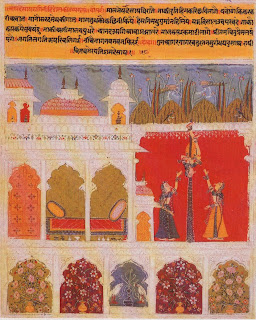

A.) This

painting is identified and described by the text in its upper panel as

representing Kedar Ragini, who is described as a love-torn, emaciated woman

wearing earrings, smeared with ashes as an ascetic, and playing a vina. The

ragini, a wife of Hindola Raga, is an early night melody characterized by

tenderness and believed to possess magical healing properties. In the

Rajasthani tradition Kedar Ragini is portrayed as a night scene with an ascetic

either playing or holding a vina or listening to a musician playing the

instrument. Surprisingly, the ascetic in this illustration is shown holding a

tambura rather "than a vina, while both instruments are being played by

two female musicians. In the sky above the trees an antelope pulls a celestial

chariot bearing a crescent moon, a symbol of Siva, the arch-ascetic of Indian

culture.

A.) This

painting is identified and described by the text in its upper panel as

representing Kedar Ragini, who is described as a love-torn, emaciated woman

wearing earrings, smeared with ashes as an ascetic, and playing a vina. The

ragini, a wife of Hindola Raga, is an early night melody characterized by

tenderness and believed to possess magical healing properties. In the

Rajasthani tradition Kedar Ragini is portrayed as a night scene with an ascetic

either playing or holding a vina or listening to a musician playing the

instrument. Surprisingly, the ascetic in this illustration is shown holding a

tambura rather "than a vina, while both instruments are being played by

two female musicians. In the sky above the trees an antelope pulls a celestial

chariot bearing a crescent moon, a symbol of Siva, the arch-ascetic of Indian

culture.

The presence of two paintings from the

same series in the Green collection provides an opportunity for viewers to

study the stylistic and compositional relationships between illustrations of

different ragas/raginis within a given Ragamala set. The present comparison is

especially instructive, for the careful observer will discern that the two

paintings, although clearly from the same series, were in fact painted by two

different artists. The major comparable features of the two include the

visually dominant expanses of white architecture and the division of the

paintings into four registers, composed of a row of niches with flowering

plants and parrots along the bottom, the figures and palatial setting in the

middle, the lines of trees in the penultimate register, and the lengthy poetic

passages, written in the same hand, in the yellow panel at the top.

Closer scrutiny of the two paintings,

however, reveals innumerable minute differences in detail. The treatment of the

pink lotus petals covering the surface of the architectural domes differs

considerably between the two: the dome of painting A has petals radiating

outward in a lively arrangement, but those of painting a lie in stiff

horizontal rows. The detailing in ink of the architecture, intended to represent

carved marble forms, is much finer and more complex in painting A than in B.

The vegetal and floral forms are related but differ in botanical structure and

array, with those of painting A generally more boldly portrayed. Figures and

animals are more supple and naturalistic in painting A. Given these variances

in detail and execution, painting A seems more accomplished than B and, by

extension, so was its painter. For other paintings from this series, see Pal

1978, pp. 114-15, no. 34 (Panchama Ragini); Pal 1981, p. 58, no. 47 (Kanhra

Ragini); and Sotheby's 1996, lot 186 (Malkos Raga). An additional unpublished

illustration of Mcgha-Mallar Raga from this series is in the Los Angeles County

Museum of Art.

A.) This

painting is identified and described by the text in its upper panel as

representing Kedar Ragini, who is described as a love-torn, emaciated woman

wearing earrings, smeared with ashes as an ascetic, and playing a vina. The

ragini, a wife of Hindola Raga, is an early night melody characterized by

tenderness and believed to possess magical healing properties. In the

Rajasthani tradition Kedar Ragini is portrayed as a night scene with an ascetic

either playing or holding a vina or listening to a musician playing the

instrument. Surprisingly, the ascetic in this illustration is shown holding a

tambura rather "than a vina, while both instruments are being played by

two female musicians. In the sky above the trees an antelope pulls a celestial

chariot bearing a crescent moon, a symbol of Siva, the arch-ascetic of Indian

culture.

A.) This

painting is identified and described by the text in its upper panel as

representing Kedar Ragini, who is described as a love-torn, emaciated woman

wearing earrings, smeared with ashes as an ascetic, and playing a vina. The

ragini, a wife of Hindola Raga, is an early night melody characterized by

tenderness and believed to possess magical healing properties. In the

Rajasthani tradition Kedar Ragini is portrayed as a night scene with an ascetic

either playing or holding a vina or listening to a musician playing the

instrument. Surprisingly, the ascetic in this illustration is shown holding a

tambura rather "than a vina, while both instruments are being played by

two female musicians. In the sky above the trees an antelope pulls a celestial

chariot bearing a crescent moon, a symbol of Siva, the arch-ascetic of Indian

culture.

B.)

Here the text in the upper panel identities the heroine as Desakhya

Ragini, a wife of Sri Raga, and describes her as a lovely woman wearing a sari

in Marathi fashion and performing an acrobatic movement on the upright pillar.

Desakhya Ragini is a late morning melody stressing the heroic sentiment.

