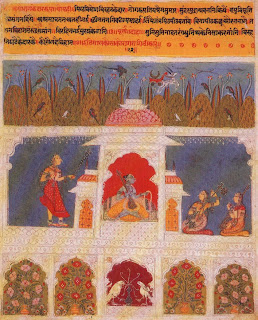

A.) This

painting is identified and described by the text in its upper panel as

representing Kedar Ragini, who is described as a love-torn, emaciated woman

wearing earrings, smeared with ashes as an ascetic, and playing a vina. The

ragini, a wife of Hindola Raga, is an early night melody characterized by

tenderness and believed to possess magical healing properties. In the

Rajasthani tradition Kedar Ragini is portrayed as a night scene with an ascetic

either playing or holding a vina or listening to a musician playing the

instrument. Surprisingly, the ascetic in this illustration is shown holding a

tambura rather "than a vina, while both instruments are being played by

two female musicians. In the sky above the trees an antelope pulls a celestial

chariot bearing a crescent moon, a symbol of Siva, the arch-ascetic of Indian

culture.

A.) This

painting is identified and described by the text in its upper panel as

representing Kedar Ragini, who is described as a love-torn, emaciated woman

wearing earrings, smeared with ashes as an ascetic, and playing a vina. The

ragini, a wife of Hindola Raga, is an early night melody characterized by

tenderness and believed to possess magical healing properties. In the

Rajasthani tradition Kedar Ragini is portrayed as a night scene with an ascetic

either playing or holding a vina or listening to a musician playing the

instrument. Surprisingly, the ascetic in this illustration is shown holding a

tambura rather "than a vina, while both instruments are being played by

two female musicians. In the sky above the trees an antelope pulls a celestial

chariot bearing a crescent moon, a symbol of Siva, the arch-ascetic of Indian

culture.

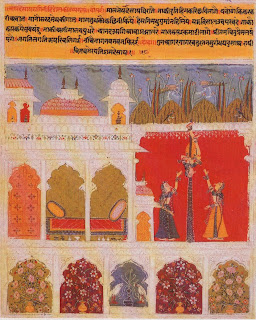

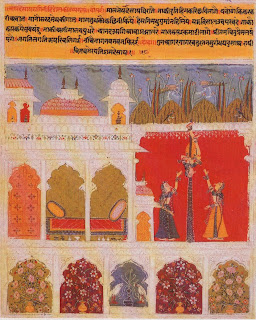

The presence of two paintings from the

same series in the Green collection provides an opportunity for viewers to

study the stylistic and compositional relationships between illustrations of

different ragas/raginis within a given Ragamala set. The present comparison is

especially instructive, for the careful observer will discern that the two

paintings, although clearly from the same series, were in fact painted by two

different artists. The major comparable features of the two include the

visually dominant expanses of white architecture and the division of the

paintings into four registers, composed of a row of niches with flowering

plants and parrots along the bottom, the figures and palatial setting in the

middle, the lines of trees in the penultimate register, and the lengthy poetic

passages, written in the same hand, in the yellow panel at the top.

Closer scrutiny of the two paintings,

however, reveals innumerable minute differences in detail. The treatment of the

pink lotus petals covering the surface of the architectural domes differs

considerably between the two: the dome of painting A has petals radiating

outward in a lively arrangement, but those of painting a lie in stiff

horizontal rows. The detailing in ink of the architecture, intended to represent

carved marble forms, is much finer and more complex in painting A than in B.

The vegetal and floral forms are related but differ in botanical structure and

array, with those of painting A generally more boldly portrayed. Figures and

animals are more supple and naturalistic in painting A. Given these variances

in detail and execution, painting A seems more accomplished than B and, by

extension, so was its painter. For other paintings from this series, see Pal

1978, pp. 114-15, no. 34 (Panchama Ragini); Pal 1981, p. 58, no. 47 (Kanhra

Ragini); and Sotheby's 1996, lot 186 (Malkos Raga). An additional unpublished

illustration of Mcgha-Mallar Raga from this series is in the Los Angeles County

Museum of Art.

