Painting

at the Deccani courts grew from a hybrid cultural back-ground comparable to

that of the Mughal school, but with quite different and regrettably short-lived

results. By the 16th century five Muslim sultanates had emerged in the Deccan,

which, acting together for the only time in their history, disposed of the

Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar in 1565. Afterwards they constantly formed

factions and went to war in an almost frivolous manner. Unlike the Mughals, the

Sultans failed to take the business of state-craft and territorial domination

seriously. They put more passion into the pursuit of courtly pleasures and the

patronage of music, literature and the arts. These projects benefited from a

rich cultural mixture of Hindu court traditions inherited from the Vijayanagar

Empire with those introduced by the many Middle Eastern immigrants Persians,

Arabs, Turks and Africans who had been attracted by the wealth of the Deccani

kingdoms. Some European influence was also present, but it was less conspicuous

than in Mughal art The period of greatest achievement lasted only a few

decades, for the empire-building Mughals found little difficulty in subjugating

the Deccani rulers. Of the three courts known to have patronised painting,

Ahmadnagar fell in 1600, while Bijapur and Golconda were finally taken by

Aurangzeb in 1686-7.

Painting

at the Deccani courts grew from a hybrid cultural back-ground comparable to

that of the Mughal school, but with quite different and regrettably short-lived

results. By the 16th century five Muslim sultanates had emerged in the Deccan,

which, acting together for the only time in their history, disposed of the

Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar in 1565. Afterwards they constantly formed

factions and went to war in an almost frivolous manner. Unlike the Mughals, the

Sultans failed to take the business of state-craft and territorial domination

seriously. They put more passion into the pursuit of courtly pleasures and the

patronage of music, literature and the arts. These projects benefited from a

rich cultural mixture of Hindu court traditions inherited from the Vijayanagar

Empire with those introduced by the many Middle Eastern immigrants Persians,

Arabs, Turks and Africans who had been attracted by the wealth of the Deccani

kingdoms. Some European influence was also present, but it was less conspicuous

than in Mughal art The period of greatest achievement lasted only a few

decades, for the empire-building Mughals found little difficulty in subjugating

the Deccani rulers. Of the three courts known to have patronised painting,

Ahmadnagar fell in 1600, while Bijapur and Golconda were finally taken by

Aurangzeb in 1686-7.  Painting

at the Deccani courts grew from a hybrid cultural back-ground comparable to

that of the Mughal school, but with quite different and regrettably short-lived

results. By the 16th century five Muslim sultanates had emerged in the Deccan,

which, acting together for the only time in their history, disposed of the

Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar in 1565. Afterwards they constantly formed

factions and went to war in an almost frivolous manner. Unlike the Mughals, the

Sultans failed to take the business of state-craft and territorial domination

seriously. They put more passion into the pursuit of courtly pleasures and the

patronage of music, literature and the arts. These projects benefited from a

rich cultural mixture of Hindu court traditions inherited from the Vijayanagar

Empire with those introduced by the many Middle Eastern immigrants Persians,

Arabs, Turks and Africans who had been attracted by the wealth of the Deccani

kingdoms. Some European influence was also present, but it was less conspicuous

than in Mughal art The period of greatest achievement lasted only a few

decades, for the empire-building Mughals found little difficulty in subjugating

the Deccani rulers. Of the three courts known to have patronised painting,

Ahmadnagar fell in 1600, while Bijapur and Golconda were finally taken by

Aurangzeb in 1686-7.

Painting

at the Deccani courts grew from a hybrid cultural back-ground comparable to

that of the Mughal school, but with quite different and regrettably short-lived

results. By the 16th century five Muslim sultanates had emerged in the Deccan,

which, acting together for the only time in their history, disposed of the

Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar in 1565. Afterwards they constantly formed

factions and went to war in an almost frivolous manner. Unlike the Mughals, the

Sultans failed to take the business of state-craft and territorial domination

seriously. They put more passion into the pursuit of courtly pleasures and the

patronage of music, literature and the arts. These projects benefited from a

rich cultural mixture of Hindu court traditions inherited from the Vijayanagar

Empire with those introduced by the many Middle Eastern immigrants Persians,

Arabs, Turks and Africans who had been attracted by the wealth of the Deccani

kingdoms. Some European influence was also present, but it was less conspicuous

than in Mughal art The period of greatest achievement lasted only a few

decades, for the empire-building Mughals found little difficulty in subjugating

the Deccani rulers. Of the three courts known to have patronised painting,

Ahmadnagar fell in 1600, while Bijapur and Golconda were finally taken by

Aurangzeb in 1686-7.

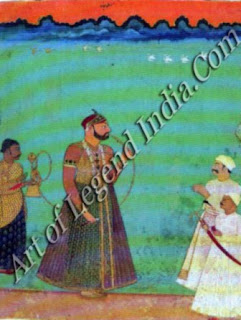

Those

early Deccani paintings which survive are now scattered in many collections.

