The

principal centre of Pahari painting was the Kangra Valley where the artists

worked under the patronage of the Hill Rajas of Guler, Kangra and Nurpur. From

here the artists migrated to the neighbouring States of Mandl, Suket, Kulu,

Tehri and Garhwal in the cast and Basohli and Chamba in the north. The art of

these States was but an off-shoot of the art of Kangra and the most appropriate

name for this version of Rajput art is the "Kangra Valley School of

Painting".

The

principal centre of Pahari painting was the Kangra Valley where the artists

worked under the patronage of the Hill Rajas of Guler, Kangra and Nurpur. From

here the artists migrated to the neighbouring States of Mandl, Suket, Kulu,

Tehri and Garhwal in the cast and Basohli and Chamba in the north. The art of

these States was but an off-shoot of the art of Kangra and the most appropriate

name for this version of Rajput art is the "Kangra Valley School of

Painting".

Specimens

of early paintings in the Basohli style can be found in all the Punjab Hill

States. They are simple works, full of strength and primitive vitality. The

pattern is rugged and domineering, and the lines and colours are bold and

enduring. The hill painter selected themes which he could handle with masculine

directness, without apology or prudery. He worked with fearless passion,

imparting 10 his work energy and power which is in great contrast with the

nervous grace of later creations. The artist attained a maximum of expression

with the minimum of means. The vibrant colours of Basohli paintings are

enchanting.

The

main centres of Kangra painting were Guler, Basohli, Chamba, Nurpur, Bilaspur

and Kangra. Guler, and Nurpur are near the plains and their Rajas came into

early contact with the Mughal emperors.

Of the

Hill States, Guler has the longest tradition in the art of painting. It has

been established that during the rule of Dalip Singh (A.D. 1695-1743) artists

were working at Haripur-Guler. Portraits of Dalip Singh exist and these can

hardly be later than 1720. There are a number of portraits of his eldest son,

Bishan Singh, which can be dated to about 1730. Bishan Singh died during the

lifetime of his father and in 1743 his younger brother Govardhan Chand became

the Raja of Guler. Govardhan Chand was a patron of art and a large number of

his portraits which were formerly in the collection of Raja Baldev Singh are

now in Chandigarh Museum. We reproduce a painting of Govardhan Chand listening

to music, which was in the collection of Raja Baldev Singh and is now in

Chandigarh Museum.

The

Raja is seated on a terrace listening to the music of drums and pipes. Terraces

of this nature can be seen in the Haripur-Guler Fort overlooking the Ranganga.

It is a key painting which marks the transition of the Mughal into the Kangra

style. Describing this painting, J. C. French observes: "The Raja is

listening to music, and the air of gentle reverie is well expressed. The pose

of the individual figures and the balance of the whole is admirable. In this

respect it resembles the finest of the Mogul paintings, but it has a delicacy

and a spirituality of feeling to which the Mogul art never attains. The

coloring of Kangra pictures of this period is extraordinarily delicate. The

Kangra artist had the colours of the dawn and the rainbow on his

palette."The role of Guler in the evolution of the Kangra style is thus

summed up by Dr. Archer:

The

Raja is seated on a terrace listening to the music of drums and pipes. Terraces

of this nature can be seen in the Haripur-Guler Fort overlooking the Ranganga.

It is a key painting which marks the transition of the Mughal into the Kangra

style. Describing this painting, J. C. French observes: "The Raja is

listening to music, and the air of gentle reverie is well expressed. The pose

of the individual figures and the balance of the whole is admirable. In this

respect it resembles the finest of the Mogul paintings, but it has a delicacy

and a spirituality of feeling to which the Mogul art never attains. The

coloring of Kangra pictures of this period is extraordinarily delicate. The

Kangra artist had the colours of the dawn and the rainbow on his

palette."The role of Guler in the evolution of the Kangra style is thus

summed up by Dr. Archer:

"The

State of Guler played a decisive part in the development of Pahari painting in

the eighteenth century. Not only did it develop a local art of the greatest

delicacy and charm, but the final version of this Guler style was taken to

Kangra in about 1780, thus becoming the `Kangra' style itself. Guler is not

merely one of thirty-eight small centres of Pahari art. It is the originator

and breeder of the greatest style in all the Punjab hills." Subsequent

research has fully confirmed Dr. Archer's thesis, and if any place can be

called the birth place of Kangra painting, it is Guler.

Research

which has been carried from 1952 onwards has proved that the paintings in early

Guler style were by the artists Manaku and Nainsukh. The sons of these artists

and the grandsons of Nainsukh worked at Guler, Basohli, Chamba and other places

and are responsible for the finest paintings.

