To

understand any great art, one has to view it as an organism with its own soul,

forms of expression and conventions. Art is the symbol of the culture to which

it belongs, acquiring its style of expression in relation to it. Every culture

has thus its own style of art, and one must know the culture to understand its

phases of development. This is also true of Kangra art.

All

great art is inspired by religion. The paintings and sculpture of Ajanta and

the great monument of Borobudur in Java we their origin to the inspiration of

Buddhism. Christianity inspired paintings of sublime quality in medieval Italy

and Spain. The Hindu painting of Rajasthan and the Punjab hills, known as

Rajput painting, because the patrons were Rajput princes, was inspired by the Vaishnava

faith.

The 11th

century witnessed the rise of Vaishnavism as the creed of the Hindus. In the

field of literature, Prakrits and later regional languages replaced Sanskrit.

The heralds of the dawn were Ramanuja and Jayadeva. Ramanuja (A.D. 1017-1137)

was born in the village of Sriperumbudur, south-east of Kancheepuram in Tamil

Nadu. He mastered the Vedas and the sacred books, and wrote commentaries on the

Vedanta, the Sutras, and the Bhagavad-Gita. As a pilgrim he travelled widely

over India, visiting Jagannath, Kasi, Badrinath in the Himalayas, and other

places. His earthly journey came to an end at Sriranganatha in A.D. 1137.

Ramanuja

popularised the worship of Vishnu as the Supreme Being and Creator of all

things. According to Vaishnava doctrine, Vishnu pervades all creation, Lakshmi

supplying His energy. When sins multiply, He becomes incarnate to rid the earth

of its burden. The followers of Ramanuja venerate (iligreima, the ammonite

stone, and the tulasi plant as symbols of Vishnu and Lakshmi.

Jayadeva

was born at Kenduli in the district of Birbhum, West Bengal, and in course of

time became one of the five court poets of Raja Lakshmana Sen, who ruled Bengal

about A.D. 1170. In his early years he was a wandering ascetic. In the course

of his travels, he visited the holy shrine of Jagannath and there a strange

event changed the course of his life. Padmavati, a beautiful Brahmin girl, was

to be dedicated as a temple-girl to Lord Jagannath, but it is said that the

image ordered her father to bestow the girl upon the saint Jayadeva. Much

against his wishes, Jayadeva accepted her, and she attended on him like his

shadow. Inspired by her beauty, he composed the immortal poem, Gita Govinda,

the Song of the Divine Cowherd, in which he describes the love of Krishna and

Radha. The poem won wide popularity and is still chanted in Bengal and the

Karnatak.

The

Gita Govinda is a symbolical love song based on the poet's spiritual

experience. Krishna is the human soul attached to earthly pleasures and Radha,

the heroine, is Divine Wisdom. The milkmaids who tempt Krishna from Radha are

the five senses of smell, sight, touch, taste and hearing, and the return of

Krishna to Radha, his first love, is regarded as the return of the repentant

sinner to God.

Ramanand,

born at Melkot in A.D. 1398, was another great religious teacher. He settled at

Varanasi, where he attracted a large number of devotees. He popularised the

worship of Rama and Sita as incarnations of Vishnu and Lakshmi.

Another

factor which promoted Vaishnavism was the emergence of Islam. From the 12th

century onwards India was ravaged by Islamic hordes from the north. The

monotheism of Islam and particularly the cult of Sufism had an influence on the

Hindu religious thought which was already showing dissatisfaction with cold

intellectualism, sterile philosophies and arid speculations of Buddhism. Islam

declared that One Great God was the supporter of the world and helped the

virtuous. The Hindu masses also keenly felt the spiritual need of a loving personal

God. Thus developed the Krishna cult.

Another

factor which promoted Vaishnavism was the emergence of Islam. From the 12th

century onwards India was ravaged by Islamic hordes from the north. The

monotheism of Islam and particularly the cult of Sufism had an influence on the

Hindu religious thought which was already showing dissatisfaction with cold

intellectualism, sterile philosophies and arid speculations of Buddhism. Islam

declared that One Great God was the supporter of the world and helped the

virtuous. The Hindu masses also keenly felt the spiritual need of a loving personal

God. Thus developed the Krishna cult.

