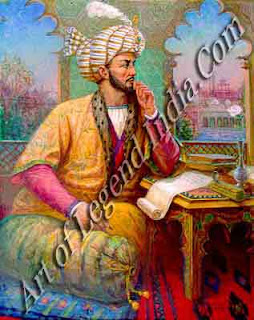

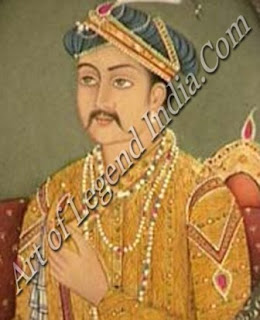

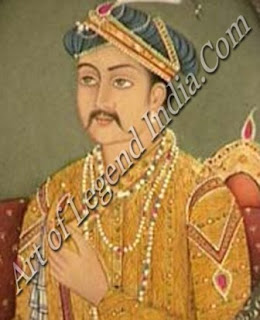

The Babur

Nama reflects the character and interests of the author, Zehir-ed-Din Muhammad Babur. Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty in India, is regarded as one of

the most romantic and interesting personalities of Asian history. He was a man

of indomitable will, a great soldier, and an inspiring leader. But unlike most

men of action he was also a man of letters with fine literary taste and

fastidious critical perception. In Persian, he was an accomplished poet, and in

his mother-tongue, the Turki, he was master of a simple forceful style.

The Babur

Nama reflects the character and interests of the author, Zehir-ed-Din Muhammad Babur. Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty in India, is regarded as one of

the most romantic and interesting personalities of Asian history. He was a man

of indomitable will, a great soldier, and an inspiring leader. But unlike most

men of action he was also a man of letters with fine literary taste and

fastidious critical perception. In Persian, he was an accomplished poet, and in

his mother-tongue, the Turki, he was master of a simple forceful style.

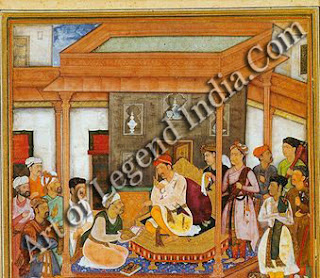

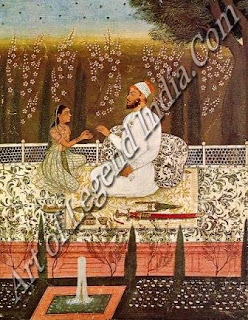

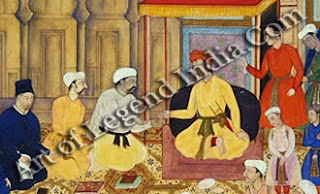

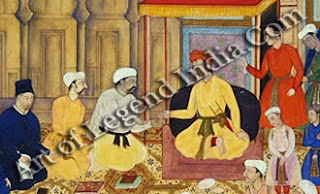

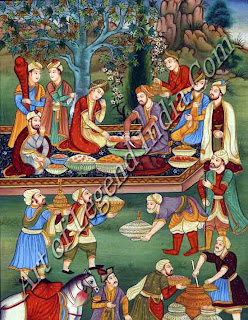

He

was conscious of his own importance and kept a record of his daily activities

in the form of brief notes. He made use of these notes when soon after the

capture of Chanderi on 29 January, 1528; he decided to write his Memoirs. He

chose one of the many gardens around Agra that he had been creating ever since

he had proclaimed himself the padshah of Hindustan and dictated his memoirs,

almost continuously till his death on 26 December, 1530. A painting shows him

dictating his memoirs to a scribe. In less than three years, he succeeded in

giving final form to his autobiography.

At

times Babur was so engrossed in this work that he forgot his surroundings

completely. According to his daughter, Gulbadan, once when he was busy on his

autobiography a storm blew up and the tent in which he was dictating came down

on his head with the result that "sections and book were drenched under

water and gathered together with much difficulty." But he attached such a

great importance to rescuing the papers that he with the help of his daughter

"laid them in the folds of a woolen throne carpet, put this on the throne,

and on it piled blankets and then kindled a fire inspite of the wet" and

occupied himself "till shot of day drying folios and sections."

