Demons

Corrupt Vedas

Demons

Corrupt Vedas

In Kali-yuga, the final quarter of the

world-cycle, the asuras stole the Vedas and used their mystical secrets to

become powerful beings. Mantras and yagnas were subverted for material gain,

their spiritual aims disregarded.

The

sapta rishis, ancient keepers of wisdom, went to Vishnu and complained

"Nobody understands the Vedas anymore. Corrupted by the demons, they fail

to direct man towards the divine. Save the texts before ignorance heralds the

day of doom."

Mayamoha Deludes Asuras

Vishnu

went to the kingdom of demons taking the form of a wily sage called Mayamoha,

the deluder, with Garuda accompanying him as a monk.

Clean

shaven, dressed in clothes of bark, with a begging bowl in hand, Mayamoha sat

amongst the asuras denouncing the Vedas. "Don't waste your time with these

high philosophies and complex rituals. They are nothing but superstitions. You

don't need them to be powerful."

With

clever arguments Mayamoha convinced the demons to abandon the Vedic way. They

stopped chanting mantras and performing yagnas. They threw the holy texts out

of their land and became heretics. The rishis recovered the Vedas and began

restoring them to their former glory.

The Divine Teacher

Meanwhile,

on earth, the distortion of the Vedas by the demons had caused confusion

mankind had lost touch with the divine. Life lacked direction. There was

suffering everywhere.

Meanwhile,

on earth, the distortion of the Vedas by the demons had caused confusion

mankind had lost touch with the divine. Life lacked direction. There was

suffering everywhere.

To

fight this ignorance with knowledge, Vishnu descended upon earth as the

enlightened teacher. Incarnating as Nara and Narayana, Kapila, Narada, Vyasa,

Datta, Rishabha and Buddha, the lord taught man the true nature of the cosmos.

He explained the mysteries of life and showed many ways to attain salvation.

Those

who lived by his words found themselves in the paradise of Vaikuntha, attuned

to the blissful rhythms of the cosmos. The rest, like demons, suffered the

pangs of existence.

Tapas of Nara-Narayana

On

the snowy peaks of the Himalayas, at Badrika, Nara-Narayana, two inseparable

sages, performed terrible austerities, tapas. Nobody knew what they sought.

"Maybe

they seek power," said the demon-king, Dambhodabhava. He sent hundreds of

soldiers to attack them. The sages refused to tight. Instead, they hurled

blades of grass which turned into fiery missiles killing everyone who dared

disturb their serenity.

The

god-king Indra sent hundreds of nymphs to seduce them. The sages remained

unmoved. "We can create them ourselves." So saying Nara and Narayana

rubbed their thighs and brought forth a voluptuous nymph called Urvashi, more

alluring than all of Indra's apsaras put together.

"What

do you want?" asked the gods and demons, unable to fathom the reason for

their tapas.

"We

seek the ultimate goal of existence realization and union with the divine

spirit. Power and pleasure are merely temporal delights that will wither away

someday," said Nara-Narayana.

Kapila and Jnana-yoga

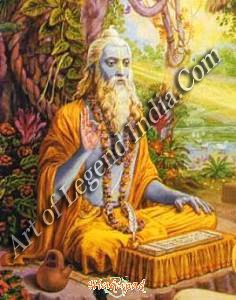

Kardama

renounced worldly life soon after his son Kapila , was horn. A time came when

Kapila decided to follow in his father's footsteps.

'Why

did I lose my husband? Why am I losing my son?" wondered Devahuti,

Kapila's mother, unable to come to terms with the separation.

Said

Kapila, "Nothing is permanent in the material world. All that you see,

smell, hear, touch or taste are material things, products of prakriti. They are

transitory pleasures here one moment, gone the next. If you want something

permanent, you must look beyond the material reality and get in touch with the

spiritual reality of the cosmos, the immutable purusha."

Kapila

went on to explain the structure of the world. He enumerated the two principles

which govern life eternal nil and transitory substance.

Kapila

went on to explain the structure of the world. He enumerated the two principles

which govern life eternal nil and transitory substance.

This

Santkhya philosophy became the corner-stone of nysticism and the foundation of

intellectual introspection - Jnana-yoga.

Narada and Bhakti-yoga

Even

after performing a hundred thousand yagnas, King Prachinabarhis was not happy. "What

have I done wrong? why am I not content? Why do I experience no bliss?" he

wondered.

The

sage Narada, lute in hand, came forward to solve the king's problem. "With

your rituals you are trying to control the world around you and make it work in

your 'our. But let me show you what you have really achieved."

Narada

pointed to a vast field covered with the carcasses cattle sacrificed in his

many rituals.

“Your

rites and rituals will never influence the workings he world. But for killing

these innocent beasts you will e to someday pay a terrible price."

Narada

continued, "The desire to manipulate events in one's favour is

unproductive because Vishnu, the supreme being, loves all creatures equally he

does not discriminate or favour anyone. Accept his divine intentions humbly

live life accordingly. Look at every event good or as the lord's gift, prasada,

an opportunity to discover the divine. Only then will you realise his benign

and live a life of joy."

Thos

did Narada direct the king Prachinabarhis to the path of devotion called

bhakti-yoga that leads straight to heart of Vishnu.

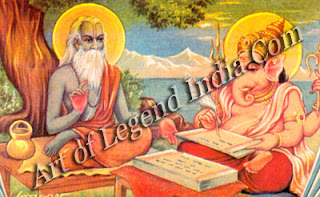

Veda Vyasa and Karma-yoga

The

sage Parashara fell in love with a fisherwoman called Satyavati as she ferried

him across the river Ganga. She gave birth to his son Krishna-Dwaipayana, so

called because of his dark complexion and because he was born on an island in

the middle of the river.