A.) This

painting is identified and described by the text in its upper panel as

representing Kedar Ragini, who is described as a love-torn, emaciated woman

wearing earrings, smeared with ashes as an ascetic, and playing a vina. The

ragini, a wife of Hindola Raga, is an early night melody characterized by

tenderness and believed to possess magical healing properties. In the

Rajasthani tradition Kedar Ragini is portrayed as a night scene with an ascetic

either playing or holding a vina or listening to a musician playing the

instrument. Surprisingly, the ascetic in this illustration is shown holding a

tambura rather "than a vina, while both instruments are being played by

two female musicians. In the sky above the trees an antelope pulls a celestial

chariot bearing a crescent moon, a symbol of Siva, the arch-ascetic of Indian

culture.

A.) This

painting is identified and described by the text in its upper panel as

representing Kedar Ragini, who is described as a love-torn, emaciated woman

wearing earrings, smeared with ashes as an ascetic, and playing a vina. The

ragini, a wife of Hindola Raga, is an early night melody characterized by

tenderness and believed to possess magical healing properties. In the

Rajasthani tradition Kedar Ragini is portrayed as a night scene with an ascetic

either playing or holding a vina or listening to a musician playing the

instrument. Surprisingly, the ascetic in this illustration is shown holding a

tambura rather "than a vina, while both instruments are being played by

two female musicians. In the sky above the trees an antelope pulls a celestial

chariot bearing a crescent moon, a symbol of Siva, the arch-ascetic of Indian

culture.

B.)

Here the text in the upper panel identities the heroine as Desakhya

Ragini, a wife of Sri Raga, and describes her as a lovely woman wearing a sari

in Marathi fashion and performing an acrobatic movement on the upright pillar.

Desakhya Ragini is a late morning melody stressing the heroic sentiment.

Depictions of the ragini in the Rajasthani tradition feature a group of

acrobats performing feats of strength and coordination. Occasionally, as shown

here, women athletes are shown in place of their male counterparts in order to

reconcile the traditionally male quality of physical prowess with the feminine

gender of the melody.

Writer

Name:- Pratapaditya Pal

Punyaki Ragini

On the reverse of this painting are

inscribed in the Takri and Devanagari scripts, respectively, Punyaki Ragini and

Purvi Ragini. Analysis of the painting's iconography resolves the disparity and

corroborates the former identification. Both inscriptions label it correctly as

the wife of Bhairava Raga, number 4. Punyaki Ragini is a wife of Bhairava Raga

according to the Kshemakarna system, in which the melody is compared to the

.sound of rushing water. The term punya means the earning of religious merit

through charity. Consequently, as Indian religious ceremonies often involve the

pouring of consecrated water over a holy man's hands, representations of

Punyaki Ragini frequently portray the ablution of a mendicant's hands by the

lady of a house or palace.

This illustration of Punyaki Ragini

differs in that the lady is shown giving alms in the form of coins to a Saiva

mendicant rather than pouring water over his hands. Nevertheless, the

underlying rationale is the same, as it is still a meritorious act that is

being stressed in the painting. Indeed, other iconographic variations are

known, including the offering to the mendicant of a piece of jewelry or even a

sheaf of barley.

Ragamalas were a particularly popular

subject in Bilaspur painting between 1650 and 1780, a period coinciding with

the political and cultural zenith of the court. At least twenty-one Ragamala

sets were produced by the workshops of Bilaspur. Out of these sets, two other

representations of Punyaki Ragini are known to have survived: one from about

1690-95 and the other from about 1750. The three examples differ somewhat in

composition and expression, with the example of about 1690-95 and the present

painting being the closest in style. A number of Bilaspur stylistic features

are common to these two paintings, including a long spiraling lock of hair in

place of a sideburn for the mendicants, somewhat short figures, substantial

depictions of brickwork, and a distinctive, sultry palette.

