To

understand this school in its proper perspective, the traditions in which it

has its roots should be considered. The source of Mughal painting was Persian.

The art of Persia was greatly influenced by Mongolian art. The art of Central

Asia is almost reflected in pre-Timurid and Timurid art. It is this blend of

the art of Chinese Turkistan and Persia that travelled to India and in ideal

surroundings softened and mellowed, acquired the best elements of the

indigenous traditions in the country and flowered into a great and noble art,

which has its own distinctive character not only as a great court art but also

as a distinct development closely associated with the land where it blossomed.

Mughal

painting is distinctive but Indian. It has the flavour of the Persian but the

inborn charm of Indian tradition. Babar, the fifth descendant from Timur, was

aware of the great and remarkable ability of Bihzad, the famous artist of his

time; but engaged as he was in the establishment of his kingdom, having proved

unsuccessful in his attempt at securing Kandahar, the old capital of his

ancestors, and turning his eyes from Kabul to India to secure at least an

eastern expansion from his little rocky kingdom, he could not devote that

attention to art which his son Humayun could. That painting flourished in his

time is clearly seen from the Alwar manuscript of the Persian version of his

Memoirs where the illustrations show the style of painting during his day.

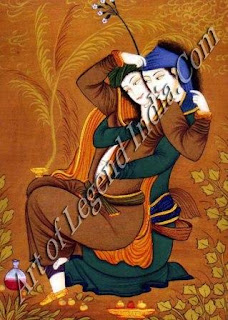

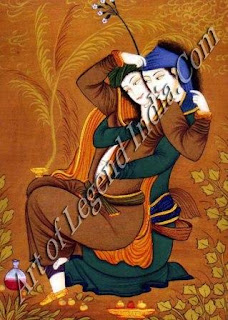

Humayun's

misfortunes drove him to Persia as an exile and Sher Shah's triumph saw Humayun

looking for refuge with Shah Tahmasp of Persia. This was indeed a godsend for

the artistic inclination of Humayun, as the Shah was a great patron of art, and

among his court painters were Bihzad, Mirak and others.

Humayun's

misfortunes drove him to Persia as an exile and Sher Shah's triumph saw Humayun

looking for refuge with Shah Tahmasp of Persia. This was indeed a godsend for

the artistic inclination of Humayun, as the Shah was a great patron of art, and

among his court painters were Bihzad, Mirak and others.

Akbar,

who was very young when he succeeded his father, was an illiterate but

possessed a rare flair for appreciation of learning and art, and probably was

more alert with his ears and eyes than any scholar or connoisseur of his time.

He had an enormous passion for learning and built up a marvellous library of

Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit books. He had the famous books from these

languages translated into others and learnt by listening more than by studies.

Having been himself an artist in his youth, Akbar zealously patronised art and

held the view that the artist who drew with accuracy could only realise the

superiority of the Creator who could even infuse life into the objects that the

artist could just draw so faithfully. Akbar was equally at home in all the fine

arts, and painting flourished at his court. The Akbar Nama, the Razm Nona and

other works were profusely illustrated at his command. The Persian artists who

flocked to his court taught the new technique to the Indian artists and

themselves benefited by absorbing the best elements of indigenous traditions,

with the result that a rare blend of a wonderful new school came into

existence. The names of Manohar, Farukchela, Basawan and Madhu, to mention a

few, were famous during Akbar's days.

The

story of Mughal painting in India may be said to have begun with Khwaja Abdus

Samad of Shiraz who was patronised by Humayun and continued in the time of

Akbar. Daswant, the poor son of a palanquin-bearer whom the emperor Akbar

discovered and apprenticed to Abdus Samad, is a symbol of other Hindu artists

who practised the Persian way and created a new efflorescence of art. Another

great name at Akbar's court amongst the Hindu masters is Basawan. The practice

of signing pictures in this period of art history gives us names of artists at

Akbar's court of which a large number is given in the Ain-e-Akbari like Mukund,

Madhu, Khemkaran, Harbans, Kesavlal and others. The illustrated Babar Nama,

Akbar Nama, Hamza Nama, Razm Nama and other beautifully illustrated manuscripts

of the period are a great artistic achievement. Still in this period, the

Persian treatment of the background and the landscape is obvious, though slowly

this influence, diminishes in the successive periods. The building of Fatehpur

Sikri, the emperor's chase of wild animals and, particularly, the birth of his

second son Murad at Fatehpur Sikri are splendid illustrations in which the

Akbar Nama abounds.

