Introduction to Albrecht Durer

Albrecht

Diirer was the greatest artist of the Northern Renaissance. He experimented in

many media, and is as well-known for his delicate watercolors of animal and

plant life as for the dramatic woodcuts and exquisite engravings on religious

themes which brought him fame in his own time. His art is a blend of Northern

and Southern traditions, profoundly influenced by the Venetian painting he saw

during his visits to the city.

Durer

was an independent man, proud of his appearance and very sure of his talent.

Intelligent and cultured, he mixed with humanists and scholars, while his

patrons included the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. A religious man

throughout his life, in later years he became increasingly preoccupied with the

advent of the Lutheran Reformation. He died in 1528 and was buried in his home

town of Nuremberg.

Albrecht Durer was born on 21 May

1471, in the south German city of Nuremberg. His father, a goldsmith from

Hungary, had married Barbara Holper, his master's daughter, who went on to bear

him eighteen children, of which Albrecht was the third.

As a child, Durer attended a local

Latin school, where he first met Willibald Pirckheimer, a young nobleman, who

was to become a famous Humanist scholar and Dtirer's lifelong friend and

correspondent. For three years after leaving school [hirer followed custom and

studied the goldsmith's trade in his father's workshop. Already he displayed

signs of his wondrous artistic talent. In the memoir he wrote shortly before

his death, Darer recalled: 'My father took special pleasure in me, for he saw

that I was eager to know how to do things and so he taught me the goldsmith's

trade, and though I could do that work as neatly as you could wish, my heart

was more for painting. I raised the whole question with my father, and he was

far from happy about it, regretting all the time wasted, but just the same he

gave in'. the Nuremberg painter Michael Wolgemut, master of the old late

medieval style.

As a child, Durer attended a local

Latin school, where he first met Willibald Pirckheimer, a young nobleman, who

was to become a famous Humanist scholar and Dtirer's lifelong friend and

correspondent. For three years after leaving school [hirer followed custom and

studied the goldsmith's trade in his father's workshop. Already he displayed

signs of his wondrous artistic talent. In the memoir he wrote shortly before

his death, Darer recalled: 'My father took special pleasure in me, for he saw

that I was eager to know how to do things and so he taught me the goldsmith's

trade, and though I could do that work as neatly as you could wish, my heart

was more for painting. I raised the whole question with my father, and he was

far from happy about it, regretting all the time wasted, but just the same he

gave in'. the Nuremberg painter Michael Wolgemut, master of the old late

medieval style.

In 1490, at three years in Wolgemut's studio, Dtirer set off

the traditional German 'bachelor's year', a pen of wandering from city to city

when life could explored before settling down and accepti family

responsibilities.

He travelled through much of what was

the Holy Roman Empire, and after two arrived in Colmar in Alsace, now a Germs

speaking part of France. There he had hoped meet Martin Schongauer, the

greatest Germ engraver of the previous generatic Unfortunately, Schongauer had

died only Mont before Durer's arrival. Nonetheless, he stay with the dead

master's brother and no dot learned from him some of the technical secrets was

later to use in his own work. Darer al worked for publishers in Basel and

Strasboui designing woodcut illustrations for Bibles other books.

In 1493, his father arranged a

marriage for hi with the daughter of a local coppersmith, a 8 named Agnes Frey.

Darer sent home a marvello painted portrait of himself, then aged twenty two

which is the first independent self-portrait painted only for the artist's

personal satisfaction in the whole of European art. In it he appears a handsome

if unusual looking youth, adorned in what today would be called fashionable,

flamboyant clothes, proud of his long blond tresses and even prouder of his

painterly skill. Darer returned to Nuremberg to be married in the spring of

1494. We know little of his wife's personality, though Pirckheimer complained

in later years that she was 'nagging, shrewish, and greedy'.

Within months of

his marriage Durer left his wife in Nuremberg and set off on his first journey

to Italy, using money borrowed from Pirckheimer's family.

JOURNEY TO ITALY

There was plague in Nuremberg at the

time and this may have been the young artist's motive for leaving the city.

Whatever the reason, there can be little doubt that Durer was powerfully

attracted by what he must have heard, during his earlier travels, of the feats

of the new Italian masters of painting and drawing. German artists, he said,

were 'unconscious as a wild, uncut tree', whereas the Italians had rediscovered two hundred years ago the art revered by the Greeks and Romans'.