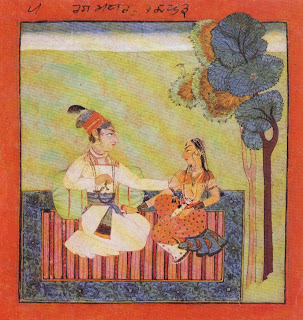

Harsha Ragaputra

In the upper border are rather indistinct

Takri and Devanagari inscriptions that both identify the painting as Harsha

Ragaputra, a son of Bhairava Raga. Kshemakarna's classification likens the

melody to the sound of running water and pictures the hero as an impetuous,

fair-skinned adolescent wearing a blue garment and a pearl necklace. The name

Harsha means rapture, especially that of a sexual nature. Pahari paintings of

the melody apparently take their inspiration from the description of the

personified hero and the lustful connotations of the name. They typically

portray the young hero seated or standing with a woman, usually in a bedchamber.

Often the couple are shown enjoying betel nut.

In the upper border are rather indistinct

Takri and Devanagari inscriptions that both identify the painting as Harsha

Ragaputra, a son of Bhairava Raga. Kshemakarna's classification likens the

melody to the sound of running water and pictures the hero as an impetuous,

fair-skinned adolescent wearing a blue garment and a pearl necklace. The name

Harsha means rapture, especially that of a sexual nature. Pahari paintings of

the melody apparently take their inspiration from the description of the

personified hero and the lustful connotations of the name. They typically

portray the young hero seated or standing with a woman, usually in a bedchamber.

Often the couple are shown enjoying betel nut.

This representation of Harsha Ragaputra

generally accords with the above iconographic description. A hero and heroine

are seated in a pavilion bedchamber. He wears a long strand of pearls and

rubies over his shoulder and a blue-striped purple garment, thus basically

agreeing with his prescribed adornment and garb. In place of sharing betel-nut

delicacies, however, the couple is shown gesticulating dramatically, and each

figure inexplicably holds a handkerchief. Another unusual feature of this

painting and the series to which it belongs, common to "only a few early

Pahari ragamalas", is that within the set the colors of the borders and

the backgrounds are coordinated for each raga's family. Hence, for this series

of the Bhairava family the borders are yellow and within them the backgrounds

are flaming orange.

This painting is from an important

Basohli series known generally as the Tandan Ragamala after the name of the

author who first published it. The set once belonged to the family of the

former court astrologer of Basohli. With sixty-five extant folios, it is the

most extensive of the early Pahari Ragamalas known to have survived. The

paintings were executed during the reign of Dhiraj Pal, who was a scholar and

patron of the arts. It has been dated to about 1700 by Tandan and to about

1707-15 by Khandalavala, either of which would place it in the middle of the

four other known Basohli Ragamalas ranging in date from about 1675 to about

1720. Stylistically, the present painting exhibits a number of characteristic

Basohli motifs and features. The most significant of these are the brilliant

palette, the distinctive elongated facial types with sloped foreheads, the

single tall cypress tree, the presence of small sections of iridescent beetle

thorax casing used to imitate emeralds, and the distinctive bejeweled golden

pendant worn by the hero, which is found only in Basohli portraits.

Madhu Ragaputra

The Takri inscription in the border above

this painting states it to be Madhu Ragaputra, a son of Bhairava Raga.

According to Kshemakarna, whose verse 20 describes the personification of the

melody, the protagonist is a handsome and knowledgeable man dressed in red

garments. In contrast, however, most Pahari representations of the melody,

including the present example, show a hero fondling his beloved's breasts.

Alternatively, the couple are depicted as drinking, with or without-a female

attendant.

This Chamba painting of about 1715 exhibits

strong stylistic influence from contemporary Basohli works. Figural and facial

types are similar, and coloration schemes of deep intense hues and

monochromatic backgrounds are analogous. In contrast, in contemporary Chamba

painting figures are generally somewhat less stylized, drapery and fauna

conventions differ, the palette is generally more subdued, and small sections

of beetle thorax casing arc never used for decoration as they are in the

Basohli tradition. The Ragamala set of which this painting was once a part

originally belonged to the Chamba royal family. It is now in the Bhuri Singh

Museum of Chamba except for some twelve dispersed pages. At least three other

Ragamala sets, all later than that of the present work, were also painted by

the Chamba ateliers.

Writer

Name:- Pratapaditya Pal