The

ceiling of the cave contains a picture of a magnificent lake with beautiful

buffaloes, geese and fish frolicking amidst lotuses in bud and bloom, in the

gathering of which some youths are shown engaged. The figures are drawn with

great care and delicacy of feeling. The most magnificent of the paintings,

however, are the king wearing a lovely crown and accompanied by his queen, with

an umbrella raised over both, and two female dancers of exquisite grace and

proportions, all presented on the cubical parts of the pillars of the mandapa.

Much of this has been ruined by weather and vandalism. There is still enough

left to help us judge the skill of the painter during the early phase of

Pandyan rule. The coiffure of the dancers, the lines composing the face, the

contour of the body in beautiful flexions, the attitude of the hands in

rhythmic dance motion is the work of a great master. The grace of the crown

with minute details of workmanship and the dignity of the royal figure in the

company of his consort cannot be praised too highly.

The

ceiling of the cave contains a picture of a magnificent lake with beautiful

buffaloes, geese and fish frolicking amidst lotuses in bud and bloom, in the

gathering of which some youths are shown engaged. The figures are drawn with

great care and delicacy of feeling. The most magnificent of the paintings,

however, are the king wearing a lovely crown and accompanied by his queen, with

an umbrella raised over both, and two female dancers of exquisite grace and

proportions, all presented on the cubical parts of the pillars of the mandapa.

Much of this has been ruined by weather and vandalism. There is still enough

left to help us judge the skill of the painter during the early phase of

Pandyan rule. The coiffure of the dancers, the lines composing the face, the

contour of the body in beautiful flexions, the attitude of the hands in

rhythmic dance motion is the work of a great master. The grace of the crown

with minute details of workmanship and the dignity of the royal figure in the

company of his consort cannot be praised too highly.

Like

the Pallava king Mahendravarman, who was converted by Appar, the older

contemporary of Tirujnanasam-bandar, Arikesari Parankusa, the Pandyan king, was

re-claimed from Jainism by the saint, Tirujnanasam-bandar, in the latter half

of the seventh century A. D. This king with the zeal of a new convert and with

the enthusiastic support of his queen advanced his faith.

During

the time of Simhavishnu, who overcame the Pandyas, his son Mahendravarman and

grandson Narasimhavarman, who dominated in the South during his time, as the

vanquisher of even Pulakesin of the Western Chalukya dynasty, Pallava influence

was dominant in the South. The Pandya king Maravarman Rajasimha, also known as

Pallavabhanjana, found it a favourable moment to attack the Pallavas during the

time of Nandivarman Pallavamalla. His son Nedunjadayan had a minister

uttarantantri Marangari alias Madhurakavi, who excavated a temple for Vishnu in

the Annamalai hill in the neighbor-hood of Madurai and recorded it in an

inscription. It is this history of the early Pandyas which should help us

under-stand why both the cave temples and the rock-cut free standing temples of

the Pandyas so closely resemble and recall those of the early Pallavas.

The

Pandyas, like the Chalukyas, were frequently fighting the Pallavas, but

nevertheless were struck with the beauty of the Pallava cave temples and

monolithic shrines.

They

had also a matrimonial alliance with the Pallavas as in the case of Kochchadayan,

the father of Maravarman Rajasimha, and the aesthetic taste of a princess of

the Pallava line would not have gone without self-expression, specially when we

remember that Rangapataka, the queen of Pallava Rajasimha, associated herself

with her husband in the construction of lovely temples at Kanchipuram, and this

artistic taste was inborn in their family. It is no wonder therefore that,

considering the proximity of the Pallava country, with the Chera power

practically eclipsed at the time, the Pandyas adopted the ideas of the Pallavas

in architecture, sculpture and painting.

In the

Tirumalaipuram cave temple, there are fragments discovered by Professor Jouveau

Dubreuil to show specimens of the painter's art in the early Pandyan period.

The cave closely resembles the Pallava caves of Mahendravarman. Though most of

the paintings here are obliterated, the few that remain show the dexterity of

the painter in portraying such themes as the swan or the duck and lotuses in

bud and bloom in pleasing patterns covering the ceiling and on the pillar

brackets.

There

are also themes like hunters and their wives, one of whom is shown carrying a

wild boar after a hunt. This theme of bacchanalian orgies suggests traces of

foreign influence, which is explained by the fact that the Pandyan kingdom was

a rich commercial centre, with contacts all over the civilised world, specially

with Rome, from the early centuries of the Christian era. The pearls of the

Pandyan fisheries were greatly in demand in Rome and a regular colony of

Yavanas existed at Madurai.

To

Professor Jouveau Dubreuil, we owe the discovery of paintings similar to those

at Ajanta in Sittannavasal. These are in the best tradition of classical art

and were originally believed to be Pallava. It is now found that there are two

layers of paintings, an earlier one and a later one, as also an inscription which

proves that what were originally reckoned Pallava are really Pandyan paintings

of the ninth century A.D.

The

ceiling of the cave contains a picture of a magnificent lake with beautiful

buffaloes, geese and fish frolicking amidst lotuses in bud and bloom, in the

gathering of which some youths are shown engaged. The figures are drawn with

great care and delicacy of feeling. The most magnificent of the paintings,

however, are the king wearing a lovely crown and accompanied by his queen, with

an umbrella raised over both, and two female dancers of exquisite grace and

proportions, all presented on the cubical parts of the pillars of the mandapa.

Much of this has been ruined by weather and vandalism. There is still enough

left to help us judge the skill of the painter during the early phase of

Pandyan rule. The coiffure of the dancers, the lines composing the face, the

contour of the body in beautiful flexions, the attitude of the hands in

rhythmic dance motion is the work of a great master. The grace of the crown

with minute details of workmanship and the dignity of the royal figure in the

company of his consort cannot be praised too highly.

The

ceiling of the cave contains a picture of a magnificent lake with beautiful

buffaloes, geese and fish frolicking amidst lotuses in bud and bloom, in the

gathering of which some youths are shown engaged. The figures are drawn with

great care and delicacy of feeling. The most magnificent of the paintings,

however, are the king wearing a lovely crown and accompanied by his queen, with

an umbrella raised over both, and two female dancers of exquisite grace and

proportions, all presented on the cubical parts of the pillars of the mandapa.

Much of this has been ruined by weather and vandalism. There is still enough

left to help us judge the skill of the painter during the early phase of

Pandyan rule. The coiffure of the dancers, the lines composing the face, the

contour of the body in beautiful flexions, the attitude of the hands in

rhythmic dance motion is the work of a great master. The grace of the crown

with minute details of workmanship and the dignity of the royal figure in the

company of his consort cannot be praised too highly.

Writer – C. Shivaramamurti

The aim

of the Hindu being to break this chain of birth and rebirth that binds him to

the earth, the first step to be taken on this path is for each one to perform

well his own dharma or righteous duties. Hinduism is unique because it

differentiates between the duties of man and man, as also between the duties to

be followed at various stages of one's life. Lord Rama's dharma as an exile for

14 years was different to his later dharma as a ruler. The teacher, the nurse,

the priest, a mother or father each has to follow his or her own dharma.

Duties, whatever they are, have to be performed with excellence and moral

purity as the goal.

The

concept of Dharma is fundamental to Hinduism, as it is believed that it is only

through the pursuit of Dharma that there is social harmony and peace in the

world. The pursuit of Adharma (a path that rejects righteousness) leads to

conflicts, discord and imbalance.

The

saying, Dharanat Dharmah' means Dharma sustains the world and it is that which

holds the world together. It is duty performed with righteousness, with

discipline and moral and spiritual excellence. Varnashrama Dharma is

fundamental to Hindu belief and includes the duties of the various occupations,

orders and classes (Varna) and the duties in the four stages (ashramas) of

one's life. It enjoins that each person's dharma or duty depends on his

occupation, position, moral and spiritual development, age and marital status.

