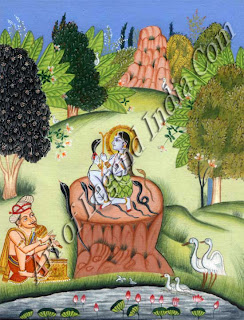

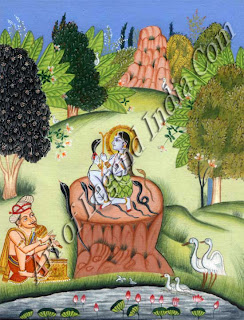

Curiously, this illustration of

Asavari Ragini is identified by a label in the upper border as "the ragini

of Dipak Raga, number 36" instead of the wife of Sri Raga, which in the

Rajasthani tradition the ragini is normally regarded to be. Iconographically,

this work presents a much more detailed and expanded version (or vision) of

Asavari Ragini than painting A. The simple heroine has been transformed into

the goddess Savari, the Saiva tutelary deity of the Savaras. Her identity and

divinity are indicated, respectively, by her blue skin, denoting her tribal

origins, and by her golden nimbus and crescent moon, emblematic of Siva and

Saiva goddesses. This socioreligious elevation is also suggested by her now

copious gold-and-pearl jewelry. place of a simple stick the goddess waves an

ascetic's crutch in front of a cobra. She sits enthroned on a hilltop plateau

symbolic of the Malaya mountains, a compositional feature much more

representative of Asavari Raginis than the humble platform of painting A. The

forest is also imbued with greater life and variety. Lush blooming trees, a

hallmark of Bundi painting, draw the viewer along the recession toward the

mountains in the background. Swans and Brahminy ducks gather around a lotus

pond in the foreground, a compositional element equally typical of Bundi

painting. A snake-charmer playing a bulbous flute (pritigi) completes the

composition. Ragamala paintings were particularly popular in Bundi, both as

album folios and palace murals.

Curiously, this illustration of

Asavari Ragini is identified by a label in the upper border as "the ragini

of Dipak Raga, number 36" instead of the wife of Sri Raga, which in the

Rajasthani tradition the ragini is normally regarded to be. Iconographically,

this work presents a much more detailed and expanded version (or vision) of

Asavari Ragini than painting A. The simple heroine has been transformed into

the goddess Savari, the Saiva tutelary deity of the Savaras. Her identity and

divinity are indicated, respectively, by her blue skin, denoting her tribal

origins, and by her golden nimbus and crescent moon, emblematic of Siva and

Saiva goddesses. This socioreligious elevation is also suggested by her now

copious gold-and-pearl jewelry. place of a simple stick the goddess waves an

ascetic's crutch in front of a cobra. She sits enthroned on a hilltop plateau

symbolic of the Malaya mountains, a compositional feature much more

representative of Asavari Raginis than the humble platform of painting A. The

forest is also imbued with greater life and variety. Lush blooming trees, a

hallmark of Bundi painting, draw the viewer along the recession toward the

mountains in the background. Swans and Brahminy ducks gather around a lotus

pond in the foreground, a compositional element equally typical of Bundi

painting. A snake-charmer playing a bulbous flute (pritigi) completes the

composition. Ragamala paintings were particularly popular in Bundi, both as

album folios and palace murals.

Asavari Ragini is a somber

melody of the early morning, generally considered to be a wife of Sri Raga. The

name is taken from that of the Savaras, an ancient jungle tribe renowned for

its snake-charming skills and from whose fluted tunes the ragini is said to

derive. The literary descriptions of Asavari Ragini exhibit considerable

variance; those corresponding most closely to the Rajasthani-tradition

paintings are found in the early seventeenth-century Sangitadarpana of Damodara

Misra and a number of other texts paintings of Asavari Ragini display a

consistent basic imagery, a woman in the forest communing with cobras, with

minor variations She is usually garbed in a leaf skirt, as in the present

examples; alternatively she is naked or dressed in aristocratic filter Consistent

with the ragini's cultural origin, the heroine displays a ,mastery over the

serpents and interacts with them in a number of ways. She can be Shown taming

them by hand, through the use of a wind instrument, or by instructing them by

hand gestures or the movements of a small stick, usually shaped and brandished

like an orchestra conductor's baton. Occasionally, as in painting, male

snake-charmers are shown performing their melodic spells. These movements of

the stick flute or hands accord with the belief that it is the hypnotic, serpentine

movements of Indian snake charmers flutes rather than their actual melodies

that mesmerize cobras.

