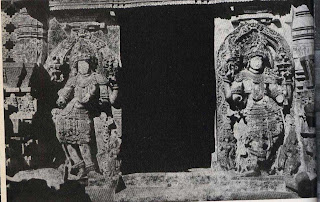

The south-eastern door is

gracefully decorated by six images. Shiva is on the lintel of the doorway and

the arches are fine examples of stone filigree work; the door-keepers are

heavily be-jewelled. Major battles of the Mahabharata war are carefully

depicted and the eighteen days of the conflict can also be identified. Each

warrior hero is shown fighting from his chariot driven by a charioteer. One

panel in the south-cast presents the appointment of aged Bhisma as the

Commander-in-Chief of the Kauravas. And Arjuna's victory over Drona is

celebrated by the soldiers, dancers, and musicians.

On the lintel of the south

door, Shiva is dancing on the body of Andhakasura; his eight hands are more or

less engaged and his beautiful face is beaming with a benign smile after his

victory over the demon. But the fallen demon still looks at him and Nandi. The

dancing god is also accompanied by musicians and drummers and above his head

there is a five-hooded snake with a towering canopy. Brahma and Vishnu are on

his right and left. The arches above are carefully decorated and are supported

on each side by a mythic al Makara with a warrior in its mouth. Varuna (the

Indian Neptune) and his consort are on the Makara's back and are followed by

their attendants. At each end a lion is fighting with an elephant or with Sala,

the progenitor of the Hoysala family. Just above this a group of heavenly

musicians and the guardians of the quarters are assembled. Thus, the whole

complexity of the panels enhances the grace and charm of the south door.

The south-west wall is further

graced by seven images. They are seen dancing Ganesa, Brahma, Karna with his

chariot and standard, Hara-Parvati sitting gracefully terrible Bhairava,

Mohini's nude dance with Bhasmasura, Arjuna shooting an arrow at the eye of a

fish, cowboy Krishna playing on his flute, dancing Sarasvati,

Parijata-Sarasvati, Indra and Indrani on their elephant, Krishna lifting the

Govardhana hill, terrible Bairava, Shiva as the slayer of Gajasura (elephant

demon), Karttikeya (the god of war), Varaha (Vishnu) as the savior of the Earth

goddess, Uma's marriage with Shiva, Durga fighting Mahisasura and Darpana

Sundari.

The south-west wall is further

graced by seven images. They are seen dancing Ganesa, Brahma, Karna with his

chariot and standard, Hara-Parvati sitting gracefully terrible Bhairava,

Mohini's nude dance with Bhasmasura, Arjuna shooting an arrow at the eye of a

fish, cowboy Krishna playing on his flute, dancing Sarasvati,

Parijata-Sarasvati, Indra and Indrani on their elephant, Krishna lifting the

Govardhana hill, terrible Bairava, Shiva as the slayer of Gajasura (elephant

demon), Karttikeya (the god of war), Varaha (Vishnu) as the savior of the Earth

goddess, Uma's marriage with Shiva, Durga fighting Mahisasura and Darpana

Sundari.

The west wall is further

decorated by fifteen images from the Mababharata, Rama-yana and the Puranas.

There are the stories of Prahalad, Narashimha, Manmatha and Rati, Brahma,

battle between Rama and Ravana, vengeance of Draupadi, Vishnu as Trivikrama,

Gajendra Moksha, Parijat-harana, Keshava standing before dancing Lakshmi, Nritya-Sarasvati,

Shiva-Nataraja, Kali, Shiva's war with Arjuna, Rama and the Vali-Sugriva story,

his quest for Sita, and Shakti. Again, the north-west wall is graced by four

Brahmanical images Mohini with a parrot, the killing of Abhimanyu, dancing

Ganesha and the Earth goddess (Bhudevi) and Vasudeva, a dancer, one Gandharva

(heavenly Musician) and a Kaunchuki (eunuch door-keeper of the heavenly harem).

Moreover, the northern wall is similarly decorated with Epic and Puranic images,

such as, Varaha Avatara of Vishnu, Gandharvas, Ravana lifting Mount Kailasa,

Mahisasuramardini, Durga, a Huntress, Gandharva-Kanya and many others.

