The dissolution of Mughal power

in the 18th century was matched by a similar decline at the courts of

Rajasthan. From the 1730s they were repeatedly overrun by the Marathas from the

south, who brought about a political and economic chaos that lasted until the

establishment of British suzerainty in 1818. Jaipur, which had been founded

close to Amber by the distinguished astronomer Raja Sawai Jai Singh

(1693-1743), is said to have reached depths of turpitude and intrigue

exceptional even in an age of general decadence. But painting continued under

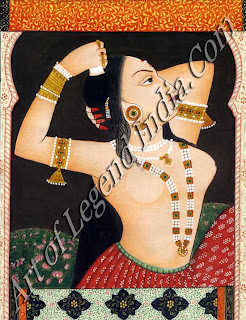

its own inherent momentum. The Jaipur artists were much influenced by the hard

contemporary style of Delhi and Lucknow. Even so, a hackneyed subject of a lady

at her toilet could be transformed into a classically Rajput image by the

accentuated outline drawing of the face and figure and the contrast of

unmodelled flesh and background areas with the detail of jewellery, textile

patterns and a flower gardefik A more ebullient late phase of Rajasthani

painting occurred at Kotah under Rao Ram Singh (1827-65), who is seen passing

in procession through a bazaar, entertained as he rides by a nautch girl

supported on his elephant's tusks If this picture lacks the kinetic force of

the earlier elephant fight, it still has much charm and panache. Already,

however, a harsh synthetic green colour is in use. During the second half of

the-19th century traditional painting either succumbed or was

radically changed by the impact of Western techniques and the sensational art

of photography.

The dissolution of Mughal power

in the 18th century was matched by a similar decline at the courts of

Rajasthan. From the 1730s they were repeatedly overrun by the Marathas from the

south, who brought about a political and economic chaos that lasted until the

establishment of British suzerainty in 1818. Jaipur, which had been founded

close to Amber by the distinguished astronomer Raja Sawai Jai Singh

(1693-1743), is said to have reached depths of turpitude and intrigue

exceptional even in an age of general decadence. But painting continued under

its own inherent momentum. The Jaipur artists were much influenced by the hard

contemporary style of Delhi and Lucknow. Even so, a hackneyed subject of a lady

at her toilet could be transformed into a classically Rajput image by the

accentuated outline drawing of the face and figure and the contrast of

unmodelled flesh and background areas with the detail of jewellery, textile

patterns and a flower gardefik A more ebullient late phase of Rajasthani

painting occurred at Kotah under Rao Ram Singh (1827-65), who is seen passing

in procession through a bazaar, entertained as he rides by a nautch girl

supported on his elephant's tusks If this picture lacks the kinetic force of

the earlier elephant fight, it still has much charm and panache. Already,

however, a harsh synthetic green colour is in use. During the second half of

the-19th century traditional painting either succumbed or was

radically changed by the impact of Western techniques and the sensational art

of photography.

By the 15705 Akbar had

succeeded in subduing nearly all the major Rajput kingdoms and in winning over

their rulers by giving them command of his armies and marrying into their

families: his chief queen and Jahangir's mother was a Rajput princess from Amber.

Spending long periods at the imperial court, the rajas and their sons naturally

began to imitate its customs and fashions. From around i600 sonic of them

employed artists trained in the Mughal studio, who worked in a hybrid style of

Hindu manuscript illustration which is usually called Popular Mughal. Later in

the 17th century some of the rajas were able to employ more accomplished

artists, skilled in the portrait styles of the Jahangir and Shah jahan periods.

These and subsequent waves of Mughal influence had varying but sometimes

profound effects on the local schools of Rajasthan and Central India, each of

which assimilated the new conventions in differing degrees to their existing

traditions, as represented for example by Bhairavi ragini.

The closest continuation of the

pre-Mughal style appears in the boldly simplified designs and colour schemes

used in the schools of Malwa and Bundclkhand. In a typical ragatnala picture,

Bhairava raga is depicted in the form of Krishna conversing with a lady in a pavilion

flanked by stylised flowering trees. The primitive expressive power of this

style is scarcely affected by the Popular Mughal influence that was reaching

the Rajasthani courts. It may be contrasted with a version of the same subject,

in this case more correctly conceived: as Shiva (of whom Bhairava, 'the

Terrible: is an epithet), who sits under a flayed elephant skin in a royal

palace attended by maids. This picture belongs to a series painted at Chunar,

near Bermes, in 1591 by artists trained iii Akbar's studio. Its judicious use

of figural modelling and spatial recession as well as the decorative tile-work

and arabesque borders of the painting are all Akbari features. The series must

have belonged at an early date to the rulers of Bundi, whose imperial service

brought them at one stage to Chunar, for its iconography established a norm for

later Bundi ragamalas. At other courts manuscript illustration was

similarlymodified by a more dilute Popular Mughal influence; (A version of

Kakubha ragini, personified as a lovelorn lady whose charms pacify the wild

blackbuck, is composed in an archaic series of registers and combines

old-fashioned landscape conventions with elegantly attenuated figure drawing

and a row of stylised Mughal flowers at the top.