The

story of Mughal painting in India may be said to have begun with Khwaja Abdus

Samad of Shiraz who was patronised by Humayun and continued in the time of

Akbar. Daswant, the poor son of a palanquin-bearer whom the emperor Akbar

discovered and apprenticed to Abdus Samad, is a symbol of other Hindu artists

who practised the Persian way and created a new efflorescence of art. Another

great name at Akbar's court amongst the Hindu masters is Basawan. The practice

of signing pictures in this period of art history gives us names of artists at

Akbar's court of which a large number is given in the Ain-e-Akbari like Mukund,

Madhu, Khemkaran, Harbans, Kesavlal and others. The illustrated Babar Nama,

Akbar Nama, Hamza Nama, Razm Nama and other beautifully illustrated manuscripts

of the period are a great artistic achievement. Still in this period, the

Persian treatment of the background and the landscape is obvious, though slowly

this influence, diminishes in the successive periods. The building of Fatehpur

Sikri, the emperor's chase of wild animals and, particularly, the birth of his

second son Murad at Fatehpur Sikri are splendid illustrations in which the

Akbar Nama abounds.

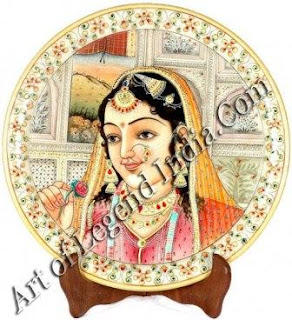

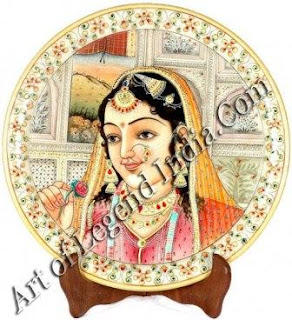

Jehangir,

who had an intelligent wife to manage state-craft, was left with sufficient

leisure to enjoy wine and appreciate art. Probably this was the greatest period

of the renaissance of Mughal art. He was a great patron and maintained a bevy

of painters at his court. In his Memoirs he prides himself on his

connoisseurship, how he could discriminate the work of one artist from that of

another and single out the painting of any individual artist even to the point

of distinguishing any touches added by a subsequent painter on an original by

another. The emperor delighted in beautiful portraits of his and had groups painted

of himself, his lovely queen and his family. Some of the most beautiful animal

and flower patterns were drawn and painted during his day. Portraiture was so

developed that there was a great element of realism during Jehangir's reign.

Mansur and Bishandas amongst several others ranked as very famous painters of

his day. Sir Thomas Roe has left anecdotes throwing light on the emperor's keen

enthusiasm in portrait-painting. It is no wonder that the admirable portraits

of this period evoked the appreciation of the great British painter, Sir Joshua

Reynolds.

Jehangir's

son Shah Jahan was, though a connoisseur, more a builder of great monuments and

a pattern of architecture. Painting flourished, no doubt, during his day, but

its heyday was reached during the time of his father. The puritan Aurangzeb,

who imprisoned his father Shah Jahan and came to the throne, could not probably

provide encouragement to the art that he considered against the tenets of his

religion, and the disappointed artists of the Mughal court had slowly to find a

better atmosphere for survival elsewhere. Thus from this time onwards not only

music was buried deep but art also was driven away to different homes and the

provincial schools in Amritsar, Lahore, Lucknow, Oudh, Murshidabad, Golconda,

and other places absorbed the painters of the Moghal court who were driven to

seek a home elsewhere.

Jehangir's

son Shah Jahan was, though a connoisseur, more a builder of great monuments and

a pattern of architecture. Painting flourished, no doubt, during his day, but

its heyday was reached during the time of his father. The puritan Aurangzeb,

who imprisoned his father Shah Jahan and came to the throne, could not probably

provide encouragement to the art that he considered against the tenets of his

religion, and the disappointed artists of the Mughal court had slowly to find a

better atmosphere for survival elsewhere. Thus from this time onwards not only

music was buried deep but art also was driven away to different homes and the

provincial schools in Amritsar, Lahore, Lucknow, Oudh, Murshidabad, Golconda,

and other places absorbed the painters of the Moghal court who were driven to

seek a home elsewhere.

Mughal

art, which started as an art of illustration and excelled in portraiture in the

succeeding period, which was the best, became at last a rather weak expression

of life around in pictorial terms. Starting with a strong Persian bias, it

slowly assimilated a blend of the indigenous with an efflorescence in which the

foreign flavour was finally eliminated almost completely.