At

times Babur was so engrossed in this work that he forgot his surroundings

completely. According to his daughter, Gulbadan, once when he was busy on his

autobiography a storm blew up and the tent in which he was dictating came down

on his head with the result that "sections and book were drenched under

water and gathered together with much difficulty." But he attached such a

great importance to rescuing the papers that he with the help of his daughter

"laid them in the folds of a woolen throne carpet, put this on the throne,

and on it piled blankets and then kindled a fire inspite of the wet" and

occupied himself "till shot of day drying folios and sections."

Babur's

autobiography to which he had perhaps himself given the title of Babur Wind was

written "in the purest dialect of the Turki language. It is reckoned among

the most enthralling and romantic works in the literature of all times. It

makes a delightful reading and "deservedly holds a high place in the

history of human literature."

Babur

Nama was preserved as a valuable treasure in the Royal Library by all the five

successors of Babur, who, together with him, are known as the Great Mughals of

Indian history. In fact each one of them showed his adoration for the Nama in

one form or the other. Humayun on ascending the throne ordered All'u-l-Katib to

copy his father's Turki book and see to it that the work was finished in less

than a month and a half. Perhaps not fully satisfied with this hurriedly done

copy, during the next ten years that he held the reins of the Empire, he had

another copy of the Babur Nama prepared.

Humayun carried Babur's original

manuscript with him to exile from 1551 to 1555 and used his leisure moments to

annotate it. Akbar showed his veneration for the book by ordering, Khan-i-Khana

Abdur Rahim to translate it into Persian. Abdur Rahim is recorded to have

finished the assignment in 1589 when he presented to Akbar, its Persian version

under the title Waquit-i-Baburi. Jahangir retouched a copy of the Babur Nama

which he tried to annotate and complete by supplying the missing links. ShahJahan adored the book. Among the select books that he would daily hear being

recited to him before going to sleep was the Babur Nama. Aurangzeb got

inscribed a number of Babur Nam& from the original preserved in the Royal

Library and sent them to many places of importance in his rapidly expanding

empire.

Humayun carried Babur's original

manuscript with him to exile from 1551 to 1555 and used his leisure moments to

annotate it. Akbar showed his veneration for the book by ordering, Khan-i-Khana

Abdur Rahim to translate it into Persian. Abdur Rahim is recorded to have

finished the assignment in 1589 when he presented to Akbar, its Persian version

under the title Waquit-i-Baburi. Jahangir retouched a copy of the Babur Nama

which he tried to annotate and complete by supplying the missing links. ShahJahan adored the book. Among the select books that he would daily hear being

recited to him before going to sleep was the Babur Nama. Aurangzeb got

inscribed a number of Babur Nam& from the original preserved in the Royal

Library and sent them to many places of importance in his rapidly expanding

empire.

It

appears that inspite of a brilliant translation in Persian available since 1589

it was the Turki Babur Nama that held the place of honour in the Royal Library

of the Mughal Emperors. It seems something of an irony, therefore, that its

original should have been lost and unlike the Persian Waquit-i-Baburi should

have been unavailable even in copy to the European scholars when they started

taking interest in Babur's autobiography. It is surmised that the original of

the Babur Nãmä was either destroyed in the sack of Delhi by Nadir Shah in 1739

or burnt during the Mutiny in that city in 1857. The Persian Waquit-i-Baburi,

however, escaped either of those two fates and attracted the attention of the

European indologists. The first European Indologists to be interested in Babur,

as in other personalities of Mughal period of Indian history, were almost all

Scots, e.g. Dr Leyden, William Erskine, John Malcolm and Mountstuart

Elphinstone.