Satyavati's

son painstakingly compiled the Vedas, which had been lost to the world, with

Ganesha, the lord of wisdom, serving as his scribe. His work made him famous in

the three worlds as Veda Vyasa compiler of the books of knowledge.

Krishna-Dwaipayana

also wrote down the Adi Purana and the Itihasa, the book of myths and legends,

through which he propogated the doctrine of duty, karma-yoga.

Said

he, "Man must act according to dharma because dharma ensures harmony

between the self and the world around. Actions motivated by desire unravel the

cosmic fabric they also generate emotions that trap one within the material

world. Nishkama karma, selfless action focussed on duty not reward, enables one

to attain salvation without having to renounce the world."

The

followers of Vyasa became the first bards who revealed truth through tales of

gods, king and sages.

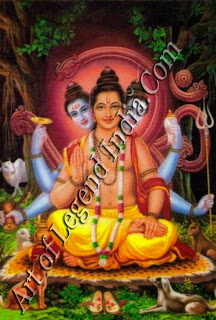

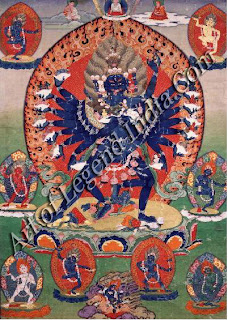

Dattatreya, the Mystic

Anasuya,

the wife of sage Atri, was renowned for her virtue. To test her, Vishnu arrived

at her doorstep disguised as a sage and asked her to feed him unclothed.

Anasuya, bound by the rules of hospitality, agreed to the strange request. But

such was the power of her chastity that when she brought the food, Vishnu

turned into an infant whom Anasuya fed as a mother, her virtue uncompromised.

When Vishnu recovered his original form, he blessed Anasuya, "You will

bear a son who will be the embodiment of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva."

Thus

was born Datta, the son of Anasuya. He was also known as Dattatreya after his

father,

the sage Atri.

Datta

observed Nature carefully the elements, the sun and the moon, birds and

animals, men and women and gained an insight into the nature of the world.

Inspired, he went on to compose the Avadhuta Gita the song of the recluse that

explains the doctrine of detachment, vairagya.

Through

various occult sciences like Tantra and mystical disciplines like Yoga,

Dattatreya taught mankind the means to yoke oneself to the way of the cosmos.

His students called him the fountainhead of all knowledge, the supreme teacher,

Adinatha.

He

wandered around the world as a mendicant with his cow, Bhoodevi herself, and

four dogs, embodiments of the Vedas. Said Dattatreya, "You can either

remain ignorant and abuse Nature or you can learn from her and realise

divinity."

Rishabha, the Ford-finder

Meru,

wife of the noble king Nabhi of Ayodhya, dreamt of a mighty bull as she gave

birth to her son. The prince was therefore named Rishabha bull amongst men.

Rishabha

ruled his kingdom wisely, teaching man seventy-two vocational skills and women

sixty-four domestic arts.

He

had many children. His daughter Brahmi invented the script called Brahmi. His

son Bharata was a great king of India; after him the land continued to be known

as Bharata-varsha, the kingdom of Bharata.

When

he had fulfilled his duties as a householder and king, Rishabha renounced

worldly life. He crowned Bharata as his successor and went into the wilderness

to live a life of austere contemplation.

Seated

on Mount Kailasa, Rishabha reiterated the Jain philosophy, one of the oldest

doctrines of liberation that enables man to break the fetters of karma and

transcend samsara. Rishabha thus created a bridge out of the wheel of existence

and became tirthankara the ford-finder.

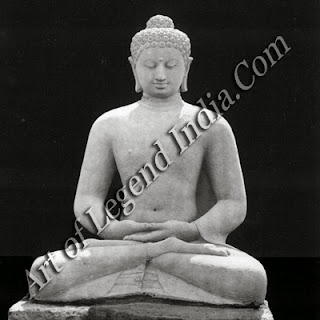

Buddha, the Enlightened One

Gautama,

the Sakya prince of Kapilavastu, grew up surrounded by royal comforts adored by

his loving mother. When he came of age, he married the beautiful princess

Yashodhara. Within the walls of his palace there was nothing but joy.

But

one day, as he rode through the city, he became aware of the suffering that

plagues the life of every man poverty, old age, disease and death.

He

witnessed innocent animals and birds being mercilessly slaughtered by priests

in elaborate ceremonies in the hope of relieving sorrow and ushering in joy.

In

his compassion, Gautama decided to find the reason behind suffering. "Once

I know what makes man unhappy, I will find a way to make him happy."

He

renounced his wife and child, his wealth and crown and lived a life of a

mendicant in the forest, fasting, meditating, talking to wise men, seeking a

solution to the misery of man.

He

sat under a pipal tree and refused to get up until he had found the answer. In

time he did. He realised desire was the root of all pain.

As

Buddha, the enlightened one, Gautama concluded that to be free of desire one

had to alter one's attitude towards the world and seek answers within oneself,

through contemplation and restraint. He propogated a disciplined way of life

based on compassion known as Buddhism the path of the enlightened.

Writer Name: Decdutt Pattanaik

Read More:

Demons

Corrupt Vedas

Demons

Corrupt Vedas Meanwhile,

on earth, the distortion of the Vedas by the demons had caused confusion

mankind had lost touch with the divine. Life lacked direction. There was

suffering everywhere.

Meanwhile,

on earth, the distortion of the Vedas by the demons had caused confusion

mankind had lost touch with the divine. Life lacked direction. There was

suffering everywhere.  Kapila

went on to explain the structure of the world. He enumerated the two principles

which govern life eternal nil and transitory substance.

Kapila

went on to explain the structure of the world. He enumerated the two principles

which govern life eternal nil and transitory substance.

.jpg)