The square-shaped Navaranga

halls are joined together by a corridor. Among the two the southern part is

better designed, for it contains finer pillars and more elaborately carved

ceilings showing different gods, goddesses and floral motifs. The huge

lathe-turned pillars once supported many bracket figures as at Belur; but most

of them are no longer extant. In the niches stand the beautiful tiny images of

Vishnu, Shiva, Ganesha, Sanmukha, Sarada, Durga, Lakshmi, etc. The canopy and

the tower of the central niche are for more decorative.

The doors of the sanctums and the vestibules

arc of different designs and each door has its own beauty; the door-keepers,

Shiva as Dvarapala, and a chauri-bearer and attend-ants are far more beautiful.

In each sanctum there is a huge pedestal and a large flat-headed Linga placed

by the royal builder and his queen for their religious merit. Although they

were devotees of Vishnu and disciples of Ramanujacharya, they dedicated this

great temple to Lord Shiva.

OTHER

OBJECTS OF INTEREST

In the southern compound of the

temple and near the royal gateway there is a colossal stone image of Ganesha,

and in the north-west corner over a Linga there was formerly a small temple

which is now totally destroyed. Between the main temple and the Linga is a round

pillar with a Kannada inscription recording a tragic story of Hoysal a chivalry.

In olden times, when a Hindu King was crowned, the princes and his body guards

(Garudas) took a terrible oath that they would not live after their royal

master. Thus, when Ballala H died, his bodyguards, headed by prince Lakshmana,

kept their vows and slew themselves. A relief sculpture on the pillar shows

Lakshinana seated like a Yogi waiting to be beheaded, when his followers turned

their daggers and swords upon themselves. Our study of Halebid temple would not

be complete if we do not mention here the words of James Fergusson about the

mythological friezes. "This frieze, which is about 5 to 6 inches in

height, is continued all around the westren front of the building and castends

to some 400 feet in length. Shiva with his consort Parvati seated on his knee,

is repeated at least fourteen times; Vishnu in his various Avataras even

oftener, Brahma occurs several times and every great god of Hindu pantheon

finds his place. Some of these are carved with a minute elaboration of details

which can only be reproduced by photography, and may probably be considered as

one of the most marvellous exhibitions of human labour to be found even in the

patient East....

If the frieze of gods were spread

along a plain surface it would lose more than half its effect, while the

vertical angles, without interfering with the continuity of the frieze, give

height and strength to the whole composition. The disposition of the horizontal

lines of the lower friezes is equally effective. Here again the artistic

combination of horizontal with vertical line and the play of outline and of

light and shade for surpass anything in Gothic art. The effect are just what

the medieval architects were often aiming at, but which they never attained so

perfectly as was done in Halebid.” Again, "No two canopies in the whole

building are alike, and every part exhibits a joyous exuberance of fancy

scorninge very mechanical restraint. All this is wild in human faith or warm in

human feeling is found portrayed on these walls!" Here, again, we have the

names of some of the sculptors, such as Demoja, Kalidasi, Kedaroja and

Talagundura Hari. Unlike Somnathpur, this is a dead temple, for the daily

worship of the deity is not held here. The temple is now looked after by the

Archaeological Survey of India. In the compound of the temple there is an

excellent and a very good library, museum containing some good examples of

Halebid sculpture both of which are quite helpful to scholars; and the Curator

and the Care-taker have done a lot for me.

Somnathpur is a small village

in the Tarumakudalu Narasipur Taluk of the Karnataka district and is situated

about 0.8 kilometre (half a mile) from the Kaveri river. It is about 32

kilometres (twenty miles) from Sirangapatnam. According to epigraphical

records, Somnath (Soma), an officer under Narasimha III (A.D. 1254-1291), built

the Kesava temple in A.D. 1268. The temple is situated in a courtyard measuring

65.53 by 53.95 metres (215 by 177 feet) the main structure is placed on a metre

(three feet) high stone platform. It is a three-celled structure

(Trikutachala), the main cell facing the cast and the other two facing the

north and south; they are surmounted by three elegantly carved towers which are

identical in design and execution.

Somnathpur is a small village

in the Tarumakudalu Narasipur Taluk of the Karnataka district and is situated

about 0.8 kilometre (half a mile) from the Kaveri river. It is about 32

kilometres (twenty miles) from Sirangapatnam. According to epigraphical

records, Somnath (Soma), an officer under Narasimha III (A.D. 1254-1291), built

the Kesava temple in A.D. 1268. The temple is situated in a courtyard measuring

65.53 by 53.95 metres (215 by 177 feet) the main structure is placed on a metre

(three feet) high stone platform. It is a three-celled structure

(Trikutachala), the main cell facing the cast and the other two facing the

north and south; they are surmounted by three elegantly carved towers which are

identical in design and execution.