The Caste System

Although

the caste system has now been legally abolished, it is interesting to know its

origin. The original meaning of the word `varna' was order or class of people.

When the Indo-Aryans invaded the country, they came across the local

inhabitants whom they called Dasas or Dasyus. Instead of destroying them after

conquest, as has happened in other civilizations, they absorbed them by giving

them a lower but definite place in their society.

Although

the caste system has now been legally abolished, it is interesting to know its

origin. The original meaning of the word `varna' was order or class of people.

When the Indo-Aryans invaded the country, they came across the local

inhabitants whom they called Dasas or Dasyus. Instead of destroying them after

conquest, as has happened in other civilizations, they absorbed them by giving

them a lower but definite place in their society.

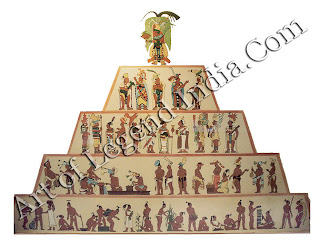

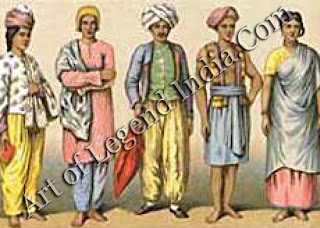

In time

this system came to be four-tiered, with four classes, the Brahmanas or

Brahmins (not to be confused with the Brahman) who were the teachers and

priests, the Kshatriyas or warriors and rulers, the Vaishyas, those who

followed commercial occupations, and the Sudras who performed manual labour and

were also farmers and agriculturists. The word 'varna' therefore implied the

social order and not caste, as even Manu has given the difference between Varna

(class or order) and jati (sect of birth or caste). A man's Varna depended as

much on his mental and physical equipment as on heritage. Therefore it was a

fluid state. A Brahmin for example, was one who evolved with the guna or

qualities and performed the karma, or action, enjoined on a Brahmin. (It was

only later that the word `varna' came to mean colour.)

The

jails (or sects) in time became more important than the four main classes. These

were mainly occupational (like the goldsmith jail, the weaver jati, the

carpenter jail etc.) and served the purpose of guilds which protected the

interests of their members, trained the young and saw to it that no outsider

entered the fold. In time these jails or sects grouped themselves under the

main classes which is why we speak today of four castes. However, it is not the

caste of a man but his sect that is important to this day. Even today these

sects often do not permit fluidity of movement, even where the old occupations

have broken down and new ones have come in.

The

untouchables or outcastes were originally those who had broken certain caste

rules. For example, the Nayadis, who were considered outcastes of the lowest

order, were originally Brahmins who were excommunicated for some reason. Also

later the Hindus, who were originally meat-eaters, slowly changed their eating

habits to vegetarianism, especially the Brahmins and Vaishyas who were

influenced by early Buddhism and Jainism. With this change, those who ate beef

or the meat of certain proscribed animals came to be considered outcastes or

untouchables, as, by this time, the cow had come to be regarded akin to a

mother, the people, being largely rural, having to depend on the cow's products

for sustenance. (This is why the cow is given the reverence due to a mother in

Hindu society to this day.)

However

there is no religious sanction whatsoever in Hinduism to the concept of

untouchability although later additions on the subject were inserted into the

earlier scriptures to justify its existence. It was a purely social practice

introduced by the upper castes to provide themselves with menial labour to

perform certain tasks repulsive to themselves such as those of cemetery

keepers, scavengers and cleaners. Hindu society has much to answer for this

inhuman treatment of a whole section of its own people, but the Hindu religion

had nothing to do with it.

However

there is no religious sanction whatsoever in Hinduism to the concept of

untouchability although later additions on the subject were inserted into the

earlier scriptures to justify its existence. It was a purely social practice

introduced by the upper castes to provide themselves with menial labour to

perform certain tasks repulsive to themselves such as those of cemetery

keepers, scavengers and cleaners. Hindu society has much to answer for this

inhuman treatment of a whole section of its own people, but the Hindu religion

had nothing to do with it.

These

four classes were not as rigid in ancient times as they became later. In the

Upanishads is the story of Satyakama, neither son of a servant maid, Jabala,

who did not know his gotra or clan of origin as even his mother did not know

who his father was nor his caste. He went to a great teacher known for his

wisdom that took young Brahmin boys as disciples, and told him the truth of his

parentage. He gave his name as Satyakama Jabala, after his mother. The Guru,

impressed with the truthfulness of the young man, initiated him as a

Brahmachari or student under him. He then gave him 400 head of cattle and asked

him to take them to the forest and to return only when these became a thousand

in number.

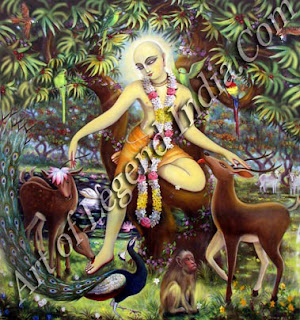

While

living in the forest alone for years, Satyakama learnt of the Brahman, the

Absolute, from communing with Nature, from the clouds in the skies, from the

music of the birds, from the trees and the flowers and from the beauty of all

Creation around and about him.

While

living in the forest alone for years, Satyakama learnt of the Brahman, the

Absolute, from communing with Nature, from the clouds in the skies, from the

music of the birds, from the trees and the flowers and from the beauty of all

Creation around and about him.

After

he had 1000 head of cattle he returned. When his Guru gazed at the brilliant, shining

face of his pupil, he knew that the young man had realised the Brahman and had

only to complete this knowledge by study with his teacher. Although only

Brahmins were initiated into higher religious education not birth alone but

aptitude also permitted the upward movement of the castes in Upanishadic times,

as seen by the beautiful story of Satyakama Jabala.

The

great Brahmin Rishi, Vyasa, was born when Parashara, the grandson of the Rishi

Vasishta, fell in love with a beautiful dark-skinned woman of the fisher tribe,

later named Satyavati. The child born to them was named Krishna Dvaipayana,

after his dark colour (krishna) taken after his mother, and the island (dvipa)

on which he was born. Only later did he become known as Veda Vyasa. Yet his

knowledge of the Vedas determined his caste as a Brahmin Rishi and not his

birth to a fisherwoman of a low caste.

Vyasa is often worshipped as divinity in

human form, so great is the regard given to him by Hindus through the ages. His

birth to a tribal fisherwoman was not looked down upon, nor did it affect his

position as a Brahmin sage of the highest caste.

Vyasa is often worshipped as divinity in

human form, so great is the regard given to him by Hindus through the ages. His

birth to a tribal fisherwoman was not looked down upon, nor did it affect his

position as a Brahmin sage of the highest caste.

Vyasa is often worshipped as divinity in

human form, so great is the regard given to him by Hindus through the ages. His

birth to a tribal fisherwoman was not looked down upon, nor did it affect his

position as a Brahmin sage of the highest caste.

Vyasa is often worshipped as divinity in

human form, so great is the regard given to him by Hindus through the ages. His

birth to a tribal fisherwoman was not looked down upon, nor did it affect his

position as a Brahmin sage of the highest caste.

(Similarly

Valmiki, the author of the epic, the Ramayana, was a hunter of the lowest caste

who came to be considered a Brahmin Rishi by virtue of his erudition.)

Satyavati subsequently married Santanu, King of Hastinapura. Her son

Vichitravirya could not bear any children and her step-son, Bhishma, would not

do so in view of a promise given to his late father not to marry or bear

children, so that Satyavati's progeny would rule the kingdom.