There were no carriage facilities for

long-distance travel at that time and the journey over the Alps on horseback

must have been a perilous one. On his way Durer recorded his impression of the

mountain scenery in a series of brilliant watercolors. In Pavia he visited

Pirckheimer, who was completing his studies at the great university there, and

through him Outer came to know of the work of the Italian Humanists, whose

scientific curiosity and independence of mind appealed to him strongly.

The highlight of his journey was

Venice. With his unquenchable thirst for knowledge and his customary diligence,

Durer set himself to learn all that contemporary Italian masters could teach

him. He studied the science of perspective and the portrayal of the nude. He

copied the works of Mantegna and other engravers, and argued over the various

theories of art with the sociable circle of Venetian painters.

When he returned home the following

year he brought with him the rudiments of the Italian Renaissance and the

ambition to transplant them to his native northern soil. He made a living from

his woodcuts and engravings, often single sheet designs which his wife and

mother would hawk in the public markets and fairs, and which were carried all

over Europe by the town's travelling merchants.

These were tumultuous years in

central Europe. Many preachers foretold the world would end in the year 1500.

These feelings of doom were brilliantly summed up in Durer's illus-tractions to

The Apocalypse of St. John (1498), his first masterwork.

Although they were printed with a

text at the famous press of his godfather, Anton Koberger, in Nuremberg, Darer

insisted that his own name appear as the publisher. This was part of his

lifelong campaign to raise the status of the artist in northern Europe and to

secure recognition for his own genius. Two years later he painted another

self-portrait, facing the viewer directly in a pose deliberately reminiscent of

Christ .

The portrait displays the pride and self-consciousness of a man

who was by then well aware of his own unique artistic destiny.

In the years that followed, Diirer

slowly digested the lessons of his Italian journey and produced a remarkable

variety of work. Some commissions for painting came in from burghers and

aristocrats, including the powerful Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise. But

it was his woodcuts and increasingly his engravings on copperplate which spread

his fame and earned him the independence he so desperately craved.

In the late summer of 1505 Darer

headed south once again. He had received a commission to paint an altarpiece

for the wealthy association of German merchants in Venice. This time he settled

in the great island city for more than a year. By then his engravings were

well-known in Italy and tributes flowed from other artists as well as from such

eminent men as the Doge and Patriarch of Venice, both of whom visited his

studio. Durer was determined to show the Venetians that he was not only a

clever draughtsman but also a master of colour and paint equal to the enigmatic

Giorgione, whose haunting images were then causing a tremendous stir. It was,

however, the aged Giovanni Bellini, the grand master of the previous

generation, whose work Durer most admired. When the 80-year-old Bellini visited

Diirer in his studio and praised his work, it was a proud moment for the young

German artist, then 35 years of age.

Darer enjoyed Venetian life, the

company of other artists, the food and wine and the beauty of the city. Most of

all he enjoyed the respect accorded by the Italians to their artists, in sharp

contrast to the penny-pinching ways of the German burghers. 'How I shall shiver

for the sun,' he wrote, contemplating his return, 'Here I am a gentleman, at

home a parasite'. However, when Venice offered him two hundred ducats to remain

in its service for a year, he refused, and returned home in January 1507.

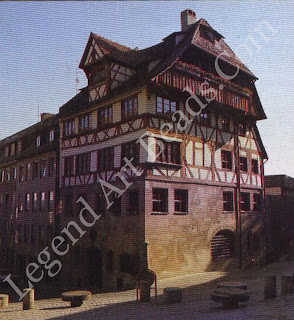

Back in Nuremberg, there were only

few opportunities for any of the large-scale public commissions with which his

Italian rivals made their reputations. Increasingly he abandoned painting and

concentrated on graphic work. His popularity grew and in 1509 he was at last

able to purchase outright the house his family had rented g for some years.

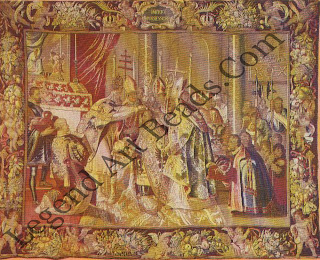

After 1512 he was favored by the Holy Roman 41 Emperor Maximilian I. Darer

decorated a prayer book for him, and collaborated on the creation of the

Triumphal Arch, an enormous composition in the shape of an arch, made up of

hundreds of separate woodcuts. In-1513 Diirer was made an honorary citizen of

the Great Council of Nuremberg, an unprecedented honour for an artist working

north of the Alps, and in 1515 the Emperor granted him an annuity of one

hundred florins for the rest of his life.

