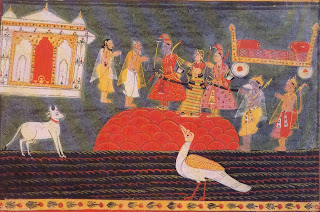

13. Illustration from a Ramayana Series:

Rama Visits Bharadvaja’s Hermitage

An

inscription on the back in Hindi states that after destroying Ravana, Rama

stopped at the hermitage of Bharadvaja, where, with his entire army, he

accepted the sage's hospitality (see Appendix).

The

picture shows Rama and his entourage being received by the sage and his

assistant. Behind Rama stand his wife, Sita, and his brother Lakshmana. They

stand as if on a pedestal on elevated ground painted in bright red. Behind them

and at a lower level are two animal-headed figures. The one with the simian head

is Hanuman, and the one with the bear's head Angada. Beyond stands the chariot

that brought them to the hermitage, which is represented by a small pavilion

behind the two sages. In the foreground is a rectangular strip of water

representing a river. A waterbird and a cow stand in the water and watch the

welcoming ceremony.

It

is remarkable how a simple meeting has been visually narrated with lively drama

through a spartan, unpretentious composition that uses few so-called pictorial

devices. The postures and gestures are ritualistically stylized, and spatial

perspective was eliminated altogether to convey a sense of timelessness.

14. Rama s Court

An

inscription in Hindi in the Devanagari script on the back (see Appendix) gives

a precise description of the picture. It informs us that after killing Ravana,

Rama has returned home to rule. He is attended by his brothers, Bharata,

Satrughna, and Lakshmana, and accompanied by Hanuman, Angada, and Sugriva. The

numeral 7 indicates that this is picture number seven of a series, which may

well be that of the ten avatars. Rama is the seventh among the ten conventional

avatars of Vishnu.

In

this formal composition Rama and Sita receive homage from Hanuman, who stands

with his club under his right arm, Angada with the bear face, and Sugriva,

another simian. Rama holds his principal attributes, the bow and the arrow. The

three brothers stand behind, and one uses the flywhisk. Characteristically,

Rama has a dark complexion, whereas his three siblings are fair.

At

least two pictures and a mural with the same subject and similar compositions

have been attributed by Archer (1973, 2: 60, figs. 30-31, 2; 61, fig. 33) to

Chamba. The two pictures are dated by him to about 1765— 70, while the mural is

from about 1840. In all three Rama and Sita are seated similarly on a low seat

and are supported by bolsters. Sita sits in an identical position in the two

eighteenth-century pictures and the Green painting. Hanuman appears in two of

the pictures illustrated by Archer and in the, Green picture. The Green

picture, however, has more figures and is a larger and more elegant composition

than the others. In any event, clearly the theme was especially popular with

patrons in Chamba, where Rama was a state deity.

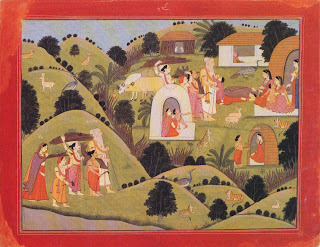

15. Hermitage of Valmiki

A

long Sanskrit text passage in Devanagari characters on the back describes the

idyllic nature of the hermitage (asrama) of Valmiki, the author of the epic

Ramayana. The verses (numbered nine to fifteen) do not appear to be from the

Ramayana, however. They tell us how in the hermitage the lions and the tigers

coexist with the cows, the cat with the mouse, and the snake with the peacock

as well as how the deer roam about without fear and how the place is inhabited

by Valmiki and other ascetics, their auspicious spouses, and sons. The number

of the folio given both on the front and back is 19. Such a low number for a

scene that occurs in the last book of the Ramayana also indicates that this

series may have belonged to another text. This possibility is strengthened by

the fact that in the painting the hermitage is placed in a hilly region, bin in

the Ramayana it is situated in the plains.

In

the picture both Valmiki and Sita are identified by labels over their heads.