Depictions of the ragini in the Rajasthani tradition feature a group of

acrobats performing feats of strength and coordination. Occasionally, as shown

here, women athletes are shown in place of their male counterparts in order to

reconcile the traditionally male quality of physical prowess with the feminine

gender of the melody.

Writer

Name:- Pratapaditya Pal

Punyaki Ragini

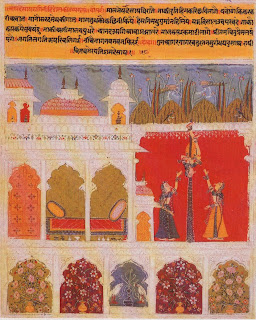

On the reverse of this painting are

inscribed in the Takri and Devanagari scripts, respectively, Punyaki Ragini and

Purvi Ragini. Analysis of the painting's iconography resolves the disparity and

corroborates the former identification. Both inscriptions label it correctly as

the wife of Bhairava Raga, number 4. Punyaki Ragini is a wife of Bhairava Raga

according to the Kshemakarna system, in which the melody is compared to the

.sound of rushing water. The term punya means the earning of religious merit

through charity. Consequently, as Indian religious ceremonies often involve the

pouring of consecrated water over a holy man's hands, representations of

Punyaki Ragini frequently portray the ablution of a mendicant's hands by the

lady of a house or palace.

This illustration of Punyaki Ragini

differs in that the lady is shown giving alms in the form of coins to a Saiva

mendicant rather than pouring water over his hands. Nevertheless, the

underlying rationale is the same, as it is still a meritorious act that is

being stressed in the painting. Indeed, other iconographic variations are

known, including the offering to the mendicant of a piece of jewelry or even a

sheaf of barley.

Ragamalas were a particularly popular

subject in Bilaspur painting between 1650 and 1780, a period coinciding with

the political and cultural zenith of the court. At least twenty-one Ragamala

sets were produced by the workshops of Bilaspur. Out of these sets, two other

representations of Punyaki Ragini are known to have survived: one from about

1690-95 and the other from about 1750. The three examples differ somewhat in

composition and expression, with the example of about 1690-95 and the present

painting being the closest in style. A number of Bilaspur stylistic features

are common to these two paintings, including a long spiraling lock of hair in

place of a sideburn for the mendicants, somewhat short figures, substantial

depictions of brickwork, and a distinctive, sultry palette.

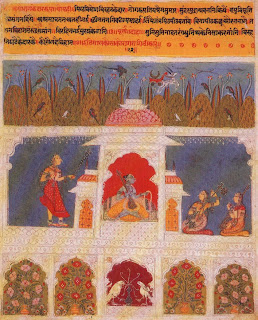

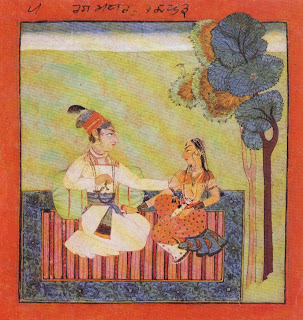

Harsha Ragaputra

In the upper border are rather indistinct

Takri and Devanagari inscriptions that both identify the painting as Harsha

Ragaputra, a son of Bhairava Raga. Kshemakarna's classification likens the

melody to the sound of running water and pictures the hero as an impetuous,

fair-skinned adolescent wearing a blue garment and a pearl necklace. The name

Harsha means rapture, especially that of a sexual nature. Pahari paintings of

the melody apparently take their inspiration from the description of the

personified hero and the lustful connotations of the name. They typically

portray the young hero seated or standing with a woman, usually in a bedchamber.

Often the couple are shown enjoying betel nut.

In the upper border are rather indistinct

Takri and Devanagari inscriptions that both identify the painting as Harsha

Ragaputra, a son of Bhairava Raga. Kshemakarna's classification likens the

melody to the sound of running water and pictures the hero as an impetuous,

fair-skinned adolescent wearing a blue garment and a pearl necklace. The name

Harsha means rapture, especially that of a sexual nature. Pahari paintings of

the melody apparently take their inspiration from the description of the

personified hero and the lustful connotations of the name. They typically

portray the young hero seated or standing with a woman, usually in a bedchamber.

Often the couple are shown enjoying betel nut.

This representation of Harsha Ragaputra

generally accords with the above iconographic description. A hero and heroine

are seated in a pavilion bedchamber. He wears a long strand of pearls and

rubies over his shoulder and a blue-striped purple garment, thus basically

agreeing with his prescribed adornment and garb. In place of sharing betel-nut

delicacies, however, the couple is shown gesticulating dramatically, and each

figure inexplicably holds a handkerchief. Another unusual feature of this

painting and the series to which it belongs, common to "only a few early

Pahari ragamalas", is that within the set the colors of the borders and

the backgrounds are coordinated for each raga's family. Hence, for this series

of the Bhairava family the borders are yellow and within them the backgrounds

are flaming orange.