According

to the Niyoga custom of the times, on the death of a childless man or even if

he were alive but could not father children, his brother could father children

on his behalf. When it was found that her sons could not bear children, the

great queen, Satyavati, called on the son born to her through Sage Parashara,

the Sage Vyasa, and asked him to father children by her two daughters-in-law,

which he did. A servant woman of the palace approached Vyasa in a spirit of

great devotion and to her was born Vidura considered again one of the greatest

of Brahmin sages (in view of his wisdom and knowledge of the Dharma Shastras)

in spite of his mother being a servant woman of the lowest caste.

According

to the Niyoga custom of the times, on the death of a childless man or even if

he were alive but could not father children, his brother could father children

on his behalf. When it was found that her sons could not bear children, the

great queen, Satyavati, called on the son born to her through Sage Parashara,

the Sage Vyasa, and asked him to father children by her two daughters-in-law,

which he did. A servant woman of the palace approached Vyasa in a spirit of

great devotion and to her was born Vidura considered again one of the greatest

of Brahmin sages (in view of his wisdom and knowledge of the Dharma Shastras)

in spite of his mother being a servant woman of the lowest caste.

It was

from the sons of Vyasa that the Pandavas and the Kauravas were descended. Their

great-grandmother, Satyavati, belonged to a fisher tribe and their great-grandfather,

Parashara, was a Brahmin sage. Yet because they were princes of the royal house

of Hastinapura, they were considered Kshatriyas. In actual fact they were not

so by birth, only by occupation, once again proving that caste was purely

occupational.

Utanga,

a childhood Brahmin friend of Krishna, took a boon from him that, in his

wanderings, Krishna would provide him with water whenever he needed it. Once,

when he felt very thirsty, he thought of the Lord and suddenly a Nishada (an

outcaste hunter) appeared before him clothed in filthy rags, and offered water

from his animal-skin water-bag. Utanga refused it and berated Krishna in his

mind, as he felt he had not kept to his promise.

The Nishada tried to persuade

Utanga again and again to drink the water but Utanga was adamant. The hunter

then disappeared and the Lord appeared before Utanga and told him that he had

sent Indra, King of the Devas, as a hunter with amrita, the nectar of

immortality. Since Utanga had not shown any wisdom but had continued to

differentiate between man and man based on externals such as caste, he had

missed the rare chance of attaining immortality. The moral of this story is

obvious.

The Nishada tried to persuade

Utanga again and again to drink the water but Utanga was adamant. The hunter

then disappeared and the Lord appeared before Utanga and told him that he had

sent Indra, King of the Devas, as a hunter with amrita, the nectar of

immortality. Since Utanga had not shown any wisdom but had continued to

differentiate between man and man based on externals such as caste, he had

missed the rare chance of attaining immortality. The moral of this story is

obvious.

The Nishada tried to persuade

Utanga again and again to drink the water but Utanga was adamant. The hunter

then disappeared and the Lord appeared before Utanga and told him that he had

sent Indra, King of the Devas, as a hunter with amrita, the nectar of

immortality. Since Utanga had not shown any wisdom but had continued to

differentiate between man and man based on externals such as caste, he had

missed the rare chance of attaining immortality. The moral of this story is

obvious.

The Nishada tried to persuade

Utanga again and again to drink the water but Utanga was adamant. The hunter

then disappeared and the Lord appeared before Utanga and told him that he had

sent Indra, King of the Devas, as a hunter with amrita, the nectar of

immortality. Since Utanga had not shown any wisdom but had continued to

differentiate between man and man based on externals such as caste, he had

missed the rare chance of attaining immortality. The moral of this story is

obvious.

The

disciples of the great philosopher, Adi Shankara, once asked a Chandala (an

outcaste), to move away from his path. "Who are you and who am I? Is the

Self within me different from yours?" queried the Chandala (believed to be

Shiva in disguise). Shankara, realising the wisdom of these words, prostrated

before the Chandala saying, "One who is established in the Brahman, be he

a low-born Chandala or a twice-born Brahmin, verily I declare him my

Guru".

As late

as in the 8th century, an untouchable could be considered a Guru by

one born a brahmin like Adi Shankara.

Writer – Shakunthala Jagannathan

A MARKET SCENE AT KAND-E-BADAM, WEIGHING AND TRANSPORT OF ALMONDS

Artist, Sur Das

Babur

describes Farghana, its principal towns, villages and rivers in Section I of

the Babur Nama. Andijan was its capital, and Khujand one of its ancient

towns. He thus describes Kand-e-Badam which was known for its almonds:

Babur

describes Farghana, its principal towns, villages and rivers in Section I of

the Babur Nama. Andijan was its capital, and Khujand one of its ancient

towns. He thus describes Kand-e-Badam which was known for its almonds:

"Kand:e-Badam

(village of almonds) is a dependency of Khujand ; though it is not a township

(qasbii) it is rather a good approach to one (ciasbcacha). Its almonds are

excellent, hence its name; they all go to Hormuz or to Hindustan. It is five or

six yighach east of Khu-jand."

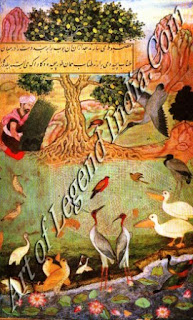

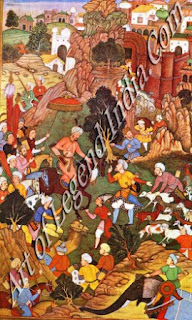

This

painting is by Sur Das. In the background is Kand-e-Badam. In between the domes

of mosques are date-palms, reminding us of an Indian town. On the left a man is

plucking almonds and in the centre almonds are being weighed and bagged. In the

foreground they are being loaded on camels and transported to their

destination. There is action and movement in this painting which vividly

depicts trade in almonds, and how they were brought to India from Central Asia.

BABUR MEETING KHANZADA BEGAM, MEHR BANU. BEGAM AND OTHER LADIES

Artist, Mansur

Khanzada

Begam was the sister of Ba.bur. When he was forced to evacuate Samarkand in

1500 A.D. he was compelled to marry her to Shaibani Khan, his enemy. Shaibani

Khan was defeated by Shah Ismail of Persia, who killed him and made a drinking

cup of his skull. Babur thus describes his reunion with his sister:

"Khanzada

Begam was in Mery when Shah Ismail (Safavi) defeated the Auzbegs near that town

(916 A.H. =1510 A.D.); for my sake he treated her well, giving her sufficient

escort to Qunduz where she rejoined me. We had been apart for some ten years;

when Muhammadi Kukultash and I went to see her, neither she nor those about her

knew us, although I spoke. They recognized us after a time."

This

painting is by Mansur, who distinguished himself in painting birds and animals.

Here he depicts the reunion of brother and sister at Qunduz in Afghanistan.

Seated close to Babur is his companion Kukultash. Seated in front of Babur is

Khanzada Begam attended by maid-servants. Outside the kanat are soldiers armed

with spears, bows and arrows guarding the tent. There is no display of emotions

as the sister did not recognize her brother.

BABUR IN CHAR-BAGH AT ANDI JAN

Babur's

father Urnar Shaikh Mirza died at the fort of Akhsi while tending his pigeons.

As Babur describes, "the fort of Akhsi is situated above a deep ravine,

along this ravine stand the palace buildings, and from it on Monday, Ramzan 4,

Umar Shaikh Mirzd flew, with his pigeons and their house, and became a

falcon."

Babur's

father Urnar Shaikh Mirza died at the fort of Akhsi while tending his pigeons.

