The aim

of the Hindu being to break this chain of birth and rebirth that binds him to

the earth, the first step to be taken on this path is for each one to perform

well his own dharma or righteous duties. Hinduism is unique because it

differentiates between the duties of man and man, as also between the duties to

be followed at various stages of one's life. Lord Rama's dharma as an exile for

14 years was different to his later dharma as a ruler. The teacher, the nurse,

the priest, a mother or father each has to follow his or her own dharma.

Duties, whatever they are, have to be performed with excellence and moral

purity as the goal.

The

concept of Dharma is fundamental to Hinduism, as it is believed that it is only

through the pursuit of Dharma that there is social harmony and peace in the

world. The pursuit of Adharma (a path that rejects righteousness) leads to

conflicts, discord and imbalance.

The

saying, Dharanat Dharmah' means Dharma sustains the world and it is that which

holds the world together. It is duty performed with righteousness, with

discipline and moral and spiritual excellence. Varnashrama Dharma is

fundamental to Hindu belief and includes the duties of the various occupations,

orders and classes (Varna) and the duties in the four stages (ashramas) of

one's life. It enjoins that each person's dharma or duty depends on his

occupation, position, moral and spiritual development, age and marital status.

The Caste System

Although

the caste system has now been legally abolished, it is interesting to know its

origin. The original meaning of the word `varna' was order or class of people.

When the Indo-Aryans invaded the country, they came across the local

inhabitants whom they called Dasas or Dasyus. Instead of destroying them after

conquest, as has happened in other civilizations, they absorbed them by giving

them a lower but definite place in their society.

Although

the caste system has now been legally abolished, it is interesting to know its

origin. The original meaning of the word `varna' was order or class of people.

When the Indo-Aryans invaded the country, they came across the local

inhabitants whom they called Dasas or Dasyus. Instead of destroying them after

conquest, as has happened in other civilizations, they absorbed them by giving

them a lower but definite place in their society.

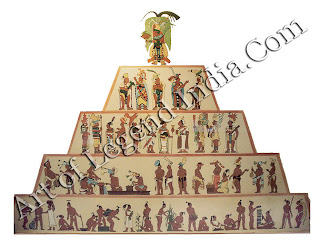

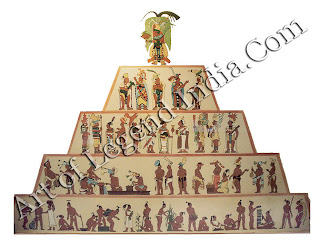

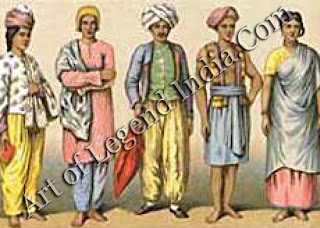

In time

this system came to be four-tiered, with four classes, the Brahmanas or

Brahmins (not to be confused with the Brahman) who were the teachers and

priests, the Kshatriyas or warriors and rulers, the Vaishyas, those who

followed commercial occupations, and the Sudras who performed manual labour and

were also farmers and agriculturists. The word 'varna' therefore implied the

social order and not caste, as even Manu has given the difference between Varna

(class or order) and jati (sect of birth or caste). A man's Varna depended as

much on his mental and physical equipment as on heritage. Therefore it was a

fluid state. A Brahmin for example, was one who evolved with the guna or

qualities and performed the karma, or action, enjoined on a Brahmin. (It was

only later that the word `varna' came to mean colour.)

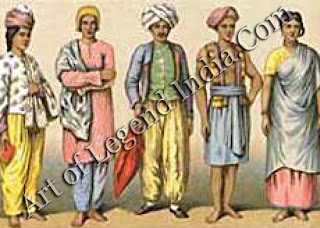

The

jails (or sects) in time became more important than the four main classes. These

were mainly occupational (like the goldsmith jail, the weaver jati, the

carpenter jail etc.) and served the purpose of guilds which protected the

interests of their members, trained the young and saw to it that no outsider

entered the fold. In time these jails or sects grouped themselves under the

main classes which is why we speak today of four castes. However, it is not the

caste of a man but his sect that is important to this day. Even today these

sects often do not permit fluidity of movement, even where the old occupations

have broken down and new ones have come in.

