ALTHOUGH

pilgrimage figures importantly in the religions of India, it never had any

canonical status in non-tantric traditions. In tantric literature and practice,

however, both Hindu and Buddhist, pilgrimage and its corollaries especially

circumambulatory rites which are central to the pilgrims progress have a much

higher prestige, so much so that it might almost be called canonical, if that

term could be properly applied to tantrism.

In

making a survey of Indian centres of pilgrimage, one thing emerges most

forcefully: at places which are not officially linked with the tantric

tradition, tantric elements become evident at every step. And although we have

to concentrate on shrines which are traditionally linked with tantric

literature and precept, we have to bear in mind that local traditions in almost

all shrines in India their number is legion have strong tantric elements,

whether this is conscious to the priesthood and the laity visiting those

shrines or not.

One

tends to identify pilgrim centres as tantric which have the flavour of extreme,

bizarre and esoteric austerity. But such painful prostrations,

self-humiliations, and disciplines bordering on the masochistic as I described

in another place1 are not necessarily tantric. And yet, such somewhat elusive

elements as the sprinkling of wine on the prasada (food offerings distributed

among the votaries) at jagannath, Puri, the shaving ritual for boys of certain

castes at such widely disparate places as Jvalamukhi in the Panjab, and Palni

in Madras State are definitely tantric in origin and connotation.

The

local lore at the shrines of India is one of the most direct means of telling

whether the place is fundamentally tantric or not. This takes us into the most

important mythological complex connected with tantric shrines and tantric

worship. The story of Daksa's sacrifice and of the subsequent events is pivotal

to tantric sanctuary-topography, as is the mythology ascribed to each

individual place of pilgrimage.

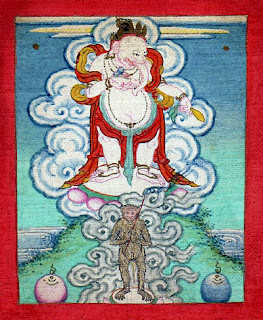

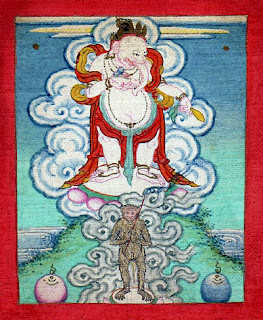

,+Late+19th+early+20th+Century,+Dhodeydrag+Gonpa,+Thimphu,+Bhutan.jpg) The

most important myth of tantric relevance is, then, no doubt, the story of

Daksa's sacrifice; it is told, in many minor and major variations, in all the

Puranas, and in the Epic. It is imperative to pursue this particular myth in

some detail; valuable information about its development has been furnished by

D. C. Sircar. In the tantric tradition, a centre of pilgrimage is called a

`pitha', a 'scat' of the goddess; tantric literature rarely uses the more

general word `tirtha'; probably the distinction itself depends on the

mythological relevance of the centre: shrines of the goddess are pithas,

sanctuaries of gods, or mixed shrines (i.e. where a god and a goddess are

worshipped), are called tirthas just as non-tantric worshippers would call

them. Pitha' seems to be a purely tantric term in the first place, although it

has gained currency in other, not necessarily religious, contexts in the last

two centuries; thus, several colleges teaching classical subjects in the Indian

tradition are called pithas, quite literally `seats of learning', as for instance

the Kashi Vidya pitha, one of the best institutes of higher education at

Banaras.

The

most important myth of tantric relevance is, then, no doubt, the story of

Daksa's sacrifice; it is told, in many minor and major variations, in all the

Puranas, and in the Epic. It is imperative to pursue this particular myth in

some detail; valuable information about its development has been furnished by

D. C. Sircar. In the tantric tradition, a centre of pilgrimage is called a

`pitha', a 'scat' of the goddess; tantric literature rarely uses the more

general word `tirtha'; probably the distinction itself depends on the

mythological relevance of the centre: shrines of the goddess are pithas,

sanctuaries of gods, or mixed shrines (i.e. where a god and a goddess are

worshipped), are called tirthas just as non-tantric worshippers would call

them. Pitha' seems to be a purely tantric term in the first place, although it

has gained currency in other, not necessarily religious, contexts in the last

two centuries; thus, several colleges teaching classical subjects in the Indian

tradition are called pithas, quite literally `seats of learning', as for instance

the Kashi Vidya pitha, one of the best institutes of higher education at

Banaras.

As

Professor Sircar's treatment can hardly be improved upon, I shall reproduce it

in portions, so far as it is relevant to our survey.

…The

earliest form of the legend of Daksa-yajna-nasa is probably to be traced in the

Mahabharata (XII, chapters 282-3; cf. Brahma Purana, ch. 39) and a slightly

modified form of the same story is found in many of the Puranas (Matsya, ch.

12; Padma, Srstikhanda, ch. 5; Karma, I, ch. 15; Brahmanda, ch. 31, etc.) as

well as in the Kumarasambhava (I, 2!) of Kalidasa who flourished in the fourth

and fifth centuries and adorned the court of the Gupta Vikramadityas. According

to this modified version of the legend, the mother-goddess, who was the wife of

Siva, was in the form of Sati one of the daughters of Daksa Prajapati. Daksa

was celebrating a great sacrifice to which neither Sati nor Siva was invited.