Back in Nuremberg, there were only

few opportunities for any of the large-scale public commissions with which his

Italian rivals made their reputations. Increasingly he abandoned painting and

concentrated on graphic work. His popularity grew and in 1509 he was at last

able to purchase outright the house his family had rented g for some years.

After 1512 he was favored by the Holy Roman 41 Emperor Maximilian I. Darer

decorated a prayer book for him, and collaborated on the creation of the

Triumphal Arch, an enormous composition in the shape of an arch, made up of

hundreds of separate woodcuts. In-1513 Diirer was made an honorary citizen of

the Great Council of Nuremberg, an unprecedented honour for an artist working

north of the Alps, and in 1515 the Emperor granted him an annuity of one

hundred florins for the rest of his life.

DIFFICULT YEARS

Despite this public success, these

were difficult years for Darer. Though his income was relatively high, his

expenses quickly offset it. He spent and loaned money freely, filling his house

with strange and precious objects of all kinds. His mother's death in 1514

affected him deeply, and he underwent an artistic and spiritual crisis which is

reflected in his engraving Melencolia He

was still obsessed with the grandeur of the Italian achievements and in

particular with the ideals of beauty and harmony which always seemed to elude

him.

Despite this public success, these

were difficult years for Darer. Though his income was relatively high, his

expenses quickly offset it. He spent and loaned money freely, filling his house

with strange and precious objects of all kinds. His mother's death in 1514

affected him deeply, and he underwent an artistic and spiritual crisis which is

reflected in his engraving Melencolia He

was still obsessed with the grandeur of the Italian achievements and in

particular with the ideals of beauty and harmony which always seemed to elude

him.

In 1517 Martin Luther made his first

great attack on corruption in the Church, thus beginning the upheaval in

European religious life that came to be known as the Reformation. Diirer read

avidly Luther's writings which were passed to him by Reformers such as Philip

Melanchthon, a Humanist scholar who, like Diirer himself, tried to bridge the

gap between the new learning from Italy and the new piety from Germany.

Luther's teachings appear to have brought Durer some relief from his inner

turmoil.

When Emperor Maximilian I died in

1519, the Nuremberg Council stopped Diirer's life pension, prompting his

lengthy journey to the Netherlands to meet the new Emperor and petition for the

renewal of his annuity. He left Nuremberg in 1520, accompanied by his wife and

maidservant. With him he took engravings and woodcuts, with which he was able

to pay his way throughout his trip. He kept a detailed journal in which he

recorded all his expenses and everything he saw or heard, as well as

sketchbooks which he filled with drawings. Everywhere he was received by the

rich and mighty and feted as the greatest German artist of his time. For Darer

it was the fulfillment of his longstanding dream of raising the public status

of the artist.

Along his route Direr made it his

business to see the notable works of art and the important artists in each

town. He made a difficult excursion to Zeeland in the wild north of the country

to see and draw a whale that had been beached there, but by the time he arrived

the creature had already returned to the sea. While in Zeeland, he caught some

kind of fever which was to weaken him for much of the rest of his life. In

Aachen he witnessed the coronation of the new Emperor, Charles V, and when the

court moved to Köln his annuity was confirmed. He painted many portraits and

sold many prints but so indulged his love of collecting including such objects as tortoise-shells,

parrots, coral, conch shells and ivory - that overall he made a financial loss

on the trip.

Darer was in Antwerp when news

arrived of Luther's arrest. He and his wife hurried home, possibly in fear of

attack by pro-Catholic elements in Antwerp. They arrived in Nuremberg in August

1521, to find the city in turmoil. Friends and pupils of Darer's had been

banished for heretical ideas. In the surrounding countryside discontent was

mounting which would eventually explode in the Peasants' War of 1525. Darer,

though careful to remain on the right side of the authorities, nonetheless

expressed some sympathy for the new movements.

In his last great painting, The Four

Apostles, his deep religious feeling was perfectly combined with his love of

Venetian art. He made a gift of the painting to the Council of Nuremberg in 1526,

carefully inscribing it with this warning: 'All worldly rulers in these

dangerous times should pay heed lest they follow' human misguidance instead of

the word of God. For God will have nothing added to his word nor taken away

from it.'