This painting is from an important

Basohli series known generally as the Tandan Ragamala after the name of the

author who first published it. The set once belonged to the family of the

former court astrologer of Basohli. With sixty-five extant folios, it is the

most extensive of the early Pahari Ragamalas known to have survived. The

paintings were executed during the reign of Dhiraj Pal, who was a scholar and

patron of the arts. It has been dated to about 1700 by Tandan and to about

1707-15 by Khandalavala, either of which would place it in the middle of the

four other known Basohli Ragamalas ranging in date from about 1675 to about

1720. Stylistically, the present painting exhibits a number of characteristic

Basohli motifs and features. The most significant of these are the brilliant

palette, the distinctive elongated facial types with sloped foreheads, the

single tall cypress tree, the presence of small sections of iridescent beetle

thorax casing used to imitate emeralds, and the distinctive bejeweled golden

pendant worn by the hero, which is found only in Basohli portraits.

Madhu Ragaputra

The Takri inscription in the border above

this painting states it to be Madhu Ragaputra, a son of Bhairava Raga.

According to Kshemakarna, whose verse 20 describes the personification of the

melody, the protagonist is a handsome and knowledgeable man dressed in red

garments. In contrast, however, most Pahari representations of the melody,

including the present example, show a hero fondling his beloved's breasts.

Alternatively, the couple are depicted as drinking, with or without-a female

attendant.

This Chamba painting of about 1715 exhibits

strong stylistic influence from contemporary Basohli works. Figural and facial

types are similar, and coloration schemes of deep intense hues and

monochromatic backgrounds are analogous. In contrast, in contemporary Chamba

painting figures are generally somewhat less stylized, drapery and fauna

conventions differ, the palette is generally more subdued, and small sections

of beetle thorax casing arc never used for decoration as they are in the

Basohli tradition. The Ragamala set of which this painting was once a part

originally belonged to the Chamba royal family. It is now in the Bhuri Singh

Museum of Chamba except for some twelve dispersed pages. At least three other

Ragamala sets, all later than that of the present work, were also painted by

the Chamba ateliers.

Writer

Name:- Pratapaditya Pal

Lanka Restored

The battle was over. Ravana's huge body

lay sprawled on the ground, covered in blood and surrounded by the gruesome

aftermath of war, charred and mutilated remains covering the field as far as

the eye could see. At his side knelt Vibhisana, with Rama standing behind him.

'O great hero,' mourned Vibhisana, 'why

are you lying here, my brother, rather than on the sumptuous bed that you are

used to? You did not take my advice. Now that you have fallen, the city of

Lanka and all her people are reduced to ruin.'

'Do not lament,' said Rama. 'He

terrorized the universe, even Indra himself. Sooner or later he had to die, and

he chose to die the glorious death of a. warrior.'

'He was generous to his friends and

ruthless to his enemies,' said Vibhisana, 'and religious according to his own

tradition he chanted the Vedic hymns and kept a sacred fire burning in his

home.'

'Now you must consider how to perform his

funeral rites,' said Rama.

'He was my older brother, but he was also

my enemy and lost my respect. He was cruel and deceitful, and violated other

mens' wives. I do not know if he deserves a proper cremation,' confessed

Vibhisana.

'He was immoral and untruthful, after the

nature of a rakshasa,' replied Rama, 'but he was gifted and brave. Cremate him

with respect and let enmity end with death.'

Then came Ravana's wives, braving the

horrors of the battlefield to be at their husband's side. They threw themselves

around him, sobbing and stroking his head.

'If only you had heeded Vibhisana and

returned Sita to Rama,' they cried, 'none of this would have happened and we

would be spared the curse of becoming widows.'

How could you, who conquered heaven, be

overcome by a man wandering in the forest?' spoke Mandodari, Ravana's chief

queen. 'The only explanation is that Vishnu, the Great Spirit and eternal

sustainer of the worlds, took human form as Rama to finish your life. Sita was

the cause of your downfall. The moment you touched her your end was assured.

The only reason the gods did not strike you down was because they feared you,

but your actions still brought the fruits they deserved. One who does good

gains happiness and the sinner reaps misery; no one can escape this law. ,

'You were advised by me, Maricha,

Vibhisana, your brother Kumbhakarna, and my father, but you ignored us all.'

Mandodari wept on Ravana's breast and her fellow wives tried to console her.

Meanwhile Rama sent Vibhisana into the

ruined city of Lanka to make the funeral arrangements and perform the closing

rites for Ravana's sacred fire. Soon he returned with the sacred embers,

articles of worship and firewood for the pyre carried by rakshasa priests and

attendants. They decorated Ravana's linen shroud with flowers and carried his

body in procession to the beach, preceded by the sacred fires and followed by

weeping rakshasa women.

Vibhisana ignited the pyre while the

remaining family members threw rice grains into the flames. Vedic hymns were

intoned as the mourners looked on in silence.

When all was finished they returned to

the city. His anger exhausted, Rama put away his weapons. A deep joy welled in

his heart and his gentle demeanor returned.

Sita's Ordeal by Fire

With Ravana out of the way, Rama's

thoughts turned to Sita. He called Hanuman and asked him to take her the news

of Ravana's death. He came to the ashok grove and found her as before, unwashed

and uncared for with tears in her eyes, seated on the ground beneath the tree

guarded by demon women. He stood respectfully at a distance to deliver his

message.

With Ravana out of the way, Rama's

thoughts turned to Sita. He called Hanuman and asked him to take her the news

of Ravana's death. He came to the ashok grove and found her as before, unwashed

and uncared for with tears in her eyes, seated on the ground beneath the tree

guarded by demon women. He stood respectfully at a distance to deliver his

message.