As Babur describes, "the fort of Akhsi is situated above a deep ravine,

along this ravine stand the palace buildings, and from it on Monday, Ramzan 4,

Umar Shaikh Mirzd flew, with his pigeons and their house, and became a

falcon."

"At

the time of Umar Shaikh Mirza's accident, I was in the Four Gardens

(Char-biigh) of Andijan. The news reached Andijan on Tuesday, Ramzan 5 (June

9th); I mounted at once, with my followers and retainers, intending to go into

the fort but, on our getting near the Mirza's Gate, Shirim Taghai took hold of

my bridle and moved off towards the Praying Place. It had crossed his mind that

if a great ruler like Si. Ahmad Mirza came in force, the Andijan Begs would

make me over to him and the country, but that if he took me to Auzkint and the

foothills thereabouts, I, at any rate, should not be made over and could go to

one of my mother's (half-) brothers, Sl. Mahmud Khan or Sl. Ahmad Khdn."

The

painting shows Babur mounted on a horse followed by his retainers going to

Akhsi. In the background is the fort of Andijan. The artist has depicted Babur

in a sorrowful mood. In the foreground are soldiers armed with muskets, and a

courtier on horse-back praying with his hands raised.

ACCLAMATION OF NINE STANDARDS

Artist, Jagnath

The

Mughals observed ceremonies and rules which were laid long ago by Chingiz Khan.

For each clan a place was fixed in battle-array. One of their ceremonies was acclamation

of nine standards which is thus described by Babur:

The

Mughals observed ceremonies and rules which were laid long ago by Chingiz Khan.

For each clan a place was fixed in battle-array. One of their ceremonies was acclamation

of nine standards which is thus described by Babur:

"The

standards were acclaimed in Mughal fashion. The Khan dismounted and nine

standards were set up in front of him. A Mughal tied a long strip of white

cloth to the thigh-bone of a cow and took the other end in his hand. Three

other long strips of white cloth were tied to the staves of three of the nine

standards, just below the yak-tails, and their other ends were brought for the

Khan to stand on one and for me and SI. Muh. Khanika to stand each one of the

two others. The Mughal who had hold of the strip of cloth fastened to the cow's

leg, then said something in Mughal while he looked at the standards and made

signs towards them. The Khan and those present sprinkled quiniz in the

direction of the standards; hautbois and drums were sounded towards them ; the

army flung the war-cry out three times towards them, mounted, cried it again

and rode at the gallop round them."

This

incident relates to 1502 A.D. and took place at Bish-lcint on the Khujand-Tashkent

road. Babur is standing on a strip of white cloth. In the foreground is an old

Mughal soldier holding a piece of cloth which he has tied to the leg of a cow.

In the background trumpets are being sounded and drums beaten.

KHUSRAU SHAH PAYING HOMAGE TO BABUR AT DOSHI NEAR KABUL

Khusrau

Shah, a Turkistani Qipchaq, was a noble of Mahrmad Mirth' who ruled the country

from Amu to the Hindukush mountains. Babur describes him as 'black-souled and

vicious, dunder-headed and senseless, disloyal, traitor, and a coward who had

not the pluck to stand up to a hen!' He met Babur at Dashi near Kabul. Babur

thus describes their meeting:

Khusrau

Shah, a Turkistani Qipchaq, was a noble of Mahrmad Mirth' who ruled the country

from Amu to the Hindukush mountains. Babur describes him as 'black-souled and

vicious, dunder-headed and senseless, disloyal, traitor, and a coward who had

not the pluck to stand up to a hen!' He met Babur at Dashi near Kabul. Babur

thus describes their meeting:

"Next

day, one in the middle of the First Rabi (end of August, 1504 A.D.), riding

light, I crossed the Andar-ãb water and took my seat under a large plane-tree

near Dashi, and thither came Khusrau Shah, in pomp and splendour, with a great

company of men. According to rule and custom, he dismounted some way off and

then made his approach. Three times he knelt. When we saw one another, three

times also on taking leave; he knelt once when asking after my welfare, once

again when he offered his tribute, and he did the same with Jahangir Mirza and

with Mirza Khan (Wais)."

Babur

is seated under a plane-tree and the person kneeling in front of him is Khusrau

Shah. In the foreground are his retainers including one holding a hawk. After

receiving homage from Khusrau Shah Babur marched to Kabul.

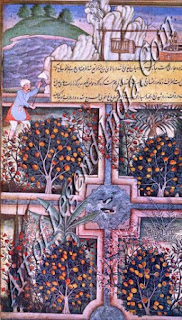

THE GARDEN OF FIDELITY NEAR KABUL (BAGH-I-WAFA)

Artist, Bhagwan

With

the capture of Kabul in 1504 begins the second phase in the career of Babur.

Kabul is known for its temperate fruits, viz, the grape, pomegranate, apricot,

apple, pear, peach, plum and walnut. In the hotter valleys, even sugarcane,

orange and citron were cultivated. Now that he had some peace, he indulged in

his favourite hobby of gardening. In 1508-9 he laid out a garden known as

Bagh-i-wafa near Fort Adinapur, which he thus describes:

"The

garden lies high, has running-water close at hand, and a mild winter climate.

In the middle of it, a one-mill stream flows constantly past the little hill on

which are the four garden-plots. In the south-west part of it there is a

reservoir, 10 by 10, round which are orange-trees and a few pomegranates, the

whole encircled by a trefoil-meadow. This is the best part of the garden, a

most beautiful sight when the oranges take colour. Truly that garden is

admir-ably situated !"

On the

top of the painting is Koh-i-Safed, the snow-covered mountain, and a persian

wheel for lifting water. Below is the Char-bagh divided into four plots in

which oranges are growing. A plantain and two cypresses grow in one of the

plots. A keord plant is in the plot on the top right. In the reservoir in the

centre a pair of ducks are gambolling. A solitary gardener is digging the soil

in the plot to the left.

Maur

thus records a visit to Kigh-i-wafd in A.D. 1519. "We dismounted in the

Bligh-i-wafd; its oranges had yellowed beautifully; its spring-bloom was

well-advanced, and it was very charming."

BABUR SUPERVISING THE CONSTRUCTION OF A RESERVOIR ON THE SPRING OF `KHWAJA SIH YARAN', NEAR KABUL

Artist, Prem

Babur

describes the pleasant villages around Kabul and their gardens. He records

thirty three different varieties of tulips on the foothills of Dasht-i-Shaikh.

In the ranges of Pamghan were a number of villages which grew grapes. Of these

he admired Istalif as the best of the lot.

Babur

describes the pleasant villages around Kabul and their gardens. He records

thirty three different varieties of tulips on the foothills of Dasht-i-Shaikh.

In the ranges of Pamghan were a number of villages which grew grapes. Of these

he admired Istalif as the best of the lot.

"Few

villages match Istalif", wrote Babur, "with vineyards and fine

orchards on both sides of its great torrent, with waters needing no ice, cold

and, mostly, pure. Of its Great garden Aulugh Beg Mirza had taken forcible

possession; I took it over, after paying its price to the owners. There is a

pleasant halting-place outside it, under great planes, green, shady and

beautiful. A one-mill stream, having trees on both banks, flows constantly

through the middle of the garden; formerly its course was zig-zag and

irregular; I had it made straight and orderly; so the place became very

beautiful.

"I

ordered that the spring should be enclosed in mortared stone-work, 10 by 10,

and that a symmetrical, right-angles platform should be built on each of its

sides, so as to overlook the whole field of Judas trees. In, the world over,

there is a place to match this when the arghwans are in full bloom, I do not

know it. The yellow arghwiin grows plentifully there also, the red and the

yellow flowering at the same time.

"In

order to bring water to a large round seat which I had built on the hillside

and planted round with willows, I had a channel dug across the slope from a

half-mill stream, constantly flowing in a valley to the south-west of Sih-ydran.