Though few in numbers, they are remarkably consistent in quality, combining a

high degree of finish with a playful refinement of line and subtle richness of

palette. Portraits of rulers lack the sober, documentary realism or portentous

imperial symbolism of their Mughal counterparts. They are imbued instead with a

mood of indolent enjoyment, a conscious and self-absorbed appreciation of the

passing moment. The most outstanding single patron was Ibrahim Adil Shah of

Bijapur (1579-1627), who is seen in plate 14 seated with a lady in a palace

chaniber in a delicate (though somewhat later) grisaille study embellished with

gold and colouring. Ibrahim was above all things a rasika, a Sanskrit term for

the man of highly developed sensibility, one who is cognisant of the rasas(literally,

'juice' or 'essence'), the sublimated emotional states on which Indian

aesthetics are based: they can be approxi-matcly translated as love, heroism,

disgust, rage, terror, joy, com-passion, wonder and peace. He composed a book

of lyrics, the Kitab-i Nauras (Book of the Nine Rasas), which contains

invocations both to the Hindu deities Sarasvati and Ganesha and a Muslim saint,

as well as to his favourite elephant and the beloved lute, named Moti Khan,

with which he would accompany his singing. He was a master of the slow and

dignified dhrupad vocal style, and generous provision was made for the

thousands of court musicians in his new city of Nauraspur (City of the Nine

Rasas). Besides fine elephants, he had a weakness for jewels and mangoes (a

plate of them appears beside him here) and he enjoyed taming falcons and

parrots. He is said to have written a treatise on chess describing various new

and baffling moves, but he did not excel as a statesman or general.

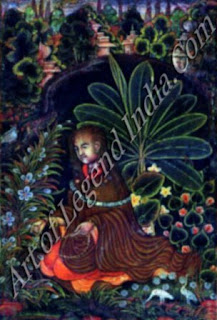

A study

of a richly caparisoned horse held by a groom, whose costume shows some

European influence is the work of one of lbrahim's leading painters. Its

freshness of colouring is set off by the use of gold, and the trees and plants

arc suggested by a deftly attenuated line and delicate stippling. A painting of

a female ascetic seated by a stream [plate x6], although it is another later and

less fine version of an original work of lbrahim's period, displays the lush

landscape conventions and compact density of composition of Bijapur painting.

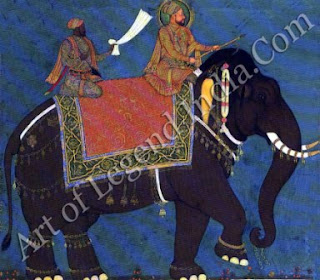

In 1636

Bijapur was compelled to accept Mughal suzerainty. Lavish exchanges of presents

always accompanied political relations between states, and paintings as well as

elephants, jewels and money travelled in both directions. The fully developed

Mughal style of portraiture inevitably began to influence contemporary work at

Bijapur and Golconda. Even so, its naturalistic conventions were often

interpreted with subtlety and splendour by the southern artists. A portrait of

Muhammad Adil Shah (1627-56) riding an elephant, accompanied by his minister

who fans him, is derived from a Mughal model, as seen for example in a

brush-drawing of a Mughal prince riding the elephant Mahabir Deb; as if happens,

the inscription in Shah Jahan's hand records that this elephant was presented

to him as tribute by Muhammad Adil Shah. While the Mughal artist has

meticulously emphasized the finely textured wrinkles and mottling of the

elephant's skin, the two Deccani painters have set its smoky dark mass against

a vivid blue ground, throwing into relief the sumptuous textile patterns and

the Sultan's gold coat, which has been minutely pricked to catch the light.

From

the 165os the Bijapur and Golconda artists lost their earlier inspiration, and

their work declined into more insipid versions of Mughal themes. Aurangzcb's

conquest finally disrupted their traditions. In the 18th century, however, as

Mughal control of the provinces weakened, the viceroy Asaf Jah was able to

establish an independent dynasty based at Hyderabad, near Golconda. Tainting

began to flourish there in a style which mixed the romantic flavor of the

former Golconda school with an increasing Mughal pallor and rigidity.

Nevertheless, a portrait of a Hyderabad minister retains considerable delicacy

of composition and detail. Versions of the Hyderabad style were widely

patronised. A painting from the Maratha court at Tanjore in the far south is

one of the last in a long line of Deccani procession scenes. Raja Tuljaji

(1765-87) appears as always in profile, wearing a flowered gold coat and riding

a frisky horse; but his retainers already show the influence of the Company

style. Within a few years his adopted son Sarabhoji, who had been tutored by

the Danish missionary Swartz, would be patronising natural history painting of

the European type.

Writer-Andrew Topsfield

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Painting of the Deccan in Indian Court Painting"

Post a Comment