'Lord Rama is safe and well, and has

killed Ravana. He sends you this message: "After many sleepless months I

have bridged the sea and fulfilled my vow to win you back. You now need have no

fear as you are in the hands of Vibhisana, the new king of Lanka, who will soon

come to see you". Sita was speechless with joy to hear this news and

waited for more. But Hanuman remained silent.

'This news is more valuable than all the

gold and jewels in the universe,' she laughed, 'and you have delivered it in

such sweet words. I cannot repay you enough.'

'If you will permit me, I can deal

swiftly with these cruel rakshasa women,' offered Hanuman, eager to be of

service. 'They have so mistreated you. Let me kill them now with my bare

hands.'

'You must not be angry with them,'

reproved Sita. 'They have only done what they were ordered to do. Whatever I

have suffered is due to my own sins, not to them. When others mistreat me, I

will not mistreat them in return. I will show compassion to all, even if they

are unrepentant murderers.' Hanuman checked himself.

'Then have you any message for your

husband?' he asked.

'Tell him I long to see him!'

'You shall see him this very day.' With

these words Hanuman swiftly flew back to Rama with Sita's message, and urged

him to go to her at once to end her misery. Rama sighed deeply in an effort to

hold back his tears. After a moment he turned to Vibhisana.

'Go quickly and fetch Sita. Before

bringing her here see that she is bathed, dressed in fresh clothes, and adorned

as befits a queen.'

Sita waited in the grove, expecting Rama,

but instead she saw the ladies of Vibhisana's household who came to bring her

to his house, where Vibhisana told her to bathe and dress in preparation for

meeting Rama.

'I want to see my husband now, as I am,'

she protested, but Vibhisana prevailed on her to do Rama's bidding. The ladies

helped her bathe and combed out her tangled hair, dressed her in fine clothes

and ornaments and placed her inside a palanquin, covered so that no one could

see her. Soon she was brought by a company of rakshasas to Rama's presence.'

During this time Rama remained deep in

thought, considering how to welcome Sita. The strict codes of the royal house

of Iksvaku demanded that a princess violated by an . enemy must be rejected by

her husband. Sita had been Ravana's prisoner for eleven months. Who knows what

that immoral demon might have subjected her to? Rama trusted Sita completely,

but he was determined that she must be publicly exonerated from any

impropriety. He knew what he must do.

What happened next is painful to recount.

Monkeys and rakshasas crowded forward on

all sides, anxious for a glimpse of the fabled princess. Vibhisana, hoping to

protect Sita from the public, told her to wait in her palanquin, but Rama

wanted her brought out in the open.

'These are my people and they want to see

her,' he spoke sternly. 'At a time like this there are no secrets, even for

royal princesses. Bring her here in front of everyone.'

Vibhisana was uncomfortable with this

order, but dared not contradict him. Sita had to suffer the indignity of

walking in front of thousands of curious eyes on her way to Rama. She reached

him and stood at a respectful distance, her head bowed, and shyly looked into

his face. As she gazed into his eyes her discomfort was forgotten for the

moment and she glowed with happiness.

'I have won you back according to my

vow,' announced Rama. 'The insult against me has been avenged, and its

perpetrator repaid for his terrible offence against you. I am once more my own

master. All this has been done with the help of Hanuman, Sugriva and Vibhisana,

to whom I am indebted.'

Rama spoke without emotion, but his voice

sounded strange as it rang out across the crowd. His heart bled for Sita, but

he must not show it. She looked upon her lord, with tears falling down her

cheeks, and dreaded what he might say next.

'I have redeemed my honour and won you

back,' he went on, 'but I did not do this for your sake, fair princess, I did

it for the sake of my honour and for the good name of the royal house of

Iksvaku. Your honour is not so easy to redeem, since you have lived in the

house of a demon who has embraced you in his arms and made you the object of

his lust. You are "so desirable, Ravana could not have resisted you for

long. I therefore relinquish my attachment to you. You are free to go wherever

you please. If you like you can go with Lakshmana, or Bharata, or even Sugriva

or the rakshasa Vibhisana. Do as you please.'

A shocked silence fell over the assembly.

Sita tried to rake in what she had just heard. She had never in her life

received a cross word from her husband. Now he had condemned her in public with

these awful words. For her this was worse than death. She bowed her head in

shame before this crowd of strangers and cried uncontrollably as Rama waited in

stern silence for her response. After a little while she wiped her eyes and

stood straight, her face pale and her voice trembling.

'You speak hurtful words, my lord, as if

I were a common prostitute, but I am not what you take me for. I am daughter of

the earth, who was seized against my will by force. If you were to reject me it

would have been better if you had told me through Hanuman when he first came.

Then I would have put an end to my life and saved you the trouble of coming

here to kill Ravana, endangering the lives of all these innocent people. You

forget that when I was a child you took my hand and promised me your protection

and that I have served you faithfully ever since. My heart has always remained

fixed on you, but now you of all people do not trust me. What am I to do?'

Sita's voice broke with emotion. She turned to speak to Lakshmana.

