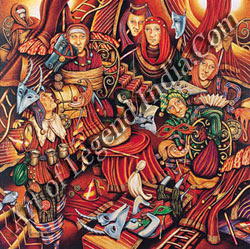

The

colours are soft and subdued, the lines firm and sinewy, the expression true to

life and, above all, there is an ease in the contours of these figures which

have a charm of their own.

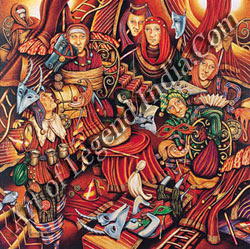

The

colours are soft and subdued, the lines firm and sinewy, the expression true to

life and, above all, there is an ease in the contours of these figures which

have a charm of their own.

In the

ninth century, the Cholas regained power, when Vijayalaya established himself

in the area round about Tanjavur. Aditya and Parantaka, the son and grandson of

Vijayalaya, were great temple-builders. Parantaka was specially devoted to Siva

at Chidambaram and covered the temple with gold. The widowed queen of the pious

king, Gandaraditya, son of Parantaka, is one of the most important queens in

Chola history for the generous tradition of building and endowing temples. The

most imposing monu-ment of the Chola period is the Rajarajesvara temple at

Tanjavur, also known as the Brihadisvara temple. Rajaraja was undoubtedly the

greatest ruler in the Chola line, great in military triumph, in organisation of

the empire, patron-age of art and literature, and in religious tolerance. In

the twenty-fifth year of his reign, a great and magnificent temple of Siva,

named after the king, Rajarajesvaramudayar, was completed. Rajaraja was so

intensely devoted to Siva that he was known by the epithet Sivapadasekhara. His

taste for art is reflected in the title Nit yavinoda. Rajaraja's glory was

partially eclipsed by that of his greater son Rajendra, who was a remarkable

military genius. Rajendra, on his return from a successful campaign in the

Gangetic area, created a huge tank, symbolic of a liquid pillar of victory, in

his own new capital, Gangaikondacholapuram, and a gigantic temple, resembling

the Brihadisvara at Tanjavur, to celebrate his triumph and the bringing home of

the Ganges water as the only tribute he sought from the vanquished sovereigns

of the North.

Kulottunga

II, the son of Vikramachola, made elaborate additions to the Chidambaram

temple. This interest was sustained in the reign of his son Rajaraja H whose

biruda, Rajagambhira, is recorded in the lovely rnandapa of the temple at

Darasuram, built during his time. Kulottunga III was the last of the great

Chola emperors to add to the Chola edifices, not only by building temples like

the Kampaharesvara at Tribhuvanam, but also by renovations and additions as at

Kanchi, Madurai, Chidambaram, Tiruvarur, Tiruvidaimarudur and Darasuram.

There

are fragments of very early Chola paintings at Narthamalai, Malayadipatti and

other places. However, it is the Brihadisvara temple at Tanjavur that is a real

great treasure-house of the art of the early Chola painter. The contemporary

classics describe the glory of the paintings in the South by referring to chit

ramandapas, chitrasalas, oviyanilayams in temples and palaces. The Paripadal

men-tions the paintings on temple walls in the early Chola capital,

Kaveripumpattinam. The actual remains of this period are, however, yet to be

discovered. In the Vijayalayacholisvaram temple on the hill at Narthamalai,

there are traces of paintings on the walls showing the dancing figure of Kali

and Gandharvas on the ceiling of the antechamber.

S.K.

Govindaswami's discovery of paintings in the dark circumambulatory passage

around the central shrine in the Brihadisvara temple at Tanjavur revealed a new

phase of South Indian painting, a regular picture gallery of early Chola art.

There are two layers, one of the Nayak period on top, which, wherever it has

fallen, has revealed an earlier Chola one below, richly laden with painting.

The

entire wall and the ceiling were originally deco-rated with exquisite paintings

of the time of Rajaraja, but later renovation and additions made during the

centuries account for additional layers that have covered up the earlier one.