In

the early years of the nineteenth century when the British interest in the

Mughals and their history was acquiring depth, a translation of the Waquit-i-Baburi,

was started by Dr Leyden. He seems to have liked the work and did lot of

jottings from Waquit-i-Baburi when Elphinstone arrived at Calcutta and sent him

the Babur Nama which he had purchased at Peshawar in 1810. The Babur Nãmã in

Turkish slackened Leyden's enthusiasm for the work that he had been doing and

he left the translation of Waquit-i-Baburi only partially done before his death

in 1811. What Leyden had left half done was completed by Erskine. Perhaps

without knowing that Leyden was engaged in the translation of Waquit-i-Baburi,

Erskine had also been busy translating it but just as he was thinking of giving

final touches to his translation, he received all the jottings and papers of

Leyden passed on to him after the latter's death in Java in 1811. The arrival

of Leyden papers forced Erskine to revise the work that he had al-ready done

and it kept him busy for another five years. It was only in 1816 now that he

passed on the twice done translation to England to be published in the joint

name of Leyden and him-self under the title Memoirs of Babur. A little time

before he had done that like Leyden five years earlier, he too received the Babur

Nama from Elphinstone but, possibly because he was not well-versed in Turki or

felt too tired to begin the translation, already done twice by him, for the

third time, made no use of the Turki manuscript. The Memoirs of Babur in Leyden

and Erskine's name finally published in 1826 were consequently rightly looked

upon by the indologists all over Europe as a translation of a translation of

Babur's memoirs.

In

the early years of the nineteenth century when the British interest in the

Mughals and their history was acquiring depth, a translation of the Waquit-i-Baburi,

was started by Dr Leyden. He seems to have liked the work and did lot of

jottings from Waquit-i-Baburi when Elphinstone arrived at Calcutta and sent him

the Babur Nama which he had purchased at Peshawar in 1810. The Babur Nãmã in

Turkish slackened Leyden's enthusiasm for the work that he had been doing and

he left the translation of Waquit-i-Baburi only partially done before his death

in 1811. What Leyden had left half done was completed by Erskine. Perhaps

without knowing that Leyden was engaged in the translation of Waquit-i-Baburi,

Erskine had also been busy translating it but just as he was thinking of giving

final touches to his translation, he received all the jottings and papers of

Leyden passed on to him after the latter's death in Java in 1811. The arrival

of Leyden papers forced Erskine to revise the work that he had al-ready done

and it kept him busy for another five years. It was only in 1816 now that he

passed on the twice done translation to England to be published in the joint

name of Leyden and him-self under the title Memoirs of Babur. A little time

before he had done that like Leyden five years earlier, he too received the Babur

Nama from Elphinstone but, possibly because he was not well-versed in Turki or

felt too tired to begin the translation, already done twice by him, for the

third time, made no use of the Turki manuscript. The Memoirs of Babur in Leyden

and Erskine's name finally published in 1826 were consequently rightly looked

upon by the indologists all over Europe as a translation of a translation of

Babur's memoirs.

The

Memoirs of Babur was looked upon as a valuable contribution to understanding

Babur. Its extracts were translated and published in German by A. Kaiser in

1828 as Denkwurd-ingkeiton des Zahir-uddin Muhammad Babur. In 1844, R. M.

Galdeff not only based his The Life of Babur on Leyden and Erskine's Memoirs of

Babur but further showed the importance in which he held the latter work by

publishing An Abridgement of the Memoirs, a work which was a summary of Leyden

and Erskine's work published eighteen years earlier.

The

Memoirs of Babur was looked upon as a valuable contribution to understanding

Babur. Its extracts were translated and published in German by A. Kaiser in

1828 as Denkwurd-ingkeiton des Zahir-uddin Muhammad Babur. In 1844, R. M.

Galdeff not only based his The Life of Babur on Leyden and Erskine's Memoirs of

Babur but further showed the importance in which he held the latter work by

publishing An Abridgement of the Memoirs, a work which was a summary of Leyden

and Erskine's work published eighteen years earlier.