Kabir

(A.D. 1398-1516) was a disciple of Ramanand. This great mystic denounced the

pretences both of the Brahmin priests and Muslim mullcis of Banaras, but had

followers both among the Hindus and the Muslims. His writings, which form the

cornerstone of Hindi literature, were compiled by a certain Dharam Das. Dharam

Das and his son, Kamal, are often shown with Kabir in Kangra paintings.

It was

Eastern India, the provinces of Bihar and Bengal, which became the home of the

Radha-Krishna cult. Vidyapati (fl.A.D. 1400-70), the poet of Bihar, wrote in

the Maithili dialect on the Radha and Krishna theme. He was the most famous of

the Vaishnava poets of Eastern India. He was inspired by the beauty of Lacchima

Devi, queen of his great patron, Raja Sib Singh. Sib Singh was summoned by

Akbar to Delhi for some offence, and Vidyapati obtained his patron's release by

an exhibition of clairvoyance. The incident is thus described by Grierson.

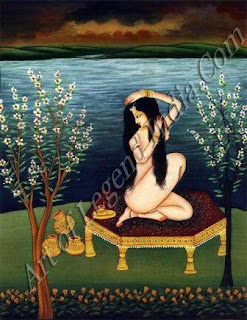

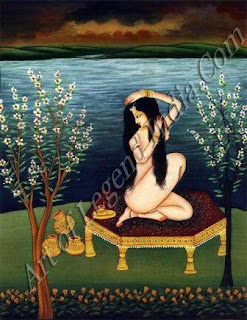

"The emperor locked him up in a wooden box, and sent a number of

courtesans of the town to bathe in the river. When all was over he released him

and asked him to describe what had occurred, when Vidyapati immediately recited

impromptu one of the most charming of his sonnets, which has come down to us,

describing a beautiful girl at her bath. Astonished at his power, the emperor

granted his petition to release Sib Singh."' In the love-sonnets of the

great master-singer of Mithila we find sacredness wedded to sensuous joy. There

are vivid word-pictures of the love of Radha and Krishna painted in musical

language. Coming direct from the heart they remind us that there is nothing so

beautiful and touching as simplicity.

A

contemporary of Vidyapati was Chandi Das (fl.A.D. 1420) who lived at Nannur in

Birbhum district of West Bengal. "Representing the glow and ardour of

impassioned love", says Dinesh Chandra Sen, "he became the harbinger

of a new age which soon after dawned on our moral and spiritual life and

charged it with the white heat of its emotional bliss." Chandi Das had

fallen in love with a washer-woman, Rami by name, and in describing the

physical charm of the heroine of his poetry he was drawing upon his own

experience. In the poems of Chandi Das, sensuous emotions are sublimated into

spiritual delight and the pleasures of the senses find an outlet in mystic

ecstasy.