During the second half of the 17th

century portraiture and genre scenes of the Mughal type were introduced at all

the main courts, with varying degrees of adaptation to the Rajput vision. Jaswant

Singh of Jodphur, who spent much of his life in the imperial service, chose to

patronise work in a strongly Mughal style, as seen in an unfinished drawing of

a durbar scene. However, in later painting at Jodphur, as elsewhere, this

influence became muted and indigenous linear rhythms and colour schemes

reasserted them-selves. Artists at the court of Kotah in particular brought a

unique linear verve to animal subjects such as hunts and elephant fights. The

tumultuous energy of the colliding beasts is evoked by fluid or densely

swirling passages of line and dramatic distortions of anatomical form. This

powerfully empathetic rendering can be contrasted with the flat decorativeness

of the Jain painter's elephant, or with die rich colour effect and strictly

naturalistic modelling of the Deccani and Mughal examples.

Even at the desert-locked court

of Bikaner, where in the late 17th century migrant Muslim artist families had

worked in a Mughal-derived style with some Deccani elements, Rajput conventions

re-appeared within one or two generations. A picture of the autumn month of Karttik,

from a Barahmasa series illustrating the activities of noble lovers during the

twelve months of the year, displays a formalised composition, elongated figures

and vague spatial relationships. A noble and lady stand before a pavilion with

a bed-chamber; another bed is prepared on the roof. In the back-ground a couple

play at chaupar, men bathe and women draw auspicious rangoli patterns on the

ground:

A later and more lyrical fusion

of the ardent sentiments of Hindu devotional poetry with the polished 18th

century Mughal style occurred at Kishangarh, whose ruler, Savant Singh

(1748-57), was himself air accomplished poet. The love sports of Krishna and

Radha were depicted in palace and lakeside settings similar to those of

Kishangarh, and may have been based on Savant Singh's love for a dancer at his

court, with whom he eventually retired to the holy city of Brindabanput the

perilously mannered sweetness of the Kishangarb style soon turned to a cloying

sentimentality.

The Ranas of Mewar, who had

long been regarded as the premier ruling family and the custodians of Rajput

honour, had been the last to capitulate to the Mughals. During the 17th

century they continued their earlier traditions of manuscript illustration in a

bright and forceful style modified by some Popular Mughal influence. But from

the early i8th century the Udaipur artists' best work consisted of ambitious

and original paintings of court life: portraits, durbars, processions, hunts,

religious festivals and zenana scenes, often of unusually large size and full

of anecdotal detail. Some of the better compositions made use of architectural

settings adapted from the palace buildings at Udaipur. Individual portraits of

the Mughal type, showing an isolated figure seated or standing in profile, were

often wooden, but a curious study of an obese courtier in a striped pink pyjama

has a keen satirical edge.

The dissolution of Mughal power

in the 18th century was matched by a similar decline at the courts of

Rajasthan. From the 1730s they were repeatedly overrun by the Marathas from the

south, who brought about a political and economic chaos that lasted until the

establishment of British suzerainty in 1818. Jaipur, which had been founded

close to Amber by the distinguished astronomer Raja Sawai Jai Singh

(1693-1743), is said to have reached depths of turpitude and intrigue

exceptional even in an age of general decadence. But painting continued under

its own inherent momentum. The Jaipur artists were much influenced by the hard

contemporary style of Delhi and Lucknow. Even so, a hackneyed subject of a lady

at her toilet could be transformed into a classically Rajput image by the

accentuated outline drawing of the face and figure and the contrast of

unmodelled flesh and background areas with the detail of jewellery, textile

patterns and a flower gardefik A more ebullient late phase of Rajasthani

painting occurred at Kotah under Rao Ram Singh (1827-65), who is seen passing

in procession through a bazaar, entertained as he rides by a nautch girl

supported on his elephant's tusks If this picture lacks the kinetic force of

the earlier elephant fight, it still has much charm and panache. Already,

however, a harsh synthetic green colour is in use. During the second half of

the-19th century traditional painting either succumbed or was

radically changed by the impact of Western techniques and the sensational art

of photography.

The dissolution of Mughal power

in the 18th century was matched by a similar decline at the courts of

Rajasthan. From the 1730s they were repeatedly overrun by the Marathas from the

south, who brought about a political and economic chaos that lasted until the

establishment of British suzerainty in 1818. Jaipur, which had been founded

close to Amber by the distinguished astronomer Raja Sawai Jai Singh

(1693-1743), is said to have reached depths of turpitude and intrigue

exceptional even in an age of general decadence. But painting continued under

its own inherent momentum. The Jaipur artists were much influenced by the hard

contemporary style of Delhi and Lucknow. Even so, a hackneyed subject of a lady

at her toilet could be transformed into a classically Rajput image by the

accentuated outline drawing of the face and figure and the contrast of

unmodelled flesh and background areas with the detail of jewellery, textile

patterns and a flower gardefik A more ebullient late phase of Rajasthani

painting occurred at Kotah under Rao Ram Singh (1827-65), who is seen passing

in procession through a bazaar, entertained as he rides by a nautch girl

supported on his elephant's tusks If this picture lacks the kinetic force of

the earlier elephant fight, it still has much charm and panache. Already,

however, a harsh synthetic green colour is in use. During the second half of

the-19th century traditional painting either succumbed or was

radically changed by the impact of Western techniques and the sensational art

of photography.

Writer – Andrew Topsfield

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Rajput painting in rajasthan and central india"

Post a Comment