The

untouchables or outcastes were originally those who had broken certain caste

rules. For example, the Nayadis, who were considered outcastes of the lowest

order, were originally Brahmins who were excommunicated for some reason. Also

later the Hindus, who were originally meat-eaters, slowly changed their eating

habits to vegetarianism, especially the Brahmins and Vaishyas who were

influenced by early Buddhism and Jainism. With this change, those who ate beef

or the meat of certain proscribed animals came to be considered outcastes or

untouchables, as, by this time, the cow had come to be regarded akin to a

mother, the people, being largely rural, having to depend on the cow's products

for sustenance. (This is why the cow is given the reverence due to a mother in

Hindu society to this day.)

However

there is no religious sanction whatsoever in Hinduism to the concept of

untouchability although later additions on the subject were inserted into the

earlier scriptures to justify its existence. It was a purely social practice

introduced by the upper castes to provide themselves with menial labour to

perform certain tasks repulsive to themselves such as those of cemetery

keepers, scavengers and cleaners. Hindu society has much to answer for this

inhuman treatment of a whole section of its own people, but the Hindu religion

had nothing to do with it.

However

there is no religious sanction whatsoever in Hinduism to the concept of

untouchability although later additions on the subject were inserted into the

earlier scriptures to justify its existence. It was a purely social practice

introduced by the upper castes to provide themselves with menial labour to

perform certain tasks repulsive to themselves such as those of cemetery

keepers, scavengers and cleaners. Hindu society has much to answer for this

inhuman treatment of a whole section of its own people, but the Hindu religion

had nothing to do with it.

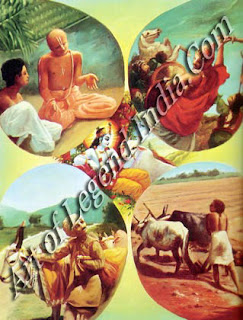

These

four classes were not as rigid in ancient times as they became later. In the

Upanishads is the story of Satyakama, neither son of a servant maid, Jabala,

who did not know his gotra or clan of origin as even his mother did not know

who his father was nor his caste. He went to a great teacher known for his

wisdom that took young Brahmin boys as disciples, and told him the truth of his

parentage. He gave his name as Satyakama Jabala, after his mother. The Guru,

impressed with the truthfulness of the young man, initiated him as a

Brahmachari or student under him. He then gave him 400 head of cattle and asked

him to take them to the forest and to return only when these became a thousand

in number.

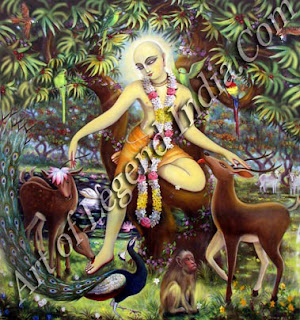

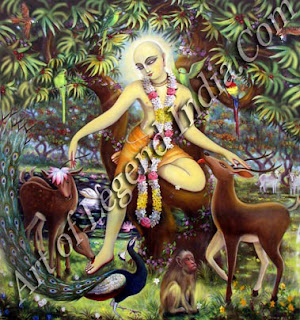

While

living in the forest alone for years, Satyakama learnt of the Brahman, the

Absolute, from communing with Nature, from the clouds in the skies, from the

music of the birds, from the trees and the flowers and from the beauty of all

Creation around and about him.

While

living in the forest alone for years, Satyakama learnt of the Brahman, the

Absolute, from communing with Nature, from the clouds in the skies, from the

music of the birds, from the trees and the flowers and from the beauty of all

Creation around and about him.

After

he had 1000 head of cattle he returned. When his Guru gazed at the brilliant, shining

face of his pupil, he knew that the young man had realised the Brahman and had

only to complete this knowledge by study with his teacher. Although only

Brahmins were initiated into higher religious education not birth alone but

aptitude also permitted the upward movement of the castes in Upanishadic times,

as seen by the beautiful story of Satyakama Jabala.

The

great Brahmin Rishi, Vyasa, was born when Parashara, the grandson of the Rishi

Vasishta, fell in love with a beautiful dark-skinned woman of the fisher tribe,

later named Satyavati. The child born to them was named Krishna Dvaipayana,

after his dark colour (krishna) taken after his mother, and the island (dvipa)

on which he was born. Only later did he become known as Veda Vyasa. Yet his

knowledge of the Vedas determined his caste as a Brahmin Rishi and not his

birth to a fisherwoman of a low caste.

Vyasa is often worshipped as divinity in

human form, so great is the regard given to him by Hindus through the ages. His

birth to a tribal fisherwoman was not looked down upon, nor did it affect his

position as a Brahmin sage of the highest caste.