The date of cutting this channel was found in jui-khush (kindly-channel)."

In this

colourful painting Babur holding a hawk is standing near the reservoir, which

he got constructed. In the background is his tent. On the top of the painting the artist has painted a dancing peacock, tail spread out into a gorgeous fan,

admired by a pair of pea-hens. Surely it is a reminder of India, the home of

the painter. On the rocks are a pair of mountain goats. In the foreground a

grey-hound is drinking water from the stream. It is undoubtedly one of the most

delightful paintings of the Babur.

BIRD CATCHING AT BARAN

Artist, Bhag

Babur Nama is in Kohistan province of Afghanistan. Babur wrote, "More beautiful in

Spring than any part even of Kabul are the openlands of Baran and the skirt of

Gul-i-bahar. Many sorts of tulips bloom there.

Babur Nama is in Kohistan province of Afghanistan. Babur wrote, "More beautiful in

Spring than any part even of Kabul are the openlands of Baran and the skirt of

Gul-i-bahar. Many sorts of tulips bloom there.

Kabul

in Spring is an Eden of verdure and blossom Matchless in Kabul the Spring of

Gul-i-bahar and Baran Few places are equal to these for spring excursions for

hawking or bird-shooting.

"Along

the Baran people take masses of cranes (tarnii) with the cord ; masses of

afiqdr, qargarii and qatan also. This method of bird catching is unique. They

twist a cord as long as the arrow's flight, tie the arrow at one end and a

bildfirgii at the other, and wind it up, from the arrow-end, on a piece of

wood, span-long and wrist-thick, right up to the bildfirgii. They then pull out

the piece of wood, leaving just the hole it was in. The bildfirgei being held

fast in the hand, the arrow is shot off towards the coming flock. If the cord

twist round a neck or wing, it brings the bird down. On the Baran everyone

takes birds in this way." By this device Baran people catch the many

herons from which they take the turban-aigrettes sent from Kabul for sale in

Khurasan.

"Of

bird-catchers there is also the band of slave-fowlers, two or three hundred

house-holds, whom some descendant of Timm-Beg made to migrate from near Multan

to the Baran. Bird-catching is their trade; they dig tanks, set decoy-birds on

them, put a net over the middle, and in this way take all sorts of birds."

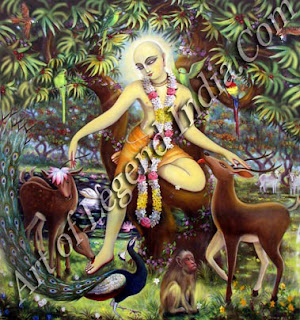

This

painting by Bhag is one of the best studies of birds in the Babur Nama. Outside

the net set by the fowler who is hiding behind a screen are a pair of hoopoes,

sarus cranes, snipes and other water-birds. A sarus crane is innocently flying

into the net. In the foreground is a mountain stream with lotuses among whom

ducks are gambolling, providing a poetic touch to this painting.

BABUR FEASTING AT KOHAT

Artist, Daulat

"Whether

to cross the water of Sind, or where else to go, was discussed in that camp.

Baqi Chaghaniani represented that it seemed we might go, without crossing the

river and with one night's halt, to a place called Kohat where were many rich

tribesmen; moreover he brought Kabulis forward who represented the matter just

as he had done. We had never heard of the place, but, as he, my man in great

authority, saw it good to go to Kohat and had brought forward support of his

recommendation."

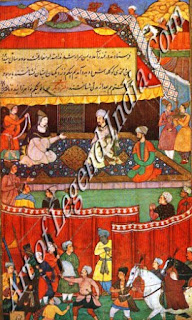

STAGE SET FOR A MEETING BETWEEN BABUR AND THE MIRZAS

This

painting relates to a meeting between Babur and the Mirzas of Khurdsdn on 26th

October, 1506, on the Murghab river. About the Mirzds, Babur comments, 'They

were good enough as company and in social matters, but they were strangers to

war, strategy, equipment, bold fight and encounter.' He thus describes this

meeting:

This

painting relates to a meeting between Babur and the Mirzas of Khurdsdn on 26th

October, 1506, on the Murghab river. About the Mirzds, Babur comments, 'They

were good enough as company and in social matters, but they were strangers to

war, strategy, equipment, bold fight and encounter.' He thus describes this

meeting:

"Four

divans (tushuk) had been placed in the tent. Always in the Mirzd's tents one

side was like a gate-way and at the edge of this gate-way he always sat. A

divan was set there now on which he and Muzaffar Mirza sat together. Abu'l

muhsin Mirzd and I sat on another, set in the right-hand place of honour (tur).

On another, to Badiuz zamdn Mirza's left, sat Ibn-i-husain Mirza with Qasim SI.

Auzbeg, a son-in-law of the late Mirza and father of Qasim-i-husain Sultan. To

my right and below my divan was one on which sat Jahangir Mirza and

Abdu'r-razzaq Mirza. To the left of Qdsim SI. and Ibn-i-husain Mirld, but a

good deal lower, were Muh. Baranduq Beg, Zu'n-nun Beg and Qasim Beg.

Although

this was not a social gathering, cooked viands were brought in, drinks were set

with the food, and near them gold and silver cups."

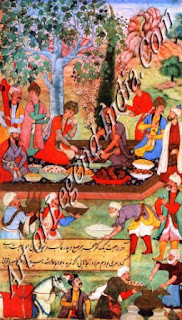

BABUR ENJOYING A FEAST GIVEN BY THE MIRZAS AT HERAT

In 1507

Babur paid a visit to Herat. Here he saw the gardens, mosques and mausolea

including Gazur-gah, the tomb of Khwaja Abdullah Ansari. Here he married Masrima-Sultan

Begam. The Mirzds entertained Babur at a feast.

In 1507

Babur paid a visit to Herat. Here he saw the gardens, mosques and mausolea

including Gazur-gah, the tomb of Khwaja Abdullah Ansari. Here he married Masrima-Sultan

Begam. The Mirzds entertained Babur at a feast.

"Bad! Uzi-zaman Mirza asked me to a party arranged in the Maqauwi-khana of the

world-adorning Garden. He asked also some of my close circle, and some of our

braves.

"At

this party they set a roast goose before me but as I was no carver or

disjointer of birds, I left it alone. 'Do you not like it?' inquired the Mirza.

Said I, 'am a poor carver.' On this he at once disjointed the bird and set it

again before me. In such matters he had no match. At the end of the party he

gave me an enamelled waist-dagger, a char-qab, and a tipu-chaqt."

This is

a beautiful painting showing a feast in a garden, under the shade of a chenart.

Cooks are busy cooking in the foreground and attendants are carrying food.

Babur is making a futile attempt to carve a goose, while Badi-u'z-zaman Mirza

is looking on and is about to intervene.

BABUR CAPTURES A FLOCK OF SHEEP FROM THE HAZARAS

After

seeing the sights of Herat, Babur left for Kabul. Instead of travelling by the

Kandahar road which though longer, was safe and easy, he took the mountain-road

which was difficult and dangerous. During the night there was heavy snow-fall

and a blizzard. He took shelter in a cave along with his men. Next morning

while he was on the move a body of Turkman Hazards attacked his army with

arrows.

After

seeing the sights of Herat, Babur left for Kabul. Instead of travelling by the

Kandahar road which though longer, was safe and easy, he took the mountain-road

which was difficult and dangerous. During the night there was heavy snow-fall

and a blizzard. He took shelter in a cave along with his men. Next morning

while he was on the move a body of Turkman Hazards attacked his army with

arrows.

