John

Constable, perhaps the greatest and most original of all British landscape

artists, is renowned especially for his views of the Stour Valley in Suffolk,

Salisbury Cathedral and Hampstead Heath. He was brought up in the country, and

out of his deep love for the English landscape grew a determination to record

its beauty: to capture its moistness, light and atmosphere, as well as its

shapes and colours.

Today,

Constable's genius is acknowledged throughout the world, but during his own

lifetime, landscape painting was unfashionable, and the artist was forced to

struggle for recognition. He was 39 before he sold his fast landscape. And

although his magnificent paintings were acclaimed in France, the Royal Academy

in London refused him full membership until 1829 just eight years before his

death.

A Countryman in London

When he chose art as a profession,

Constable left his Suffolk home to live permanently in London. But his bonds

with East Anglia remained strong, and he returned each summer to sketch and

paint.

John

Constable was born in East Bergh°lt in Suffolk on 11 June 1776, the fourth of

his parents' six children. His father Golding was a prosperous corn merchant

who owned wind- and water-mills in East Bergholt and nearby Dedham, together

with land in the village and his own small ship, The Telegraph, which he moored

at Mistley on the Stour estuary and used to transport corn to London. Constable

was brought up with all the advantages of a wealthy, happy home.

John

Constable was born in East Bergh°lt in Suffolk on 11 June 1776, the fourth of

his parents' six children. His father Golding was a prosperous corn merchant

who owned wind- and water-mills in East Bergholt and nearby Dedham, together

with land in the village and his own small ship, The Telegraph, which he moored

at Mistley on the Stour estuary and used to transport corn to London. Constable

was brought up with all the advantages of a wealthy, happy home.

Most of his

'careless boyhood', as he called it, was spent in and around the Stour valley.

After a brief period at boarding school in Lavenham, where the boys received

more beatings than les-sons, he was moved to a day school in Dedham. There the

schoolmaster indulged Constable's interest in drawing, which was encouraged in

a more practical way by the local plumber and glazier, John Dunthorne, who took

him on sketching expeditions.

Golding

Constable was not enthusiastic about his son's hobby, but gave up the idea of

educating him for the church and decided instead to train him as a miller. John

spent a year at this work and, though he never took to the family business, he

did acquire a thorough knowledge of its technicalities. When his younger

brother Abram eventually came to run the business, he often consulted John

about repairs to the mill machinery.

Golding

Constable was not enthusiastic about his son's hobby, but gave up the idea of

educating him for the church and decided instead to train him as a miller. John

spent a year at this work and, though he never took to the family business, he

did acquire a thorough knowledge of its technicalities. When his younger

brother Abram eventually came to run the business, he often consulted John

about repairs to the mill machinery.

FIRST SIGHT OF A MASTERPIECE

Constable's

passion for art was decisively stimulated by Sir George Beaumont, an amateur

painter and art fanatic, whom he met in 1795. Beaumont

owned a

French masterpiece, Hagar and the Angel, by Claude Lorrain, which he took with

him wher-ever he went, packed in a specially-made travel-ling box. The sight of

this picture convinced Const-able of his vocation as an artist. Soon

afterwards, on a trip to London, he began to take lessons from the painter

'Antiquity Smith', an eccentric charac-ter who gave him sound advice and

introduced him to the world of professional painting.

owned a

French masterpiece, Hagar and the Angel, by Claude Lorrain, which he took with

him wher-ever he went, packed in a specially-made travel-ling box. The sight of

this picture convinced Const-able of his vocation as an artist. Soon

afterwards, on a trip to London, he began to take lessons from the painter

'Antiquity Smith', an eccentric charac-ter who gave him sound advice and

introduced him to the world of professional painting.

By 1799

Golding Constable's reluctance to allow his son to pursue his unprofitable and

scarcely re-spectable career was tempered by the fact that a younger brother,

Abram, was showing promise as a miller and businessman. So Constable was

admitted to the Royal Academy Schools and his departure was blessed by his

father with a small allowance.

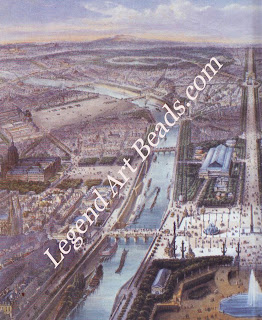

In London

Constable was a hardworking and committed student, who spent his evenings reading

and making drawings, but he was homesick for his friends and family in Suffolk,

and also for its countryside. For a while he shared rooms with another student,

Ramsay Reinagle, who painted his portrait (title page), but Constable became

disgusted with his sly copying of Old Masters and his doubtful dealings in the

art market. His morale. was not improved by the discovery that landscape and

landscape painters were held in very low esteem by the Academy, which only

respected history and portrait painting.