Sati, however, went to her father's sacrifice uninvited, but was greatly

insulted by Daksa. As a result of this ill-treatment, Sati is said to have died

by yoga or of a broken heart, or, as Kalidasa says, she immolated herself and

perished. . . . When the news of Sati's death reached her husband, Siva is said

to have become furious and hastened to the scene with his numerous attendants.

The sacrifice of Prajapati Daksa was completely destroyed. Siva, according to

some of the sources, decapitated Daksa, who was afterwards restored to life and

thenceforward acknowledged the superiority of Siva to all gods. . . .

In

still later times, probably about the earlier part of the medieval period, a

new legend was engrafted to the old story simply for the sake of explaining the

origin of the Pithas. According to certain later Puranas and Tantras (Devibhagavata,

VII, ch. 30; Kalika Purana, ch. 18 ; etc.), Siva became inconsolable at the

death of his beloved Sati, and after the destruction of Daksa's sacrifice he

wandered over the earth dancing madly with Sati's dead body on his shoulder

(or, head). The gods now became anxious to free Siva from his infatuation and

conspired to deprive him of his wife's dead body. Thereupon Brahma, Vishnu and

Sani entered the dead body by yoga and disposed of it gradually. The places

where pieces of Sati's dead body fell arc said to have become Pithas, i.e. holy

scats or resorts of the mother-goddess, in all of which she is represented to

be constantly living in some form together with Bhairava, i.e. a form of her

husband Siva. According to a modified version of this story, it was Vishnu who,

while following Siva, cut Sati's dead body on Siva's shoulder or head piece by

piece. The story of the association of particular limbs of the mother-goddess

with the Sakta tirthas, which may have some relation with the Tantric ritual

called Vithanyasa,4 belongs, as already pointed out, to the latest stage in the

development of an ancient talc. But the story may have some connection with

Buddhist legends regarding the worship of Buddha's bodily relics and the

construction of Stupas in order to enshrine them as well as with those

concerning the various manifestations of Buddha in the Jambudvipa.

The

tantric tradition of four pithas was not known to occidental scholars until

recently. Monier Williams seems to have had a vague idea about four shrines

dedicated to the goddess. He wrote: 'There are also four celebrated shrines of

goddesses: Mahalaksmi at Kolapur, Bhavani near Sholapur, Renuka at Matapura,

Yogesvari about 8o miles from Ahmednagar.'

Most

of the early tantras, both Buddhist and Hindu, refer to four pit has. Sircar

thinks that the conception of the four pithas may have been associated with the

Buddhist tantric notion according to which the adept can rise to mahasukha

('the great bliss') through the esoteric practices involving sex.6 He quotes a

Buddhist tantric text called Catuspithantantra (the tantra of the four pithas)

and its commentaries, one of which was copied in A.D. 1145. This text speaks of

four pithas as `atmapitha' (the 'shrine of the self' strange-sounding Buddhism

indeed, but not infrequent in Sanskrit Buddhist terminology), para-pitha (the

shrine of the supreme), yoga-pitha (which is self-explanatory), and guhya-pitha

(the secret, esoteric shrine), and it deals with the various kinds of

Vajrasattvas and their intercourse with the Yoginis, with Prajnaparamita and

others. `This philosophical concept,' D. C. Sircar avers (p. 11), 'of the

Catuspitha was either the cause or the effect of the early recognition of four

holy places as pithas.' He adds in a footnote (ibid.), `it is difficult to

determine what relation the Catuspitha could have with the Catuspitha Mountain

near Jajpur in Orissa, and with other Sahajayana conceptions of

"four", e.g. the Caturananda, the four-fold bliss'. The Hevajra

Tantra, composed around ,10 690 A.D. enumerates the four pit has, and to my

knowledge this is the earliest enumeration: (1) Jalandhara (definitely near the

present .Jullundar, East Panjab); (2) Oddiyana (or Uddiyana), Urgyan in

Tibetan, misspelt `Udyana', viz. 'garden' in the Bengali DohaKola (ed.

Shahidullah) in the Swat Valley; (3) Purnagiri (the location is doubtful), and

(4) Kamarapa (Kamrup in Assam at present the only pitha 'in action').

The

same tradition is followed by the Kalika Purana (ch. 64, 43-5), which calls

them (1) Odra, 'seat of the goddess Katyayani and the god jagannatha, (2)

Jalasaila, seat of the goddess Candi and the god Mahadeva, (3) Puma or

Purnasaila, seat of the goddess Purnesvari and the god Mahanatha, and finally

(4) Kamarupa, seat of the deities Kamesvari and Kamesvara. These four 'pithas'

are allocated to the four directions, but this is pure theory, and stands in

accordance with the tradition to allocate every ritualistic locale to a

direction of the compass, and hence to group them either in fours or in tens,

sometimes in groups of eight (i.e. omitting the zenith and the nadir). In

geographical reality, however, the distribution of the four main pithas is very

irregular indeed: Oddiyana, in the Swat Valley, is the only far-western site

Kamarupa and possibly Purnagiri are in the extreme east and Jalandhara again in

the middle north-west (Panjab). None of the four pit has is situated in the

south, in spite of the fact that the Kerala region has a strong Salta and

tantric element in its culture; in some form or another Sakti is the tutelary

deity of Kerala." I shall now present a token topography of tantric

sanctuaries.