"I

myself collected a few of the Hazards' sheep, gave them into Yarak Taghai's

charge, and went to the front. By ridge and valley, driving horses and sheep

before us, we went to Timur Beg's Langar and there dismounted. Fourteen or

fifteen Hazard theives had fallen into our hands; I had thought of having them

put to death when we next dismounted, with various torture, as a warning to all

high-waymen and robbers, but Qdsim Beg came across them on the road and, with

mistimed compassion, set them free."

In this

painting we see Babur on horse-back and in front of him is a flock of sheep

captured from the Hazards.

BABUR AND COMPANIONS WARMING THEMSELVES BEFORE A CAMP FIRE

While

Babur was raiding the Turkman Hazards, news came that his nobles in Kabul had

mutinied and had declared Miria Khan as Padshdh. They also spread a rumour that

the Mirzas of Herat had captured Babur and imprisoned him in a fort. On the way

to Kabul he encountered intense cold. As he describes:

While

Babur was raiding the Turkman Hazards, news came that his nobles in Kabul had

mutinied and had declared Miria Khan as Padshdh. They also spread a rumour that

the Mirzas of Herat had captured Babur and imprisoned him in a fort. On the way

to Kabul he encountered intense cold. As he describes:

"We

sent on Ahmad the messenger (yasilwal) and Qara Ahmad Yuninchi to say to the

Begs, 'Here we are at the time promised; be ready! behold!' After crossing

Minar-hill and dismounting on its skirt, helpless with cold, we lit fires to

warm ourselves. It was not time to light the signal-fire; we just lit these

because we were helpless in that mighty cold." Next morning he reached

Kabul and subdued the rebels.

This

painting of a night scene shows Babur's qualities of leadership; his concern

for his men and comradely treatment he gave them in times of adversity.

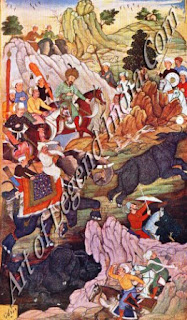

BATTLE SCENE NEAR MURGHAN KOH

Artist, Makra

Shaibaq

Khan, Uzbek captured Herat in June 1507. The Mirzas supplicated Babur for help.

Babur pushed on towards Kandahar. The Uzbeks were led by Shah Beg and his

younger brother Muqim. This painting shows a battle near Kandahar. Babur

states:

Shaibaq

Khan, Uzbek captured Herat in June 1507. The Mirzas supplicated Babur for help.

Babur pushed on towards Kandahar. The Uzbeks were led by Shah Beg and his

younger brother Muqim. This painting shows a battle near Kandahar. Babur

states:

"We

mean time, after putting our adversary to flight, had crossed those same

channels towards the naze of Murghan-koh (Birds'-h ill). Someone on a grey

horse was going backwards and forwards irresolutely along the hill-skirt, while

we were getting across; I likened him to Shah Beg; seemingly it was he.

"Our

men having beaten their opponents, all went off to pursue and unhorse them.

Remained with me eleven to count, `Abdu'l-lah the librarian being one. Muqim

was still keeping his ground and fighting. Without a glance at the fewness of

our men, we had the nagarets sounded and, putting our trust in God, moved with

face set for Muqim." After this incident Babur moved on to Kandahar, and

looted the treasury.

It is

an excellent painting which conveys the excitement of a battle. It is packed

with action, and is symbolic of the restless energy of Babur. Babur holding a

naked sword is charging the enemy. Facing him is Muqim holding a shield. Drums

are being lustily beaten by the drummers of both sides.

BABUR CROSSING A RIVER SEATED ON A RAFT

In May

1508 Babur abandoned the invasion of Hindustan. He visited Lamghanat which

borders the land inhabited by Kafirs, who had resisted conversion to Islam.

Here he crossed a river seated on a raft for the first time. Thus states BAbur:

In May

1508 Babur abandoned the invasion of Hindustan. He visited Lamghanat which

borders the land inhabited by Kafirs, who had resisted conversion to Islam.

Here he crossed a river seated on a raft for the first time. Thus states BAbur:

"As

it was not found desirable to go on into Hindustan, I sent Mulla Baba of

Pashaghar back to Kabul with a few braves. Mean time I marched from near

MandrAwar to Mar and Shiwa and lay there for a few days. From Atar I visited

Kanar and Nurgal; from Kfinar I went back to camp on a raft; it was the first

time I had sat on one; it pleased me much, and the raft came into common use

thereafter."

The

naked swimmers are pushing the raft with all their might. On the raft Babur is

calmly seated surrounded by his body-guards.

On 6th

March, 1506, Babur's first son Htunayun was born in the citadel of Kabul. A

feast was arranged in the Chdr-Bagh. All the Begs brought presents, and dancers

entertained the party.

DEER HUNTING IN 'ALI-SHANG AND ALANGAR MOUNTAINS

Artist, Tulsi

This

painting by Tulsi, who specializes in drawing animals, depicts a hunting scene

in Afghanistan. Apart from deer of different varieties, rabbits, foxes and wild

sheep are also depicted. On a rock a chakor is perching. Babur describes this

event as follows:

This

painting by Tulsi, who specializes in drawing animals, depicts a hunting scene

in Afghanistan. Apart from deer of different varieties, rabbits, foxes and wild

sheep are also depicted. On a rock a chakor is perching. Babur describes this

event as follows:

"On

Saturday (29th) we hunted the hill between 'Ali-shang and Alangair. One

hunting-circle having been made on the 'Ali-shang side, another on the Alangar,

the deer were driven down off the hill and many were killed. Returning from hunting,

we dismounted in a garden belonging to the Maliks of Alangar and there had a

party."

'Ali-shang

and Alangar are mountainous districts of Afghanistan bordering the Hindu-kush,

inhabited by Kafirs who retained their old religion and did not embrace Islam.

Babur describes that trees cover the banks of the streams of 'Ali-Shang and

Alangdr below the fort. The fort shown in the painting is probably the same. He

also mentions that the valley grows grapes, green and red, all trained on

trees.

As a

study of fauna of Afghanistan, this painting has considerable value. It also

conveys the excitement of a hunt most vividly.

BABUR HUNTING RHINOCEROS NEAR BIGRAM (PESHAWAR)

This

painting describes a hunting scene dated 10th December, 1526 near Bigram

(Pesha-war). Babur crossed the river Siyalh-fib, and formed a hunting circle

down-stream. He records.

This

painting describes a hunting scene dated 10th December, 1526 near Bigram

(Pesha-war). Babur crossed the river Siyalh-fib, and formed a hunting circle

down-stream. He records.

"After

a little, a person brought word that there was a rhino in a bit of jungle near

Bigram, and that people had been stationed near-about it. We betook ourselves,

loose rein, to the place, formed a ring round the jungle, made a noise, and

brought the rhino out, when it took its way across the plain. Humdyun and those

come with him from that side (Tramoun-tana), who had never seen one before,

were much entertained. It was pursued for two miles; many arrows were shot at

it; it was brought down without having made a good set at manor horse. Two

others were killed. I had often wondered how a rhino and an elephant would

be-have if brought face to face; this time one came out right in front of some

elephants the mahauts were bringing along, it did not face them when the

mahauts drove them towards it, but got off in another direction."

In the

sixteenth century rhinos were found as far north as Peshawar and Sind. Now they

are no longer to be seen in these areas. At present rhinos are preserved in the

game sanctuaries of Assam and northern Bengal.

THE BATTLE OF PANIPAT

Babur

invaded India for the fifth time in 1525. He defeated Daulat Khan Lodi and

occupied Punjab. He marched through Jaswan dun, Rapar, Banur, Arnbala,

Shahabad, and reached Panipat on 12th April, 1525. He collected seven hundred

carts, which were joined togehter with ropes of raw hide. Between every two

carts mantelets were fixed, behind which matchlockmen were posted. Opposing him

was Ibrahim Lodi's army of 1,00,000 men and one thousand elephants. Mustafa,

his commander of artillery made excellent use of his guns.

