Radha

makes her debut as Krishna's chief consort in the Gitagovinda. Previously she

was known only from sporadic literary and epigraphical references, beginning in

the seventh century. Radha is absent from the major early texts in which the

life of Krishna is related: the Bhagavatapurana, Harivamsa,and

Vishnupurana. In these earlier texts, Krishna dallies with an anonymous group

of cowherdesses (gopis) rather than a favorite lover. As a result of the

exclusive emphasis accorded Radha in the Gitagovinda, her fame and popularity

grew so powerful that one sect, the Radhavallabhis founded in the sixteenth

century at Brindavan near Mathura, regarded her as supreme over Krishna and to

be the cosmic source of his divine energy.

Radha

makes her debut as Krishna's chief consort in the Gitagovinda. Previously she

was known only from sporadic literary and epigraphical references, beginning in

the seventh century. Radha is absent from the major early texts in which the

life of Krishna is related: the Bhagavatapurana, Harivamsa,and

Vishnupurana. In these earlier texts, Krishna dallies with an anonymous group

of cowherdesses (gopis) rather than a favorite lover. As a result of the

exclusive emphasis accorded Radha in the Gitagovinda, her fame and popularity

grew so powerful that one sect, the Radhavallabhis founded in the sixteenth

century at Brindavan near Mathura, regarded her as supreme over Krishna and to

be the cosmic source of his divine energy.

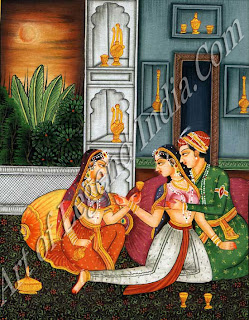

Perhaps

the most persistent theme in all of Indian art and literature is that of love,

both secular and divine. Numerous texts and myriad images are devoted to it,

including a number of the paintings in the Green collection. The divine lovers

Radha and Krishna served as the primary literary and artistic impetus. Their

popularity was such that the imagery of their romance was even borrowed for

personifying the various types of lovers long codified in Indian

literature.

The

symbolic role of love achieved its greatest prominence during the tenth through

eighteenth centuries with the widespread efflorescence of the cult of bhakti,

"literally 'participation' (of the soul in the divine)". Loving

devotion to a personal deity, especially Krishna, was considered to be the

ultimate form of religious pursuit and expression. Devotional poets and

sectarian teachers appropriated the imagery of the married cowherdess Radha's

pining for her divine paramour Krishna to express the yearning of the soul for

godhead. The romance of the divine couple was described and depicted in a wide

range of emotional situations and activities, including impassioned

intercourse.

One of

the earliest and most important of the literary works on love that is

represented in the Green collection is the Gitagovinda (Song of the herdsman),

the devotional text par excellence of the Krishna cult. Composed in Sanskrit by

the poet Jayadeva, the lyric, erotic poem describes the initial passion of

Radha and Krishna, their temporary estrangement because of Radha's jealousy

over Krishna's sharing of his love with other cowherdesses, and their ecstatic

reconciliation in Krishna's nocturnal bower of delight. Although ostensibly a

secular work, the Gitagovinda must also be regarded as a religious text owing to

its intensely devout character, its metaphorical devotional symbolism, and its

extensive adoption by Krishna devotees. Indeed, the Gitagovinda is considered a

classic example of the widespread coalescence of the sacred and the secular

within traditional Indian culture.

Radha

makes her debut as Krishna's chief consort in the Gitagovinda. Previously she

was known only from sporadic literary and epigraphical references, beginning in

the seventh century. Radha is absent from the major early texts in which the

life of Krishna is related: the Bhagavatapurana, Harivamsa,and

Vishnupurana. In these earlier texts, Krishna dallies with an anonymous group

of cowherdesses (gopis) rather than a favorite lover. As a result of the

exclusive emphasis accorded Radha in the Gitagovinda, her fame and popularity

grew so powerful that one sect, the Radhavallabhis founded in the sixteenth

century at Brindavan near Mathura, regarded her as supreme over Krishna and to

be the cosmic source of his divine energy.

Radha

makes her debut as Krishna's chief consort in the Gitagovinda. Previously she

was known only from sporadic literary and epigraphical references, beginning in

the seventh century. Radha is absent from the major early texts in which the

life of Krishna is related: the Bhagavatapurana, Harivamsa,and

Vishnupurana. In these earlier texts, Krishna dallies with an anonymous group

of cowherdesses (gopis) rather than a favorite lover. As a result of the

exclusive emphasis accorded Radha in the Gitagovinda, her fame and popularity

grew so powerful that one sect, the Radhavallabhis founded in the sixteenth

century at Brindavan near Mathura, regarded her as supreme over Krishna and to

be the cosmic source of his divine energy.