The

same tradition is followed by the Kalika Purana (ch. 64, 43-5), which calls

them (1) Odra, 'seat of the goddess Katyayani and the god jagannatha, (2)

Jalasaila, seat of the goddess Candi and the god Mahadeva, (3) Puma or

Purnasaila, seat of the goddess Purnesvari and the god Mahanatha, and finally

(4) Kamarupa, seat of the deities Kamesvari and Kamesvara. These four 'pithas'

are allocated to the four directions, but this is pure theory, and stands in

accordance with the tradition to allocate every ritualistic locale to a

direction of the compass, and hence to group them either in fours or in tens,

sometimes in groups of eight (i.e. omitting the zenith and the nadir). In

geographical reality, however, the distribution of the four main pithas is very

irregular indeed: Oddiyana, in the Swat Valley, is the only far-western site

Kamarupa and possibly Purnagiri are in the extreme east and Jalandhara again in

the middle north-west (Panjab). None of the four pit has is situated in the

south, in spite of the fact that the Kerala region has a strong Salta and

tantric element in its culture; in some form or another Sakti is the tutelary

deity of Kerala." I shall now present a token topography of tantric

sanctuaries.

The

canonical tantric text listing the `pithas' is the Pithanirnaya (description of

tantric seats'), also called the Mahapithapurana; the latter name indicates

that the work has a sort of mongrel position it is a tantra by virtue of its

dealing with properly tantric material, and a purana by courtesy, as it were,

probably because it can be said to describe its objects satisfying the `pancalaksana-s,'

i.e. the five criteria of a purana. The text lists io8 pithas following the

tradition of the sacred number 108, on which there has been much speculation;

the author does not seem to have been worried about the lack of choice there

are no repetitions of any place name, not even under the guise of a

topographical synonym. Other tantric texts list pithas not mentioned in this

text, but it can hardly be established with complete certainty whether or not a

pitha mentioned in one text is or is not identical with one of the same name in

another. Thus, the Kubjika Tantra lists a pitha `Mayavati,' and so does the

Pithanirnaya; they may be identical, but their respective juxtaposition with

other pithas of established location would indicate that they are not. Very

often a general epithet is given to a proper name or a place name, and it is

customary to use the epithet in lieu of the proper name, it being understood

that the people who read the text are familiar with the nomenclature. But

Mayavati, i.e. 'full of Maya' or 'like Maya'', (cosmic illusion or enticement)

applies to at least three great shrines Banaras, Ayodhya, and Brindavan and

once an epithet like this has been used for any location by a popular teacher

or author, the epithet comes to stay.

It

does not become directly clear from the texts why the four pithas (Oddiyana,

Srihatta, Purnagiri, Jalandhara) were almost unanimously accepted as the most

outstanding in all tantric tradition, Buddhist and Hindu alike. I would hazard

the guess that the high esteem for these four places might have something to do

with the mythological eminence of the sites: a pitha, by mythological

definition, is a site where a limb of the goddess fell to earth when her body

was being chopped up by the gods (after the Daksa episode); at these four

pithas, however (though unfortunately not only at these four), the magically

most potent limbs of Sati descended: her pudenda, her nipples, and her tongue.

The

most important phenomenon of tantric pilgrimage, both as a concept and as a set

of observances, is the hypostasization of pilgrim-sites and shrines: the

geographical site is homologized with some entity in the esoteric discipline,

usually with a region or an 'organ' in the mystical body of the tantric

devotee. This sort of homologizing and hypostasy began early." It became

ubiquitous in the tantric tradition. Centres of pilgrimage fell well into this

pattern and Hindu and Buddhist literature abound in examples of such

hypostasization. Professor Eliade, who was the first to formulate it, put it

thus:

All

'contacts' with the Buddha are homologized; whether one assimilates the

Awakened One's message that is, his 'theoretical body' (the dharma) or his

'physical body', present in the stupas, or his 'architectonic body' symbolized

in temples, or his 'oral body' actualized by certain formulas each of those

paths is valid, for each leads to transcending the plane of the profane. The

'philosophers' who 'relativized' and destroyed the immediate 'reality' of the

world, no less than the mystics who sought to transcend it by a paradoxical

leap beyond time and experience, contributed equally toward homologizing the

most difficult paths (gnosis, asceticism, yoga) with the easiest (pilgrimages,

prayers, mantras). For in the 'composite' and conditioned world, one thing is

as good as another; the unconditioned, the Absolute, nirvana, is as distant

from perfect wisdom and the strictest asceticism as it is from . . . homage to

relics, etc. . . .

The

Mantramahodadhi has a section entitled `the nyasa of the pit has

(pitha-nyasa-kathanam). Literally, nyasa is the process of charging a part of

the body, or any organ of another living body, with a specified power through

touch. For instance, by placing the fire-mudra on the heart-region uttering the

fire-mantra 'ram', the adept's heart is made into the cosmic fire; and by

meditating on a specific pitha with the mantra of its presiding Sakti', the

very region (for instance the heart, or the navel, or the throat) wherein the

Sakti is thus visualized is hypostasized or trans-substantiated, into that

pitha. The tantric formulation would be: Meditating on the pilgrim-centre

through visualizing its presiding deity in the prescribed manner, the locus of

concentration in the yogi's body is charged with the spiritual efficacy of that

very place. With the Buddhist tantrics, the pattern is transparent even on a

purely doctrinal basis for no `place of pilgrimage' exist in an ontological

sense.