On both sides of the entrance,

there runs around the front hall a railed parapet (Jagati) and from the bottom

upwards horizontal friezes of elephants, horsemen, scroll - work scenes from

the Epics and the Puranas, turretted pillars, miniature erotic sculpture, and

lions intervening between them, and a rail divided into panels by double columns

with tiny figures, have enhanced the beauty of the temple. Above them are

perforated stone windows (Jali); they are also beautifully decorated with

filigree work and images. From the corners on both sides of the entrance, where

the rail parapet ends, there begins a row of large images with different types

of ornamental canopies. Just below these images there are six horizontal

friezes the first four are identical with the railed parapet design but the

fifth and sixth have a frieze of mythical beasts (Makaras) surmounted by' a row

of swans (or peacocks).

On both sides of the entrance,

there runs around the front hall a railed parapet (Jagati) and from the bottom

upwards horizontal friezes of elephants, horsemen, scroll - work scenes from

the Epics and the Puranas, turretted pillars, miniature erotic sculpture, and

lions intervening between them, and a rail divided into panels by double columns

with tiny figures, have enhanced the beauty of the temple. Above them are

perforated stone windows (Jali); they are also beautifully decorated with

filigree work and images. From the corners on both sides of the entrance, where

the rail parapet ends, there begins a row of large images with different types

of ornamental canopies. Just below these images there are six horizontal

friezes the first four are identical with the railed parapet design but the

fifth and sixth have a frieze of mythical beasts (Makaras) surmounted by' a row

of swans (or peacocks).

We can easily sum up the number

of large images on the walls as one hundred and ninety-four. There are

fifty-four in the south cell; in the corner between the west and north cells

there are only fourteen figures, and there are fifty-four images round the

north cell. The Brahmanical deities represented by the above images are Vishnu

and his different incarnations (i.e., Narasimha, Varaha, Hayagriva, Venugopal

and Parasurama), Brahma, Shiva, Ganapati, Indra-Indrani, Hara-Parvati,

Manmatha, Surya, Garuda, Shakti, Mahishasura-mardini, Karttikeya, Lakshmi,

Sarasvati and a Gandharva. Moreover, apart from the friezes of the Epics and

the Puranas the portions running round the south cell presents scenes from the

Ramayana; the west cell has scenes from the Bhagavata-Purana and the north has

representatives Mahabharata stories.

We can easily sum up the number

of large images on the walls as one hundred and ninety-four. There are

fifty-four in the south cell; in the corner between the west and north cells

there are only fourteen figures, and there are fifty-four images round the

north cell. The Brahmanical deities represented by the above images are Vishnu

and his different incarnations (i.e., Narasimha, Varaha, Hayagriva, Venugopal

and Parasurama), Brahma, Shiva, Ganapati, Indra-Indrani, Hara-Parvati,

Manmatha, Surya, Garuda, Shakti, Mahishasura-mardini, Karttikeya, Lakshmi,

Sarasvati and a Gandharva. Moreover, apart from the friezes of the Epics and

the Puranas the portions running round the south cell presents scenes from the

Ramayana; the west cell has scenes from the Bhagavata-Purana and the north has

representatives Mahabharata stories.

As the temple contains three

cells, each cell consists of a Garbha-griha (Adytum) and a Sukhanasi

(vestibule). On the chief cell (Garbha-griha), just opposite to the main

entrance, there was a Vishnu (Keshava) image about 1 .52 meters (5 feet) high,

but it has been stolen. As a result, it is absolutely a dead temple; nobody

cares to offer puja (worship) here. However, the authorities have replaced the

lost Vishnu image by another of the same size. The temple is now under the

exclusive control of the Archaeological Survey of India.

The north cell has a beautiful

image of Janardana, of about 1.88 meters (6 feet) height, and Venugopala

(Krishna) of the same height breaks the monotony of the southern cell. With a

great amount of ecstasy VenugopaIa is playing his flute before his rapt

listeners, including men and animals. And this panel is really a magnificent

specimen of medieval Indian art. Thus, judging from the figures here the lost

image of Keshava (Krishna) must have been a piece of wonderful worksmanship.