No

description of Mughal painting would be complete without a reference to the

delicate treatment of birds, animals and plants which rank among some of the

greatest masterpieces of this period.

Writer

– C.Sivaramamurti

Humayun's

misfortunes drove him to Persia as an exile and Sher Shah's triumph saw Humayun

looking for refuge with Shah Tahmasp of Persia. This was indeed a godsend for

the artistic inclination of Humayun, as the Shah was a great patron of art, and

among his court painters were Bihzad, Mirak and others.

Humayun's

misfortunes drove him to Persia as an exile and Sher Shah's triumph saw Humayun

looking for refuge with Shah Tahmasp of Persia. This was indeed a godsend for

the artistic inclination of Humayun, as the Shah was a great patron of art, and

among his court painters were Bihzad, Mirak and others.  The

story of Mughal painting in India may be said to have begun with Khwaja Abdus

Samad of Shiraz who was patronised by Humayun and continued in the time of

Akbar. Daswant, the poor son of a palanquin-bearer whom the emperor Akbar

discovered and apprenticed to Abdus Samad, is a symbol of other Hindu artists

who practised the Persian way and created a new efflorescence of art. Another

great name at Akbar's court amongst the Hindu masters is Basawan. The practice

of signing pictures in this period of art history gives us names of artists at

Akbar's court of which a large number is given in the Ain-e-Akbari like Mukund,

Madhu, Khemkaran, Harbans, Kesavlal and others. The illustrated Babar Nama,

Akbar Nama, Hamza Nama, Razm Nama and other beautifully illustrated manuscripts

of the period are a great artistic achievement. Still in this period, the

Persian treatment of the background and the landscape is obvious, though slowly

this influence, diminishes in the successive periods. The building of Fatehpur

Sikri, the emperor's chase of wild animals and, particularly, the birth of his

second son Murad at Fatehpur Sikri are splendid illustrations in which the

Akbar Nama abounds.

The

story of Mughal painting in India may be said to have begun with Khwaja Abdus

Samad of Shiraz who was patronised by Humayun and continued in the time of

Akbar. Daswant, the poor son of a palanquin-bearer whom the emperor Akbar

discovered and apprenticed to Abdus Samad, is a symbol of other Hindu artists

who practised the Persian way and created a new efflorescence of art. Another

great name at Akbar's court amongst the Hindu masters is Basawan. The practice

of signing pictures in this period of art history gives us names of artists at

Akbar's court of which a large number is given in the Ain-e-Akbari like Mukund,

Madhu, Khemkaran, Harbans, Kesavlal and others. The illustrated Babar Nama,

Akbar Nama, Hamza Nama, Razm Nama and other beautifully illustrated manuscripts

of the period are a great artistic achievement. Still in this period, the

Persian treatment of the background and the landscape is obvious, though slowly

this influence, diminishes in the successive periods. The building of Fatehpur

Sikri, the emperor's chase of wild animals and, particularly, the birth of his

second son Murad at Fatehpur Sikri are splendid illustrations in which the

Akbar Nama abounds.  Jehangir's

son Shah Jahan was, though a connoisseur, more a builder of great monuments and

a pattern of architecture. Painting flourished, no doubt, during his day, but

its heyday was reached during the time of his father. The puritan Aurangzeb,

who imprisoned his father Shah Jahan and came to the throne, could not probably

provide encouragement to the art that he considered against the tenets of his

religion, and the disappointed artists of the Mughal court had slowly to find a

better atmosphere for survival elsewhere. Thus from this time onwards not only

music was buried deep but art also was driven away to different homes and the

provincial schools in Amritsar, Lahore, Lucknow, Oudh, Murshidabad, Golconda,

and other places absorbed the painters of the Moghal court who were driven to

seek a home elsewhere.

Jehangir's

son Shah Jahan was, though a connoisseur, more a builder of great monuments and

a pattern of architecture. Painting flourished, no doubt, during his day, but

its heyday was reached during the time of his father. The puritan Aurangzeb,

who imprisoned his father Shah Jahan and came to the throne, could not probably

provide encouragement to the art that he considered against the tenets of his

religion, and the disappointed artists of the Mughal court had slowly to find a

better atmosphere for survival elsewhere. Thus from this time onwards not only

music was buried deep but art also was driven away to different homes and the

provincial schools in Amritsar, Lahore, Lucknow, Oudh, Murshidabad, Golconda,

and other places absorbed the painters of the Moghal court who were driven to

seek a home elsewhere.

0 Response to "Mughal Emperor Sixteenth to Eighteenth Century A.D. "

Post a Comment