Tradition with Modernism

Despite his limited subject matter of

portraits and nudes, Modigliani's work was unique in its combination of

traditional form with new painting techniques.

Portraits

and nudes established themselves as Modigliani's subjects from the beginning,

(he painted only a handful of landscapes).

He was not concerned with portraying

realistic appearances, but expressing the feeling and mood of his models,

especially in relation to himself. Most often, in the early part of his career,

tension and anxiety were the recurring motifs, probably echoing those features

in his own life at the time.

Living as a poverty-stricken foreigner in

Paris brought its own insecurities compounded by his feeling of alienation from

the avant-garde artists. His lack of money meant shortage of materials, so his

paint was spread thinly and he had to use both sides of the canvas.

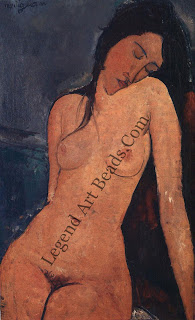

Nonetheless, certain characteristics emerge as trademarks of his style as early

as 1908, fixing his own personal identity as an artist, and these are refined

into the elegance and poise of his last pictures. In his portraits sloping

shoulders and slender necks support gently tilting heads in which small mouths,

long noses and dark, introspective eyes are caught in a hypnotic expression.

|

|

From

Italy, Modigliani carried with him the influences of Symbolism and Stile

Liberty (Art Nouveau) and his early works reflect this in mood and in their

linear pattern.

But in Paris, Modigliani discovered Cezanne at his

retrospective exhibition in 1907, and his debt to Cezanne is revealed in the construction

of his compositions in the arrangement of forms and isolation of planes through

color as well as his choppy brushstrokes. Although Cezanne had opened a new

direction in art leading to Cubism, he had never lost respect for the integrity

of the human form, which became central for Modigliani.

SCULPTURE OUT OF STONE

On

his return from summer in Livorno in 1909, Modigliani had decided to realize

his deep-seated ambition to become a sculptor. This is how he had introduced

himself on his arrival in Paris three years earlier. Between 1909 and 1914 he

produced barely twenty pictures. Inspired by the Rumanian sculptor, Brancusi,

whom he met in 1909 and next to whom he had a studio for a couple of years,

Modigliani was at work during these years on the remarkable heads that

integrate the concern for mass, volume and form that had initially attracted

him to Cezanne. The force of these mysterious faces lies in their inscrutable

expressions, and in their monumentality: one never forgets the rough-hewn

limestone block from which they have emerged. They also show a preoccupation

with the primitive sculptures of Africa and Oceania which Modigliani shared

with his contemporaries.

Modigliani

had always considered himself a painter-sculptor, having made his first

sculpture at Carrara in 1902, symbolically close to the quarries that had

provided Michelangelo with stone. In Paris, he carved the blocks that had been

begged or stolen from building sites. But he had never received any training in

sculpture and possessed neither the discipline nor the strength (the dust

irritated his lungs) to complete his ambitious project to construct a temple to

humanity adorned with pillars in the form of caryatids. Unable to find

materials in wartime, he ceased sculpting in 1914. The experience inevitably

fed his art, giving him a sure sense of form. In fact, his painting began to

take on the characteristics of his sculpture,

Especially

the modelled faces of his last portraits. The regret at this failure must have

cut deep. For in the combination of aggression and finesse that carving

demands, Modigliani may have found the best vehicle for his art of personal

feeling.

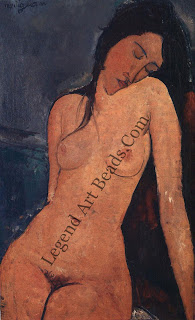

In

his portraits Modigliani showed keen insight into the character of the sitter,

a reflection of his own personal opinion. But his approach to nudes was different

he rarely painted lovers naked. Instead he used unprofessional models,

preferably servant girls. Interestingly, he always painted nudes in series,

showing he was working on them exclusively over a period of time. His nudes are

blatantly sensual and self confident and stand in the tradition of the genre,

alongside those of Titian, Goya and Renoir. Warm colors enhance the sensuous

undulating line that encloses the female form, buffeted by animated

brushstrokes. Unlike his portraits, their facial expressions seem all to be the

same.