The

Mantramahodadhi has a section entitled `the nyasa of the pit has

(pitha-nyasa-kathanam). Literally, nyasa is the process of charging a part of

the body, or any organ of another living body, with a specified power through

touch. For instance, by placing the fire-mudra on the heart-region uttering the

fire-mantra 'ram', the adept's heart is made into the cosmic fire; and by

meditating on a specific pitha with the mantra of its presiding Sakti', the

very region (for instance the heart, or the navel, or the throat) wherein the

Sakti is thus visualized is hypostasized or trans-substantiated, into that

pitha. The tantric formulation would be: Meditating on the pilgrim-centre

through visualizing its presiding deity in the prescribed manner, the locus of

concentration in the yogi's body is charged with the spiritual efficacy of that

very place. With the Buddhist tantrics, the pattern is transparent even on a

purely doctrinal basis for no `place of pilgrimage' exist in an ontological

sense.

Going

back for a moment to the Mantramahodadhi, the section says: `He should meditate

on his body as the "pitha" by doing "nyasa" of the

tutelary. Pitha-deity. He should make "nyasa" of the Namduka flower

(Clerodendrum Syphonantum) in his base-centre (adhara); in the heart, there are

all the pithas of the earth, the ocean, the jewel island, and of the snowy

palace (i.e. the Himalayas), if he can pull up the Adhara-Sakti there:'

The

Buddhist tantric Caryapadas, all of which are contained in the Tanjur and many

of which are extant in their old Bengali originals, are replete with

hypostases. An example: `The path along which the boat is to sail is the

middle-most one in which both the right and left are combined, that is located

between the Ganges and the Yamuna, and along this path which is beset with

dangers the boat has to proceed against the current.' All this is Sandhabhasa

(intentional language) and is easily understood once the terminology is known.

The 'Ganges' and `Yamuna' are the left and the right ducts in the yogic body,

the middle-most is the `avadhuti' or the central duct which has to be opened by

the controls created through meditation.

The

Hevajra Tantra gives a beautiful instance of hypostasis: Vajragarbha said:

What, O Lord, are these places of meeting? The Lord replied: They are the pitha

and the upapitha, the ksetra and upaksetra, the chandoha and the upachandoha .

. . etc. These correspond with the twelve stages of a Bodhisattva. It is

because of these that he receives the title of Lord of the ten stages and as

Guardian Lord. Vajragarbha asked: What are these pithas? The Lord said: They

are Jalandhara, Oddiyana, Purnagiri, Kamarupa.' He then lists a further 32

places.

A

Doha by Saraha illustrates the hypostasis in a poetical manner:

'When the mind goes to rest, the bonds of the body are

destroyed,

And when the one flavour of the Innate pours forth,

There is neither

outcaste nor Brahmin.

Here is the sacred Yamuna and here the River Ganges,

Here are Prayaga and Banaras, here are Sun and Moon.

Here I have visited in my wanderings shrines and such places

of pilgrimage.

For I have not seen another shrine blissful like my own body.’

In a

treatment of non-tantric pilgrimage, the circumambulation-pattern which now

follows would perhaps not have to be included. However, in tantrism it is so

much a part of the process of pilgrimage that it must form the concluding, if

not the most important, section of this chapter.

In a

treatment of non-tantric pilgrimage, the circumambulation-pattern which now

follows would perhaps not have to be included. However, in tantrism it is so

much a part of the process of pilgrimage that it must form the concluding, if

not the most important, section of this chapter.

We

do not know if circumambulation was a custom in pre-Vedic India; aboriginal

tribes all over India (especially the Santhals of Bihar) circumambulate their

houses and shrines rather more frequently than the neighbouring caste-Hindu

groups; but it is hard to say whether these autochthonous groups are preserving

a pre-Aryan custom or whether they have simply taken it over from the Hindu

ritual.

Tantric

literature contains elaborate instruction about circum-ambulation, pradaksina

('walking clockwise'), and there is hardly a tantric text or manual lacking

such instruction. Scanning the tables of contents of a dozen tantric texts at

random, I found only one (the Mantramahodadhi, ed. Khemraj Srikrisnadass,

Bombay) whose table of contents did not list pradaksina as a section though

this popular manual does contain such instructions under different headings. I

shall quote an example from the large Mantramaharnava'. The section is

captioned 'pradaksina nirnaya', 'definition' or 'description of pradaksina',

and it is listed among other nirnaya-s' preceding and following it, i.e.

neither more nor less important than these: description of incense

(gandha-nirnaya), of fruit and flowers to be offered (phala-puspanirnaya), of

raiments to be worn (vastranirnaya), then comes our pradaksina-nirnaya, and

others follow. These nirnayas usually stand at the beginning of the text. It

says 'now then the description of pradaksina: according to the Lingarcanacandrika

("the moon-rays of Linga-worship" an extant but hitherto unpublished

text) one pradaksina for (the goddess) Candi, seven for the Sun, three (are to

be done) for Ganesa; four for Hari (Vishnu), for Siva half a pradaksina'. This

may seem strange in a tantric work, Siva being the tutelary deity of all the

tantras; however, the implication seems to be that because so many other bits

of ritual arc performed for Siva and listed in other parts of the manual there

was no need felt for more than the minimum pradaksina which is half a circum-ambulation.