Letters and

baskets of food transported by the family ship kept him in constant contact

with East Bergholt, and he spent many of his summer holidays there, using a

cottage near his parents' house as a studio. He also did some travelling around

England. In 1801 he toured the Peak District in Derbyshire and two years later

made a short sea voyage from London to Deal in Kent aboard an East Indian man.

A LONG, FRUSTRATING COURTSHIP

During the

next seven years the unhappy couple were often parted and sometimes forbidden

even to write, but throughout their long, frustrating courtship they remained

loyal to each other. Con-stable, who felt badly isolated in London, was sustained

by his family, all of whom wished to see him married to Maria, and by the Rev

John Fisher, a nephew of the Bishop of Salisbury, one of his earliest patrons.

Without a strong vein of obstinacy in his character, Constable would not have

survived these difficult years, though they also sharpened his ten-dency to

suffer from depression and moodiness. He gained a reputation for being hostile,

arrogant and sarcastic in his professional dealings, which did not help to sell

his pictures. On the other hand,

John

ConstableeRevd FisheriFitzwilliam Museum with his family and close friends, he

was unfailingly generous and affectionate. In fact, his make-up was in many

ways contradictory. He was, for example, a die-hard reactionary in his

politics, viewing the prospect of Reform with alarm, but in his art he was

distinctly radical.

While

courting Maria, he fell into a regular pattern of work. He would spend the late

autumn, winter and early spring in London, working up his sketches from nature

and preparing his paintings for the Royal Academy exhibition, which opened each

May. Then he would go down to East Bergholt for the summer and early autumn,

escaping the city with relief. In 1815 Mrs. Constable died, which was a great

blow to him. Not long after, Maria's mother died too. These sad events seem to

have strengthened the couple's resolve and by the February of 1816 they had

made up their minds to marry in defiance of all opposition. Then in May,

Constable's father died, sitting peacefully in his chair.

A Lifelong Romance

Constable's

love for Maria Bicknell (right) was a guiding passion in his life. He had known

her since childhood, and the sketch below is thought to be a portrait of Maria

as a young girl. When they fell in love in 1809, Constable's income was meager,

and Maria's family opposed their engagement. The lovers were forced to wait

seven years until he could afford to support them both. And while the marriage

was happy, it was doomed to be short. At the age of 40, Maria died of TB,

leaving a heartbroken husband to bring up their seven young children.

His will,

Abram was to take over the firm and pay John his share of some E200 a year.

Added to his allowance and his earnings from painting, this made marriage

possible at last.

Constable

wrote to Dr Rhudde, seeking his con-sent for the final time. He did not reply,

but confined himself to a frosty bow from his coach, which was reinforced by a

huge grin of congratulation on the face of his coachman above. At the last moment,

Constable astounded Maria by trying to delay the wedding, while he worked on a

painting, but on 2 October they were married in St Martin-in-the-Fields by his

friend Fisher, now an archdeacon. None of the Bicknell family attended.

They enjoyed

a long and happy honeymoon, returning to London in December. By the spring of

the next year Maria was pregnant, having already suffered a miscarriage and

Constable arranged for them to move into larger lodgings. He chose a house in

Keppel Street in Bloomsbury, which appealed to him because it overlooked fields

and ponds. There was even a pig farm near the British Museum to remind them of

Suffolk. In these rustic surroundings their first son was born in 1817.

Marriage and

fatherhood seemed to release in Constable new powers of creativity, and he was

soon at work on his 'six-footers', the large scenes of the River Stour, which

were to become his best-loved masterpieces. The family now enjoyed a settled

way of life, dominated each spring by the exhibition of these big canvases,

which slowly added to the growth of his reputation.

SKETCHES FOR THE HAY WAIN

In 1820 he

began his oil sketch of the picture that was to be The Hay Wain the wain itself

gave him much trouble and he finally had to ask Johnny Dunthorne, the son of

his old friend, to supply him with an accurate drawing. He finished

III the

rxhthhon fiercely to have their pictures hung in prominent positions Constable

chose the large format of his 'six-foot-', canvases to make paintings stand out

aid catch the eye of purchasers.

it in the

April of the following year soon after his second son was born. It has become

his most famous picture, though it made little impact in Eng-land at the time

of its original exhibition, and was eventually bought by a French dealer.

Maria's health had always been delicate and in 1821 Constable settled his

family into a house in Hampstead where the air was cleaner.

For his own use, he

rented a room and a little shed from the village glazier. Standing some 400

feet above the smoke of London, Hampstead was at that time a farming area, with

sand and gravel workings. Along with the Stour valley and Salisbury, it be-came

one of the few landscapes Constable responded to creatively. In 1824 the king

of France awarded him, in his absence, a gold medal for The Hay Wain. And for

the first time his six-footer of the season, The Lock, was bought for the

asking price while on exhibition at the Royal Academy.