His

confident use of line marks out the countless drawings Modigliani made through

his career. They were aide-ntemoires in which interesting compositions were

stored to be reused sometimes years later, although he never dispensed with a

model. Drawing was primarily the preliminary to painting. Jacques Lipchitz

recalled Modigliani making lots of drawings rapidly, seldom stopping 'to

correct or ponder'.

He would familiarize himself with his sitter in this way,

and gradually decide on a pose. When he subsequently turned to the canvas, he

worked quickly, 'interrupting only now and then to drink from a bottle standing

nearby'. His friend Lunia Czechowska noted that he worked best in a rage,

stoked by cheap brandy or rough red wine. The act of painting required an

immense emotional investment from the painter, who would move about, sigh

deeply and cry out in frustration. He worked intensively in order to complete

the picture at only one sitting.

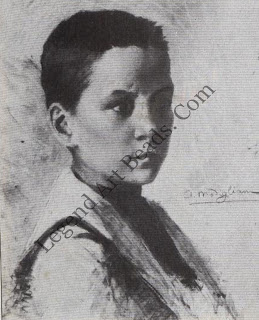

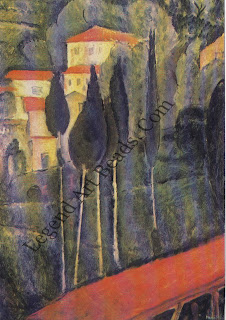

A

year before he died, Modigliani went to the South of France. As models he used

local people and it may be that his impending paternity moved him to use

children as subjects. Here, too, he painted his rare landscapes. All of them

feature houses and trees he seemed to shy away from untouched nature. Despite

his dislike of the Mediterranean outdoors, his paintings during this period

have the airy luminosity of the south.

Modigliani's contribution to modern

art lies in his individuality. Unlike the artists of the avant-garde, for

example Picasso, he was not concerned with fragmenting form but in the

integrity of form in keeping with the tradition of the past. Yet his modernity

is reflected in his use of compositional devices which make his portraits

appear new and unique after all, it is impossible to confuse his work with any

other artists. Having no school, Modigliani has no successors.

THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE

Portrait of Jacques Lipchitz and his Wife

Both

Lipchitz and Modigliani were Jewish, middle class and sculptors, but they do

not appear to have been close friends which the portrait seems to reflect in

the formality of its composition.

In

1916, Lipchitz commissioned a portrait of himself and his new wife, Berthe,

from Modigliani, who informed him, 'My price is ten francs a sitting and a

little alcohol'. To familiarize himself with his sitters, Modigliani made

numerous drawings and the next day, set to work on an old, primed, canvas.

Working intensely, he had finished by the end of the afternoon. Lipchitz wanted

to pay him more, and so asked him to paint more 'substance'. 'If you want me to

spoil it,' came the reply, 'I can continue'. Modigliani gave another fortnight

to the picture.

Lipchitz did not like his portrait and kept it

in a closet until, in 1920, soon after Modigliani's death, he exchanged it for

some of his own earlier sculptures.

Writer-Marshall Cavendish

His

confident use of line marks out the countless drawings Modigliani made through

his career. They were aide-ntemoires in which interesting compositions were

stored to be reused sometimes years later, although he never dispensed with a

model. Drawing was primarily the preliminary to painting. Jacques Lipchitz

recalled Modigliani making lots of drawings rapidly, seldom stopping 'to

correct or ponder'.

His

confident use of line marks out the countless drawings Modigliani made through

his career. They were aide-ntemoires in which interesting compositions were

stored to be reused sometimes years later, although he never dispensed with a

model. Drawing was primarily the preliminary to painting. Jacques Lipchitz

recalled Modigliani making lots of drawings rapidly, seldom stopping 'to

correct or ponder'.

0 Response to "Traditional art with Modernism by Modigliani"

Post a Comment