This also seems negatively implied by the great number of pradaksinas to the

Sun, a Vedic deity not very close to the tantrics; apart from the

water-oblation (tarpana) offered to the

Sun,

there is only this sevenfold pradaksina mentioned in the manual. I surmise that

the feeling of some tantrics has been that pradaksina was something essentially

Vedic, and then the unspoken formula might be something like 'more (Vedic)

pradaksina, less tantric ritual; more tantric ritual, fewer pradaksinas'. If we

test this hypothesis by the verse quoted here and by numerous similar passages

it is certainly corroborated. Siva has the greatest number of typically tantric

rituals, Candi (identical with Camundi, Kali the Vajrayana Buddhist goddesses,

and the non-Aryan autochthonous goddesses in general) very many indeed as a

typically tantric goddess and as the many-splendored spouse of Siva; Vishnu and

Ganesa have some very few purely tantric rituals, the Sun none, although the

Vedic tarpana or water offering has been taken over into the tantric tradition

without any change.

The

next two verses are captioned 'the greatness of pradaksina for Siva', and they

run 'he who has performed formal worship and who does not do pradaksina for Sambhu

(Siva), his worship is fruitless, and the worshipper is a cheat (dambhika);

(but) he who performs just only this one correct pradaksina with devotion (to Siva),

all worship has been done by such a man, and he is a true devotee of Siva'.

The

next two verses are captioned 'the greatness of pradaksina for Siva', and they

run 'he who has performed formal worship and who does not do pradaksina for Sambhu

(Siva), his worship is fruitless, and the worshipper is a cheat (dambhika);

(but) he who performs just only this one correct pradaksina with devotion (to Siva),

all worship has been done by such a man, and he is a true devotee of Siva'.

In

the Dravidian south, pradaksina seems to be particularly popular in the worship

of indigenous deities. The Naga deities represented by snake-idols of various

shapes and sizes on a plinth usually at some distance from the shrines of the

main (Brahmin) deities, or under specific trees in the villages are chiefly

deities of fertility and the life-cycle. They are also installed on the

viriksa-vivaka-manthapam (Sanskrit vrksa-vivaha-mandapam, i.e.

'tree-marriage-platform' a platform erected around two intertwined trees which

are fairly frequent all over India; such trees are said to be `married'), which

women circumambulate 'on Mondays in order to remove Carppa Tosam (Sanskrit

Sarpa-dosa), the curse of barrenness, a curse incurred by harming a snake

either directly or indirectly as by some relative, ancestor, etc."

However, pradaksina is the regular procedure on any temple visit, especially in

the south, where the temples have spacious pradaksinas i.e. ambulatories. The

pradaksina is done immediately after the worship in the shrine, sometimes before

and after. Also the idol or rather, a small, portable replica of the idol in

the shrine is carried around those pradaksinas every day by the temple priests,

with nadasvaram (south Indian reed-horns, somewhat like a shawm) accompanying

the procession. The musicians walk some distance ahead, the pious follow the

image, several times on festive occasions.

Although

`pirataksinam' (Tamil for pradaksina) is known to most Dravidians who visit

Brahmin temples, the indigenous Dravidian word is `valttu', from the Tamil root

`var, to salute. The Akkoracivacariyar, a manual for Tamilian temple-officials,

prescribes 'The Acariyar (head priest) comes to the temple 3 and 3/4 nalikai

(i.e. about an hour and a half) before sunrise; after having completed his

anusthanam (the initial observances), he washes his hands and feet, makes

pirataksinam by walking round the sanctum turning his right side towards it,

salutes the (guardians of the gate) tuvarapalakar, Sanskrit dvarapalaka, the

figures placed at each side of the entrance), and reaching the place in front

of the sacred bull (Nandi his image is found in every Siva temple, facing the

deity), pronounces the basic mantra and offers flowers.'

At

the Somasundara Temple in Madurai (Tamilnad), some devotees circumambulate the

shrine nine times, while a pattar (a sort of auxiliary priest) throws a flower

on one each of the nine idols representing the navagrahas (the nine

constellations) on their behalf. A monk or some other religious mendicant

usually stands at hand who, for a small fee, will throw incense on a charcoal

fire as an offering as the visitors perform their pradaksina. There are dozens

of variations in the pradaksina-routine in different shrines, and there is much

more heterogeneity in the south than in the north.

The

more tortuous kinds of pradaksina are well known to tourists and photographers;

on Mount Abu the famous Jaina sanctuary in Gujarat I witnessed a group of

pilgrims in June 1955 who measured the entire ambiance of the sacred mount,

roughly two miles, by constant prostrations in what they call the ‘dehamap'

method in Gujarati (i.e. the 'measure of the body') facing the direction of the pradaksina they

prostrate, then stand up, placing their feet exactly on the spot where they had

touched the ground with their foreheads, then prostrate again and repeating the

process until the pradaksina is complete or until they pass out. That particular

pradaksina, I was told, takes an average of thirty hours; the pilgrims do rest

in between, however, but they do not take any solid food until they have

completed it.