The

greatest patron of painting in the Punjab hills was Maharaja Sansar Chand. He

was born in 1765 at Bijapur, a village in Palampur tehsil. In 1786, he occupied

the Kangra Fort and became the most powerful Raja of the Punjab hills. In 1794,

he defeated Raja Raj Singh of Chamba and annexed a part of his territory. Later

on, he defeated the Rajas of Sirmur, Mandl and Suket. Raja Prakash Chand of

Guler became his vassal.

In

1809, Sansar Chand employed a European adventurer, 0' Brien, who established a

factory of small arms and raised a disciplined force of 1400 men for him. In seelo

Brien waving a fly-whisk over Sansar Chand. It is a very fine portrait by one

of the Guler artists who had migrated to Tira-Sujanpur. The green background

with dashes of red in the horizon is typical of the work of these artists. The

character of Sansar Chand, proud and sensitive, is well brought out in this

painting.

Kangra

paintings under the patronage of Sansar Chand were painted at Alampur,

Tira-Sujanpur and Nadaun, all on the banks of the Beas. Very little painting,

if at all, was done at Kangra proper which remained under Mughal occupation

till 1786 and Sikh occupation from A.D. 1810 to 1846.

Little

has been written about Nurpur, an important centre of Kangra painting. Raja Bas

Dev (A.D. 1580-1613) came in conflict with the Mughals during the reign of

Akbar. Jagat Singh (A.D. 1619-1646), however, entered the service of Jahangir

and must have come in contact with the work of Mughal painters. A portrait of

Jagat Singh in Basohli style is in the collection of Chandigarh Museum, and

there is every likelihood that this style may have originated as a parallel

development at Nurpur apart from Basohli. Rajrup Singh (A.D. 1646-1661) was

also in the employ of Aurangzeb. Some paintings ascribed to the reign of

Prithvi Singh (A.D. 1735-1789) are extant. Most of them belong to the reign of

Bir Singh (A.D. 1789-1846), a contemporary of Prakash Chand and Sansar Chand.

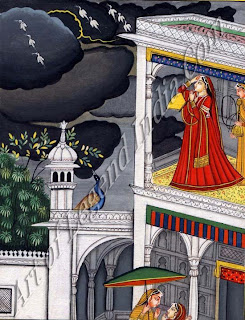

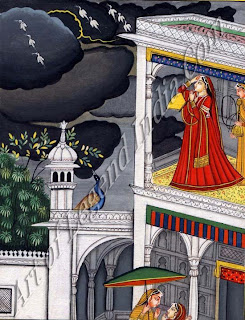

"Sensitive,

reticent and tender, it perfectly reflects the self-control and sweet serenity

of Indian life, and the definitely theocratic and aristocratic organisation of

Indian society. It lands itself to the utterance of serene passion and the

expression of unmixed emotions!" This description of Rajput painting by Coomaraswamy

is particularly relevant to the art of the lovely valley of Kangra. The romance

of the Epics and the Puranas were here given a new life in the voluptuous line

and colour, the Krishna-Lila with all its exotic symbolism was reenacted by the

painter's brush, the Shiva-Parvati lore was invested with fresh colour and the

lyrics of Keshav Das were given a new expression.

The art

of the Kangra Valley acquires deep meaning if viewed in its cultural

perspective. The symbolism conveys to us a sense of reality. The style has a

unique sense of freedom and is closely connected with the soil. There is no

self-consciousness, no studied emotions, no attitudes. It is free from the

stresses of exaggerated personality and deliberate individuation, and the

painting is nothing but music in colour. The emotions it seeks to portray are

registered with astonishing truth. The technique is "limited", and we

find the painter employing set formulas in the portrayal of features, limbs and

landscape. Yet the effect is beautiful, for the forms that evoke it are truly

vital, transcending the limitations of mere technique. It is here that lies the

greatness of Kangra art.

The

flowing and graceful curves of Kangra art form rhymes and assonances. The eye

moves with ease and comfort from one point to another enjoying delightful

rhythms and harmonies and the restful beauty of the curve.

The

flowing and graceful curves of Kangra art form rhymes and assonances. The eye

moves with ease and comfort from one point to another enjoying delightful

rhythms and harmonies and the restful beauty of the curve.

With a

change in the taste of the patrons, and in keeping with the new trends of

mysticism, lyricism was seen to enter Kangra painting. "The figures are

now more animated, the line more nervous and fluent, the resurge of physical

charm is deliberate, women are willowy and slender, their eyes very long and

curved, and the deep-dyed fingers are delicate and tapering."' Kangra art

was imbued with a subtle charm, and the delicate and refined pictures acquired

an almost feminine grace for which they were to become so well known.