Chaitanya

(A.D. 1486-1533) was the prophet of Vaishnavism in Bengal. Nimai, as his

original name was, belonged to a Brahmin family of Nadia. While still a young

man he felt the urge for renunciation of worldly ties and left his home and

young wife. He reached Puri, and Prataparudradeva, the Raja of Orissa, became

his disciple. From there he wandered into South India where he discoursed to

people in Tamil. Far more impressive than his discourses were his mystic

trances. Tears flowed from his eyes, and as he lay on the ground the very sight

of him sanctified men. Scholars groaning under the weight of learning and

philosophers weary of old and heartless intellectualism felt humble in his

presence and experienced a strange emotion which cured the sickness of the

soul. Here was a teacher who was not teaching intricate philosophies, but the

strange power of love, which they could themselves experience. This emotional

religion, which believed in sensitising of emotions and sublimating them,

rejected reasoning and subtleties of the intellect. His life was a living poem,

and his spiritual force had a mesmerising effect on the people. The very sight

of the dark-blue clouds, the ocean or the river re-minded him of his God,

Krishna, and he fell into a trance. As Dinesh Chandra Sen describes: "He

fainted at the sight of the lightning which he mistook for the bright purple

robe of the Lord. The chirp of the birds was continually mistaken for the sound

of the flute, and he thought that Some One called him to his embrace by the

sweet music. The cranes flew in the dark-blue sky in flocks looking small from

a distance and Chaitanya thought them to be a string of pearls decorating the

breast of his dark-blue God. At the sight of every hillock he fell into a

trance, reminded of the Govardhan hills where Krishna had sported, and every

river showed him the ripples of the Yamuna on the banks of which the pastoral

Ciod had played with his fellow cowherdu. 'I he nowert: reminded 1iiiiof the

braid of the Krishna's eyes and he wept when he touched them, reminded of the

Divine touch, soft and sweet. Miami Mien I he smell Of tloweru emanating from

the Puri temple kept him tied to the spot like a MOM; he thought that his

Krishna was approaching and the seent of a thousand flowers announced his

approach, and he trembled in deep emotion with tearful eyes and passed into a

trance."

The

religious revival also stimulated literary activity. The cults of Rama and

Sita, Krishna and Radha were the source of inspiration to many poets who wrote

in Sanskrit and Hindi. Jayadeva, Ramanand and Kabir are among the most

prominent. Malik Muhammad Jayasi completed Pachmivat, his well-known romance,

in A.D. 1540 and Keshav Das, the court poet of Indrajit Shah of Orchha, wrote

his famous love poem Rasikapriyd in A.D. 1591. Tulsi Das, one of the greatest

of Hindi poets, was born in A.D. 1532. His Rdmayana is the most popular book in

the villages of Avadh, and it is the basis of the moral and religious life of

millions of people.

Bihari

Lal, who lived in Mathura, the home of the Braj-Bhasa dialect, completed his

Sat Sal, or 700 couplets on the Krishna legend, in A.D. 1662. These little

poems are gems of Hindi literature and have won much fame for their author.

In the

16th and 17th centuries, the way was thus being prepared

for the emergence of a new form of art born of the rapidly spreading Vaishnava

cult in which spiritual experience was symbolised by the relations of the Lover

and the Beloved.

In this

art the worlds of spiritual purity and sensuous delight are interwoven,

religion and aesthetics moving hand in hand in quest of Reality. The Gita

Govinda and the Rameiyana have been illustrated both in the Basoldi and Kangra

styles. Padmavati, whose story is sung by Jayasi, is the subject of a number of

paintings. The eight Ardyikais and Bcircimeisti are favourite themes alike with

Kangra painters and the Hindi poets Keshav Das, Matiram, Bansidhar, Ramguni and

Gang, and numerous paintings which illustrate their works are extant. Another

important source of inspiration to the Kangra artists is the culture of the

Punjab.

This source has not been adequately considered by art critics, who

usually have little knowledge of the province, its people and culture. In

Kangra paintings, particularly those of Nurpur and Guler, which' were close to

the plains, the dress of the women is typically Punjabi; they are usually shown

as wearing suthhatz that resembles breeches, kamiz, and dupaltd. The popular

love tales of the Punjab Hir Ranjha, Mirza-Sahiban and Sohni-Mahinwal are often

illustrated by the Kangra artists. Reference may now be made to the great Sikh

movement in the plains of the Punjab. Nanak (A.D. 1469-1538), the first Sikh

Guru, freed the Punjabi mind from superstition and ritualism, and called upon

people to break through the barriers of institutionalised priestly religion.

Guru Nanak made extensive use of the local language, and Angad, his successor,

devised the Punjabi alphabet, based mainly on Takri. Arjan (A.D. 1581-1606),

the fifth Guru, compiled the Guru Granth, in which he incorporated Nanak's

Japji, as well as the religious poetry of Kabir, Jayadeva, Namdev, Dhanna,

Pipa, the Gurus Amar Das and Ram Das and other bhaktas.