It

was inevitable that the more the Leyden and Erskine's work was read, the

greater should be the demand for the original Turki Babur Nama and some

translation in a European language done directly from it. This demand was

mistakenly believed to have been satisfied by De Courteille who published in

1871 Les Memoirs de Biz-bur in French. De Courteille had done his translation

from Illminski's edited version of one Kehr's Turki transcript of the Babur Nama

lying at Petersberg but without knowing that Kehr's copy was not made from any

Babur Nama but an original work in Turki by one Timur-pulad, presented to one

of the members of the Russian Government in pursuance of the policy of Peter

the Great to improve Russian relations with the numerous Khanates in Central

Asia. When the mission returned to Petersberg, the member of the mission who

had received Timur-pulad's manuscript passed it on to Petersberg Library in the

Foreign Office. There it was noticed by one Kehr, a teacher in the School of

Oriental Studies at Petersberg. Kehr transcribed it as also translated it into

Latin. Because he had put the two side by side, Kehr's transcript begun to attract

more scholars than Timur-pulad's. In 1857 Illminski made Kehr's transcript as

the basis for preparing an indexed volume of what he believed was the Turkish Babur

Nama. What had been brought out by De Courteille was a French translation of

Illminski work minus the latter's edited remarks. And, since, as subsequently

discovered, Timur-pulad's work was not Babur Nama in Turki but at the best a

retranslation in Turki of the Persian translation of that done by Erskine four

decades earlier.

It

was left to Mrs. A. S. Beveridge to do the translation into English from a

genuine copy Turki Babur Nama. What made it possible for her to do that was

firstly the discovery of a genuine Turki copy of the Babur Nama in Hyderabad

and secondly her success in not only procuring it for herself for some time but

also have a number of fascimiles made of it by the E. J. Wilkinson Gibb Trust.

These fascimiles enabled Mrs. Beveridge to prove to scholars that the Hyderabad

Babur Nama surpassed both in volume and quality, all other Babur Nama. She

wrote a series of articles in the Journal of Royal Asiatic Society between 1900

and 1908 and finally came out with its English translation in 1926. It is this

translation which I have utilized in explaining the contents of paintings.

It

was left to Mrs. A. S. Beveridge to do the translation into English from a

genuine copy Turki Babur Nama. What made it possible for her to do that was

firstly the discovery of a genuine Turki copy of the Babur Nama in Hyderabad

and secondly her success in not only procuring it for herself for some time but

also have a number of fascimiles made of it by the E. J. Wilkinson Gibb Trust.

These fascimiles enabled Mrs. Beveridge to prove to scholars that the Hyderabad

Babur Nama surpassed both in volume and quality, all other Babur Nama. She

wrote a series of articles in the Journal of Royal Asiatic Society between 1900

and 1908 and finally came out with its English translation in 1926. It is this

translation which I have utilized in explaining the contents of paintings.

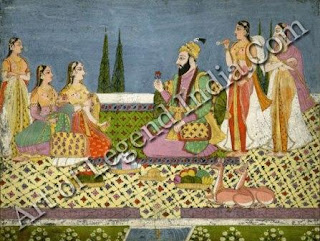

"Babur's

Memoirs form one of the best and most faithful pieces of autobiography

extant" wrote Dowson. "They are entirely superior to the hypocritical

revelations of Timur, and the pompous declarations of Jahangir not inferior in

any respect to the Expeditions of Xenophon, and rank but little below the

commentaries of Caesar." He further wrote "These Memoirs are the best

Memorial of the life and reign of the frank and jovial conqueror; they are ever

fresh and will long continue to be read with interest and pleasure."

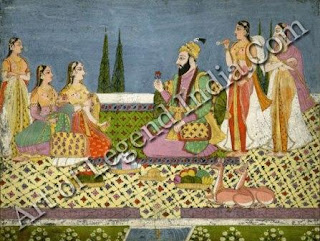

As a picture of the life of an Eastern

sovereign in court and camp, the book stands unrivalled among Oriental

autobiographies. "It is almost the only specimen of real history in

Asia... In Babur Nama the figures, dresses, habits, and tastes, of each

individual introduced are described with such minuteness and reality that we

seem to live among them, and to know their persons as well as we do their

characters. His descriptions of the countries visited, their scenery, climate,

productions, and works of art are more full and accurate than will, perhaps, be

found in equal space in any modern traveller."