A TIME FOR WRITING

Darer concentrated much of his

strength in his last years on his writings. He published works on proportion,

perspective, and fortification and composed his family chronicle and his

memoirs. He also started, but did not live to finish, a work of advice for

young artists. His old friend Pirckheimer lamented his deteriorating condition:

'He was withered like a bundle of straw and could never be a happy man or

mingle with people'. On 6 April 1528, at the age of 57, in his home city of

Nuremberg, Darer died of the fever he had first contracted in Zeeland. He was

mourned by Melanchthon who described him as a 'wise man whose artistic talents,

eminent as they were, were still.

Writer-Marshall Cavendish

As a child, Durer attended a local

Latin school, where he first met Willibald Pirckheimer, a young nobleman, who

was to become a famous Humanist scholar and Dtirer's lifelong friend and

correspondent. For three years after leaving school [hirer followed custom and

studied the goldsmith's trade in his father's workshop. Already he displayed

signs of his wondrous artistic talent. In the memoir he wrote shortly before

his death, Darer recalled: 'My father took special pleasure in me, for he saw

that I was eager to know how to do things and so he taught me the goldsmith's

trade, and though I could do that work as neatly as you could wish, my heart

was more for painting. I raised the whole question with my father, and he was

far from happy about it, regretting all the time wasted, but just the same he

gave in'. the Nuremberg painter Michael Wolgemut, master of the old late

medieval style.

As a child, Durer attended a local

Latin school, where he first met Willibald Pirckheimer, a young nobleman, who

was to become a famous Humanist scholar and Dtirer's lifelong friend and

correspondent. For three years after leaving school [hirer followed custom and

studied the goldsmith's trade in his father's workshop. Already he displayed

signs of his wondrous artistic talent. In the memoir he wrote shortly before

his death, Darer recalled: 'My father took special pleasure in me, for he saw

that I was eager to know how to do things and so he taught me the goldsmith's

trade, and though I could do that work as neatly as you could wish, my heart

was more for painting. I raised the whole question with my father, and he was

far from happy about it, regretting all the time wasted, but just the same he

gave in'. the Nuremberg painter Michael Wolgemut, master of the old late

medieval style.

Back in Nuremberg, there were only

few opportunities for any of the large-scale public commissions with which his

Italian rivals made their reputations. Increasingly he abandoned painting and

concentrated on graphic work. His popularity grew and in 1509 he was at last

able to purchase outright the house his family had rented g for some years.

After 1512 he was favored by the Holy Roman 41 Emperor Maximilian I. Darer

decorated a prayer book for him, and collaborated on the creation of the

Triumphal Arch, an enormous composition in the shape of an arch, made up of

hundreds of separate woodcuts. In-1513 Diirer was made an honorary citizen of

the Great Council of Nuremberg, an unprecedented honour for an artist working

north of the Alps, and in 1515 the Emperor granted him an annuity of one

hundred florins for the rest of his life.

Back in Nuremberg, there were only

few opportunities for any of the large-scale public commissions with which his

Italian rivals made their reputations. Increasingly he abandoned painting and

concentrated on graphic work. His popularity grew and in 1509 he was at last

able to purchase outright the house his family had rented g for some years.

After 1512 he was favored by the Holy Roman 41 Emperor Maximilian I. Darer

decorated a prayer book for him, and collaborated on the creation of the

Triumphal Arch, an enormous composition in the shape of an arch, made up of

hundreds of separate woodcuts. In-1513 Diirer was made an honorary citizen of

the Great Council of Nuremberg, an unprecedented honour for an artist working

north of the Alps, and in 1515 the Emperor granted him an annuity of one

hundred florins for the rest of his life.  Despite this public success, these

were difficult years for Darer. Though his income was relatively high, his

expenses quickly offset it. He spent and loaned money freely, filling his house

with strange and precious objects of all kinds. His mother's death in 1514

affected him deeply, and he underwent an artistic and spiritual crisis which is

reflected in his engraving Melencolia He

was still obsessed with the grandeur of the Italian achievements and in

particular with the ideals of beauty and harmony which always seemed to elude

him.

Despite this public success, these

were difficult years for Darer. Though his income was relatively high, his

expenses quickly offset it. He spent and loaned money freely, filling his house

with strange and precious objects of all kinds. His mother's death in 1514

affected him deeply, and he underwent an artistic and spiritual crisis which is

reflected in his engraving Melencolia He

was still obsessed with the grandeur of the Italian achievements and in

particular with the ideals of beauty and harmony which always seemed to elude

him.

0 Response to "Albrecht Durer the Great Artist"

Post a Comment