I

have not seen any texts, however, which would prescribe these painful kinds of

religious observance. If there are, they would belong to the category of

pilgrim's-pamphlets such as are distributed at the various shrines all over

India; they are always in the vernacular, and have none but purely local

status. No widely accepted instruction manual would recommend self-inflicted

hardship of this sort.

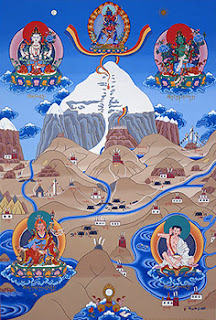

A

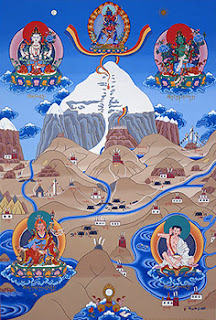

word must be said about the pradaksina of Mt. Kailasa in Tibet. In 1951 over

six hundred Indian pilgrims undertook the pilgrimage on the route Almora,

Pituragarh, Garbiang, Lipulek, Taghlakot. The Hindus regard Mt. Kailasa as the

abode of Siva and Parvati, ‘Kailasanatha', ‘Kailasapati’, etc., being frequent

names of Siva, and common male proper names. The mythology Tibetan legend has

woven round the mountain is unknown to the Hindu pilgrims, and although the

number of Tibetan pilgrims circumambulating Mt. Kailasa and Manasarovar must be

many times that of Hindu pilgrims, their mythological background and the

sectarian motives are totally unrelated to each other though the general

purpose for both, as goes without saying, is the acquisition of punya,

spiritual merit. The Hindu pilgrims perform this observance in three parts:

first, they circumambulate Lake Manasarovar, and some of the more heroic among

them even take a bath in its chilly waters; the ascent to the ambiance of the

Kailasa Mountain proper begins immediately at the completion of the pradaksina

of the Manasarovar, i.e. the latter's starting point to which the pilgrims

return after this first circumambulation, is situated right at the foot of the

mountain. The circumambulation of Mount Kailasa takes about three days, that of

Manasarovar a day and a half, so the total pradaksina lasts four and a half

days. On the other side of Mount Kailasa there is another lake only slightly

smaller than Manasarovar; it is called Rakkastal by the Hindu pilgrims, and I

think it is a local Kumaoni variety of Raksastala, 'lake of the raksasas' or

demons; the pilgrims do not go near that lake, as its water is thought to be

inauspicious (hence the name?); they only cast a glance bandani nazar,' the

glance of veneration', and fold their hands; they are advised not to look at it

more often than just that one instant.

There

is no built-in theory, in tantric written tradition or in tantric oral lore,

which would establish a hierarchy of thematic importance: these decisions seem

to be left to the individual tantric. The scholar, I believe, cannot do much

more than rely on some sort of intuition by analogy: in most Indian religious

traditions there is such a hierarchy in the gamut of religious exercise

(Sadhana). Meditation first, belief in the theological framework with the

devotional (bhakti) schools this might stand first then ancillary exercises,

then perhaps charity, then study and reading. The Upanisad enjoins 'listening,

cogitating, meditating' srotavyam mantavyam nididhyasitavyam in this order, and

the general under-standing is that 'listening' is the least important,

'meditation' the most important step. It is by no means certain that this

orthodox hierarchy holds for tantrism. Ritual of all sorts seems so much more

important in tantrism than it does in non-tantric literature of the same level

of sophistication, that it seems quite possible that tantric masters did regard

activities like pilgrimage and circum-ambulation to be as nuclear to the

process as, say, deep meditation. If the proportion of textual injunction can

be a guide, these activities, which may be regarded at the most as accessories

to the religious life, by non-tantrics, have not been given any shorter shrift

than meditation proper. Just how central these activities are to the practising

and succeeding tantric we are in no position to say; yet, we cannot omit them

in a survey of the tantric tradition just because most modernistically oriented

or 'philosophically' inclined students and votaries of a religion may regard

them as marginal, or even inferior, pursuits.

There

is no built-in theory, in tantric written tradition or in tantric oral lore,

which would establish a hierarchy of thematic importance: these decisions seem

to be left to the individual tantric. The scholar, I believe, cannot do much

more than rely on some sort of intuition by analogy: in most Indian religious

traditions there is such a hierarchy in the gamut of religious exercise

(Sadhana). Meditation first, belief in the theological framework with the

devotional (bhakti) schools this might stand first then ancillary exercises,

then perhaps charity, then study and reading. The Upanisad enjoins 'listening,

cogitating, meditating' srotavyam mantavyam nididhyasitavyam in this order, and

the general under-standing is that 'listening' is the least important,

'meditation' the most important step. It is by no means certain that this

orthodox hierarchy holds for tantrism. Ritual of all sorts seems so much more

important in tantrism than it does in non-tantric literature of the same level

of sophistication, that it seems quite possible that tantric masters did regard

activities like pilgrimage and circum-ambulation to be as nuclear to the

process as, say, deep meditation. If the proportion of textual injunction can

be a guide, these activities, which may be regarded at the most as accessories

to the religious life, by non-tantrics, have not been given any shorter shrift

than meditation proper. Just how central these activities are to the practising

and succeeding tantric we are in no position to say; yet, we cannot omit them

in a survey of the tantric tradition just because most modernistically oriented

or 'philosophically' inclined students and votaries of a religion may regard

them as marginal, or even inferior, pursuits.