Three different incidents are included in the composition, following the

traditional Indian preference for continuous narration. On the left a group led

by the bearded Valmiki approaches the hermitage. The group includes three

companions of the sage, all of whom carry wood. Sita brings up the rear.

Her

bulging waistline clearly indicates that she is pregnant. In center stage is

the same group, and now Sita, prostrating herself, pays her respects to the

wives of the sages. Then, within an oval, reed hut on the lower right, a seated

Sita is given a plate of food. Presumably she was isolated because of her

condition and did not eat with the others. Within a protective wooden fence, in

addition to small oval huts for individual families, the artist has included

the kitchen, which is a large rectangular structure, and a cow shed with two

calves inside. Predatory cats, deer, hare, cows, and peacocks rest or roam

about in peaceful coexistence, as described in the text.

The

picture is a typical example of the Kangra idiom of the early nineteenth

century. It may have been painted by an artist belonging to the family of Godhu

(fl. c. 1775), who had moved to Kangra from Chamba and became attached to the

court of Raja Samsar Chand (r. 1775-1823). According to V. C. Ohri (personal

communication), it belongs to a series known as the Nadaun Ramayana, as it

emerged from the Nadaun principality, one leaf of which is in the Himachal

State Museum, Shimla.

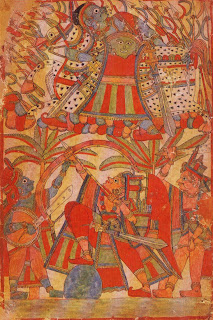

16. Illustration from a Ramayana Series (?):

Battle Scene

This

dramatic picture is in a style that appears to have been restricted to the town

of Paithan in Maharashtra. Large numbers of paintings of themes from both the

Mahabharata and the Ramayana have survived. Although the exact identification

of this example is not known, it is very likely an illustration from the

Ramayana. One cannot even be certain that the archer standing on the ground

with his right foot firmly placed on a boulder and accompanied by two

companions is shooting at the figure riding a horse above. Is the horseman on

higher ground, or is he flying through the sky? If he is the target, then he

isn't doing too badly, for it appears the arrows have missed him. Neither is it

clear what is attached to these arrows. Could the horseman represent Meghanada,

who fought with Lakshmana from behind the clouds?

Whatever

the exact subject of the picture, it is a characteristic example of the

so-called Paithan style. Although stylized, the figures have a heroic stature

and are striking for their strong animation and boldly imaginative forms.

Indeed, they are strongly reminiscent of the puppets that are still used by traditional

storytellers in parts of Maharashtra and neighboring Karnataka. In some ways

the forms are also strangely reminiscent of figures in Mayan art of the New

World.

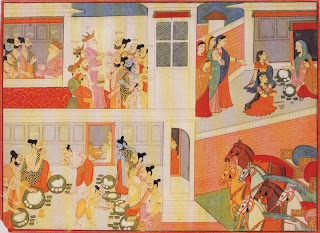

17. Illustration from a Mahabharata Series:

The Pandavas in Drupad's Court

The

principal figures in the painting are identified by their names added above

their heads in Devanagari script. The composition is clearly divided into four

segments by architectural devices, as one encounters in the sectional view of a

dollhouse. At least four if not five events are depicted, but their sequence is

not clear. All the incidents are front the Book of Virata (or the Virataparva)

of the Mahabharata, probably just before the Pandavas, who have been living

incognito at the court of King Drupad of Virata, reveal themselves and take

leave at the end of their term of exile.

In the

upper left composition we see Drupad conversing with the five brothers Yudhisthira,

Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula, and Sahadeva once inside the palace and again on a

terrace. In the room below, the brothers are being fed. At the upper right

Kunti, their mother, and Draupadi, their common wife and the daughter of

Drupad, are first being led to their meal and are then being served. In the

fourth segment six pairs of horses and three visible chariots are waiting to

take the group back to their kingdom.

Another

painting from the same series depicting Abhimanyu in the battlefield is in the

collection of the Himachal State Museum, Shimla (V. C. Ohri, personal communication).