The lintels of both the Garbha-griha and the Sukhanasi doorways of all the

cells are carefully decorated.

The chief cell of the

Garbha-griha doorway depicts a seated figure of Vishnu at the top, an image of

Lakshmi-Narayana in the centre and the ten incarnations of Vishnu at the

bottom. As the base there is a tiny elephant over the Sukhanasi doorway,

Paravasudeva and Keshava are also seen, apparently Vishnu as a Dvarapala

(door-keeper) is on the jambs of both the doorways.

The Navaranga (central hall)

has six ceiling panels and the Mukha-mandapa (front hall) has nine. All of them

are 0.91 meter (three feet) deep and are artistically executed with the

plantain flower (Kadali-Pushpa) design; and formerly difficult colors were

painted on them. Four bell-shaped pillars support the Navaraga and fourteen of

them hold the Mukha-mandapa; they are all artistically-designed.

The Navaranga (central hall)

has six ceiling panels and the Mukha-mandapa (front hall) has nine. All of them

are 0.91 meter (three feet) deep and are artistically executed with the

plantain flower (Kadali-Pushpa) design; and formerly difficult colors were

painted on them. Four bell-shaped pillars support the Navaraga and fourteen of

them hold the Mukha-mandapa; they are all artistically-designed.

Like many other Hoysala

temples, some names of the scupltors are engraved on the pedestals of different

images. They are Mallitamma (Malli), Baleya, Chaudeya, Bamaya, Masanitamma,

Bharmaya, Nanjaya and Yalamasay. Thus, the sculptor Mallitamma played a very significant

role in the decoration of the Keshave temple at Somnathpur. Most probably he

was the artist mainly responsible for the magnificent work to be seen there. In

A.D. 1249, he also worked in the Lakshmi-Narasinha temple at Nuggihalli in the

Channarayapatna Taluk of Hassan district, and we necessarily must attach great

historical value to three temples for their unique contribution to Indian

plastic art. In this connection, we should discuss the role of the legendary

sculptor, Jakanachari, who is believed to have constructed many temples of the

Hoysalas. But no such name has been found in any temple of Karnataka. It may be

a corruption of the Sanskrit word Dashinacharya, that is, a sculptor of the

South school" and perhaps does not denote any particular artist. There is

another possibility that he was the chief architect and sculptor of many

Hoysala temples; and unlike an ordinary artist he did not like to inscribe his

name on them.

There are many temples and

Jain-bastis which were embellished with same amount of skill. Among them

Lakshmidevi, Kappe-Channigarah, Kirtinarayana, Trimurti, Kedareshvara,

Harihara, Someshvara, and many others, are of great artistic value and they

were built during the heyday of the Hoysalas. “Whether we look at these temples

as disinterested historians or art critics or engineers interested in the

details of their structure and beauty, one fundamental truth stands out for all

time, that from faith springs devotion and from devotion the virtues of courage,

patience, sacrifice and intelligence. For otherwise it is hard to explain the

enormous amount of labour and skill that hosts of masons and sculptors poured

for centuries into the construction of these exquisite temples. To modern

generations, they have become a legend. But still many devotees of Hindu

culture who seek inspiration and enlightenment from a knowledge of the past

will not be disappointed by a pilgrimage to these centre’s of ancient art of

Mysore.”

There are many temples and

Jain-bastis which were embellished with same amount of skill. Among them

Lakshmidevi, Kappe-Channigarah, Kirtinarayana, Trimurti, Kedareshvara,

Harihara, Someshvara, and many others, are of great artistic value and they

were built during the heyday of the Hoysalas. “Whether we look at these temples

as disinterested historians or art critics or engineers interested in the

details of their structure and beauty, one fundamental truth stands out for all

time, that from faith springs devotion and from devotion the virtues of courage,

patience, sacrifice and intelligence. For otherwise it is hard to explain the

enormous amount of labour and skill that hosts of masons and sculptors poured

for centuries into the construction of these exquisite temples. To modern

generations, they have become a legend. But still many devotees of Hindu

culture who seek inspiration and enlightenment from a knowledge of the past

will not be disappointed by a pilgrimage to these centre’s of ancient art of

Mysore.”