Babur

invaded India for the fifth time in 1525. He defeated Daulat Khan Lodi and

occupied Punjab. He marched through Jaswan dun, Rapar, Banur, Arnbala,

Shahabad, and reached Panipat on 12th April, 1525. He collected seven hundred

carts, which were joined togehter with ropes of raw hide. Between every two

carts mantelets were fixed, behind which matchlockmen were posted. Opposing him

was Ibrahim Lodi's army of 1,00,000 men and one thousand elephants. Mustafa,

his commander of artillery made excellent use of his guns.Babur records,

"Mustafa

the commissary for his part made excellent discharge of zarb-zan shots from the

left hand of the centre. Our right, left, centre and turning-parties having

surrounded the enemy rained arrows down on him and fought ungrudgingly. He made

one or two small charges on our right and left but under our men's arrows, fell

back on his own centre. His right and left hands (qui) were massed in such a

crowd that they could neither move forward against us nor force a way for

flight.

"When

the incitement to battle had come, the Sun was spear-high; till mid-day

fighting had been in full force; noon passed, the foe was crushed in defeat,

our friends rejoicing and gay. By God's mercy and kindness, this difficult

affair was made easy for us!"

Ibrahim

lay dead among thirty thousand of his soldiers, and Babur emerged the winner.

The

painting shows the battle-scene. Between the guns, soldiers armed with bows and

arrows are making sallies. It is surprising that hills are shown in the background.

The battle-field of Panipat is a flat plain. Drummers are beating drums to

infuse courage among the attackers. On the top of the painting is shown the

town of Panipat

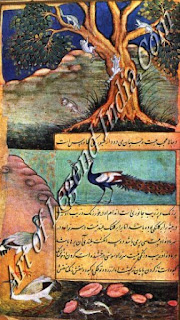

SQUIRRELS, A PEACOCK AND A PEA-HEN, SARUS CRANES AND FISHES

Artist, Bhawani

Babur

appropriately starts his account of the birds of India with the peacock, the

national bird of India.

Babur

appropriately starts his account of the birds of India with the peacock, the

national bird of India.

"The

peacock (Ar. Taus) is a beautifully coloured and splendid bird. Its form

(andam) is not equal to its colouring and beauty. Its body may be as large as

the crane's (tüawa) but it is not so tall. On the head of both cock and hen are

20 or 30 feathers rising some 2 or 3 inches high. The hen has neither colour

nor beauty. The head of the cock has an iridescent collar (tauq sfisani); its

neck is of a beautiful blue; below the neck, its back is painted in yellow,

parrot-green, blue and violet colours. The flowers on its back are much the

smaller; below the back as far as the tail-tips are larger flowers painted in

the same colours. The tail of some peacocks grows to the length of a man's

extended arms. It has a small red tail, under its flowered feathers, like the

tail of other birds. Its flight is feebler than the pheasants; it cannot do

more than one or two short flights. Hindustani call the peacock mor."

This

painting is by Bhawani, who excels in painting birds and animals. On the top

squirrels are playing on a tree. In the middle, a peacock and a pea-hen are

shown, below a pair of sarus cranes, and in the pond a pair of fishes. It is

one of the best paintings of birds and animals in this Babur Nama.

BABUR CROSSING THE RIVER SON OVER A BRIDGE OF BOATS

Artist, Jagnath

This

painting depicts an incident which took place on 14th April, 1529 when Babur

marched through Bihar and crossed the river Son by a bridge of boats. He had

given names to the prominent boats; a large one built in Agra was named Araish

(Repose). Another presented by Araish Khan was named Araish (Ornament).

Another large-sized one was named Gunjaish (Capacious). In it he had another

platform set up, on the top of the one already in it. To a little skiff was

given the name of Farmaish (Commissioned). Babur thus narrates this incident:

"I

left that ground by boat on Thursday. I had already ordered the boats to wait,

and on getting up with them, I had them fastened together abreast in line.

Though all were not collected there, those there were greatly exceeded the

breadth of the river. They could not move on, however, so-arranged, because the

water was here shallow, there deep, here swift, there still. A crocodile (gharial)

shewing itself, a terrified fish leaped so high as to fall into a boat; it was

caught and brought to me."

Babur

is sitting on the platform of the Gunjaish, surrounded by attendants. In the

fore-ground is a boat into which, a fish has leapt. Two soldiers armed with

muskets are firing at the crocodile. All the on-lookers are sharing the

excitement which the incident has provided.

Writer – M.S. Randhawa

Unlike the widely scattered

courts of Rajasthan, the numerous minor Rajput kingdoms of the Himalayan

foothills were clustered in an area only three hundred miles long by a hundred

wide. Although they shared a similar cultural background to the southern Rajput

courts, they were effectively separated from them by the broad expanse of the

Punjab plains, and they were also less affected by Mughal incursions. This

comparative isolation, together with the closer communications between the Hill

courts, contributed to the development of some of the most expressive styles of

Indian painting, characterised in their earlier phases by a controlled

vehemence of colour and line, and later by a mellifluous idiom that combined

Mughal technique with Rajput devotional and romantic sensibility.

The origins of the first

classic style of Pahari (Hill) painting, associated with the court of Basohli,

are still not understood, though it may have had antecedents in the widespread

pre-Mughal style as well as in local Hill idioms. An early illustration to the

Rasamanjari, a poetical text classifying lovers and their behaviour, reveals a

fully formed and highly charged style, with a taut line and vibrant palette.

The interpretation of literary conceits is as direct as in Rajasthani

manuscripts.

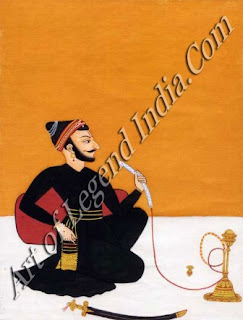

A lady who has been secretly unfaithful explains to her confidante

that the love-marks on her breast were in fact scratches caused by the

household cat as it chased a rat during the night. The cat and the rat appear

on the pavilion roofer here is nothing here of the hybrid weakness sometimes

found in Rajasthani work affected by Popular Mughal fluence. So confident was

the Pahari artists' vision that Mugha portraiture could be reinterpreted with

equal intensity. The Mankot raja with a rosary, huqqa and sword is not a

psychological study of an individual but a celebration of the proud Rajput type

silhouetted against a hot yellow background, orange bolster and white

floorsprcad. Painting at the court of Kulu had a particular wildness and zest, Kuutala

raga, from an extended ragamala series of the Pahari type, is depicted as a

prince feeding pigeons; Akbar himself had been fond of the sport of

pigeon-flying, which was known as ishq-bazi or love-play'.

A lady who has been secretly unfaithful explains to her confidante

that the love-marks on her breast were in fact scratches caused by the

household cat as it chased a rat during the night. The cat and the rat appear

on the pavilion roofer here is nothing here of the hybrid weakness sometimes

found in Rajasthani work affected by Popular Mughal fluence. So confident was

the Pahari artists' vision that Mugha portraiture could be reinterpreted with

equal intensity. The Mankot raja with a rosary, huqqa and sword is not a

psychological study of an individual but a celebration of the proud Rajput type

silhouetted against a hot yellow background, orange bolster and white

floorsprcad. Painting at the court of Kulu had a particular wildness and zest, Kuutala

raga, from an extended ragamala series of the Pahari type, is depicted as a

prince feeding pigeons; Akbar himself had been fond of the sport of

pigeon-flying, which was known as ishq-bazi or love-play'.