Stylistically both pictures are close to Bhagavatapurana and Ramayana paintings

rendered in a Kangra workshop of the last quarter of the eighteenth century (cf

Goswamy & Fischer, pp. 340, no. 143: Randhawa 1660). Following Goswamy and

Fischer, one might ascribe this painting to "a Master of the First

Generation after Nainsukh." In other words, the Kangra workshop was probably

headed by a member of this Pahari master's family.

18. The Goddess Durga Slays a Titan

Individual

pictures representing the cosmic goddess Durga slaying titans were popular with

patrons in the states of Bundi and Kota during the eighteenth century. Usually

in such pictures an elaborate setting is eschewed in favor of a direct and

dramatic combat between the goddess and one or more titans. In this simple

composition, for instance, only two curved segments at the two upper corners

indicate a horizon and a sky. The figures are represented against a

monochromatic background, which accentuates the forms and enhances the sense of

movement.

The

exact identification of the goddess's protagonist is not possible. He conforms

to a type and is not distinguished by individualizing iconographic features.

The goddess is eight-armed and rides a tiger rather than the more common lion.

Instead of a saddle a soft cushion of lotus flowers serves as her seat. She

does not appear to be very bellicose but sits on her haunches like a demure

lady. What is interesting is that she has acquired a new weapon in the form of

a dagger known as a katar and popular in Mughal India (second hand from the top

on her proper left). The blue-black figure at the left margin brandishing a.

dagger is very likely one of the goddess's companions, perhaps even the

terrifying Kali. However, the sex of the figure is not clear, and it may be a

male rather than a female. Behind Durga stands a young ascetic holding a

trident in his right hand and what appears to be a flask and a cup in the left.

Interestingly, both standing figures are wearing wooden slippers. The most

impressive creature in the group is the tiger, which attacks the titan with

customary ferocity, in strong contrast to Durga's serenity.

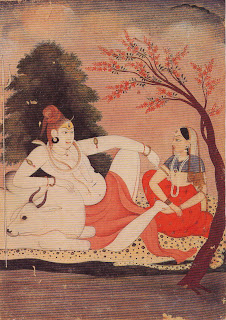

19. Siva and Parvati

Siva

and Parvati sit in a relaxed mood on his leopard-skin shawl spread on the

ground. He reclines against his bull, using it as a bolster, and strikes a

posture that is very familiar in India. In fact, but for his third eye and the

snake around his neck, Siva could be a prosperous human or a religious

personage enjoying an afternoon off. Like a dutiful wife or a favorite female

disciple, Parvati supports his right foot. A flowering tree bends over Parvati

to form a charming canopy, while Siva's glistening white complexion is strongly

contrasted against the dark and dense mass of foliage behind him. Although the

theme was very popular among Pahari artists, few representations are as elegant

and enchanting as this composition.

The

closest parallel for Siva's head can be seen in Basohli-style paintings of

about 1725 (cf. Khandalavala 1958, study supplement, no. 31), while Parvati's

figure is remarkably like a Gujari Ragini attributed by Archer (i973, 2: 254,

110. 32) to Kulu and about 1765-70. The use of the beetle thorax casing for

Siva's earring would also indicate a Basohli origin. Most scholars who have

seen the picture are divided between a Guler or a Chamba provenance. Although

it is difficult to be precise about the origin of the Green picture, it can be

dated to around 1750 with greater certainty. The manner in which the trees are

painted, the soft coloring, and the mode of rendering the sky are not

encountered in Basohli paintings prior to 1730 and, in fact, anticipate the

more painterly treatment of nature seen in Pahari pictures from about 1750.

There

can be little doubt that the unknown artist was highily accomplished. He was an

excellent draftsman, and his sense of coloring and skill in composition are

admirable. The picture displays his sure vivacity in handling forms and an

unfailing sense of style. If the picture was rendered in Guler or Chamba, the

artist may have belonged to the school, if not family, of Pandit Seu of Guler,

a family that is regarded as ushering in a new direction in Pahari painting and

may have been influenced by the Basohli mode.