Writer - S.K. MAITY

Read also -

Bhima is seen worshipping

Ganapati and Duryodhana falls unwillingly at the feet of Krishna who presses

his foot against the earth in order to tumble his throne. Further on the

creeper frieze different scenes from the Ramayana have been carefully

sculptured along with tiny seated musicians: Above the rail there are twenty

pierced stone windows (perforated screens) surmounted by the eaves, ten on the

right and ten on the left of the cast doorway, covering the whole temple. Ten

of them are decorated with Puranic scenes and the rest with geometrical

designs. Among them five on the right and five on the left of the east doorway

are especially noteworthy. On the top panel is Kesava in the centre flanked by

Chauri-bearers, Hanuman and Garuda. Just below this, King Vishnuvardhana, the

founder of this temple, holds a Darbar (royal court). He has a sword in his

right hand and a flower in the left. Mahadevi Shantaladevi, the chief queen is'

seen seated on his left, with her female attendant standing by her side. To his

right, a little in front, two religious teachers (Gurus) are seated with two

disciples behind them. One of them is apparently preaching something to the

king.

Bhima is seen worshipping

Ganapati and Duryodhana falls unwillingly at the feet of Krishna who presses

his foot against the earth in order to tumble his throne. Further on the

creeper frieze different scenes from the Ramayana have been carefully

sculptured along with tiny seated musicians: Above the rail there are twenty

pierced stone windows (perforated screens) surmounted by the eaves, ten on the

right and ten on the left of the cast doorway, covering the whole temple. Ten

of them are decorated with Puranic scenes and the rest with geometrical

designs. Among them five on the right and five on the left of the east doorway

are especially noteworthy. On the top panel is Kesava in the centre flanked by

Chauri-bearers, Hanuman and Garuda. Just below this, King Vishnuvardhana, the

founder of this temple, holds a Darbar (royal court). He has a sword in his

right hand and a flower in the left. Mahadevi Shantaladevi, the chief queen is'

seen seated on his left, with her female attendant standing by her side. To his

right, a little in front, two religious teachers (Gurus) are seated with two

disciples behind them. One of them is apparently preaching something to the

king. We must now discuss the

sculptured beauty of the screens on the left of the eastern doorway. The first

screen is the same as the first on the right. Here, Narasimha I, the son of

Vishnuvardhana, is shown seated in the centre, with his chief queen on his

left. He is in his Durbar (court) and holds a sword in his right hand and a

flower in the left. On their left are three officers with folded hands along

with a group of royal attendants. At the bottom, two lions can be seen. In the

top panel Narasimha is in meditation along with Chauri-bearers, Garuda and Hanuman.

We must now discuss the

sculptured beauty of the screens on the left of the eastern doorway. The first

screen is the same as the first on the right. Here, Narasimha I, the son of

Vishnuvardhana, is shown seated in the centre, with his chief queen on his

left. He is in his Durbar (court) and holds a sword in his right hand and a

flower in the left. On their left are three officers with folded hands along

with a group of royal attendants. At the bottom, two lions can be seen. In the

top panel Narasimha is in meditation along with Chauri-bearers, Garuda and Hanuman.

The four central pillars support

a large domed ceiling of about 3.05 meters (ten feet) in diameter, 1.83 meters

(six feet) deep. It is a remarkable piece of artistic workmanship famous for

the richness of ornamentation and elaboration of details. Brahma, Vishnu and

Mahesvara are shown on a lotus bud and the bottom frieze of Madanikas, standing

on the capitals of the four central pillars, add much to the grace and charm of

the Navaranga. Three of them are signed by the sculptors. The Tribhanga (triple

bends) pose is really fascinating and a lovely parrot playfully sitting on the

hand. The sculptor is so very skilful that the bracelets moved up and down.

Another Madanika in a dancing pose on the south-east pillar represents

"Dancing Sarasvati". Just to express the ingenuity of the artist,

here head-ornaments can be moved. The third figure on the north-cast pillar is

far more life-like. She has just finished her bath and is carefully dressing

her hair by squeezing out the water from her hair. The last figure on the

north-west pillar is simply dancing before the deity, expressing an exquisite

dramatic pose in stone. Here, the artists have bestowed far greater attention

and care than on the other Madanika. There is no denying the fact that most

magnificent specimens of Hoysala sculpture are the Madanikas. For the sheer

beauty of form, delicacy of worksmanship and perfection of finish, they are

without parallel and may be called "poetry in stone." They have

elicited un-qualified approbation from the art-critics of the world and to the

temple, they have added great grace and charm.