As a picture of the life of an Eastern

sovereign in court and camp, the book stands unrivalled among Oriental

autobiographies. "It is almost the only specimen of real history in

Asia... In Babur Nama the figures, dresses, habits, and tastes, of each

individual introduced are described with such minuteness and reality that we

seem to live among them, and to know their persons as well as we do their

characters. His descriptions of the countries visited, their scenery, climate,

productions, and works of art are more full and accurate than will, perhaps, be

found in equal space in any modern traveller."

"His

Memoirs are no rough soldier's diary, full of marches and counter-marches;...

they contain the personal impressions and acute reflections of a cultivated man

of the world, well read in Eastern literature, a close and curious observer,

quick in perception, a discerning judge of persons, and a devoted lover of

nature.. .The utter frankness of self-revelation, the unconscious portraiture

of all his virtues and follies; his obvious truthfulness and fine sense of

humour give the Memoirs an authority which is equal to their charm."

It is

in truthful narration of events of his personal life that the value of the

Babur Nama lies. Like most adolescents Babur also passed through a homosexual

phase. He thus describes his love for a boy. "At this time there happened

to be a lad belonging to the camp-bazaar, named Baburi. There was an odd sort

of coincidence in our names. Sometimes it happened that Baburi came to visit

me; when, from shame and modesty, I found myself unable to look him direct in

the face. How then is it to be supposed that I could amuse him with

conversation or a disclosure of my passion? From intoxication and confusion of

mind I was unable to thank him for his visit; it is not therefore to be

imagined that I had power to reproach him with his departure. I had not even

self-command enough to receive him with the common forms of politeness. One day

while this affection and attachment lasted, I was by chance passing through a

narrow lane with only a few attendants, when, of a sudden, I met Baburi face to

face. Such was the impression produced on me by this encounter that I almost

fell to pieces. I had not the power to meet his eyes, or to articulate a single

word. With great confusion and shame I passed on and left him, remembering the

verses of Muhammad Salih:

It is

in truthful narration of events of his personal life that the value of the

Babur Nama lies. Like most adolescents Babur also passed through a homosexual

phase. He thus describes his love for a boy. "At this time there happened

to be a lad belonging to the camp-bazaar, named Baburi. There was an odd sort

of coincidence in our names. Sometimes it happened that Baburi came to visit

me; when, from shame and modesty, I found myself unable to look him direct in

the face. How then is it to be supposed that I could amuse him with

conversation or a disclosure of my passion? From intoxication and confusion of

mind I was unable to thank him for his visit; it is not therefore to be

imagined that I had power to reproach him with his departure. I had not even

self-command enough to receive him with the common forms of politeness. One day

while this affection and attachment lasted, I was by chance passing through a

narrow lane with only a few attendants, when, of a sudden, I met Baburi face to

face. Such was the impression produced on me by this encounter that I almost

fell to pieces. I had not the power to meet his eyes, or to articulate a single

word. With great confusion and shame I passed on and left him, remembering the

verses of Muhammad Salih:

"I

am abashed whenever T see my love;

My

companions look to me, and I look another way."

"The

verses were wonderfully suited to my situation. From the violence of my passion

and the effervescence of youth and madness, I used to stroll bare-headed and

barefoot through lane and street, garden and orchard, neglecting the attentions

due to friend and stranger; and the respect due to myself and others."

"The

verses were wonderfully suited to my situation. From the violence of my passion

and the effervescence of youth and madness, I used to stroll bare-headed and

barefoot through lane and street, garden and orchard, neglecting the attentions

due to friend and stranger; and the respect due to myself and others."