'I have no desire to live when I have

been falsely accused and publicly rejected by my husband. Death is my only course.

Prepare a pyre for me I will enter the flames.'

Stunned at this request, Lakshmana looked

at his brother. Rama nodded his assent. No one dared to contradict him, whose

anger seemed capable of destroying the universe. Lakshmana mechanically went about

his brother's bidding, and before long a funeral pyre had been built and set

alight. The fire began to crackle. Sita circled around Rama in respect and

proceeded towards the pyre. Standing before the blazing flames she called in a

loud voice:

'May all the gods be my witness. I have

never been unfaithful to Rama in thought, word or deed. If the Fire god knows

me to be innocent, let him protect me from these flames.' Then she walked into

the fire. As she entered the flames the crowd gasped in horror. The flames

leapt high and parted over her head as she stepped among them, swallowing her

golden form. For a moment she could be seen standing in the midst of the flames

like a dazzling flame of gold, then she was lost to sight. Women screamed and

fainted. A great cry, strange and terrible to hear, went up from all the

monkeys; bears and rakshasas present. Rama sat immobile like one who has lost

his life, and tears flooded his eyes.

As the incarnation of Vishnu, Rama had

accomplished all the gods had asked of him. But the gods heard Sita's cry for

help and were troubled at her ordeal. It was time for them to intervene. The

creator Brahma, Shiva the destroyer, Indra the king of heaven, and others all

boarded their aerial cars and flew down to earth, where they appeared shining

in front of Rama and spoke to him.

'Have you forgotten who you are and who

Sita is? You are the source of creation, the beginning, middle and end of all

that exists. And yet you treat Sita as an ordinary fallen woman.'

'I am a human being. My name is Rama, son

of Dasaratha, and Sita is my human wife. Who do you say I am?'

'You are the supreme Lord Vishnu and Sita

is your eternal consort, the goddess Lakshmi,' declared Brahma. 'You are

Krishna. You are the Cosmic Person, the source of all, creator of Indra and the

gods, and the support of the entire creation. No one knows your origin or who

you are, yet you know all living beings. You are worshipped in the form of the

Vedic hymns and the mystic syllable om, and night and day are the opening and

closing of your eyes.

'At our request you took human form to

put an end to Ravana. Now you have accomplished this, and your devotees who

praise you will be blessed for evermore.'

Then the Fire god, Agni, rose up out of

the flames of the funeral pyre bearing Sita in his arms. She was unharmed by

the fire and her clothes and ornaments, even the flowers decorating her hair,

were exactly as before. Agni brought her to Rama.

'Here is your wife Sita who is without

sin. She has never been unfaithful to you, in thought, word or deed. I command

you to treat her gently.'

'This ordeal for Sita was necessary,'

Rama explained, 'I had to absolve her from any blame and to preserve the good

name of the Iksvaku race. I know she has always been faithful, but I had to

prove her innocence. In truth I could not be separated from Sita any more than

the sun can part from its own rays. But I thank you and accept, without

reservation, your words of advice.' With these words, Sita and Rama were

re-united. Then there was a further surprise.

'You have rid the world of the curse' of

Ravana,' said Lord Shiva. 'Now you have one thing more to do before you return

to heaven. You must bring comfort to your mother and brothers and prosperity to

Ayodhya. Greet your deceased father, whom I have brought from heaven to see

you.'

Rama and Lakshmana bowed in wonder as

Dasaratha descended in their midst, his celestial form shining. Reaching the

ground he took them in his arms.

'I am so pleased for you, dear boy,' he

said to Rama, 'and at what you have achieved. You have set my mind at rest,

which has long been haunted by Kaikeyi's words, and you have redeemed my soul.

I now recognize you to be the Supreme Person in the guise of my son. Now you

have completed fourteen years in exile, please return to Ayodhya and take up

the throne.'

Turning to Lakshmana, he said, 'Your

service to Rama and Sita has brought Rama success, the world happiness, and

will bring you its own reward. I am deeply pleased with you, my son.' Then he

spoke to Sita.

'My daughter, please forgive Rama, who

was inspired only by the highest motive. You have shown your purity and courage

by entering the flames, and you will be revered henceforth as unequalled among

chaste women.' With those words, Dasaratha ascended, to heaven. It now remained

for Indra to grant Rama one last wish.

'We are all pleased with your actions,

Rama, and would like to grant you a boon. What is your wish?'

Rama was unhesitating. 'May all these

monkeys and bears, who have sacrificed their lives for me, be brought back to

life and returned to their wives and families.'

'It shall be done,' declared Indra. Then

the monkeys and bears rose up, their limbs restored and their injuries healed,

as if from a long and peaceful sleep. 'You may return to your homes,'

pronounced the assembled gods. 'And Rama — be kind to the noble princess Sita.

Make haste to Ayodhya, where your brother Bharata awaits you.' Then they

boarded their golden aerial cars and departed for the heavens.

Homecoming

Vibhisana invited Rama to take his bath

and put on royal robes and ornaments.

'I cannot bathe until I have been reunited

with Bharata,' said Rama. 'For the last fourteen years he has lived as an

ascetic for my sake. Now I must hurry to him. If you would please me, help me

to get to Ayodhya as soon as possible.'

'That is easily done,' replied Vibhisana.