20. Holy Family on the March

This

picture depicts Siva and his family coming down the mountains. The group is led

by Siva's simian attendant, Nandisvara, who carries a bundle on his head and a

drum (a mridangam) hanging from his right shoulder. Siva, distinguished by his

leopard skin shawl, the trident, and the snake, waits gallantly to help Parvati

negotiate the difficult terrain. She has the multi headed Karttikeya held

against her left shoulder. Above them Ganesa looks very comfortable on Siva's

bull. Karttikeya's peacock too hitches a ride, while Ganesa's rat ambles along

in front of the bull. The rear is brought up by the goddess's saddled tiger.

This

picture depicts Siva and his family coming down the mountains. The group is led

by Siva's simian attendant, Nandisvara, who carries a bundle on his head and a

drum (a mridangam) hanging from his right shoulder. Siva, distinguished by his

leopard skin shawl, the trident, and the snake, waits gallantly to help Parvati

negotiate the difficult terrain. She has the multi headed Karttikeya held

against her left shoulder. Above them Ganesa looks very comfortable on Siva's

bull. Karttikeya's peacock too hitches a ride, while Ganesa's rat ambles along

in front of the bull. The rear is brought up by the goddess's saddled tiger.

An

almost identical composition of roughly the same date is in the Bharat Kala

Bhavan, Varanasi (Kramrisch 1981, pp. 206-7, no. P-4o). In her catalogue (p.

205) Kramrisch has noted that "to this day, the people of the Himalayas

believe that every twelve years Siva and Parvati descend from their residence

on Mount Kailasa and come down to earth. Taking their children and some of

their possessions with them they go from place to place to check on all of

creation, for which Siva is responsible." It may be remarked further that

the mountain-dwelling shepherds known as gaddis or gujars lead a seminomadic

existence and move down from the mountains every year. And, although Siva's

original habitat is Mount Kailasa, he is also known to lead a nomadic life.

Therefore, it is not difficult to understand why the subject would be popular

with the artists in the Hill States.

Because

of their strong similarities, it is very likely that the two pictures are based

on the same drawing or pounce. Pounces were made for popular compositions and

kept in a family of artists to be used when necessary. If indeed the Green and

the Varanasi pictures are based on the same pounce, then the two renderings may

be by two different artists, but of the same family. The shapes of the. rocks

as well as the trees are more schematized in the Varanasi picture. In the Green

version Nandisvara holds his stick jauntily over his left shoulder, and great

sensitivity is expressed in the manner in which Siva holds Parvati's hand. The

bull is drawn more realistically than in the other version, and the saddle

cloth is a patchwork quilt rather than a carpet. In both, however, the rat has

the proportions and shape of a dog. For other versions of the theme, see

Panthey and Khandalavala.

Writer Name: Pratapaditya Pal

This

picture depicts Siva and his family coming down the mountains. The group is led

by Siva's simian attendant, Nandisvara, who carries a bundle on his head and a

drum (a mridangam) hanging from his right shoulder. Siva, distinguished by his

leopard skin shawl, the trident, and the snake, waits gallantly to help Parvati

negotiate the difficult terrain. She has the multi headed Karttikeya held

against her left shoulder. Above them Ganesa looks very comfortable on Siva's

bull. Karttikeya's peacock too hitches a ride, while Ganesa's rat ambles along

in front of the bull. The rear is brought up by the goddess's saddled tiger.

This

picture depicts Siva and his family coming down the mountains. The group is led

by Siva's simian attendant, Nandisvara, who carries a bundle on his head and a

drum (a mridangam) hanging from his right shoulder. Siva, distinguished by his

leopard skin shawl, the trident, and the snake, waits gallantly to help Parvati

negotiate the difficult terrain. She has the multi headed Karttikeya held

against her left shoulder. Above them Ganesa looks very comfortable on Siva's

bull. Karttikeya's peacock too hitches a ride, while Ganesa's rat ambles along

in front of the bull. The rear is brought up by the goddess's saddled tiger.

0 Response to "About on The Divine World"

Post a Comment