Writer Name: Agehananda Bharati

,+Late+19th+early+20th+Century,+Dhodeydrag+Gonpa,+Thimphu,+Bhutan.jpg) The

most important myth of tantric relevance is, then, no doubt, the story of

Daksa's sacrifice; it is told, in many minor and major variations, in all the

Puranas, and in the Epic. It is imperative to pursue this particular myth in

some detail; valuable information about its development has been furnished by

D. C. Sircar. In the tantric tradition, a centre of pilgrimage is called a

`pitha', a 'scat' of the goddess; tantric literature rarely uses the more

general word `tirtha'; probably the distinction itself depends on the

mythological relevance of the centre: shrines of the goddess are pithas,

sanctuaries of gods, or mixed shrines (i.e. where a god and a goddess are

worshipped), are called tirthas just as non-tantric worshippers would call

them. Pitha' seems to be a purely tantric term in the first place, although it

has gained currency in other, not necessarily religious, contexts in the last

two centuries; thus, several colleges teaching classical subjects in the Indian

tradition are called pithas, quite literally `seats of learning', as for instance

the Kashi Vidya pitha, one of the best institutes of higher education at

Banaras.

The

most important myth of tantric relevance is, then, no doubt, the story of

Daksa's sacrifice; it is told, in many minor and major variations, in all the

Puranas, and in the Epic. It is imperative to pursue this particular myth in

some detail; valuable information about its development has been furnished by

D. C. Sircar. In the tantric tradition, a centre of pilgrimage is called a

`pitha', a 'scat' of the goddess; tantric literature rarely uses the more

general word `tirtha'; probably the distinction itself depends on the

mythological relevance of the centre: shrines of the goddess are pithas,

sanctuaries of gods, or mixed shrines (i.e. where a god and a goddess are

worshipped), are called tirthas just as non-tantric worshippers would call

them. Pitha' seems to be a purely tantric term in the first place, although it

has gained currency in other, not necessarily religious, contexts in the last

two centuries; thus, several colleges teaching classical subjects in the Indian

tradition are called pithas, quite literally `seats of learning', as for instance

the Kashi Vidya pitha, one of the best institutes of higher education at

Banaras.  The

same tradition is followed by the Kalika Purana (ch. 64, 43-5), which calls

them (1) Odra, 'seat of the goddess Katyayani and the god jagannatha, (2)

Jalasaila, seat of the goddess Candi and the god Mahadeva, (3) Puma or

Purnasaila, seat of the goddess Purnesvari and the god Mahanatha, and finally

(4) Kamarupa, seat of the deities Kamesvari and Kamesvara. These four 'pithas'

are allocated to the four directions, but this is pure theory, and stands in

accordance with the tradition to allocate every ritualistic locale to a

direction of the compass, and hence to group them either in fours or in tens,

sometimes in groups of eight (i.e. omitting the zenith and the nadir). In

geographical reality, however, the distribution of the four main pithas is very

irregular indeed: Oddiyana, in the Swat Valley, is the only far-western site

Kamarupa and possibly Purnagiri are in the extreme east and Jalandhara again in

the middle north-west (Panjab). None of the four pit has is situated in the

south, in spite of the fact that the Kerala region has a strong Salta and

tantric element in its culture; in some form or another Sakti is the tutelary

deity of Kerala." I shall now present a token topography of tantric

sanctuaries.

The

same tradition is followed by the Kalika Purana (ch. 64, 43-5), which calls

them (1) Odra, 'seat of the goddess Katyayani and the god jagannatha, (2)

Jalasaila, seat of the goddess Candi and the god Mahadeva, (3) Puma or

Purnasaila, seat of the goddess Purnesvari and the god Mahanatha, and finally

(4) Kamarupa, seat of the deities Kamesvari and Kamesvara. These four 'pithas'

are allocated to the four directions, but this is pure theory, and stands in

accordance with the tradition to allocate every ritualistic locale to a

direction of the compass, and hence to group them either in fours or in tens,

sometimes in groups of eight (i.e. omitting the zenith and the nadir). In

geographical reality, however, the distribution of the four main pithas is very

irregular indeed: Oddiyana, in the Swat Valley, is the only far-western site

Kamarupa and possibly Purnagiri are in the extreme east and Jalandhara again in

the middle north-west (Panjab). None of the four pit has is situated in the

south, in spite of the fact that the Kerala region has a strong Salta and

tantric element in its culture; in some form or another Sakti is the tutelary

deity of Kerala." I shall now present a token topography of tantric

sanctuaries.  The

Mantramahodadhi has a section entitled `the nyasa of the pit has

(pitha-nyasa-kathanam). Literally, nyasa is the process of charging a part of

the body, or any organ of another living body, with a specified power through

touch. For instance, by placing the fire-mudra on the heart-region uttering the

fire-mantra 'ram', the adept's heart is made into the cosmic fire; and by

meditating on a specific pitha with the mantra of its presiding Sakti', the

very region (for instance the heart, or the navel, or the throat) wherein the

Sakti is thus visualized is hypostasized or trans-substantiated, into that

pitha. The tantric formulation would be: Meditating on the pilgrim-centre

through visualizing its presiding deity in the prescribed manner, the locus of

concentration in the yogi's body is charged with the spiritual efficacy of that

very place. With the Buddhist tantrics, the pattern is transparent even on a

purely doctrinal basis for no `place of pilgrimage' exist in an ontological

sense.