These Chola paintings that form an important link in the series help a better

study of the earlier Pallava phase and the later Vijayanagara. The Chola

paintings so far exposed are mainly on the western and northern walls. On the

western side, the entire wall space consists of a huge panel with Siva as

Yoga-Dakshinamurti, seated on a tiger-skin in a yogic pose, with the yogapatta

or paryankabandha across his waist and right knee, calmly watching the dance of

two apsaras. A dwarf gana and Vishnu play the drum and keep time, while other

celestials in a row sound the drum, the hand drum and the cymbals, as they fly

in the air, to approach this grand spectacle, which is witnessed by a few

principal figures seated in the foreground. Saint Sundara and Cheraman are

shown below hurrying thither on a horse and an elephant, respectively. A little

away is a typical early Chola temple enshrining Nataraja with princely devotees

seated in its vicinity.

Lower

down is the narration of the story of Sundara, how Siva came in the guise of an

old man, with a document, to prove his right and claim the beautiful bridegroom

to take him away on the very day of his marriage to his abode at

Tiruvennainallur. Below this is the scene of marriage festivity. On the wall

beyond, there is a large figure of Nataraja, dancing in the hall at

Chidambaram, with priests and devotees on one side and a prince, obviously

Rajaraja and three of his queens, with a large retinue adoring the lord. Close

by, on the walls opposite, are some charming miniature feminine figures. Beyond

this, on the wall opposite the northern one, are five heads peeping out of a

partially exposed Chola layer.

The

whole space on the northern wall has for its theme the fight of Tripurantaka.

The gigantic figure of Siva is on a chariot driven by Brahma. Tripurantaka is

shown in the alidha pose of a warrior, with eight arms fully equipped with

weapons, using his mighty bow to overcome the asuras, a host of whom the

painter has depicted opposite Siva, with the fierce indomitable spirit clearly

portrayed in their attitude, fierce eyes, flaming hair and upraised weapons,

daunted by nothing, little caring for the fears or tears of their women as they

cling to them in fear and despair. Less as aids and more as companions of Siva

are shown Kartikeya on his peacock, Ganesa on his mouse and Kali, the

war-goddess, on her lion. Nandi is shown complacently quiet in front of his

chariot. This is a great masterpiece of Chola art. This figure of Tripurantaka

in the alidha pose in the Pallava tradition is seated and is a remarkable specimen

continuing the earlier mode.

The

paintings in the Brihadisvara temple constitute the most valuable document on

the state of the painter's art during the time of the early Cholas, all the

grace of classical painting observed at Sittannavasa, Panamalai and Kanchipuram

being continued in this fine series.

The

Chola paintings reveal to us the life, the grandeur and the culture of the

Chola times. The special stress on Nataraja in his sabha hall as a favourite

deity of the Cholas and the military visions and ideals of the Cholas in general,

and of Rajaraja in particular, are almost symbolically ex-pressed in the great

masterpiece of Tripurantaka.

The

colours are soft and subdued, the lines firm and sinewy, the expression true to

life and, above all, there is an ease in the contours of these figures which

have a charm of their own.

The

colours are soft and subdued, the lines firm and sinewy, the expression true to

life and, above all, there is an ease in the contours of these figures which

have a charm of their own.

If

expression is to be taken as the criterion by which a great painter has to be

judged, it is here in abundance in these Chola paintings. The sentiment of

heroism, virarasa, is clearly seen in Tripurantaka's face and form. The

vigorous attitude of the Rakshasas determined to fight Siva and the wailing

tear-stained faces of their women clinging to them in despair suggest an

emotion of pity, karuna and raudra. Siva as Dakshinamurti seated calm and

serene is a mirror of peace, santa. The hands in the vismaya of the dancer

suggests the spirit of wonder, adbhuta; the grotesque dwarf ganas in funny

attitudes playing the drum and keeping time represent hasya; the commingling of

emotion is complete in the large Tripurantaka panel which is a jumble of vira,

raudra and karuna.

Writer – C. Shivarammurti

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Chola Emperor Ninth to Thirteenth Century A.D. "

Post a Comment