Vyasa is often worshipped as divinity in

human form, so great is the regard given to him by Hindus through the ages. His

birth to a tribal fisherwoman was not looked down upon, nor did it affect his

position as a Brahmin sage of the highest caste.

(Similarly

Valmiki, the author of the epic, the Ramayana, was a hunter of the lowest caste

who came to be considered a Brahmin Rishi by virtue of his erudition.)

Satyavati subsequently married Santanu, King of Hastinapura. Her son

Vichitravirya could not bear any children and her step-son, Bhishma, would not

do so in view of a promise given to his late father not to marry or bear

children, so that Satyavati's progeny would rule the kingdom.

According

to the Niyoga custom of the times, on the death of a childless man or even if

he were alive but could not father children, his brother could father children

on his behalf. When it was found that her sons could not bear children, the

great queen, Satyavati, called on the son born to her through Sage Parashara,

the Sage Vyasa, and asked him to father children by her two daughters-in-law,

which he did. A servant woman of the palace approached Vyasa in a spirit of

great devotion and to her was born Vidura considered again one of the greatest

of Brahmin sages (in view of his wisdom and knowledge of the Dharma Shastras)

in spite of his mother being a servant woman of the lowest caste.

According

to the Niyoga custom of the times, on the death of a childless man or even if

he were alive but could not father children, his brother could father children

on his behalf. When it was found that her sons could not bear children, the

great queen, Satyavati, called on the son born to her through Sage Parashara,

the Sage Vyasa, and asked him to father children by her two daughters-in-law,

which he did. A servant woman of the palace approached Vyasa in a spirit of

great devotion and to her was born Vidura considered again one of the greatest

of Brahmin sages (in view of his wisdom and knowledge of the Dharma Shastras)

in spite of his mother being a servant woman of the lowest caste.

It was

from the sons of Vyasa that the Pandavas and the Kauravas were descended. Their

great-grandmother, Satyavati, belonged to a fisher tribe and their great-grandfather,

Parashara, was a Brahmin sage. Yet because they were princes of the royal house

of Hastinapura, they were considered Kshatriyas. In actual fact they were not

so by birth, only by occupation, once again proving that caste was purely

occupational.

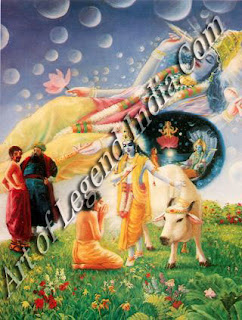

Utanga,

a childhood Brahmin friend of Krishna, took a boon from him that, in his

wanderings, Krishna would provide him with water whenever he needed it. Once,

when he felt very thirsty, he thought of the Lord and suddenly a Nishada (an

outcaste hunter) appeared before him clothed in filthy rags, and offered water

from his animal-skin water-bag. Utanga refused it and berated Krishna in his

mind, as he felt he had not kept to his promise.

The Nishada tried to persuade

Utanga again and again to drink the water but Utanga was adamant. The hunter

then disappeared and the Lord appeared before Utanga and told him that he had

sent Indra, King of the Devas, as a hunter with amrita, the nectar of

immortality. Since Utanga had not shown any wisdom but had continued to

differentiate between man and man based on externals such as caste, he had

missed the rare chance of attaining immortality. The moral of this story is

obvious.

The Nishada tried to persuade

Utanga again and again to drink the water but Utanga was adamant. The hunter

then disappeared and the Lord appeared before Utanga and told him that he had

sent Indra, King of the Devas, as a hunter with amrita, the nectar of

immortality. Since Utanga had not shown any wisdom but had continued to

differentiate between man and man based on externals such as caste, he had

missed the rare chance of attaining immortality. The moral of this story is

obvious.

The

disciples of the great philosopher, Adi Shankara, once asked a Chandala (an

outcaste), to move away from his path. "Who are you and who am I? Is the

Self within me different from yours?" queried the Chandala (believed to be

Shiva in disguise). Shankara, realising the wisdom of these words, prostrated

before the Chandala saying, "One who is established in the Brahman, be he

a low-born Chandala or a twice-born Brahmin, verily I declare him my

Guru".

As late

as in the 8th century, an untouchable could be considered a Guru by

one born a brahmin like Adi Shankara.

Writer – Shakunthala Jagannathan

Although

the caste system has now been legally abolished, it is interesting to know its

origin. The original meaning of the word `varna' was order or class of people.