The four central pillars support

a large domed ceiling of about 3.05 meters (ten feet) in diameter, 1.83 meters

(six feet) deep. It is a remarkable piece of artistic workmanship famous for

the richness of ornamentation and elaboration of details. Brahma, Vishnu and

Mahesvara are shown on a lotus bud and the bottom frieze of Madanikas, standing

on the capitals of the four central pillars, add much to the grace and charm of

the Navaranga. Three of them are signed by the sculptors. The Tribhanga (triple

bends) pose is really fascinating and a lovely parrot playfully sitting on the

hand. The sculptor is so very skilful that the bracelets moved up and down.

Another Madanika in a dancing pose on the south-east pillar represents

"Dancing Sarasvati". Just to express the ingenuity of the artist,

here head-ornaments can be moved. The third figure on the north-cast pillar is

far more life-like. She has just finished her bath and is carefully dressing

her hair by squeezing out the water from her hair. The last figure on the

north-west pillar is simply dancing before the deity, expressing an exquisite

dramatic pose in stone. Here, the artists have bestowed far greater attention

and care than on the other Madanika. There is no denying the fact that most

magnificent specimens of Hoysala sculpture are the Madanikas. For the sheer

beauty of form, delicacy of worksmanship and perfection of finish, they are

without parallel and may be called "poetry in stone." They have

elicited un-qualified approbation from the art-critics of the world and to the

temple, they have added great grace and charm.  The graceful curves of the

tribhanga (triple bends) figure add rhythm to her pose. Another favorite theme

of the artist is represented in the two Madanikas with their favorite parrot in

hand; one is teaching her bird and the other is gracefully looking at hers.

They too stand in Tribhangapose displaying the full charm of their well-formed

limbs. Another figure depicts a monkey pulling at the dress of the modest lady.

In her right hand she holds a small branch of a tree with wheel to strike her mischievous

pet. A maiden arranging her coiffure, another with a lyre (Veena), another

singing or beating a tune on a drum, others depicting well-known poses of the

classical dance, another a huntress (Kirati) are the objects that caught the

imagination of Hoysala artist into a matchless performance of technical skill.

The secular nature of the subject matter gave them freedom of action; it

enabled them to modify and even over-look the rigid rules of religious

convention.

The graceful curves of the

tribhanga (triple bends) figure add rhythm to her pose. Another favorite theme

of the artist is represented in the two Madanikas with their favorite parrot in

hand; one is teaching her bird and the other is gracefully looking at hers.

They too stand in Tribhangapose displaying the full charm of their well-formed

limbs. Another figure depicts a monkey pulling at the dress of the modest lady.

In her right hand she holds a small branch of a tree with wheel to strike her mischievous

pet. A maiden arranging her coiffure, another with a lyre (Veena), another

singing or beating a tune on a drum, others depicting well-known poses of the

classical dance, another a huntress (Kirati) are the objects that caught the

imagination of Hoysala artist into a matchless performance of technical skill.

The secular nature of the subject matter gave them freedom of action; it

enabled them to modify and even over-look the rigid rules of religious

convention.  The remaining ceiling in the

Navaranga is mostly flat and oblong in shape. In the front of the entrance,

Ashta-Dikpalakas (guardians of the eight directions) are carved out on three

panels; and on the east Narashimha is shown killing Hiranyakashipu. The figure

of Varaha and Keshava are on the southern and northern entrances respectively.

But the ceilings over the verandah show better workmanship of carving; the west

verandah at the south entrance has a frieze depicting stories from the

Ramayana. Moreover, one magnificent Gopuram and an elegant standing Garuda were

subsequently added to enhance the beauty of the temple.

The remaining ceiling in the

Navaranga is mostly flat and oblong in shape. In the front of the entrance,

Ashta-Dikpalakas (guardians of the eight directions) are carved out on three

panels; and on the east Narashimha is shown killing Hiranyakashipu. The figure

of Varaha and Keshava are on the southern and northern entrances respectively.