The

devotional literature and poetry composed after the Gitagovinda continued to

stress the theme of worldly love as a metaphor for the soul's search for

divinity. The romance and imagery of Krishna and Radha remained paramount and,

perhaps most significantly, became pictorially and textually interwoven with an

established literary tradition that classified generic female lovers,

translated as "heroines" or "ladies") and male lovers

(nayakas, translated as "heroes" or "lords") by romantic

situation and emotional charge. Ideal lovers had long been described in

classical Sanskrit texts on dance and eroticism, but it was not until the late

sixteenth century in the Rasikapriya (Connoisseurs' delights) of Kcsavadas (c.

1554-c. i600) that Radha and Krishna were explicitly identified as a nayika and

a nayaka.

There

are eight types of female lovers classified by Kesavadas in the Rasikapriya:

she whose beloved is subject to her, she who is alone and yearning, she who

waits by the bed, she who is separated from her beloved by a quarrel, she who

is offended, she whose beloved has gone abroad, she who has made an appointment

and is disappointed, she who goes out to meet her beloved. The poet further

subdivides each category according to various physical differences, mental

attitudes, and environmental situations. Kesavadas's correlation of Radha and

Krishna with the tradition of ideal lovers was both innovative and inspired,

and it certainly contributed to the immense popularity of the text.

Another

key distinguishing characteristic of the Rasikapriya is that it was written in

the vernacular Hindi rather than the Sanskrit of the courts, as was the

Gitagovinda. Texts classifying lovers continued to be written in Sanskrit, but

it was in Hindi that the romance of Radha and Krishna and their

personifications as ideal lovers achieved the greatest appeal. Hindi devotional

literature is exceedingly rich, and countless love poems were written after the

Rasikapriya, such as the Satsai of Bihari Lal, that are equally passionate in

their descriptions of the love of Radha and Krishna. The imagery of the divine

lovers was also adopted and used symbolically in contexts as diverse as the

Baramasa (The twelve months), a collection of poems celebrating the months of

the year and the emotional states associated with each month or climatic

season.

Numerous

other lovers were also portrayed and glorified in the art and/or the oral and

literary traditions of northern India. This was especially true in the Panjab,

an area renowned for its association with lovers. Perhaps the best known such

couple was Sohni and Mahinwal, two ill-fated lovers whose tragic tale captured

the imagination of artists and poets throughout northern India in the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Other celebrated lovers include Baz

Bahadur and Rupmati, Dhola and Marti, Sassi and Punnu, Hir and Ranjha, and the

Iranian lovers Layla and Majnun. Some may have been fictional, or at least had

their romances considerably embellished. Others were historical figures who

were portrayed in the celestial guise of Radha and Krishna, such as the

eighteenth-century ruler of Kishangarh Savant Singh and his favorite mistress,

Bani Thani.

Savant

Singh was an enlightened ruler and a great devotee of Krishna. As well as being

a renowned warrior in the grand Rajput tradition, he was a painter, musician,

and accomplished poet. Besides his love of Krishna, Savant Singh was enamored

of a beautiful courtesan and singer whose real name is unknown but who is

popularly known in the court records and Savant Singh's poems as Bani Thani,

"she who is smart and well-dressed." So great was Savant Singh's love

of both Krishna and Bani Thani that in 1757 he abdicated his throne to move

with his beloved to Brindavan, the pastoral home of Krishna, in order to devote

himself to Krishna's worship and dwell in his lord's domain. Savant Singh and

Bani Thani lived in idyllic bliss at Brindavan until his death in 1764 and hers

the following year. The passionate love of Savant Singh for both Krishna and

Bani Thani inspired the artists of Kishangarh to create a phenomenal series of

paintings portraying the king and his consort as the divine couple Krishna and

Radha.

Moreover,

apart from representations of divine or ideal lovers, the theme of love is

suggested implicitly in certain landscape painting conventions. Pairs of birds

and animals are used as metaphors for loving couples or the act of love. The

moon and secluded forest groves suggest sensual trysts in the night. Similarly,

dramatic lightening and deep, rich colors, particularly brown or blue-black,

are symbolic of ardent passion. These compositional elements all contribute to

the emotional flavor (rasa) of the paintings (Goswamy 1986a). Like the legends

of the lovers they portray, Indian paintings on the theme of romance are

evocative and capable of producing the same intense emotional response as the

inspired poetry they so eloquently illume.

Writer – Stephen Markel

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Themes of Romance"

Post a Comment