'The fabulous Puspaka airplane will fly you there by sunset. But first remain

here a while and let me entertain you and your army.'

'I would not refuse you, Vibhisana, after

you have done so much for me, but I long to see Bharata and my mother.'

Vibhisana summoned the airplane which

arrived instantly, gleaming with its golden domes. Rama took the shy Sita in

his arms and boarded the plane with Lakshmana.

'Settle peacefully in your kingdoms,' he

told Sugriva, Vibhisana and their ministers. 'You have both served me well. I

must return.' But they were not ready to part.

'Let us come to Ayodhya and see you

crowned,' they protested. 'Only then will we return to our homes.' Rama happily

agreed and invited them aboard with all their followers. Miraculously there was

enough room aboard the airplane for everyone. When all was ready, the Puspaka

ascended effortlessly into the sky amid great excitement. Rama took Sita to a

balcony and they looked down at the island of Lanka.

'See, princess, the city of Lanka and

outside it the bloody field of battle. Here, at Setubandha, is where we built

the bridge across the sea and I received the blessings of Lord Shiva. Now you

see Kiskindha, Sugriva's capital where I killed Vali.' As they approached

Kiskindha, Sita made a request.

'Let me invite the wives of the monkeys

to come with us to Ayodhya.' It was done. The airplane touched down and took

aboard thousands before proceeding on its way.

'Now see Mount Rishyamukha, where I spent

the rainy season in sorrow and where we first met Hanuman and Sugriva. And here

is that enchanting place where we lived in our cottage and where you were

carried away by Ravana, and over there is the place where the brave Jatayu

died. Here are the ashrams of Agastya, Sutikishna and Sarabanga, and here is

where you met the noble Anasuya, wife of Atri. Here is Chitrakoot, the most

beautiful of hills, where Bharata found us.'

They stopped overnight at Bharadvaja's

ashram and Rama sent Hanuman ahead with messages for Bharata. He was worried

that Bharata might resent having to give up the kingdom to his brother. He need

not have feared. Hanuman arrived at the village of Nandigram, outside Ayodhya,

and found Bharata living as Rama had lived during his exile, dressed in

deerskin, with Rama's wooden shoes occupying the central position in his court.

When he heard of Rama's return he jumped for joy and hugged Hanuman, showering

him with gifts.

The next morning Bharata led everyone out

to meet Rama, with Rama's sandals at the head of the procession. A great cry

went up when the people saw Lord Rama seated in the Puspaka airplane as it

slowly descended. Rama came forward and took Bharata in his arms. Bharata

hugged Lakshmana and greeted Sita, then he embraced one by one all the leading

monkeys. Rama tearfully clasped the feet of his mother and offered his respects

to the sage Vasistha. Bharata then placed his shoes back on his feet.

'I return to you your kingdom which I

have held in trust for you,' said Bharata with emotion. 'By your grace all has

flourished and my life is now fulfilled.' Again Rama hugged Bharata, while many

of the monkeys, and even Vibhisana, shed a tear.

Rama was placed in the hands of barbers

who shaved his beard and untangled his matted locks. Then he and Sita were

bathed and dressed in royal finery. Sumantra brought up Rama's royal chariot

and in grand procession entered Ayodhya, with Bharata at the reins and his

brothers fanning him. Sugriva and the monkeys were welcomed into the heart of

Ayodhya where Rama gave them the freedom of his royal palace and gardens.

For Rama's coronation, monkeys were sent

by Sugriva to collect water from the four seas, east, south, west and north,

and from five hundred rivers. Vasistha conducted the ceremony, bathing Rama

with the sacred waters and installing Sita and Rama on the throne. Rama

distributed gifts to all his people."

Sita looked kindly on Hanuman, unclasping

her pearl necklace. She hesitated, looking shyly at her husband. Rama

understood. 'Give it to the one who has pleased you best,' he said, and she

placed it around Hanuman's neck.

During Rama's rule there was no hunger,

crime or disease. People lived long, the earth was abundant, society prospered

and all were dedicated to truth. For his people, Rama was everything and he

ruled them for eleven thousand years.

Whoever daily hears this Ramayana,

composed in ancient times by Valmiki, is freed from all sins. Those who hear

without anger the tale of Rama's victory will overcome all difficulties and

attain long life, and those away from home will be re-united with their loved

ones. Rama is none other than the original Lord Vishnu, source of all the

worlds, and Lakshmana is his eternal support.

Epilogue

.JPG) For a month after Rama's coronation,

festivities and merry-making continued. When it was time for them to go, the

monkeys cried and stammered; it was a sad parting. Last of all came Hanuman.

For a month after Rama's coronation,

festivities and merry-making continued. When it was time for them to go, the

monkeys cried and stammered; it was a sad parting. Last of all came Hanuman.

'My Lord, please grant my request,'

submitted Hanuman. 'Let me always be devoted to you and no one else, and let me

live as long as your story is remembered on earth.'

Rama hugged Hanuman and granted his wish,

saying, 'Your fame and your life will last as long as My story is repeated,

which will be until the end of the world.'

After Rama's guests had gone he spent

many happy days roaming with Sita in the royal pleasure groves. In this way

nearly two years passed. One day Sita appeared more beautiful than usual, and

Rama knew that she was pregnant.