When the Indo-Aryans invaded the country, they came across the local

inhabitants whom they called Dasas or Dasyus. Instead of destroying them after

conquest, as has happened in other civilizations, they absorbed them by giving

them a lower but definite place in their society.

Although

the caste system has now been legally abolished, it is interesting to know its

origin. The original meaning of the word `varna' was order or class of people.

When the Indo-Aryans invaded the country, they came across the local

inhabitants whom they called Dasas or Dasyus. Instead of destroying them after

conquest, as has happened in other civilizations, they absorbed them by giving

them a lower but definite place in their society.  However

there is no religious sanction whatsoever in Hinduism to the concept of

untouchability although later additions on the subject were inserted into the

earlier scriptures to justify its existence. It was a purely social practice

introduced by the upper castes to provide themselves with menial labour to

perform certain tasks repulsive to themselves such as those of cemetery

keepers, scavengers and cleaners. Hindu society has much to answer for this

inhuman treatment of a whole section of its own people, but the Hindu religion

had nothing to do with it.

However

there is no religious sanction whatsoever in Hinduism to the concept of

untouchability although later additions on the subject were inserted into the

earlier scriptures to justify its existence. It was a purely social practice

introduced by the upper castes to provide themselves with menial labour to

perform certain tasks repulsive to themselves such as those of cemetery

keepers, scavengers and cleaners. Hindu society has much to answer for this

inhuman treatment of a whole section of its own people, but the Hindu religion

had nothing to do with it.  While

living in the forest alone for years, Satyakama learnt of the Brahman, the

Absolute, from communing with Nature, from the clouds in the skies, from the

music of the birds, from the trees and the flowers and from the beauty of all

Creation around and about him.

While

living in the forest alone for years, Satyakama learnt of the Brahman, the

Absolute, from communing with Nature, from the clouds in the skies, from the

music of the birds, from the trees and the flowers and from the beauty of all

Creation around and about him.  Vyasa is often worshipped as divinity in

human form, so great is the regard given to him by Hindus through the ages. His

birth to a tribal fisherwoman was not looked down upon, nor did it affect his

position as a Brahmin sage of the highest caste.

Vyasa is often worshipped as divinity in

human form, so great is the regard given to him by Hindus through the ages. His

birth to a tribal fisherwoman was not looked down upon, nor did it affect his

position as a Brahmin sage of the highest caste.  According

to the Niyoga custom of the times, on the death of a childless man or even if

he were alive but could not father children, his brother could father children

on his behalf. When it was found that her sons could not bear children, the

great queen, Satyavati, called on the son born to her through Sage Parashara,

the Sage Vyasa, and asked him to father children by her two daughters-in-law,

which he did. A servant woman of the palace approached Vyasa in a spirit of

great devotion and to her was born Vidura considered again one of the greatest

of Brahmin sages (in view of his wisdom and knowledge of the Dharma Shastras)

in spite of his mother being a servant woman of the lowest caste.

According

to the Niyoga custom of the times, on the death of a childless man or even if

he were alive but could not father children, his brother could father children

on his behalf. When it was found that her sons could not bear children, the

great queen, Satyavati, called on the son born to her through Sage Parashara,

the Sage Vyasa, and asked him to father children by her two daughters-in-law,

which he did. A servant woman of the palace approached Vyasa in a spirit of

great devotion and to her was born Vidura considered again one of the greatest

of Brahmin sages (in view of his wisdom and knowledge of the Dharma Shastras)

in spite of his mother being a servant woman of the lowest caste.  The Nishada tried to persuade

Utanga again and again to drink the water but Utanga was adamant. The hunter

then disappeared and the Lord appeared before Utanga and told him that he had

sent Indra, King of the Devas, as a hunter with amrita, the nectar of

immortality. Since Utanga had not shown any wisdom but had continued to

differentiate between man and man based on externals such as caste, he had

missed the rare chance of attaining immortality. The moral of this story is

obvious.

The Nishada tried to persuade

Utanga again and again to drink the water but Utanga was adamant. The hunter

then disappeared and the Lord appeared before Utanga and told him that he had

sent Indra, King of the Devas, as a hunter with amrita, the nectar of

immortality. Since Utanga had not shown any wisdom but had continued to

differentiate between man and man based on externals such as caste, he had

missed the rare chance of attaining immortality. The moral of this story is

obvious.

0 Response to "Introduction to Dharma "

Post a Comment