The

inner vitality and natural charm of the style faded away in the early 19th

century. There was an increasing tendency towards mere ornamentation. The

energy of the artist was now directed towards superficial embellishment and

fineness of detail. The art fell into decay and died, but the artist outlived

it for a while. He was haunted by memories which he tried to paint, but the

living presence that inspired him once was no more. The patronage of the court,

too, had disappeared and though he painted, there was neither joy in his work

nor life in his creation. There was an endless repetition of cliches.

The

birth of Kangra art in the Valley about the middle of the 18th century, and its

decline in the middle of the 19th century is a strange phenomenon in the

history of Indian art. Its sudden decay is difficult to explain. The Valley is

the same with its mountains and sparkling streams of water, but where are those

men of genius? As one wanders through the ruins of Haripur, Sujanpur, and Nadaun,

one cannot help being moved by the dead splendour of the palaces; their culture

has disappeared never to return.

To turn

to the technique of Kangra painting; its chief features are delicacy of line,

brilliance of colour and minuteness of decorative detail. Like the art of

Ajanta, Kangra art is essentially an art of line. As Coomaraswamy observes,

"Vigorous archaic outline is the basis of its language." This amazing

delicacy and fineness of the line was achieved by the use of fine brushes made

from the hair of squirrels.

A

preliminary sketch in light red colour was made with the brush on brown

hand-made Sialkoti paper. This was primed with white and the surface made very

smooth. The outlines were then redrawn in brown or black. Colour was now applied,

first the background and then the figures. The outline was now redrawn and the

picture finished. Very often the colouring was done by assistants after the

master had completed the drawing.

The

Kangra painters made use of pure colours, like yellow, red and blue, and these

have retained their brilliance, even after two hundred years. Many unfinished

sketches are to be had in which the names of colours to be employed are

indicated on the sketch. Sketches were often preserved as heirlooms, and used

for fresh commissions with a few modifications.

Kangra

painting knows no perspective, but the wonderful glowing colours and delicate

line-work more than compensate for this deficiency. The human figures,

particularly of women, were mostly drawn from memory and this explains the

similarity of the female faces with gazelle-like eyes, straight noses and

rounded chins. Each artist evolved his own formula for the portrayal of faces,

and though names of artists may not be written on paintings, it is possible at

times to identify the work of individual artists. Almost all the faces are

drawn in profile. Perhaps it was easier to do so, but it may be that the

beautifully chiselled features of Kangra women are more effectively portrayed

in this manner.

Kangra

painting till recently was regarded as largely anonymous. Recent research has

revealed the names of a number of artists. Manaku and Nainsukh were artists of

outstanding ability. Kama, Nikka, Ranjha and Gaudhu, sons of Nainsukh, were

also well-known artists. A few pictures from Guler are signed by Gursahaya.

Khushala, Fattu and Purkhu are mentioned as artists in the employ of Sansar

Chand. Purkhu specialised in delicate paintings in transparent tones and

subdued colour. His son, Ramdayal, who is said to have inherited much of his

father's talent, is also mentioned. Nikka worked at Chamba during the rule of

Raja Raj Singh. His sons Chhajju and Harkhu worked for Raja Jeet Singh.

The

central theme of Kangra painting is love, and its sentiments are expressed in a

lyrical style full of rhythm, grace and beauty. As Coomaraswamy states,

"What Chinese art achieved for landscape is here accomplished for human

love." The recurring theme of Kangra painting, whether it portrays one of

the six seasons or modes of music, Krishna and Radha or Shiva and Parvati, is

the love of man for woman and of woman for man. To the Kangra painters the

beauty of the female body comes first and all else is secondary. It is her

charms that are reflected in the landscape of the Kangra Valley.

Dr. W.

G. Archer has rendered great service to art criticism and appreciation by

pointing out sexual symbols in Kangra painting. Whether the symbols were

consciously used or were an expression of hidden urges of the subconscious mind

is difficult to decide. Rajput society of the late 18th and early 19th

centuries was puritanical in nature. There was considerable repression of

normal emotions and it is possible that the aristocracy found a release for its

repressed desires in paintings of an erotic character.

These

love-pictures display considerable intensity of feeling and are works of real

beauty. Life in the foot-hills of the Himalayas was full of danger and

insecurity, and death lurked not only on the battle-field but also in the thick

forests that covered the area. Women were greatly relieved when their husbands

came home safely, and their meeting was all the more intense for its

uncertainty.

These

love-pictures display considerable intensity of feeling and are works of real

beauty. Life in the foot-hills of the Himalayas was full of danger and

insecurity, and death lurked not only on the battle-field but also in the thick

forests that covered the area. Women were greatly relieved when their husbands

came home safely, and their meeting was all the more intense for its

uncertainty.