Gobind

Singh (A.D. 1675-1708), the tenth Guru, chose Anandpur, a village at the

foothills of the Shivaliks for his residence. He was a champion of the

downtrodden and constantly fought the Mughal armies and the Hill Chiefs from

Anandpur on the Sutlej to Paunta on the Yamuna. He was not only a soldier, but

a poet and a scholar well versed in Persian, Hindi and Sanskrit.

He

translated the legends of Rama and Krishna. His Chodi-ki-weir, which deals with

the exploits of Durga, is written in powerful language. Besides being a poet

himself, the Guru kept fifty-two bards permanently in his employ. Their

compositions, which must have been considerable, were lost during the wars

against the Mughal Emperor and the Hill Chiefs.

He

translated the legends of Rama and Krishna. His Chodi-ki-weir, which deals with

the exploits of Durga, is written in powerful language. Besides being a poet

himself, the Guru kept fifty-two bards permanently in his employ. Their

compositions, which must have been considerable, were lost during the wars

against the Mughal Emperor and the Hill Chiefs.

The ten

Sikh Gurus have been painted by the court artists of Guler and Kangra. From

1810 the Kangra Valley was under the rule of the great Ranjit Singh, and Sikh

influence is apparent in Kangra paintings of this period. From 1830 onwards, we

find long flowing beards and splendid turbans instead of beards trimmed in the

Muslim style.

Thus,

Karigra art is the visual expression of a cultural movement with roots in a

great spiritual upsurge. Kangra painting is not a sudden development unrelated

to the life of Northern India, but is the culmination of a spiritual and

literary revival of Hinduism. Dr. Coomaraswamy rightly observes that

"these works are an immediate expression of the Hindu view of life. Here

is that distinct, sharp and wiry bounding line which Blake, most Indian of

modern Western minds, regarded as the golden rule of art and life. A line so deliberate,

so self-confident, so full of wonder at the beauty of the world, especially the

beauty of women, and at the same time so austere, could not be a sudden

achievement, nor depend on the brilliance of a single personality. It is the

product of a whole civilization."

Writer – M.S. Randhawa

Another

factor which promoted Vaishnavism was the emergence of Islam. From the 12th

century onwards India was ravaged by Islamic hordes from the north. The

monotheism of Islam and particularly the cult of Sufism had an influence on the

Hindu religious thought which was already showing dissatisfaction with cold

intellectualism, sterile philosophies and arid speculations of Buddhism. Islam

declared that One Great God was the supporter of the world and helped the

virtuous. The Hindu masses also keenly felt the spiritual need of a loving personal

God. Thus developed the Krishna cult.

Another

factor which promoted Vaishnavism was the emergence of Islam. From the 12th

century onwards India was ravaged by Islamic hordes from the north. The

monotheism of Islam and particularly the cult of Sufism had an influence on the

Hindu religious thought which was already showing dissatisfaction with cold

intellectualism, sterile philosophies and arid speculations of Buddhism. Islam

declared that One Great God was the supporter of the world and helped the

virtuous. The Hindu masses also keenly felt the spiritual need of a loving personal

God. Thus developed the Krishna cult.  He

translated the legends of Rama and Krishna. His Chodi-ki-weir, which deals with

the exploits of Durga, is written in powerful language. Besides being a poet

himself, the Guru kept fifty-two bards permanently in his employ. Their

compositions, which must have been considerable, were lost during the wars

against the Mughal Emperor and the Hill Chiefs.

He

translated the legends of Rama and Krishna. His Chodi-ki-weir, which deals with

the exploits of Durga, is written in powerful language. Besides being a poet

himself, the Guru kept fifty-two bards permanently in his employ. Their

compositions, which must have been considerable, were lost during the wars

against the Mughal Emperor and the Hill Chiefs.

0 Response to "The Cultural Background "

Post a Comment