'My dearest Sita, you are going to have a

child. Is there anything you wish?'

'I would dearly like to visit the ashrams

across the Ganges, and stay one more night with those sages eating only roots

and fruits.'

'Please rest tonight and tomorrow I will

arrange it,' promised Rama.

That evening he sat as usual with his

friends and chanced to ask them for the gossip among the people of Ayodhya

concerning their king and queen.

'They praise you and your victory over

Ravana,' came the reply.

'Do they say nothing against me?' Rama

inquired. 'You may speak without fear.'

One of them admitted that men all over

his kingdom spoke ill of his relationship with Sita. They said that since Rama

had accepted Sita back after she had been touched by Ravana, they would now

have to tolerate unfaithfulness from their own wives, because whatever the king

does his subjects will follow. When he heard this Rama was astonished and

turned to his other friends.

Is this so?' he asked in dismay.

One by one they nodded, 'It is true, my

lord.' Dumbfounded and full of grief, Rama dismissed them and sat deep in

thought. After a while he sent for his three brothers. They arrived to find him

crying. They bowed and waited for him to speak.

'In times of trouble you three are my

life,' he began. 'Now I need your help and support more than ever.' He paused

while they waited anxiously.

I have just been informed that my Sita is

not approved by the people they think her unchaste. This is despite the trial I

subjected her to in Lanka, where the gods themselves testified to her purity. I

know her to be pure, yet dishonor, for a king, is worse than any other fault. I

would rather die than fail to uphold honour.

'Therefore my mind is made up. Sita has

told me she wants to visit the ashrams on the other side of the Ganges.

Lakshmana, tomorrow you must take her there and leave her in the care of the

sage Valmiki. Please don't try to dissuade me from this.' With a heavy heart,

Rama took leave of his brothers and spent the night in sorrow.

In the morning Lakshmana set off with

Sita in his chariot, driven by Sumantra, on the two-day journey to the Ganges.

On the way Sita noticed strange symptoms.

'How is it, Lakshmana, that my right eye

throbs and my limbs shiver? My heart beats faster as though I were distressed.

Is all well?'

'All is well, my lady,' Lakshmana said.

But when they reached the Ganges he sat down by the river and sobbed.

'Why are you crying, Lakshmana?' asked

Sita. `Do you miss Rama? Come, let us cross the Ganges now, and after one night

we will return to see him.'

Lakshmana checked his tears and together

they boarded a boat. Once they reached the other side and got out of the boat

Lakshmana broke down.

'My heart is pierced by an arrow. I have

been entrusted to carry out an awful deed for which I will be hated for ever. I

would rather die!'

Sita was alarmed. 'What is it, Lakshmana?

It seems you are not well, and neither was Rama when I said goodbye to him. Do

tell me what is wrong.'

'Rama has heard unpleasant rumours,'

Lakshmana stammered. 'It seems the people think you unchaste. In great pain he

has ordered me to leave you here at Valmiki's ashram, although he knows you to

be blameless. Valmiki was a close friend of our father and will care for you.

Please stay here peacefully and hold Rama always in your heart.

Sita fell unconscious on the ground.

'This body of mine was created only for

sorrow,' she wept. 'What sin have I com-mitted that I should be made to suffer

like this? If! were not bearing Rama's child I would drown myself in the

Ganges.

'Do as the king has ordered, Lakshmana,'

she went on. 'Leave me here. Please wish my mother’s well, and give this

message to Rama: "You know I am pure, and will always remain devoted to

you. To save you from dishonor I make this sacrifice. Please treat all your

citizens as you would your brothers, and bear yourself with honour, then these

false rumours will be disproved. You, my husband, are dearer to me than my

life." Now look at me one last time, Lakshmana, and depart.'

'I will not look at your beauty now,

lady, since all my life I have looked only on your feet,' said Lakshmana

through his tears. He bowed his head at her feet and boarded the boat. Without

looking back he urged the boatman on.

Sita remained crying by the riverside.

Her cries were heard by the young ascetics of Valmiki's ashram and they brought

the news to him. He gently brought her into his ashram, reassuring her that she

need have no fear. Lakshmana, from across the river, saw her taken in and

returned to Ayodhya.

Valmiki knew Sita was blameless and that

she carried Rama's child. He took her to the women ascetics who lived nearby as

his disciples, and instructed them to care for her as their own child. There

Sita lived in peace and bore twin sons named Kusa and Lava. In time, Valmiki

taught them his poem describing their father's deeds, Ramayana.

With help from Lakshmana, Rama learned to

live with his sorrow after the loss of Sita, and found consolation in caring

for his people. But he kept her always in his heart. Twelve years passed and

Ayodhya prospered. To ensure the continued well-being of the kingdom, Rama

decided to perform the exalted asvamedha ceremony, as had his father before his

birth. When all was ready, the sage Valmiki arrived with Kusa and Lava and told

them to recite Ramayana as he had taught them.

Kusa and Lava were asked to sing their

tale for the king, and all present noticed their striking resemblance to Rama.

After several days of recital the story revealed them to be the sons of Sita.

When Rama understood this his heart troubled him. He sent word to Valmiki

inviting him to bring Sita to Ayodhya, if she so agreed, to declare her

chastity and exonerate her name.