But the ceilings over the verandah show better workmanship of carving; the west

verandah at the south entrance has a frieze depicting stories from the

Ramayana. Moreover, one magnificent Gopuram and an elegant standing Garuda were

subsequently added to enhance the beauty of the temple. He was engaged to construct the

Chenna Keshava temple at Belur. After its completion, when the king was about

to install the Mula-Vigraha (main deity), a youth of eighteen years protested

against the proposed installation. He argued that the Mula-Vigraha was unfit to

be installed, since it was a Garbha-shila, i .e., it contained something within

it. To prove his point he was allowed to break the image. To everybody's

surprise, a living frog and a little quantity of sand and water were found

within the image. Thus according to the Shilpa-Shastra the deity could not be

installed. That youth was no other than the son of Jakanachari whose son was

known as Dakanachari. He was much pleased to see his son well-versed in the Shilpa-Shastra

and other religious texts and they both constructed many temples in Karnataka.

Many other well-trained sculptors also assisted them in their work.

He was engaged to construct the

Chenna Keshava temple at Belur. After its completion, when the king was about

to install the Mula-Vigraha (main deity), a youth of eighteen years protested

against the proposed installation. He argued that the Mula-Vigraha was unfit to

be installed, since it was a Garbha-shila, i .e., it contained something within

it. To prove his point he was allowed to break the image. To everybody's

surprise, a living frog and a little quantity of sand and water were found

within the image. Thus according to the Shilpa-Shastra the deity could not be

installed. That youth was no other than the son of Jakanachari whose son was

known as Dakanachari. He was much pleased to see his son well-versed in the Shilpa-Shastra

and other religious texts and they both constructed many temples in Karnataka.

Many other well-trained sculptors also assisted them in their work.  Balligrame (Belgame) in the

Shikarpur Taluk of the Shimoga district was the native place of Dasoja and his

son Chavana. Dasoja had the title of "smiter of the crowd of titled

sculptors" and his son was a "Shiva to the cupid titled

sculptors". Again, Chavana is said to have "done his work at the

instance of Keshavadeva". Chikka Hampa was the royal artist of

Tribhuvanamalla-Deva and had "prepares some images in the Mandapa (hall)

of Vijaya - Narayana built by Vishnuvardhana." He was the son of Ineja and

had the title of" Champion over rivaj sculptors." Milliyana was the

artist of Maha-Mandaleshvara Tribhuvanamalla and had the title of "a tiger

among sculptors." Again, Padari Malloja had earned the title of "a

pair of large scissors to the necks of titled sculptors." Moreover, Magoja

is claimed to be the artist of god Shvayabhu-Trikuteshvara of Gadugu (Gadag):

one of them had claimed to be the "Vishvakarma of the Kali age." The

names of the sculptors on their artistic creation are a significant departure

from medieval and early modern tradition of India, and the inscribed names have

given us an important clue to the artists of more remote periods.

Balligrame (Belgame) in the

Shikarpur Taluk of the Shimoga district was the native place of Dasoja and his

son Chavana. Dasoja had the title of "smiter of the crowd of titled

sculptors" and his son was a "Shiva to the cupid titled

sculptors". Again, Chavana is said to have "done his work at the

instance of Keshavadeva". Chikka Hampa was the royal artist of

Tribhuvanamalla-Deva and had "prepares some images in the Mandapa (hall)

of Vijaya - Narayana built by Vishnuvardhana." He was the son of Ineja and

had the title of" Champion over rivaj sculptors." Milliyana was the

artist of Maha-Mandaleshvara Tribhuvanamalla and had the title of "a tiger

among sculptors." Again, Padari Malloja had earned the title of "a

pair of large scissors to the necks of titled sculptors." Moreover, Magoja

is claimed to be the artist of god Shvayabhu-Trikuteshvara of Gadugu (Gadag):

one of them had claimed to be the "Vishvakarma of the Kali age." The

names of the sculptors on their artistic creation are a significant departure

from medieval and early modern tradition of India, and the inscribed names have

given us an important clue to the artists of more remote periods.  Round about A.D. 1121

Ketamalla, an officer of Vishnuvardhana, undertook this great work of building

the temple in the name of the king and the queen; and the whole structure was

completed sometime after A.D. 1141. The temple contains two different sanctums,

each with a vestibule. The Navaranga (Central hall) and bull Manda-pa (hall)

and in fact two complete temples are joined by short corridors, both standing

on a common plinth. As at Belur, the sanctum is star-shaped. The Linga in the

south shrine bears the name Vishnuvardhana Hoysaleshvara (or Hoysaleshvara) and

the one in the north has the name of Shantaleshvara'1° two Nandi Mandapas with

two gigantic bulls are on the east. In the later period pierced stone (jali)

windows and doors were attached to the temple.

Round about A.D. 1121