A lady who has been secretly unfaithful explains to her confidante

that the love-marks on her breast were in fact scratches caused by the

household cat as it chased a rat during the night. The cat and the rat appear

on the pavilion roofer here is nothing here of the hybrid weakness sometimes

found in Rajasthani work affected by Popular Mughal fluence. So confident was

the Pahari artists' vision that Mugha portraiture could be reinterpreted with

equal intensity. The Mankot raja with a rosary, huqqa and sword is not a

psychological study of an individual but a celebration of the proud Rajput type

silhouetted against a hot yellow background, orange bolster and white

floorsprcad. Painting at the court of Kulu had a particular wildness and zest, Kuutala

raga, from an extended ragamala series of the Pahari type, is depicted as a

prince feeding pigeons; Akbar himself had been fond of the sport of

pigeon-flying, which was known as ishq-bazi or love-play'.

A lady who has been secretly unfaithful explains to her confidante

that the love-marks on her breast were in fact scratches caused by the

household cat as it chased a rat during the night. The cat and the rat appear

on the pavilion roofer here is nothing here of the hybrid weakness sometimes

found in Rajasthani work affected by Popular Mughal fluence. So confident was

the Pahari artists' vision that Mugha portraiture could be reinterpreted with

equal intensity. The Mankot raja with a rosary, huqqa and sword is not a

psychological study of an individual but a celebration of the proud Rajput type

silhouetted against a hot yellow background, orange bolster and white

floorsprcad. Painting at the court of Kulu had a particular wildness and zest, Kuutala

raga, from an extended ragamala series of the Pahari type, is depicted as a

prince feeding pigeons; Akbar himself had been fond of the sport of

pigeon-flying, which was known as ishq-bazi or love-play'.

Although there is some evidence

of strongly Mughal-influenced work in the Hills in the late 17th century,

comparable to that of the Bikaner school, this was exceptional during the first

phase of Pahari painting. But in the second quarter of the 18th century

a fundamental change of direction took place. Artists trained in the Mughal

style began to arrive in increasing numbers, particularly after the sack of

Delhi in 1739. From being the vehicle of a jaded sensuality, their technique

became revitalised in lyrical depictions of Hindu poetical and devotional

subjects, in a development paralleled in Rajasthan by the less subtle

Kishangarh style.

Members of the family of the

artist Pandit Seu, who were based at Guler but travelled widely among the Hill

courts, were influential in shaping and disseminating the new style. One of

Seu's sons was the great portrait artist Nainsukh, who had probably received

some Mughal training. He enjoyed an unusually intimate and understanding

relationship with his patronkthe minor prince Balwant Singh, whom he portrayed

carrying out all the daily activities of a nobleman: hunting, listening to

music, inspecting a horse, or simply writing a letter or preparing to go to

bed. Compared with the stark Mankot picture, Nainsukh's portraiture and spatial

setting are far more naturalistic. Nevertheless the bold, geometrical

arrangement of the architecture and back-ground areas remains typically Rajput.

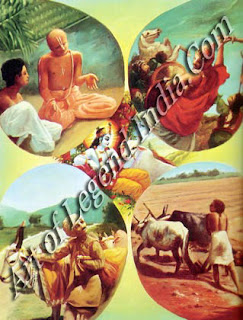

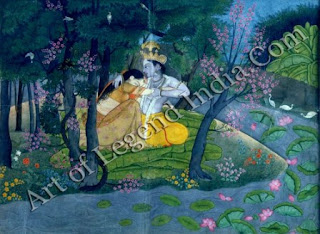

A religious subject in the

early Guler style combines the new technical refinement with a devotional feeling

taking the form of tender domestic observation Shiva is shown sewing a garment,

while Parvati strings human heads for his necklace. Their sons, the many-headed

Karttikcya and the elephant-headed Ganesha, who plays with Shiva's cobra, sit

beside them, and their respective vehicles, the bull, lion, peacock and rat,

wait in attendance Wersions of the graceful Guler idiom were developed at

several courts, such as Garhwal to the south-east, where a Barahmasa

illustration of the winter month of Aghan was painted a pair of lovers, idealised

as Radha and Krishna, gaze at one another on a terrace while two cranes fly

skywards.

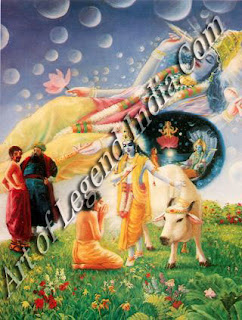

The last great Pahari patron

was Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra (1775-1823), whose long reign saw both the

final maturity of Hill painting and the beginning of its decline. Early in his

reign several masterly series of the classic texts celebrating the life of

Krishna were illustrated for him. The love of Radha and Krishna was depicted

with tender directness in idyllic landscape setting. As in earlier periods of

Indian painting, the luxuriant burgeoning of nature serves to enhance and

express the emotions of the human figures. (Krishna is as usual shown as an

elegant, princely figure; perhaps akin to the young Sansar Chand. As at Guler, scenes

of zenana life were also charmingly rendered, with increasingly curvilinear

rhythms, as in a scene of ladies throwing powder and squirting water at the

spring festival of Holi. But, as at Kishangarh, such a sweetly refined style

could only remain fresh for a short time.

The last great Pahari patron

was Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra (1775-1823), whose long reign saw both the

final maturity of Hill painting and the beginning of its decline. Early in his

reign several masterly series of the classic texts celebrating the life of

Krishna were illustrated for him. The love of Radha and Krishna was depicted

with tender directness in idyllic landscape setting. As in earlier periods of

Indian painting, the luxuriant burgeoning of nature serves to enhance and

express the emotions of the human figures. (Krishna is as usual shown as an

elegant, princely figure; perhaps akin to the young Sansar Chand. As at Guler, scenes

of zenana life were also charmingly rendered, with increasingly curvilinear

rhythms, as in a scene of ladies throwing powder and squirting water at the

spring festival of Holi. But, as at Kishangarh, such a sweetly refined style

could only remain fresh for a short time.  From the beginning of the 19th

century it became facile and sentimental. At the same time, Sansar Chand's

power was lost first to Gurkha invaders and then to the Sikhs, who had won

control of the Punjab plains and now began to annexe the Hill kingdoms.

However, the British traveller William Moorcroft, who visited Sansar Chand in

1820, reports that, though living in reduced circumstances, he was still 'fond

of drawing' and continued to support several artists as well as a zenana of

three hundred ladies. His daily life was still passed in an orderly round of

prayer, conversation, chess, viewing pictures and performances of music and

dance.

From the beginning of the 19th

century it became facile and sentimental. At the same time, Sansar Chand's

power was lost first to Gurkha invaders and then to the Sikhs, who had won

control of the Punjab plains and now began to annexe the Hill kingdoms.

However, the British traveller William Moorcroft, who visited Sansar Chand in

1820, reports that, though living in reduced circumstances, he was still 'fond

of drawing' and continued to support several artists as well as a zenana of

three hundred ladies. His daily life was still passed in an orderly round of

prayer, conversation, chess, viewing pictures and performances of music and

dance.

The Sikhs continued to hold the

Punjab until their displacement by the British in 1849. They commissioned

portraits of their Gurus and themselves in a weakened Pahari manner, to which

they brought little inspiration as patrons. However one of the most imposing of

all Indian portraits is that of Maharaja Gulab Singh. His large figure which

fills the picture area is shown seated holding the familiar props of a sprig of

flowers and a sword. He wears a dextrously composed turban and coat with

sharply ruffled hem, and his face, no longer in profile, stares obliquely away

from the viewer in baleful self-possession.

Writer

– Andrew T0psfield