Valmiki gave his approval and brought

Sita to a great gathering in the presence of Rama. He stood in front of the

people and spoke.

'Your majesty, Sita has lived under my

care since you abandoned her. Now she has come to proclaim her honour. I,

Valmiki, who never spoke a lie, declare these twin sons of hers to be your sons

and Sita to be without sin.'

'Honorable sage,' said Rama, 'I have

always known that Sita is pure and I acknowledge these two boys as my sons. The

gods themselves vouched for Sita's purity. Nonetheless, the people did not

trust her, therefore I sent her away, although I knew her to be sinless. I beg

her forgiveness.'

Sita advanced into the middle of the

assembly. In full view of all, with her eyes cast downwards, she made a vow.

'If I have always been faithful to Rama,

in mind, word and deed, may Mother Earth embrace me. If I know only Rama as my

worshipful lord, let her take me now.'

At that moment the Earth goddess rose

from the earth on a beautiful throne. She took Sita in her arms and sat her on

the throne, then withdrew with her into the earth. Petals fell from the sky and

cries of adoration echoed from the gods.

Rama sank back in tears. He raged at the

earth to return Sita, threatening to break down her mountains and over flood

her surface. It was necessary for Brahma to appear before Rama and pacify him

by reminding him that, as Vishnu, he would be reunited with Sita in heaven.

Rama mastered his grief. He returned to

ruling his 4 kingdom and caring for his people. In time, he installed his sons

and his brother's sons as rulers. Eleven thousand years passed by.

One day a strange figure appeared at his

door. It was Death personified, sent with a message from Brahma. The message

said, 'You are the eternal Vishnu who sleeps on the causal ocean. In ancient

times I, the creator, was born from you. In order to kill Ravana, you entered

the world of humans and fixed your stay for eleven thousand years. That time is

now complete. Please return to protect the gods.'

Rama set off for the banks of the Sarayu

river, taking with him his brothers and all who were devoted to him. Ayodhya

was without a living soul. Only Hanuman, Vibhisana and Jambavan remained on

earth. Entering the waters of the Sarayu with his devoted followers, Rama left

this world and returned to his eternal realm, where his devotees eternally

serve the Lord of their hearts, forever reunited with his beloved Sita.

Writer

Name: Ranchor Prime

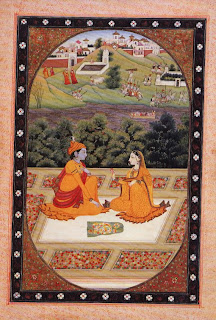

According to the text on its reverse (see

Appendix), this painting is an illustration from a Baramasa (The twelve months)

series of the month of Chaitra (March-April), which is the first month of the

traditional Indian calendar. The verses describe the splendor of the blossoming

spring landscape and the sexually exhilarating effect of the season on peacocks

and maidens. The painting depicts Krishna sitting on a garden terrace with

Radha, who is trying to persuade the blue-skinned lord to stay with her rather

than go traveling during the month. In the background of the painting are a

landscape) and a river that is rendered with fine, parallel lines reminiscent

of Western engraving techniques. There is also a town, temple tank, and walled

compound, as well as numerous inhabitants portrayed in an impressionistic

manner. A mid-nineteenth-century date for the painting is suggested by the

background features as well as the figural and clothing style of Krishna and

the distinctive zigzag hemline of Radha's garment (cf. Leach, p. 301, no. 129).

The Baramasa literature of medieval

northern India consists of various cycles of oral and written celebrations of

the seasonal varieties of the behavior and feelings of lovers over the course

of the twelve lunar months of the year. Verses devoted to the twelve months

survive from at least as far back as the twelfth century and were particularly

popular during the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries in Bengal, Gujarat,

and Rajasthan (Vaudeville). Ancient Sanskrit verses glorifying the seasons

exist, such as the Ritusamhara (Collection of the seasons) by the great poet

and playwright Kalidasa (c. 365-c. 455), but these are specifically concerned

with the traditional six Indian seasons of spring, summer, the rains, autumn,

winter, and the cool season rather than with the twelve months of the year. The

majority of Baramasa verses composed primarily of village women's folk songs or

literary poems written in the various regional vernacular languages emphasize

the pain of a young wife's separation from her beloved. Descriptions of the

different seasons are paired with diverse feelings of longing to evoke the

individual mood of each month. Greater emphasis is given to the four months of

the rainy season (June through September) than to the remainder of the year,

and a select grouping of songs and poems, the Caumasa (Four months), even

evolved to celebrate the especially emotive rainy season, which is

traditionally connected with the laments of lovers in separation.

Among the best known of the poetic

expressions of the Baramasa are those contained in the tenth chapter of the

Kavipriya (The poet's breviary), a work on rhetoric written in 1601 by

Kesavadas for his patron Indrajit Shah's favorite courtesan, Pravinaraye. The

Baramasa verses in the Kavipriya describe the monthly climates and activities

of Indian life and relate them to the joys and sorrows of lovers. It was these

poems by Kesavadas, rather than the village Baramasa folk songs, that were

favored and illustrated by Pahari painters.

Writer

Name: - Pratapaditya Pal

.JPG)

.JPG)