These two illustrations of

Asavari Ragini, created slightly more than a century and a half apart,

represent an early and a mature stage in the development of the imagery

associated with the ragini. Although both depict a leaf-clad heroine

accompanied by serpents in a forest, traditionally identified as the

snake-infested sandalwood groves of the Malaya mountains in Kerala, there are

significant differences between the two representations.

In this painting, a minimally

adorned heroine holds one cobra while others slither around her legs, the

wooden platform on which she sits, and the tree trunk. The forest is indicated

by the two deciduous trees sheltering her as well as by the plantain trees and

flora. The subdued browns and greens of the palette, similar to those in the

illustration of Vasant Ragini, typify the productions of subimperial Mughal

painting workshops.

Curiously, this illustration of

Asavari Ragini is identified by a label in the upper border as "the ragini

of Dipak Raga, number 36" instead of the wife of Sri Raga, which in the

Rajasthani tradition the ragini is normally regarded to be. Iconographically,

this work presents a much more detailed and expanded version (or vision) of

Asavari Ragini than painting A. The simple heroine has been transformed into

the goddess Savari, the Saiva tutelary deity of the Savaras. Her identity and

divinity are indicated, respectively, by her blue skin, denoting her tribal

origins, and by her golden nimbus and crescent moon, emblematic of Siva and

Saiva goddesses. This socioreligious elevation is also suggested by her now

copious gold-and-pearl jewelry. place of a simple stick the goddess waves an

ascetic's crutch in front of a cobra. She sits enthroned on a hilltop plateau

symbolic of the Malaya mountains, a compositional feature much more

representative of Asavari Raginis than the humble platform of painting A. The

forest is also imbued with greater life and variety. Lush blooming trees, a

hallmark of Bundi painting, draw the viewer along the recession toward the

mountains in the background. Swans and Brahminy ducks gather around a lotus

pond in the foreground, a compositional element equally typical of Bundi

painting. A snake-charmer playing a bulbous flute (pritigi) completes the

composition. Ragamala paintings were particularly popular in Bundi, both as

album folios and palace murals.

Curiously, this illustration of

Asavari Ragini is identified by a label in the upper border as "the ragini

of Dipak Raga, number 36" instead of the wife of Sri Raga, which in the

Rajasthani tradition the ragini is normally regarded to be. Iconographically,

this work presents a much more detailed and expanded version (or vision) of

Asavari Ragini than painting A. The simple heroine has been transformed into

the goddess Savari, the Saiva tutelary deity of the Savaras. Her identity and

divinity are indicated, respectively, by her blue skin, denoting her tribal

origins, and by her golden nimbus and crescent moon, emblematic of Siva and

Saiva goddesses. This socioreligious elevation is also suggested by her now

copious gold-and-pearl jewelry. place of a simple stick the goddess waves an

ascetic's crutch in front of a cobra. She sits enthroned on a hilltop plateau

symbolic of the Malaya mountains, a compositional feature much more

representative of Asavari Raginis than the humble platform of painting A. The

forest is also imbued with greater life and variety. Lush blooming trees, a

hallmark of Bundi painting, draw the viewer along the recession toward the

mountains in the background. Swans and Brahminy ducks gather around a lotus

pond in the foreground, a compositional element equally typical of Bundi

painting. A snake-charmer playing a bulbous flute (pritigi) completes the

composition. Ragamala paintings were particularly popular in Bundi, both as

album folios and palace murals.

Writer

– Janice Leoshko

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Introduction to Asavari Ragini"

Post a Comment