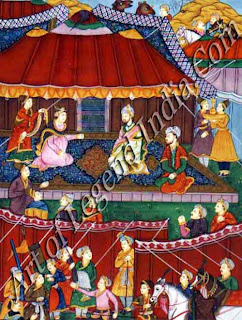

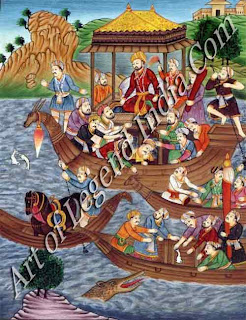

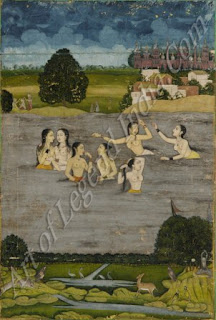

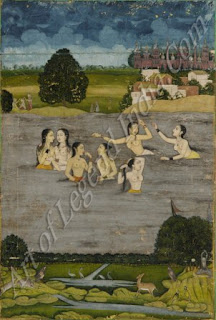

"Babur's

Memoirs reveal the founder of the Mughal rule in India as a constant and jovial

toper who had many a drinking party which were as important to him as his

bottles or negotiations. When we see him move with perfect ease and familiarity

among his company in these drinking parties we forget the prince in the man;

and start sharing the temptations that generally led Babur to those excesses a

shady wood, a hill with a fine prospect, or of a boat floating down a river;

and enjoy the amusements with which they are accompanied, extemporary verses,

recitations in Turki and Persian, with sometimes a song, and often a contest of

repartee.

"On

closing the Memoirs, we have in our possession a Babur who is more real than

political record would make him. We have a Babur who, after many many trials of

a long life, retains the same kind and affectionate heart, and the same easy

and sociable temper with which he had set out on his career and in whom the

possession of power and grandeur had neither blunted the delicacy of his taste,

nor diminished the sensibility to the enjoyment of nature and

imagination."

"On

closing the Memoirs, we have in our possession a Babur who is more real than

political record would make him. We have a Babur who, after many many trials of

a long life, retains the same kind and affectionate heart, and the same easy

and sociable temper with which he had set out on his career and in whom the

possession of power and grandeur had neither blunted the delicacy of his taste,

nor diminished the sensibility to the enjoyment of nature and

imagination."

To

Lane-Poole "Babur's Memoirs are no rough soldier's chronicles of marches,

'Saps, wines, blinds, zabions, palisades, revelings, half-moons and such trumpery';

they contain the personal impressions and acute reflections of a cultivated man

of the world, well read in Eastern literature, a close and curious observer,

quick in preception, discerning judge of men who was well able to express his

thoughts and observations in clear and vigorous language."

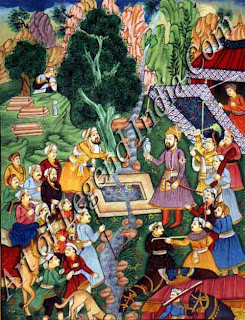

Apart

from its value as a source book of history, the importance of the Babur Nama

lies in the fact that it is the first book on Natural History of India. Babur

had keen sense of observation and he describes the physical features of the

country, its people, animals, birds, and vegetation with precision and brevity.

The value of some of the illustrations of the Babur Nama lies in the fact that

these are the first natural history paintings in India.

Writer – M.S. Randhawa

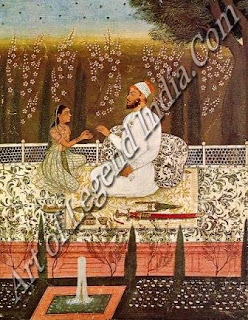

Babur won back the lost

territory from Jahangir who was supported by Ahmad Tambal when he defeated them

at Khuban in 1499. During this year he was married to Ayisha-Sultan Begam. She

did not attract him much and he mentions that out of modesty and bashfulness,

he used to see her only occasionally. In fact, his indifference to his wife was

due to the fact that he was infatuated with a youth named Baburi.

Babur won back the lost

territory from Jahangir who was supported by Ahmad Tambal when he defeated them

at Khuban in 1499. During this year he was married to Ayisha-Sultan Begam. She

did not attract him much and he mentions that out of modesty and bashfulness,

he used to see her only occasionally. In fact, his indifference to his wife was

due to the fact that he was infatuated with a youth named Baburi.  When in 1504 everything

appeared to have been lost, Babur with his three hundred and odd followers

crossed the Hindu Kush in a snow storm, stumbled into Kabul and made him-self

the master of a principality named after that city. Thus began the second phase

of his career. For the next twenty-two years, he was the king of Kabul which

roughly corresponded to the modern Afghanistan and included Badakshan. From

1504 to 1513, with Kabul as his base, Babur again tried to conquer Samarkand.