The

Mantramahodadhi has a section entitled `the nyasa of the pit has

(pitha-nyasa-kathanam). Literally, nyasa is the process of charging a part of

the body, or any organ of another living body, with a specified power through

touch. For instance, by placing the fire-mudra on the heart-region uttering the

fire-mantra 'ram', the adept's heart is made into the cosmic fire; and by

meditating on a specific pitha with the mantra of its presiding Sakti', the

very region (for instance the heart, or the navel, or the throat) wherein the

Sakti is thus visualized is hypostasized or trans-substantiated, into that

pitha. The tantric formulation would be: Meditating on the pilgrim-centre

through visualizing its presiding deity in the prescribed manner, the locus of

concentration in the yogi's body is charged with the spiritual efficacy of that

very place. With the Buddhist tantrics, the pattern is transparent even on a

purely doctrinal basis for no `place of pilgrimage' exist in an ontological

sense.  In a

treatment of non-tantric pilgrimage, the circumambulation-pattern which now

follows would perhaps not have to be included. However, in tantrism it is so

much a part of the process of pilgrimage that it must form the concluding, if

not the most important, section of this chapter.

In a

treatment of non-tantric pilgrimage, the circumambulation-pattern which now

follows would perhaps not have to be included. However, in tantrism it is so

much a part of the process of pilgrimage that it must form the concluding, if

not the most important, section of this chapter.  The

next two verses are captioned 'the greatness of pradaksina for Siva', and they

run 'he who has performed formal worship and who does not do pradaksina for Sambhu

(Siva), his worship is fruitless, and the worshipper is a cheat (dambhika);

(but) he who performs just only this one correct pradaksina with devotion (to Siva),

all worship has been done by such a man, and he is a true devotee of Siva'.

The

next two verses are captioned 'the greatness of pradaksina for Siva', and they

run 'he who has performed formal worship and who does not do pradaksina for Sambhu

(Siva), his worship is fruitless, and the worshipper is a cheat (dambhika);

(but) he who performs just only this one correct pradaksina with devotion (to Siva),

all worship has been done by such a man, and he is a true devotee of Siva'.  There

is no built-in theory, in tantric written tradition or in tantric oral lore,

which would establish a hierarchy of thematic importance: these decisions seem

to be left to the individual tantric. The scholar, I believe, cannot do much

more than rely on some sort of intuition by analogy: in most Indian religious

traditions there is such a hierarchy in the gamut of religious exercise

(Sadhana). Meditation first, belief in the theological framework with the

devotional (bhakti) schools this might stand first then ancillary exercises,

then perhaps charity, then study and reading. The Upanisad enjoins 'listening,

cogitating, meditating' srotavyam mantavyam nididhyasitavyam in this order, and

the general under-standing is that 'listening' is the least important,

'meditation' the most important step. It is by no means certain that this

orthodox hierarchy holds for tantrism. Ritual of all sorts seems so much more

important in tantrism than it does in non-tantric literature of the same level

of sophistication, that it seems quite possible that tantric masters did regard

activities like pilgrimage and circum-ambulation to be as nuclear to the

process as, say, deep meditation. If the proportion of textual injunction can

be a guide, these activities, which may be regarded at the most as accessories

to the religious life, by non-tantrics, have not been given any shorter shrift

than meditation proper. Just how central these activities are to the practising

and succeeding tantric we are in no position to say; yet, we cannot omit them

in a survey of the tantric tradition just because most modernistically oriented

or 'philosophically' inclined students and votaries of a religion may regard

them as marginal, or even inferior, pursuits.

There

is no built-in theory, in tantric written tradition or in tantric oral lore,

which would establish a hierarchy of thematic importance: these decisions seem

to be left to the individual tantric. The scholar, I believe, cannot do much

more than rely on some sort of intuition by analogy: in most Indian religious

traditions there is such a hierarchy in the gamut of religious exercise

(Sadhana). Meditation first, belief in the theological framework with the

devotional (bhakti) schools this might stand first then ancillary exercises,

then perhaps charity, then study and reading. The Upanisad enjoins 'listening,

cogitating, meditating' srotavyam mantavyam nididhyasitavyam in this order, and

the general under-standing is that 'listening' is the least important,

'meditation' the most important step. It is by no means certain that this

orthodox hierarchy holds for tantrism. Ritual of all sorts seems so much more

important in tantrism than it does in non-tantric literature of the same level

of sophistication, that it seems quite possible that tantric masters did regard

activities like pilgrimage and circum-ambulation to be as nuclear to the

process as, say, deep meditation. If the proportion of textual injunction can

be a guide, these activities, which may be regarded at the most as accessories

to the religious life, by non-tantrics, have not been given any shorter shrift

than meditation proper. Just how central these activities are to the practising

and succeeding tantric we are in no position to say; yet, we cannot omit them

in a survey of the tantric tradition just because most modernistically oriented

or 'philosophically' inclined students and votaries of a religion may regard

them as marginal, or even inferior, pursuits.

0 Response to "Pilgrimage"

Post a Comment