We sec

a deep love of nature in Kangra painting. The landscapes are characteristic of

the lower Beas Valley. Low undulating hills crowned with umbrella-like pipal

and banyan trees, mango groves, and the farmers' homesteads hidden in clumps of

bamboo and plantain, fresh water streams brimming with the glacial waters of

the Dhauladhar, rivulets meandering through wave-like terraced fields in which

love-sick pairs of mints cranes wander all these are represented faithfully.

This landscape is suffused with love, and the intensity of the artist's

perception breaks through the world of appearances to touch the core of

reality. As Okakura says: "Fragments of nature in her decorative aspects,

clouds black with sleeping thunder, the mighty silence of pine forests, the

immovable serenity of the snow and the ethereal purity of the lotus rising out

of darkened waters, the breath of star-like plum flowers, the stains of heroic

blood on the robes of maidenhood, the tears that may be shed in his old age by

the hero, the mingled terror and pathos of war, and the waning light of some

great splendor such are the moods and symbols into which the artistic

consciousness sinks before it touches with revealing hands that mask under

which the Universal hides. Art thus becomes the moment's repose of religion, or

the instant when love steps half unconscious on her pilgrimage in search of the

Infinite, lingering in gaze on the accomplished past and dimly seen future a

dream of suggestion, nothing more fixed but a suggestion of the spirit, nothing

less noble."

Writer -

M.S. Randhawa

The

principal centre of Pahari painting was the Kangra Valley where the artists

worked under the patronage of the Hill Rajas of Guler, Kangra and Nurpur. From

here the artists migrated to the neighbouring States of Mandl, Suket, Kulu,

Tehri and Garhwal in the cast and Basohli and Chamba in the north. The art of

these States was but an off-shoot of the art of Kangra and the most appropriate

name for this version of Rajput art is the "Kangra Valley School of

Painting".

The

principal centre of Pahari painting was the Kangra Valley where the artists

worked under the patronage of the Hill Rajas of Guler, Kangra and Nurpur. From

here the artists migrated to the neighbouring States of Mandl, Suket, Kulu,

Tehri and Garhwal in the cast and Basohli and Chamba in the north. The art of

these States was but an off-shoot of the art of Kangra and the most appropriate

name for this version of Rajput art is the "Kangra Valley School of

Painting".  The

Raja is seated on a terrace listening to the music of drums and pipes. Terraces

of this nature can be seen in the Haripur-Guler Fort overlooking the Ranganga.

It is a key painting which marks the transition of the Mughal into the Kangra

style. Describing this painting, J. C. French observes: "The Raja is

listening to music, and the air of gentle reverie is well expressed. The pose

of the individual figures and the balance of the whole is admirable. In this

respect it resembles the finest of the Mogul paintings, but it has a delicacy

and a spirituality of feeling to which the Mogul art never attains. The

coloring of Kangra pictures of this period is extraordinarily delicate. The

Kangra artist had the colours of the dawn and the rainbow on his

palette."The role of Guler in the evolution of the Kangra style is thus

summed up by Dr. Archer:

The

Raja is seated on a terrace listening to the music of drums and pipes. Terraces

of this nature can be seen in the Haripur-Guler Fort overlooking the Ranganga.

It is a key painting which marks the transition of the Mughal into the Kangra

style. Describing this painting, J. C. French observes: "The Raja is

listening to music, and the air of gentle reverie is well expressed. The pose

of the individual figures and the balance of the whole is admirable. In this

respect it resembles the finest of the Mogul paintings, but it has a delicacy

and a spirituality of feeling to which the Mogul art never attains. The

coloring of Kangra pictures of this period is extraordinarily delicate. The

Kangra artist had the colours of the dawn and the rainbow on his

palette."The role of Guler in the evolution of the Kangra style is thus

summed up by Dr. Archer:  The

flowing and graceful curves of Kangra art form rhymes and assonances. The eye

moves with ease and comfort from one point to another enjoying delightful

rhythms and harmonies and the restful beauty of the curve.

The

flowing and graceful curves of Kangra art form rhymes and assonances. The eye

moves with ease and comfort from one point to another enjoying delightful

rhythms and harmonies and the restful beauty of the curve.  These

love-pictures display considerable intensity of feeling and are works of real

beauty. Life in the foot-hills of the Himalayas was full of danger and

insecurity, and death lurked not only on the battle-field but also in the thick

forests that covered the area. Women were greatly relieved when their husbands

came home safely, and their meeting was all the more intense for its

uncertainty.

These

love-pictures display considerable intensity of feeling and are works of real

beauty. Life in the foot-hills of the Himalayas was full of danger and

insecurity, and death lurked not only on the battle-field but also in the thick

forests that covered the area. Women were greatly relieved when their husbands

came home safely, and their meeting was all the more intense for its

uncertainty.

0 Response to "Patrons, Artists And Themes of Kangra Paintings"

Post a Comment