MARIA'S TRAGIC ILLNESS

Tragically,

just as it looked as if he might be achieving professional independence, the

first signs of his wife's fatal illness, pulmonary tuberculosis, showed

themselves. To restore her health, he sent her and their young children, now

four in number, to Brighton for the summer. Constable joined them for a few

weeks and painted a number of marine scenes. The next two years saw the birth

of two more children, but no improvement in Maria's health. And the birth, in

January 1828, of her seventh child weakened Maria badly.

In March her father

died, leaving her £20,000 and putting an end at last to their money worries.

But Maria's coughing worsened, she grew feverish at nights and throughout the

summer she wasted away. Maria died on 23 November and was buried in Hampstead.

Constable told his brother Golding, 'I shall never feel again as I have felt,

the face of the world

In March her father

died, leaving her £20,000 and putting an end at last to their money worries.

But Maria's coughing worsened, she grew feverish at nights and throughout the

summer she wasted away. Maria died on 23 November and was buried in Hampstead.

Constable told his brother Golding, 'I shall never feel again as I have felt,

the face of the world

is totally

changed to me'. The marriage for which he had waited so long had lasted a mere

12 years.

He slowly picked up the threads of his professional life. Ironically,

he was elected a full Academician the next February, though by only one vote.

His great rival Turner brought the news, and stayed talking with him late into

the night. In time, new projects began to interest him, notably the publication

of engravings taken from his paintings and oil sketches.

But the period of his

greatest achievements was over. In 1835 he painted The Valley Farm, another

view of Willie Lott's cottage in Flatford, which appears in the Hay Wain. This

was his last major picture of Suffolk. The buyer wanted to know if it had been

painted for anyone in particular. 'Yes sir', Constable told him. 'It is painted

fore very particular person - the person for whom I have all my life painted.'

He died at night on 31 March 1837 and was buried beside Maria in Hampstead.

Writer-Marshall Cavendish

John

Constable was born in East Bergh°lt in Suffolk on 11 June 1776, the fourth of

his parents' six children. His father Golding was a prosperous corn merchant

who owned wind- and water-mills in East Bergholt and nearby Dedham, together

with land in the village and his own small ship, The Telegraph, which he moored

at Mistley on the Stour estuary and used to transport corn to London. Constable

was brought up with all the advantages of a wealthy, happy home.

John

Constable was born in East Bergh°lt in Suffolk on 11 June 1776, the fourth of

his parents' six children. His father Golding was a prosperous corn merchant

who owned wind- and water-mills in East Bergholt and nearby Dedham, together

with land in the village and his own small ship, The Telegraph, which he moored

at Mistley on the Stour estuary and used to transport corn to London. Constable

was brought up with all the advantages of a wealthy, happy home. Golding

Constable was not enthusiastic about his son's hobby, but gave up the idea of

educating him for the church and decided instead to train him as a miller. John

spent a year at this work and, though he never took to the family business, he

did acquire a thorough knowledge of its technicalities. When his younger

brother Abram eventually came to run the business, he often consulted John

about repairs to the mill machinery.

Golding

Constable was not enthusiastic about his son's hobby, but gave up the idea of

educating him for the church and decided instead to train him as a miller. John

spent a year at this work and, though he never took to the family business, he

did acquire a thorough knowledge of its technicalities. When his younger

brother Abram eventually came to run the business, he often consulted John

about repairs to the mill machinery.  owned a

French masterpiece, Hagar and the Angel, by Claude Lorrain, which he took with

him wher-ever he went, packed in a specially-made travel-ling box. The sight of

this picture convinced Const-able of his vocation as an artist. Soon

afterwards, on a trip to London, he began to take lessons from the painter

'Antiquity Smith', an eccentric charac-ter who gave him sound advice and

introduced him to the world of professional painting.

owned a

French masterpiece, Hagar and the Angel, by Claude Lorrain, which he took with

him wher-ever he went, packed in a specially-made travel-ling box. The sight of

this picture convinced Const-able of his vocation as an artist. Soon

afterwards, on a trip to London, he began to take lessons from the painter

'Antiquity Smith', an eccentric charac-ter who gave him sound advice and

introduced him to the world of professional painting.  In March her father

died, leaving her £20,000 and putting an end at last to their money worries.

But Maria's coughing worsened, she grew feverish at nights and throughout the

summer she wasted away. Maria died on 23 November and was buried in Hampstead.

Constable told his brother Golding, 'I shall never feel again as I have felt,

the face of the world

In March her father

died, leaving her £20,000 and putting an end at last to their money worries.

But Maria's coughing worsened, she grew feverish at nights and throughout the

summer she wasted away. Maria died on 23 November and was buried in Hampstead.

Constable told his brother Golding, 'I shall never feel again as I have felt,

the face of the world