This ambition was fulfilled almost absolutely in October 1511 when he entered

that city "in the midst of such pomp and splendour as no one has ever

heard of before or ever since." Babur's dominions now reached their widest

extent: from Tashkent and Sairam on the borders of the deserts of Tartary, to

Kabul and Ghazni and the Indian frontier. It included within its boundaries

Samarkand, Bokhara, Hissar, Kunduz and Farghana. But this glory was as

shortlived as it was great. Uzbeg chiefs from whom Babur had snatched Samarkand

in October 1511 returned to attack the city in June 1512 and inflicted a

crushing defeat on Babur. Babur was forced to flee from one part of his

dominions to another. He lost everywhere and finally returned to Kabul early in

1513.

When in 1504 everything

appeared to have been lost, Babur with his three hundred and odd followers

crossed the Hindu Kush in a snow storm, stumbled into Kabul and made him-self

the master of a principality named after that city. Thus began the second phase

of his career. For the next twenty-two years, he was the king of Kabul which

roughly corresponded to the modern Afghanistan and included Badakshan. From

1504 to 1513, with Kabul as his base, Babur again tried to conquer Samarkand.

This ambition was fulfilled almost absolutely in October 1511 when he entered

that city "in the midst of such pomp and splendour as no one has ever

heard of before or ever since." Babur's dominions now reached their widest

extent: from Tashkent and Sairam on the borders of the deserts of Tartary, to

Kabul and Ghazni and the Indian frontier. It included within its boundaries

Samarkand, Bokhara, Hissar, Kunduz and Farghana. But this glory was as

shortlived as it was great. Uzbeg chiefs from whom Babur had snatched Samarkand

in October 1511 returned to attack the city in June 1512 and inflicted a

crushing defeat on Babur. Babur was forced to flee from one part of his

dominions to another. He lost everywhere and finally returned to Kabul early in

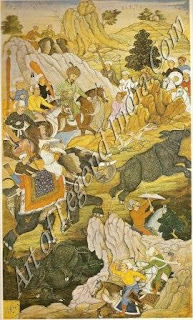

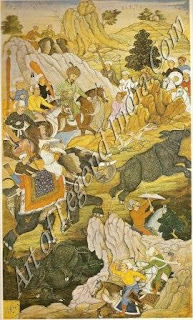

1513.  The First Battle of Panipat

began the last phase of Babur's life. It is well known in all its details to

the students of Indian history and may be briefly told. Babur states, "I

placed my foot in the stirrup of resolution, and my hand on the reins of

confidence in God, and marched against Sultan Ibrahim, the son of Sultan

Sikandar, the son of Sultan Bahlol Lodi Afghan, in whose possession the throne

of Delhi and the dominions of Hindustan at that time were; whose army in the

field was said to amount to a hundred thousand men, and who, including those of

his Amirs, had nearly a thousand elephants." For the first time in the

history of India artillery was used in warfare. Ustad Kuli Khan was the master

gunner of Babur. Indian elephants fled in terror on hearing the sound of artillery,

trampling Ibrahim's soldiers. By mid-day the battle was over. Ibrahim Lodi, lay

dead with 30,000 of his soldiers.

The First Battle of Panipat

began the last phase of Babur's life. It is well known in all its details to

the students of Indian history and may be briefly told. Babur states, "I

placed my foot in the stirrup of resolution, and my hand on the reins of

confidence in God, and marched against Sultan Ibrahim, the son of Sultan

Sikandar, the son of Sultan Bahlol Lodi Afghan, in whose possession the throne

of Delhi and the dominions of Hindustan at that time were; whose army in the

field was said to amount to a hundred thousand men, and who, including those of

his Amirs, had nearly a thousand elephants." For the first time in the

history of India artillery was used in warfare. Ustad Kuli Khan was the master

gunner of Babur. Indian elephants fled in terror on hearing the sound of artillery,

trampling Ibrahim's soldiers. By mid-day the battle was over. Ibrahim Lodi, lay

dead with 30,000 of his soldiers.